George Economou: Three More Poems from "Finishing Cavafy’s Unfinished" with a note on the process

CRIME

This was found among some poet’s papers.

It’s dated, but quite illegibly.

A one scarcely visible, next nine, next

one, the fourth number looks like a nine.

Stavros dealt out our shares in the loot.

The alpha youth in our gang,

smart, tough, and too beautiful for words.

The most capable, though except for me

(I was twenty) he was the youngest.

My guess is he wasn’t quite twenty-three.

Our haul was three thousand pounds.

He kept, as we convinced him was fair, half of it.

But now, at eleven at night, we were working on

putting him on the lam the next morning,

before the police found out about the burglary.

Not a lightweight heist, but grand larceny.

We were down in a cellar, safe-housed in a basement.

After we’d decided on the plan for his escape,

the other three left us, me and Stavros,

with the understanding they’d return at five.

There was a ripped up mattress on the floor.

Dead-tired, the two of us dropped. And with our shaky

feelings, and the extreme fatigue,

and with the anguish over his getaway

in the morning––I hardly realized, didn’t realize at all

that in these last hours together our love had come to its end.

(1927)

FOURSOME

Their way of making money was surely not aboveboard.

But they’re street-smart boys, the four of them, who’ve figured out

how to do their business steering clear of the police.

Apart from being smart, they’re super tough together.

Since two of them are joined by the bond of pleasure

so are the other two joined by the bond of pleasure.

They can dress to kill as is quite suitable

for such handsome boys, and the theater and bars,

and their snazzy car, and a trip now and then

to Cairo in the winter, they are missing nothing.

Their way of making money was surely not aboveboard,

with an occasional scare of getting cut up

or of doing time in jail. But look at how Love

has such power to take the dirty money they make

and fashion it anew into something blindingly pure.

That money none of them wants for himself or

for personal interests. None of them tallies it up

grossly or with greed. They never take note

if one brings in less or another more.

In common they hold their money, using it

to dress with style, to bankroll the outlay

that makes their lives elegant and well-suited

to such handsome boys, for helping out their friends,

and then, as is their way, just forget about it.

(1930)

ZENOBIA

Now that Zenobia’s become queen of numerous great lands,

now that she’s the wonder of the Anatolian world,

and now that even the Romans fear her,

why shouldn’t her greatness be fulfilled?

Why should she be pigeonholed as Woman/ Asian?

Two scholars well versed in history

will prepare her genealogy forthwith.

Look at how she’s clearly descended from the Lagids.

Look at how clearly from Macedonia her bloodline flows

into the stream of her noble Semitic spring: “Augusta” suits her well.

Clearly one day soon she’ll parade through Rome in wraps of gold.

(1930)

[a note to zenobia. Septimia Zenobia (Bat-Zabbai in Aramaic; al-Zabba in Arabic), who was born around 240 A. D. and died some time after 274, the “warrior queen” of the Roman colony of Palmyra (in present day Syria), was the second wife of King Septimus Odaenathus and succeeded him after his assassination in 267. Unusually ambitious, beautiful, courageous, and highly cultured (the rhetorician and critic Longinus lived in her court), and expert in creative biographic enhancements, she proclaimed herself “Augusta” and ruled from 268 to 272, conquering several Roman provinces, including Egypt and Anatolia, before she was subjugated by the emperor Aurelius (270––275). There are numerous accounts of what happened to her after her military losses, but the most accepted one is that Aurelius proved merciful and granted her a good Roman life in exile after she was displayed in golden chains (a star even in defeat?) at his triumph.]

on finishing cavafy. The three poems in this third and final installment from an ongoing project that will be published by Shearsman Books in the fall of 2015 as the first part of a work entitled Finishing Cavafy’s Unfinished & Selected Poems and Translations present two unusual features in a collaboration with Cavafy that I have previously described as un métissage de l’écriture, a trans-compositional approach in which the work of translator and poet have been combined in order to create a finished poem in English out of the variable complex elements in the unfinished drafts of their Greek originals. The making of the first two poems in this trio, “Crime” and “Foursome,” was basically carried out following the same process that directed the composition of most of the poems in this collection out of the drafts, variants, and marginal comments and corrections that portray the singular nature of each of Cavafy’s unfinished poems as diplomatically edited and reconstructed by Renata Lavagnini (Atele Poiemata, 1918-1932, Athens: Ikaros, 2006).

“Crime” and “Foursome”(provisionally entitled “A Company of Four” by its author) stand out among the “unfinished poems” but also among all the other poems––published, unpublished and rejected––because of the poet’s explicit and sympathetic treatment of their attractive young criminals. It is well-known that many of Cavafy’s poems explore the lives of poor young men, an interest he expressed in a note he wrote on June 29, 1908: “I am pleased and moved by the beauty of the masses, of poor young men. Servants, workers, petty clerks and shop attendants. It is the compensation, one imagines, for their deprivations” (Selected Prose Works, translated and edited by Peter Jeffreys, Ann Arbor, 2010, p. 136). Although at times these poems skirt the shadows of questionable and rough and tumble life-styles and occasionally even obliquely suggest some sort of illicit or criminal activity, none so openly represent, or actually celebrate as in “Foursome,” beautiful young mobsters as do these two poems. If in finishing them, I have at times resorted to idiomatic expressions unmistakably rooted in our own underworld culture, I have done so in response to the emotional force that pervades and impels these two extraordinary poems.

The unique demand of the third unfinished poem of this group, “Zenobia,” that I complete rather than merely finish it, was anticipated by a small distraction in Professor Lavagnini’s reconstruction of “Foursome” in which the tenth line lacks its second half, a defect Cavafy never allows in any of the numerous poems in which he uses this unusual, personal form of verse consisting of lines divided by caesura-like spaces into two metrically analogous parts. I have addressed the problem caused by this puzzling omission by shifting the phrase in the first half of the line to the second half and completing the line with the phrase “to Cairo in the winter” on the strength of Cavafy’s addition of it in one of the draft stages in the poem’s file. Further confirmation of the cogency of using this added phrase came when I read the final paragraph in Lavagnini’s commentary on this poem, which begins: “The trip to Cairo (added here at sheet 4, line 8) symbolizes an easy-going and carefree life,” and continues with an account of how Cavafy recalled that his father made frequent trips to Cairo (p. 288).

That Professor Lavagnini’s reconstruction of “Zenobia” comes to an abrupt stop mid-poem with two crosses, each of which, according to her editorial apparatus, represents two illegible letters, after the word “Macedonia” in Cavafy’s single sheet manuscript comes as no surprise considering the great vacillation with which this sole, somewhat inchoate, draft was written. After composing a brief note on Zenobia, my common practice for all of the historical figures mentioned in Cavafy’s Unfinished Poems, I proceeded to work towards a rendition of the customary “finished” version that has been the goal of every poem in this project. Then I suddenly understood that my commitment to Cavafy to “finish” every one of these poems meant in this anomalous case that I had to “complete” that fragmentary version, which I did unhesitatingly, with the moderate addition of two and a half italicized lines that proceed syntactically out of his text into an alluring ironic closing informed by several details from some of his favorite sources that I hope is worthy of the splendid Alexandrian. (G. E.)

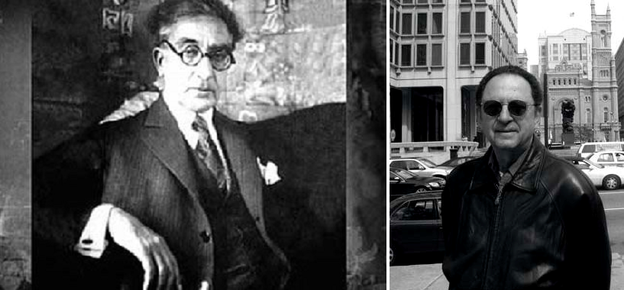

Photo of George Economou by Andrea Augé

Poems and poetics