Alejandra Pizarnik: From 'Uncollected Poems (1962–1972)'

Translation from Spanish & commentary by Cole Heinowitz

[The eight poems posted here are taken from the 17 typed manuscript pages Pizarnik brought to the home of the poet Perla Rotzait in 1971, less than a year before her death.]

1 […] ON SILENCE

…it’s all in some language I don’t know…

L. C. (Through the Looking-glass)

I feel the world’s pain like a foreign language.

Cecilia Meireles

They play the part “estranged”.

Michaux

… SOMEBODY killed SOMETHING.

L. Carroll (Through the Looking-glass)

I.

This little blue doll is my envoy in the world.

An orphan in the garden rain where a lilac-colored bird gobbles lilacs and

a rose-colored bird gobbles roses.

I’m frightened of the grey wolf lurking in the rain.

Whatever you see, whatever can be taken away, is unspeakable.

Words bolt all doors.

I remember rambling through the sycamores …

But I can’t stop the drama—gas fills the chambers of my little doll’s heart.

I lived the impossible, destroyed by the impossible.

Oh, the banality of my evil passions,

enslaved by ancient tenderness.

II.

No one paints in green.

Everything is orange.

If I am anything, I’m cruelty.

Colors streak the silent sky like rotting beasts. Then someone tries to write

a poem out of forms, colors, bitterness, lucidity (Hush, alejandra, you’ll frighten

the children…)

III.

The poem is space and it scars.

I am not like my little blue doll who still suckles the milk of birds.

Memory of your voice in the fatal morning guarded by a sun rebounding

in the eyes of turtles.

The light of sense goes out remembering your voice before this green

celestial mixture, this marriage of sea and sky.

And I prepare my death.

2 [untitled]

She wants to speak, but I know what she is. She believes love is death—even if everything devoid of love disgusts her. Since her love makes her innocent, why should she speak? Mistress of the Castle, her fingers play upon mirrors of pronouns.

With every word I write I remember the void that makes me write what I couldn’t if I let you in.

I stand by the poem. It takes me to the edge, far from the homes of the living. And when I finally disappear—where will I be?

No one understands. Everything I am waits for you and still I hunt the night of the poem. I think only of your body while I shape and reshape my poem’s body as if it were broken.

And no one understands me. I know that life and love must change. Such statements, coming from the mask over the animal I am, painfully suggest a kinship between words and shadows. And that’s where it comes from, this state of terror that negates humanity.

26/XI/69

3 NIGHT, THE POEM

If you find your true voice, bring it to the land of the dead. There is kindness in the ashes. And terror in non-identity. A little girl lost in a ruined house, this fortress of my poems.

I write with the blind malice of children pelting a madwoman, like a crow, with stones. No—I don’t write: I open a breach in the dusk so the dead can send messages through.

What is this job of writing? To steer by mirror-light in darkness. To imagine a place known only to me. To sing of distances, to hear the living notes of painted birds on Christmas trees.

My nakedness bathed you in light. You pressed against my body to drive away the great black frost of night.

My words demand the silence of a wasteland.

Some of them have hands that grip my heart the moment they’re written. Some words are doomed like lilacs in a storm. And some are like the precious dead—even if I still prefer to all of them the words for the doll of a sad little girl.

23/XI/69

4 [untitled]

Even if she saw me cry and clutched me to hear breast, I wouldn’t revive. True, I’d be able to look in her eyes like Van Gogh saw the sun and shattered it in sunflowers—Can “life” be spelled with two “i”s?

Dolls are so cruel. And why shouldn’t they be, when men and beasts and even stones are cruel? In the poem, dolls and other creatures of the night are exposed. Poem, this is night. Have you met the night?

Roses are red in her fiery insatiable hands.

I call night silence. Night emerges from death. Night emerges from life. All absence lives in the night.

Then, in the morning, I cried:

My darling night, my little one, teeming with villains.

My love, call me Sasha. I’m recasting the play as a purely interior tragedy. Everything is an interior.

feb. 1970

5 BLANK SLATE

cisterns in memory

rivers in memory

pools in memory

always water in memory

wind in memory

whispering in memory

6 WANTED: DEAD OR ALIVE

I forced myself

kicking and screaming

into language

7 ONLY SIGN

Please alejandra

open your eyes,

kindle the light

of birth.

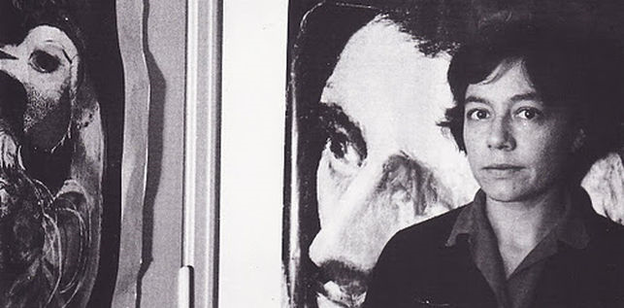

[COMMENTARY. Flora Alejandra Pizarnik (1936-1972) was born to Russian Jewish parents in an immigrant district of Buenos Aires. During her short life, spent mostly between Buenos Aires and Paris, Pizarnik produced an astonishingly powerful body of work, including poetry, short stories, paintings, drawings, translations, essays, and drama. From a young age, she discovered a deep affinity with poets who, as she would later write, exemplified Hölderlin’s claim that “poetry is a dangerous game,” sacrificing everything in order to “annul the distance society imposes between poetry and life.” She was particularly drawn to “the suffering of Baudelaire, the suicide of Nerval, the premature silence of Rimbaud, the mysterious and fleeting presence of Lautréamont,” and, perhaps most importantly, to the “unparalleled intensity” of Artaud’s “physical and moral suffering” (“The Incarnate Word,” 1965).

Like Artaud, Pizarnik understood poetry as an absolute demand, offering no concessions, forging its own terms, and requiring that life be lived entirely in its service. “Like every profoundly subversive act,” she wrote, “poetry avoids everything but its own freedom and its own truth.” In Pizarnik’s poetry, this radical sense of “freedom” and “truth” emerges through a total engagement with her central themes: silence, estrangement, childhood, and—most prominently—death. An orphan girl’s love for her little blue doll pumps death gas through the heart of her avatar. The garden of forgotten myth is a knife that rends the flesh. A grave opens its arms at dawn in the fusion of sea and sky. Every intimate word spoken feeds the void it burns to escape. Pizarnik’s poetry exists on the knife’s edge between intolerable, desolate cruelty and an equally intolerable human tenderness. From her historical essay on “The Bloody Countess,” Erzebet Bathory: “the absolute freedom of the human is horrible.” From a late interview with Martha Isabel Moia: the job of poetry is “to heal the fundamental wound,” to “rescue the abomination of human misery by embodying it.”

The uncollected poems presented here (written between 1969 and 1971) are drawn from a 17-page manuscript Pizarnik entrusted to the poet Perla Rotzait less than a year before her suicide.]

Poems and poetics