Norman Finkelstein and Tirzah Goldenberg

A poetic dialogue

[What follows is an attempt by two poets to create as linked dialogue a specifically “Jewish poetry” — more mystical and religious, as I read it, than sentimental. The excerpts (ten out of thirty-six poems) and the poets’ later reflections on intention and process are presented below without any attempt at further clarification. (j.r.)]

nights the woodcutter won’t sleep / the flutist alights in the treetops days / an eruv round the village the woodfolk make / wine underfoot the woodfolk make woodcuts / a fox afoot where curiouser minhagim have been made / barks past elder sycamore / sees

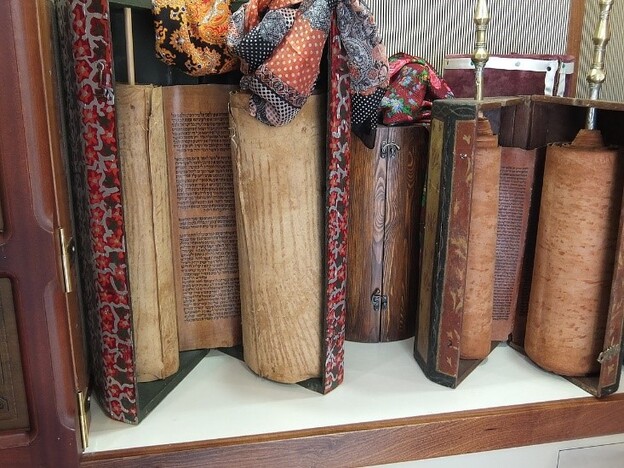

our singular dark furniture awake / rouses antique leathern threadbare bellows / furnishing unwonted flame / barks the route to write the annals / secretly, like the Tao / worded like the nigun isn’t, o / gently heating loophole of the blech / all rabbinic handicraft is symbol / all symbol’s handicraft / all’s golden threads in lions embroidered on dark curtains / the eruv’s up, secure / a fox afoot before the ark’s dark door / to Torah sing secure / all’s arc’s dark door to Torah

* * *

all’s arc’s dark door to Torah

arc-en-ciel, Ark of the Covenant,

ark we have all boarded whether

alone or in pairs. I have loved

the Torah more than God, but I

have loved the writing more than

the Torah, because the writing

is the ark, carried us full circle.

Carried on the wings of the fox,

the wings of the lion, curtains

like a cape, like a magic carpet.

This is called riding the wind

or writing the wind, this is

familiar, my familiar, cat or

mouse, the cat crying, the mouse

singing, here, where no birds sing.

* * *

singing, here, where no birds sing

sing birds in a wilderness once consonants

once vowels once familiars

wants the ayin and the aleph tolled

in the full throat of difference in the forge

where folk spoke fully anciently once aneni

(answer me) once ani (I)

regarded each other learnedly

et ratzon (at a favorable time)

now I not a moose

but a hoof print evidence

we kneel we bow

we bless the presence

the Ayin enwrapped in

a creek at this time

* * *

a creek at this time

of year may overflow

its banks. Flooded or so

I was taught, when feelings

overwhelm the inscape,

love or loss, rage or happiness.

The climate now, air of risk —

and one cannot speak, the ayin

and the aleph catches in the throat.

Adonai, Lord of the Waters, Lord

of the Firmament, Blake’s Ancient

of Days hovering in a cloud of wings.

Hawk in flight over me, fierce and

indifferent on the telephone wire, but

I can only feel his presence as a gift.

* * *

I can only feel his presence as a gift

dreamed him in the fire

snowlit moonlight half revealed him

יברכך יהוה וישמרך

יאר יהוה פניו אליך ויחנך

ישא יהוה פניו אליך וישם לך שלום

etched out upon the silver amulets

then in the siddur

the darkest knowable trace

his beauty slowly busy eating bitterbrush

reckon how now I know the name

for what can happen

near American Qumran

below the mountain

I the footstool, You the actual

Cloven Place

* * *

Cloven Place

Place of the Revealed

Backside of the God

Omnipotent Trickster

Forever departing

What might it mean

for the countenance

of such a One

to shine upon us?

to serve as the footstool

of such a One?

North of Fort Collins

and in East Walnut Hills

the American Qumran

in glorious isolation

waits to be discovered

* * *

waits to be discovered

from Fromm’s take on dreams

Scholem’s Ger Sham

Hasidism’s turn

to the inner worlds

where the ego longs to help the wheel

return to Nothingness

and other books

the body recovers in sleep

the world concealed

the dreamer is led to the silent ponds

a trickster longing for her dinner

her trout beneath the silent silver

Hebrew amulets

a pond’s paleographic countenance

mirroring devekut

ripples from the files

of the immanent foundation

immanence immense

but subtle presence

when you write me imperceptibly from the depths

You may call me Alanna

* * *

You may call me Alanna

she said to him in the poem

You may call me Alanna

she said to me in the poem

The poem speaks to us

imperceptibly from the depths

The depths speak to us

imperceptibly from the poem

But in the story, the depths

were set on fire

מְכַשֵּׁפָ֖ה לֹ֥א תְחַיֶּֽה

do not support the herbalist,

Pharmakia, or as Rothenberg has it,

shaman

Not a witch, and certainly not

to be put to death

Suffer them their livelihood

(פרנסה)

Suffer the small

acts of magic, little spells,

Old recipes for easing heartache

There in the woods

You would know what plants to gather

* * *

You would know what plants to gather

If your folk wisdom, that old medicine

Could survive outside its context

Without the folk

Build fire, altar, or dynamic center

For the story to change its worth

Elohim become herbarium of One

A disinherited practice

Bound to its altar

Preserves the old familiar

Nonetheless

Elohim conversant with adat-el

* * *

Elohim conversant with adat-el

as it is said:

מִזְמֹ֗ור לְאָ֫סָ֥ף אֱֽלֹהִ֗ים נִצָּ֥ב בַּעֲדַת־אֵ֑ל בְּקֶ֖רֶב אֱלֹהִ֣ים יִשְׁפֹּֽט

— “conversant” less defiant, less

aggressive than “takes His stand”

Judgment of the divine tribunal

the Solar Councils

as Duncan would have it (Passages 35):

“the Hosts of the Word that attend our words”

Psalm of Asaph, founder

of the musicians’ guild

commissioned by David

to sing in the Lord’s House

Song of a politics

in Heaven and Earth

“against the works of unworthy men,

unfeeling judgments, and cruel deeds”

Therefore

קוּמָה אֱלֹהִים, שָׁפְטָה הָאָרֶץ

But in Avot, the tribunal

becomes a study hall

and the Shekhinah abides among them.

* * *

Postface by the Authors

I first learned of Tirzah and her work through our friend Peter O’Leary, whose small press, Verge, was publishing Tirzah’s first book, Aleph. Peter sent me the book, which made an immediate impression on me, but it was not until sometime later that I wrote to Tirzah (February 4, 2019, to be precise), spurred by my reading of her remarkable essay on Gustaf Sobin and Kabbalah. In that first email, I shared my thoughts on Aleph: “It is a beautiful, audacious book, and its ‘elfin tefillin’ work a powerful magic. At first your minimalism frustrated me (though at times I have written in a similar mode): some of the fragments were so intensely lyrical and provocative that I wanted more. But now I think there is a special quality to the poems — what I called, in an essay I wrote years ago, ‘pressing for the end.’ Which, as you know, Jews are not to do. But which poets do continually.” Tirzah had read some of my work, as well, and it became clear that despite our differences — age, gender, lifestyle, but perhaps above all, our Jewish upbringings and experiences — we were deeply simpatico. Poetry and Jewishness (the poetry of Jewishness, the Jewishness of poetry) became a textual place which, exiles though we may be, we recognized as a shared homeland. We have yet to meet in person, haven’t even spoken by phone. The writing has been everything. Is it any wonder that a poetic dialogue should emerge?

As Tirzah explains below, the poems simultaneously create and exist within an imaginary eruv, the boundary of that textual place. It is a place of rest, and though the poetry can be turbulent, my sense throughout our writing has been that of a kind of Shabbos peace. As I reflect on the sequence, now that it is done, another Jewish concept comes to mind: the chavrusa or study partnership, the pair of friends (chaverim) reading Talmud together. “When two scholars of Torah listen to one another, God hears their voices” (Tractate Shabbat: 63a). Perhaps one has the image of two yeshiva buchers poring over an old tome, chanting and gesturing in the traditional style. Obviously, that’s not us! Nor does the idea of the chavrusa involve writing in the ordinary sense. But I still think that Tirzah and I are a chavrusa: our lives, especially our Jewish lives, but really everything that comes into the purview of our friendship, become the text which we both write and study. The give and take of the poems, the tension of pattern and free expression, the range of Jewish reference (sometimes in Hebrew or Yiddish), and the exuberance of the writing, are all signs of shared psychic attention. Two lives, two voices, but one poetic totality.

Here is an instance of our speaking to each other in terms of our daily experience and our shared Jewishness. A moose had been coming by the cabin where Tirzah and her husband Rico live. He seems to have taken on an almost sacramental quality, so that having mentioned him in her second poem (“singing, here, where no birds sing”), his reappearance in her third (“I can only feel his presence as a gift”) leads Tirzah to invoke the traditional priestly blessing, spoken on many occasions in the synagogue and inscribed upon amulets: “May the Lord bless you and guard you / May His Face shine upon you and be gracious unto you / May He lift up his Face unto you and grant you peace.” In the presence of a natural creature, this is, as I understand it, a decidedly unorthodox gesture, but one fraught with personal meaning. Furthermore, Tirzah had originally put the Hebrew words in the poem transliterated into English characters. But as I was working on the document, she asked me to put it into the original Hebrew letters. This meant a great deal to me; it gave me a certain permission, and led to my use of Hebrew phrases from various biblical passages in subsequent poems. Our use of the Hebrew characters has everything to do with the complex meanings of the phrases themselves in the context of our give and take. But it also signifies in and of itself; it is part of who and what we are, how we write and what that means to us and to our readers, whoever they may be. — Norman Finkelstein

One day I sent Norman a poem I was working on about an eruv and a fox afoot within its bounds. My co-religionist responded by using its last line — “all’s arc’s dark door to Torah”— as the first line of his own poem, followed by the question: “Your turn?” So began our dialogue, one that acts a little like an eruv or enclosure that blurs the difference between public and private domains for the purpose of carrying objects back and forth on Shabbos. The boundary line extended, poem after poem followed suit, each of us accepting the other’s end line as the beginning of one’s own poem — each of us believing, in fact, that the common line between us would disclose a series of original lines. Reading through our thirty-six disclosures (a numerical limit we set for ourselves along the way, thirty-six being twice חי , the Hebrew word for “life,” its letters amounting in gematria to eighteen), I see so clearly that what we’ve created is a space for Jewishness, somewhere to schmooze. I consider myself a Jewish poet — a Jewish poet rather more than an American poet. Writing for me is like going to shul — a shul, a synagogue, of one, however. But writing in collaboration with another Jewish poet (and a friend at that) takes on a different character. The space is in a different way permissive, the language held in common. The eruv stretches from East to West, from Cincinnati to rural Colorado, from a city rich in Jewish life to an environment where human beings are in the minority. (I live in a cabin off-grid, and my nearest neighbors visit their cabin infrequently on the other side of the mountain.) The space of our collaboration is rich because of its bounds, as any friendship is, any commons. I am increasingly interested in why and how any two people hold each other in common. The reasons are often mysterious, numinous. Instinct asks me not to press upon it too much.

— Tirzah Goldenberg

Poems and poetics