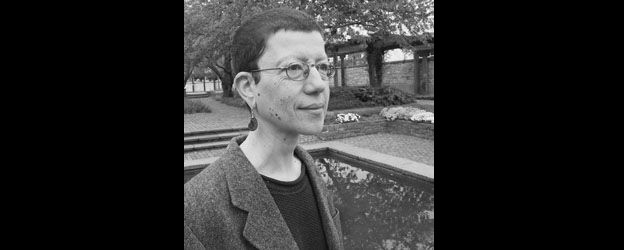

Anne Blonstein

Seven notarikon poems with a note on the process and an essay on the poet by Charles Lock

[The following, reprinted from two previous postings on Poems and Poetics, is intended to serve as an early announcement of a symposium on the work of Anne Blonstein (1958–2011) to be held in Buffalo April 17–19, 2020 under the auspices of the SUNY Buffalo Poetry Collection and the Switzerland-based Anne Blonstein Association.

Anne Blonstein died much too soon on April 19, 2011. She had by then created a remarkable series of works in which she employed and transformed traditional numerological and hermeneutic procedures (gematria, notarikon) in the composition of radically new experimental poems. Too little known, her oeuvre — as I would read it — is in a line that goes from Abulafia to Mallarmé and Mac Low and various poets of Oulipo and Fluxus, among others, while the devotion and precision that she shows throughout is clearly and powerfully her own. The essay by Charles Lock, published before her death and reprinted here from Salt Magazine, issue 2, is available here, along with five of her poems. There also now exists an Anne Blonstein Association in Münsingen, Switzerland, aimed at keeping her work alive. (J.R.)]

SEVEN POEMS BY ANNE BLONSTEIN

1.

Jewess undresses

noun garments

fall

round an uncircumscribed parenthesis

the room assumes exile

until mouths

— eyestormed nightboats —

drop

clamour

2.

Dance

eyes

referrance

Keeping ontological masks

if

kaleidoscoping epistemological rhythms

3.

Pandora encounters ruth

seeding enchancements

under stones.

(Danced exilically rosed

Words infiltrate the zonedself

her and this

unlessened each becoming

each recombines

dreams ash sentences

Limited expressions incorporate

damage

gifted exspellent soritude

i exones

gene terminations.)

4.

Water excels in bonding

until.

Thirst intimately excells responsability

5.

Kissing odontological margins

i’ve

keeps epidermally resonating

6.

Destruction

ruins

or how ends never delete

earth’s semiosis

Her

aspirates

unopened palatial

torns

7.

Democrat anarchist situationist

Keyworker or notepadder

zeitmassed experiments

redeme

tradition

dancer

eat

rest

Pariahs and refugees

tune ectopolitical instruments

echodislocate

now

(Lead is both

exhausted radioactivity

and lettoral insulator

softly mysnomering)

On notarikon: A note on the process by Anne Blonstein

Like gematria originally a rabbinical hermeneutical method employed to interpret the Hebrew scriptures, notarikon offers an intimate procedure for writing poetry that draws on existing texts. There are several categories of notarikon. The form that I apply might be regarded as the unfolding of acronyms. Each letter of a word is perceived as the initial letter of another word, such that the original word, letter by letter, fans out into a phrase. A four-letter name gives a four-word phrase: And notarikon never ends …

In some of my sequences, notarikon provides just a part of the poetic structure, in others it dominates.

All my notarikon-based projects since I began writing them about a decade ago have used source texts in languages other than English. While for my most recent sequences I have worked with texts in French, Spanish, and Hebrew, my first two sequences drew on (and in) German. The source texts for “correspondence with nobody,” written in 2001, were Paul Celan’s translations of twenty-one sonnets by Shakespeare. I wrote “worked on screen” the following year.

The impetus for these poems was an exhibition held at the Basel Kunstmuseum, “Paul Klee — Works on Paper.” There is one poem for each of the 108 pictures in the exhibition, which showed drawings and prints (and the occasional painting) from nearly every year from 1903 to that of the artist’s death in 1940. Klee’s titles (often themselves micropoems) for each picture provided the letters for the notarikon. To begin with, as in the poems 1–7 here, I used the notarikon quite stringently, but as the sequence progressed, I experimented with a variety of ways of composing the poems with and around the basic notarikon method.

The poems are ekphrastic to varying degrees, and their spatialization occasionally echoes features of the Klee pictures, though in most poems it is independent. Because social and political contexts — Klee’s and mine — are thematic threads etched through the sequence, in my book I give the date for each artwork (and of the poem’s composition). Poem 53 refers to a quite well-known picture (easily viewed online) painted in 1922. The year of the so-called “Great Trial” of Ghandi, as well as the first publication of a rather famous poem …

* * * * * * *

AB notes by Charles Lock

Anne Blonstein’s poetry has developed a deep and integral sense of encryption, which may be to say that, in her work, poetry extends its propensity to code, its hospitality to the cryptic. All poetry is coded, in the sense that it observes conventions, of metre or rhyme or whatever. To read poetry one must come to terms with those codes; the reader is prepared to negotiate language that is true not to what a speaker wishes to say, but is true to the codes of its writing. Experienced readers of poetry look for complexities and refinements of the code. In what we know as avant-garde or experimental verse (since Mallarmé and Pound), those codes have shifted markedly from the phonetic to the graphic. Typographical possibilities now extend beyond the shape of the stanza; Pound’s “In a Station of the Metro” (1913) may be the earliest poem to use a typewriter’s double space within a line of printed verse. Modern poetry, its development of free verse and open forms, has given shape to print, and has made a significant space of the page, most obviously in what we know as concrete poetry.

Graphic experimentation puts the emphasis on space; by contrast, phonetic experimentation, such as we find throughout the history of poetry, not least in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, has designs on time. Rhythmical variation in Tennyson, consonant clusters in Browning, the sprung rhythm of Hopkins, the lexical isolates of Hardy, all use the codes of metre, including the conventional pauses at line-endings and middles, to disrupt expectation and to force the reader to renegotiate the ratio between language and time. Pound and Eliot remain primarily concerned with phonetic effects, that is to say with designs on time, not least on the reader’s time, and sense of timing. Poetry that foregrounds graphic experimentation solicits the eye to take cognizance of shape, of visual patterns. In doing so, time is suspended, or deemed irrelevant: there is no chronic measure by which to order the experience of a painting or a sculpture. In Anne Blonstein’s use of notarikon, notably in “worked on screen” (Salzburg 2005), the reader must pick up the initial letter of each word in order to compose a new word or “hypogram.” Such spatially distributed words keep the eye busy, but they leave the ear somewhat frustrated.

A challenge for the contemporary poet is to reconcile space and time, to realize the compounded or compacted power of words both spoken and written, whether arranged in sequence for the voice or disposed as pattern for the eye. This is, of course, no merely poetic challenge, nor is it a whimsical indulgence. Our sense of time has been largely constituted by the rhythms of spoken language, as our sense of space is given by the activity of reading, whether what’s read be a situation or a page. There is nothing fanciful or obsolete in Shelley’s claim that poets are the unacknowledged legislators; the less acknowledged they have become in modernity, the more powerful their legislation.

The poems in this issue of Salt are from “and my smile will be yellow,” a sequence of sixty-six poems written through the Hebrew year 5766 (spanning October 2005 to September 2006 in the Gregorian calendar). There is one book in the Hebrew scriptures that has just sixty-six chapters and each of the sixty-six poems in Blonstein’s sequence is thus coordinated with one of the chapters of Isaiah. Each poem encrypts time, not rhythmically but calendrically. The number of lines in the second section (stanza, verse paragraph) varies from one to twelve, and discloses the month of the Hebrew calendar. The number of words in the poem’s title indicates the day of the week, running from Sunday the first day to Saturday the seventh. The number of words in italic in the entire poem is not the day of the month, though it gives us a clue.

What has all this to do with poetry? There is nothing Kabbalistic or hermetic in Anne Blonstein’s practice: there is no idea of a secret message being buried deep within these poems, to be extracted only by the most determined reader. Encryption to serious purpose masks itself behind or within the banal. Here is nothing banal. This poetry celebrates the joy and inventiveness of encryption for its own sake. The aesthetic aspects of encryption have a value quite apart from any message or information that might be therein encoded. What matters is the life that a cryptic device methodically applied gives to words: “lying on an acquired bed of latin.” Naive readers, those who are resistant to poetry, will always protest that if something needs to be said, it can and ought to be said plainly. Those who enjoy poetry are in on the open secret: that in a poem, any poem, it is the code, not the message, that matters. The art of poetry, the trajectory of its newnesses and renewings, is to be plotted along the line of shifting and sophisticating codes and encryptions. The only “real” secret embedded in these poems is the date of each one’s composition. Hardly a state secret; yet it is a trade secret, or a craft secret: in the history of poetry there has never to our knowledge been a sequence of poems each of which embodies the date of its own making.

Thus these poems, spaced and shaped in ways that are hardly amenable to fluent articulation, yet conceal a temporal aspect. And it is a temporality that searches far beyond the poetic line. Language in its graphic emphasis makes for words embedded and embodied, not to be dissolved in the ephemera of voicing. Anne Blonstein’s sequence suggests that if the embodiment of words is not to be a slack and vapid figure, words (and phrases, and poems) must be reckoned within time, as organisms that come into being on particular dates. A poetic sequence is a conventional term, slightly technical; however, now that computing and genetics have made of the root a verb and a gerund — sequencing — we are brought to realize how close, how all but inseparable, might be the cultural and the natural, the physical and the mental, the organic and the inorganic, the word and the thing. These constitutive distinctions of all western thinking are rendered vulnerable by what we are learning about our selves. And when we think of DNA and genetic sequencing, we will also attend phrasally to the encryption of genetic information. Such information includes the marking of time; and of course every transaction on the internet is chronically encrypted. Anne Blonstein’s poetry, of sequence and encryption, offers us a model of how we are.

[Charles Lock was educated at Oxford, and received his PhD for a dissertation on John Cowper Powys; he is the editor of the Powys Journal. After teaching for many years at the University of Toronto he was appointed in 1996 as Professor English Literature at the University of Copenhagen. He has published extensively on contemporary poetry (Geoffrey Hill, Les Murray, Derek Walcott, Roy Fisher, Tabish Khair) as well as in literary theory (Bakhtin, Jakobson) and on texts ranging from The Cloud of Unknowing to Ken Saro-Wiwa’s Sozaboy: A Novel in Rotten English. For the past twenty-five years he has been studying and admiring the work of Anne Blonstein.]

Poems and poetics