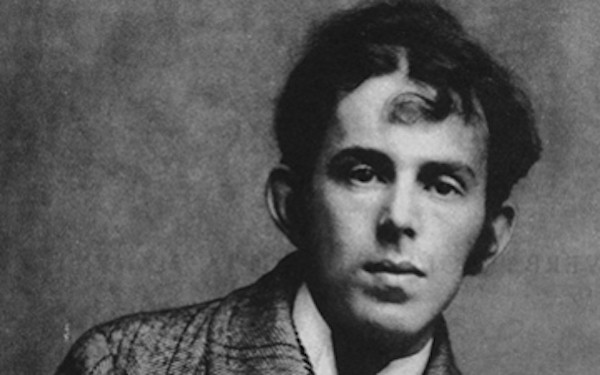

Thoughts on Osip Mandelstam's birthday

A birthday that happened 125 years ago today... & still I can't find an English translation that satisfies me completely. Most of them feel more or less flat, with Mandelstam turned into a most salon-fähig lyrical poet of medium to low intensity. (Oddly enough this is true especially of those translations extolled by Joseph Brodsky, someone who should have know, as he was a native Russian who wound up writing in English, but I guess my judgment here may be tainted as I find Brodsky's English work très fade...) Clarence Brown's versions may still be the least problematic, but I can't wait for John High's complete Mandelstam (his collaborative versions with Matvei Yankelevich are lovely indeed) — John, we need these! I have not yet been able to get Andrew Davis' just published versions of the Voronezh Notebooks, out earlier this month from NYRB Poets. Way back when — late sixties — my Bard College co-student Bruce McClelland published a translation of Tristia, which I found useful and quite readable back then. I wish he had continued to work on Mandelstam, but unhappily his interests wandered elsewhere.

What I have come to realize over the years is that the translation of truly major poets (of which Mandelstam is one) cannot be approached as an occasional occupation, i.e. as either a quick way to learn the tricks of a master (translating is the closest reading you can give a poem, so indeed the most useful activity in learning to write, as I have been telling my students for many years) or as a way to locate possibilities of publication by associating one's (as yet unknown) name with that of a well-known poet (though that too can be useful for a serious young poet). Looking at such multiple scatter-shot translations, in magazines, chapbooks or single volumes of major poets by numerous translators, gives me at times the impression of a haphazard gaggle of young (or not so young) poet-translators cutting their teeth by feeding on the giant corpse of a dead beached whale. At the same time, I'd like to add, having several translations of a great poem can also be of good comparative use.

Just as one does not become a poet by absolving a 2-year MFA (even if the institution would seem to suggest this by giving the MFA graduate the legal right to teach his or her craft once the diploma has been framed), it would be better to approach such a major foreign poet not only with the humbleness of the beginner but also with the desire for an open-ended apprenticeship that may even turn out to be be life-long. Exemplary for me, in that sense, is Clayton Eshleman's decades-long translation work on César Vallejo — a work Eshleman has linked to Charles Olson's proposal in "A Bibliography on America for Ed Dorn" for a "saturation job" that would get the young poet "in" once and for all. (A saturation job, Olson explains, consists in learning everything that can be learned & known about something — a man, an event, a thing, so that you know more than anyone else about this.)

Another man who has spent his life working in such a way is the Swiss poet, translator, essayist Ralph Dutli, who besides his own work (which also includes an excellent novel on the painter Chaim Soutine's last days) has edited, translated & published a 10-volume edition of Mandelstam's works (the poems in both languages) as well as writing four volumes of essays on OM, plus the best biography of Mandelstam we have. A major oeuvre of which the essays and the biography should be translated into English!

Now, despite the fact that I do admire and use Dutli's German translations, I tend to read Mandelstam's poetry in Paul Celan's German versions — for me, who doesn't have Russian, the best and richest versions. Celan also wrote a radioplay on Mandelstam for two voices — a version of which with Charles Bernstein & me "doing the voices" was recorded late last year & should be available this spring as a podcast (the text can be found in The Meridian, published a few years back by Stanford University Press). It contains several poems by Mandelstam in Celan's translations — & which I thus had to translate from Celan's German into English. Let me close this meditation on translation on Mandelstam's birthday with the last of those poems framed by Celan's speakers:

Speaker 1: In 1928 a further volume of poems appears – the last one. A new collection joins the two previous ones also gathered in it. “No more breath – the firmament swarms with maggots!": this line opens the cycle. The question about the where-from becomes more urgent, more desperate – the poetry – in one of his essays he calls it a plough – tears open the abyssal strata of time, the “black earth of time” appears on the surface. The eye, talking with the perceived, and pained, develops a new ability: it becomes visionary: it accompanies the poem into its underground. The poem writes itself toward an other, a “strangest” time.

JANUARY1924

Whoever kisses time’s sore brow

will often, like a son, think tenderly

how she, time, laid down to sleep outside

in high heaped wheat drifts, in the corn.Whoever has raised the century’s eyelid

– both slumber-apples, large and heavy – ,

hears noise, hears the streams roar

the lying times, relentlesslyImperious century, with loam-beautiful mouth

and two apples, asleep – yet

before it dies: to the son’s hand, so shrunken,

it bends down its lip.Life’s breath, I know, ebbs away each day,

one more small one, a small one – and

deceased is the song of mortification, loam and plague,

with lead they seal your mouth.Oh loam-and-life! Oh century’s death!

Only to the one, I’m afraid, does its meaning reveal itself,

in whom there was a smile, helpless – to the inheritor,

the man who lost himself.Oh pain, oh to search for the lost word.

oh lid and lid to raise, sick and weak,

for generations, the strangest, with lime in your blood

to gather the grass and the weed of night!Time. The lime in the blood of the sick son

turns hard. Moscow, that wooden coffer, sleeps.

Time, the sovereign. And no escape anywhere...

The snow’s apple-scent, as always.The sill here: I wish I could leave it.

Whereto? The street – darkness.

And, as if it were salt, so white, there on the pavement

lies my conscience, spread out before me.Through winding lanes, through slipways

the journey goes, somehow:

a bad passenger sits in a sled

pulls a blanket over the knees.The lanes, the shimmering lanes, the by-lanes

the runners crunch’s like apples under the tooth.

The strap, I can’t grab it,

it doesn’t want me to, and the hand is clammy.Night, cartwoman, with what scrap and iron

are you rolling through Moscow?

Fish thud here, and there, from pink houses,

it steams toward you – scalegold!Moscow, anew. Ah, I greet you, once more!

Forgive, excuse – my misery wasn’t very great.

I like to call them, as always, my brethren:

the pike’s saying and the hard frost!The snow in the pharmacy’s raspberry light...

A clattering, from afar, an Underwood...

The coachman’s back... the roadway, blown away...

What more do you want? They won’t kill you.Winter – beauty. And skyward the white,

the starmilk – it streams, streams away and blinks.

The horsehair blanket crunches along the icy

runners – the horsehair blanket sings!The little lanes, smoking, the petroleum, always – :

swallowed by snow, raspberry colored.

They hear the Soviet-sonatina jingle,

remember the year twenty.Does it make me swear and damn?

– The frost’s apple-scent, again –

Oh oath that I swore to the fourth estate!

Oh my promise, heavy with tears!Oh whom will you kill? Whom will you praise?

And what lie, tell me, are you going to make up?

Tear off this cartilage, the keys of the machine:

the pike’s bones you lay open.The lime in the blood of the sick son: it fades.

A laughter, blissful, frees itself –

Sonatas, powerful... The little sonatina

of the typewriter – : only its shadow!2. Speaker: That’s how to escape contingency: through laughter. Through what we know as the poet’s “senseless” laughter – through the absurd. And on the way there what does appear –mankind is absent – has answered: the horsehair blanket has sung. Poems are sketches for Being: the poet lives according to them. In the thirties Osip Mandelstam is caught in the “purges.” The road leads to Siberia, where we lose his trace. In “Journey to Armenia,” one of his last proses published in 1932 in the Leningrad magazine “Swesda,” we also find notes on the matters of poetry. In one of these notes Mandelstam remembers his preference for the Latin Gerund.

The Gerund ! that is the present participle of the passive form of the future.

Nomadics