Pier Paolo Pasolini: Eight poems for Ninetto (1970–73)

Translation from Italian & Commentary by Peter Valente

[These poems are part of a sequence whose central focus is Pasolini’s love for the young actor Ninetto Davoli. They are selected from the 112 works that exist in various states of draft and revision, most of them written during the filming of the “Canterbury Tales” in England and completed on Pasolini’s return to Italy. The last poem in the sequence is dated “February 1973.”]

1/

Your place was at my side,

and you were proud of this.

But, sitting with your arm on the steering wheel

you said, “I can’t go on. I must stay here, alone.”

If you remain in this provincial village you’ll fall into a trap.

We all do. I don’t know how or when but you will.

The years that comprise a life vanish in an instant.

You are quiet, pensive. I know it is love

that is tearing us apart.

I have given you

all the power of my existence,

yet you are humble and proud, obeying a destiny

that wants you to remain impoverished. You don’t know

what to do, whether to give in or not.

I can’t pretend your resistance

doesn’t cause me pain.

I can see the future. There is blood on the sand.

Canterbury

2/

I think of you and I say to myself: “ I have lost him.”

I cannot bear the pain and wish I were dead. A minute

or so passes and I reconsider. With joy

I take back strength from your image. I refuse to cry.

My mind is changed.

Then again I consider you, lost and alone.

Who is this ugly gentleman

who does not understand what concerns him most? Are you

or are you not this Other,

he who always loses without really dying?

He is my double: I, pedantic. He, informal.

Knowledge of him has changed everything in my life.

He says that if I am lost he will find me.

He knows that when he does I will be dead.

Bath, October 24, 1971

3/

That Freud that you enjoy reading doesn’t

clarify what I desire. You came here,

and I repeat –Nothing binds you to me.

Yet you decide to stay.

The man who prays and does not feel shame, who desires

his mother’s nest for comfort, will lead a false life.

A desolate life. You will deny this.

But remember his cry is not for you.

It is for his own ass.

You came to teach me things I had not known before

but the angel appears and you are silent again.

He is soon gone. And still you are anxious.

Pleasure suspends my anguish.

But I know afterwards regret will shatter our fragile peace.

4/

There existed in this world a thing without price.

It was unique. Few were aware of it.

No code of the Church could classify it.

I confronted it midway on life’s journey

with no guide to lead me through this hell.

In the end there was no sense in it

tho it consumed the whole of my reality.

You wanted to destroy any good that came from it,

slowly, slowly, with your delicate hands.

You were not devoted and yet I cannot understand

why there was so much fury in your soul

against a love that was so chaste.

Benevento, Feb. 3, 1973

5/

The wind screamed through the Piazza dei Cinquecento

as in a Church –there was no sign of filth.

I was driving alone on the deserted streets. It was almost 2 am.

In the small garden I see the last two or three boys,

neither Roman nor of the peasantry, cruising for

1000 lire. Their faces are stone cold. But they have no balls.

I stopped the car and called out to one of them.

He was a fascist, down on his luck, and I struggled

to touch his desperate heart.

But in the dark I could see himwatching me.

You have come with your car and had your fun, Paolo.

The degenerate individual was here next to you. He is your double.

Cheap stolen trinkets hang from his car window.

Now you must leave

but where can you go? He is always there.

6/

When you have been in pain for so long

and for so many months it has been the same, you resist it,

but it remains a reality in which you are caught.

It is a reality that wants only to see me dead.

And yet I do not die. I am like someone who is nauseous

and does not vomit, who does not surrender

despite the pressure of Authority. Yet, Sir,

I, like the entire world, agree with you.

It is better that we are kept at a far distance.

Instead of dying I will write to you.

In this way, I preserve intact my critique

of your hypocritical way of life,

which has been my sole joy in the world.

London Airport, November 14, 1971

7/

After much weeping, in secret

and in front of you, after having staged

many acts of desperation, you made

the final decision to surrender

and never to be seen again. I am done.

I have acted like a madman. I will not let the water run

from the source of my evil and my good:

these pacts between men are not for you or perhaps

you’re too skilled in the art of breaking them,

guided by a Genie that gives you certainty

by which you are transfigured. You

know the right button to push.

When I speak you tell me “no”

and I tremble with disgust and fury

at the thought of our unforgettable happy hours.

Rome, January 13, 1972

8/

After a long absence, I put on a record of Bach, inhale

the fragrant earth in the garden, I think again

of poems and novels to be written and I return

to the silence of the morning rain,

the beginning of the world of tomorrow.

Around me are the ghosts of the first boys,

the ones you knew. But that is over. Their day

has passed and, like me, they remain far from the summit

where the sun has made glorious their heads,

crowned with those absurd modern-style haircuts

and those ugly American jeans that crush the genitals.

You laugh at my Bach and you say you are compassionate.

You speak words of admiration for my dejected brothers of the Left.

But in your laughter there is the absolute rejection of all that I am.

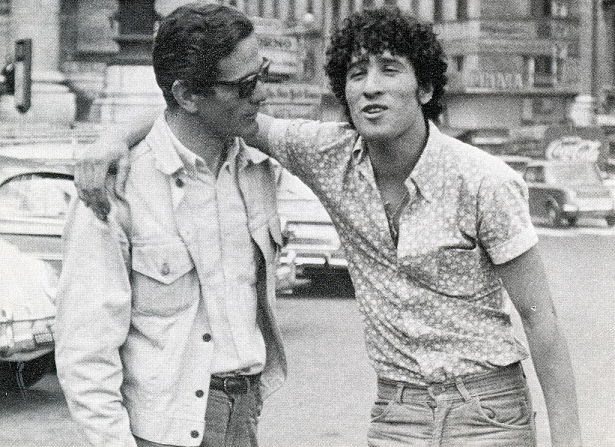

NOTE. Giovanni (“Ninetto”) Davoli was born on October 11, 1948 in San Pietro a Maida, Calabria. During the shooting of “La Ricotta” (1963), he was introduced to Pasolini. He was fourteen years old. Pasolini had just turned forty. Pasolini wrote, “Everything about him has a magical air…an endless reserve of happiness.” Soon Ninetto became part of Pasolini’s entourage and began appearing in his films. He was first cast in “The Gospel According to St. Mathew” (1964) and appeared in many others films culminating with “The Arabian Nights” in 1974. He has said of his relationship to Pasolini, “In me, he found the naturalness of the world he knew growing up.” This was the world that Pasolini saw devastated and ultimately obliterated by the changes that Italy was undergoing in the 60s.

Ninetto told Pasolini, during the filming of the “Canterbury Tales”, that on his return to Rome he intended to marry. Pasolini writes, “I am insane with grief. Ninetto is finished. After almost nine years, there is no more Ninetto. I have lost the meaning of my life…Everything has collapsed around me.” In January 1973, Ninetto married. He promised Pasolini that nothing fundamental would change as a result of his marriage. But Pasolini was inconsolable.

The poems begun on August 20, 1971 chart the series of emotional upheavals Pasolini underwent during the time leading up to and after the wedding. He writes that Ninetto “is tired of our relationship. It has lost / all sense of novelty for him. The duty of a new life / distracts him.” He writes of Ninetto’s fiancée , “She blamed you for your innocent abandonments…She wants everything./ She is desperate and without hope, / without any compassion.” In another poem he accuses Ninetto, “This love/ does not glorify you. It humiliates you. /…You love her only if she weeps and is humiliated./You don’t know how to maintain her / nor do you really want to.” His anger turns to regret: “But you, so happy, you/ the very image of happiness, now/ that you are gone from my life.” Finally his anger subsides and he writes on February 1, 1973, “But seeing that you have retained a little love for me / exclusively, this means everything.” Pasolini’s relationship with Ninetto had changed into something else. Desire had given way to affection and loyalty. Pasolini cast him as Aziz in the “Arabian Nights,” a character he described as “joy, happiness, a living ballet.” Ninetto’s first son was named Pier Paolo.

Poems and poetics