Poem going down the drain (PoemTalk #45)

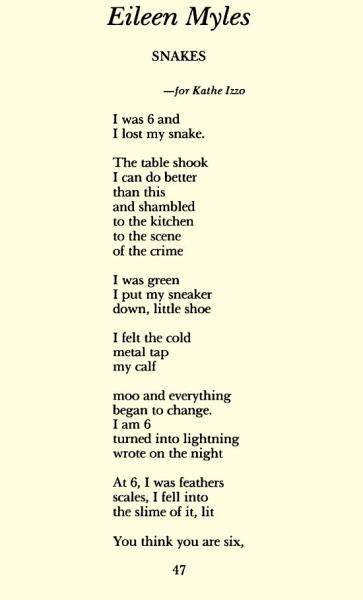

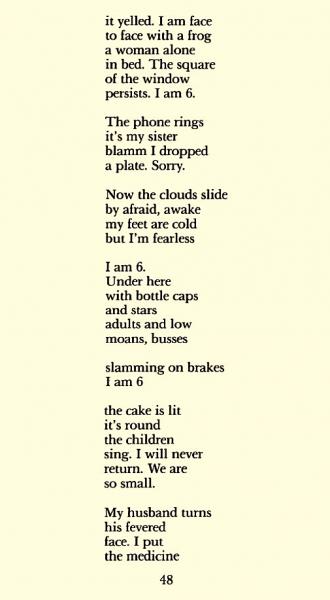

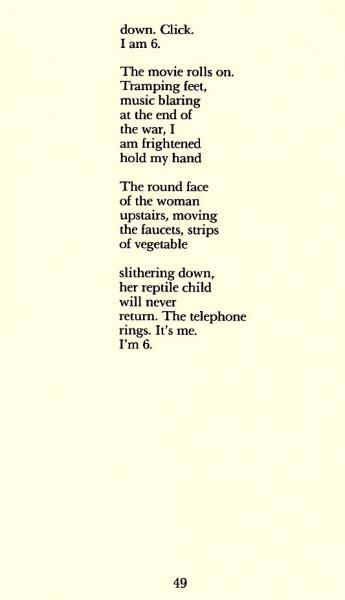

Eileen Myles, 'Snakes'

Eileen Myles wrote “Snakes” just as they were assigning children in a friend’s Provincetown poetry workshop to write a poem with the following not-so-constraining-seeming constraint: “Be any age and go down the drain with it.” Their poem, then, is something of a pedagogical model, an exercise in teaching by participation. Or perhaps the assignment they gave the students simply felt so alluring to them — befit their own aesthetic so well — that they couldn’t help but try it themself, regardless of their role as young writers’ guide. This was in 1997 or so. By January 1998 they were reading the poem at the Ear Inn in New York. It was published in The Massachusetts Review also in 1998.

Sarah Dowling, Michelle Taransky, and Charles Alexander (Charles was visiting from the Southwest, and delighted us with a poetry reading the same day) joined Al Filreis in Al’s studio office at the Kelly Writers House to discuss this poem. Charles had spoken with Eileen Myles before the recording and was able to confirm our hunch about the poem’s derivation from the workshop exercise. Then Charles wonders aloud: once we establish that specific motive or origin for the poem, we must ask what does putting something — let alone a poem — down the drain mean, and how does it manifest itself in the writing itself? Charles begins that part of our discussion by suggesting that it might be something akin to going down the rabbit hole. Memory moving crossways and around — quick-cut fast and time-disordering slow at once.

Some kind of domestic memories (not surprising given the poem’s emergence out of the subject position of a six-year-old). Michelle Taransky hears and identifies domestic details, such that the going-down-the-drainness of the poem seems to connect us with a vortexical memory of the domestic situation in the child. Charles senses that the six-year-old seems mostly unaware of the loss. Michelle notes the percussiveness of phrases varying from “I was 6,” and suggests that the poem is about a collision of perspectives: being the non-six-year-old (an adult teacher-poet “doing” six) and, in the present of the poem’s drained fiction, being persistently just six.

Some kind of domestic memories (not surprising given the poem’s emergence out of the subject position of a six-year-old). Michelle Taransky hears and identifies domestic details, such that the going-down-the-drainness of the poem seems to connect us with a vortexical memory of the domestic situation in the child. Charles senses that the six-year-old seems mostly unaware of the loss. Michelle notes the percussiveness of phrases varying from “I was 6,” and suggests that the poem is about a collision of perspectives: being the non-six-year-old (an adult teacher-poet “doing” six) and, in the present of the poem’s drained fiction, being persistently just six.

Al asks how much temptation there is to read the poem allegorically. Sarah responds by thinking through the importance of the snake. “I lost my snake,” she quotes. For her, the lost figure casts its curling shadow over the rest of the poem. Does the snake belong to the “I” (as a pet, it seems), the poem’s speaker at the beginning? Okay, but then the snake seems also to be the “reptile child” we see toward the end. Sarah comes to believe that “Snakes” is about a domestic moment of loss. The loss of self, the loss of a daughter from a mother (the “I” with the husband?), the loss of the reptile-child self. The group sees evidence in the poem that being six years old can convey a disempowering sensation in extremis. The repetition of “I am 6” is at times “silly” (also at times “comic booky”) but creates a sense of entrapped stupidity — a way of feeling in advance what it’s going to be like to be unsuccessful at being an adult. Al several times proffers an historical reading of the situation as specifically a Cold War-era domesticity; this is not so much taken up by the others as accepted as contributing to the overall heightened sense of feared big loss, tramping feet with music blaring at the end of the war, comic-book-sized quasi-allegory about runaway reptiles, domestication gone awry, etc.

James LaMarre was our director and engineer, while Steve McLaughin, as always, edited this episode.