For over twenty years, Steve Clay’s Granary Books has brought together writers, artists, and bookmakers to investigate poetic and visual relations in the time-honored spirit of independent publishing. Granary’s mission—to produce, promote, document, and theorize new works exploring the intersection of word, image, and page—has earned the publisher a reputation as one of the most unique and significant small publishers operating today. Archivist, author, curator, and publisher Steve Clay has written:

The first item that I identify as a Granary Books publication was actually published by Origin Books in 1986—Wee Lorine Niedecker by Jonathan Williams. It embodies several elements that remain important to me now, some fifteen years later, among which is an acute awareness of the “book” as a physical object.

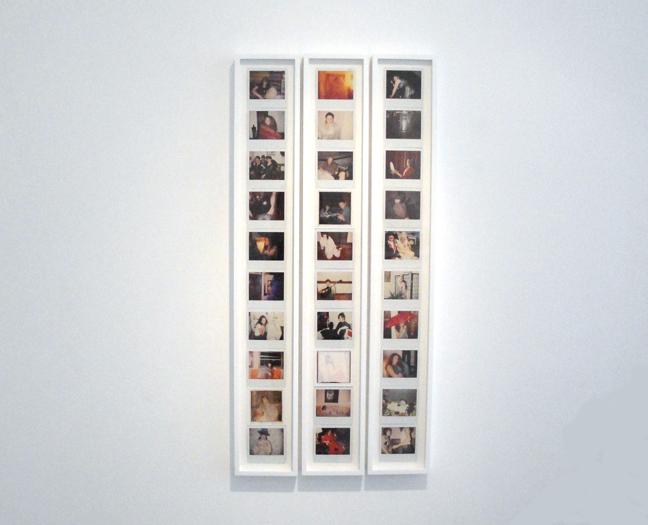

Emma Bee Bernstein's Polaroid show opened at the Microscope Gallery, Thursday night, May 24th, 2012. The curator Phong Bui did a stellar job with the selection, framing, and installation. There were six horizontal custom frames with 20 of the original Polaroids (73 x 7 1/4 in) and four vertical frames with 10 of the original Polaroids (6 1/2 x 43 in). A number of single Polaroids, two framed, were also exhibited, along with two notebooks with Polaroids inlaid. In addition to the original Polaroids, singles and in the framed sets, Microscope is also making color pigment prints of the original Polaroids, 8 x 10 inches on archival paper (editions of 9). Any of the Polaroids in the exhibit is available as a print. Any inquires about acquiring the Polaroid sets, individual Polaroids, or the prints should be made directly to Microscope Gallery: info@microscopegallery.com or call them at 347-925-1433. Microscope can provide for individual viewing a full set of images. Microscope is also screening Emma's film, Exquisite Fucking Boredom; it is available from the gallery as a limited edition DVD.

image from Dear Sammy: Letters from Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas

There are few things I love more than reading Stein’s “If I Told Him: A Completed Portrait of Picasso” with a composition class. I choose to focus on this poem (both as the class’s first interaction with Stein and as the topic of this post) because I think the repetition is irresistible and always suspect that when meeting Stein’s “Picasso” students might finally see writing as “play” instead of required task. In “The Difficulties of Gertrude Stein,” Joan Retallack reminds us that “there’s an intense need for play when one is in a particularly untenable situation like adulthood” (159). And, what situation seems more untenable in the moment as being a burgeoning adult in a required class that makes you write?

Once absorbed in a text that circles in and out of itself, I think students see that even written language has the potential for change and to change. And, in thinking about Stein’s repetition alongside their own processes of writing and rewriting and revising, students realize that no text needs to be permanent. As Stein writes in “Composition and Explanation,” “the composition is the thing seen by every one living in the living they are doing, they are composing of the composition that at the time they are living is the composition of the time in which they are living” (Selections 218). Similarly, Sondra Perl links the writing process to time and movement in “Understanding Composing.” Perl writes, “writing is a recursive process, that throughout the process of writing, writers return to substrands of the overall process…In other words, recursiveness in writing implies that there is a forward-moving action that exists by virtue of a backward-moving action.”

A recent issue of The Capilano Review focused on “ecologies,” gathering work that some people might want to assemble under the heading of “ecopoetics.” It is still not the easiest literary brand to define, with capacious boundaries and more questions than answers (which is what keeps it interesting, despite the fact that a lot of work that we once called, with a yawn, “nature poetry,” now cuts a more dashing figure under the heading “ecopoetics”). Nevertheless, I did find myself doing a double take at the inclusion here of Christian Bök’s “The Extremophile,” which was even the subject of a series of featured responses at the issue’s official launch. Is Bök’s work an example of “ecopoetics” (whatever that might turn out to be)?

Of course, Bök is already associated with a strong brand—conceptualism—though that doesn’t mean he can’t double-down. But let’s back up just a bit.

“The Extremophile” is a poem that introduces us to deinococcus radiodurans, the “hero,” if you will, of The Xenotext, Bök’s ambitious and long-awaited follow-up to Eunoia. Radiodurans is the eponymous “extremophile” of the poem’s title—a bacterium so classified because of its resistance to, well, almost everything.

PennSound’s Creeley collection includes five recordings of the poet performing “I Know a Man,” as follows:

(1) read at San Francisco State University, May 20, 1956 (0:28): MP3 (2) at the Vancouver Poetry Conference, August 12, 1963 (1:27): MP3 (3) read at Harvard University, October 27, 1966 (0:35): MP3 (4) read in Bolinas, CA, July 1971 (0:26): MP3 (5) read in Bolinas, CA, c. 1965-1970 (0:25): MP3

Episode 16 of PoemTalk is a 30-minute discussion of this poem with Bob Perelman, Jessica Lowenthal, and Randall Couch.

'Bean Spasms'

For over twenty years, Steve Clay’s Granary Books has brought together writers, artists, and bookmakers to investigate poetic and visual relations in the time-honored spirit of independent publishing. Granary’s mission—to produce, promote, document, and theorize new works exploring the intersection of word, image, and page—has earned the publisher a reputation as one of the most unique and significant small publishers operating today. Archivist, author, curator, and publisher Steve Clay has written:

The first item that I identify as a Granary Books publication was actually published by Origin Books in 1986—Wee Lorine Niedecker by Jonathan Williams. It embodies several elements that remain important to me now, some fifteen years later, among which is an acute awareness of the “book” as a physical object.

Exquisite Fucking Charms: on Emma's Polaroids

Emma Bee Bernstein at Microscope Gallery

Emma Bee Bernstein's Polaroid show opened at the Microscope Gallery, Thursday night, May 24th, 2012. The curator Phong Bui did a stellar job with the selection, framing, and installation. There were six horizontal custom frames with 20 of the original Polaroids (73 x 7 1/4 in) and four vertical frames with 10 of the original Polaroids (6 1/2 x 43 in). A number of single Polaroids, two framed, were also exhibited, along with two notebooks with Polaroids inlaid. In addition to the original Polaroids, singles and in the framed sets, Microscope is also making color pigment prints of the original Polaroids, 8 x 10 inches on archival paper (editions of 9). Any of the Polaroids in the exhibit is available as a print. Any inquires about acquiring the Polaroid sets, individual Polaroids, or the prints should be made directly to Microscope Gallery: info@microscopegallery.com or call them at 347-925-1433. Microscope can provide for individual viewing a full set of images. Microscope is also screening Emma's film, Exquisite Fucking Boredom; it is available from the gallery as a limited edition DVD.

Any of the Polaroids in the exhibit is available as a print. Any inquires about acquiring the Polaroid sets, individual Polaroids, or the prints should be made directly to Microscope Gallery: info@microscopegallery.com or call them at 347-925-1433. Microscope can provide for individual viewing a full set of images. Microscope is also screening Emma's film, Exquisite Fucking Boredom; it is available from the gallery as a limited edition DVD.

Portraits & grammar

Gertrude Stein, a lesson play

There are few things I love more than reading Stein’s “If I Told Him: A Completed Portrait of Picasso” with a composition class. I choose to focus on this poem (both as the class’s first interaction with Stein and as the topic of this post) because I think the repetition is irresistible and always suspect that when meeting Stein’s “Picasso” students might finally see writing as “play” instead of required task. In “The Difficulties of Gertrude Stein,” Joan Retallack reminds us that “there’s an intense need for play when one is in a particularly untenable situation like adulthood” (159). And, what situation seems more untenable in the moment as being a burgeoning adult in a required class that makes you write?

Once absorbed in a text that circles in and out of itself, I think students see that even written language has the potential for change and to change. And, in thinking about Stein’s repetition alongside their own processes of writing and rewriting and revising, students realize that no text needs to be permanent. As Stein writes in “Composition and Explanation,” “the composition is the thing seen by every one living in the living they are doing, they are composing of the composition that at the time they are living is the composition of the time in which they are living” (Selections 218). Similarly, Sondra Perl links the writing process to time and movement in “Understanding Composing.” Perl writes, “writing is a recursive process, that throughout the process of writing, writers return to substrands of the overall process…In other words, recursiveness in writing implies that there is a forward-moving action that exists by virtue of a backward-moving action.”

Christian Bök and the quest for immortality

A recent issue of The Capilano Review focused on “ecologies,” gathering work that some people might want to assemble under the heading of “ecopoetics.” It is still not the easiest literary brand to define, with capacious boundaries and more questions than answers (which is what keeps it interesting, despite the fact that a lot of work that we once called, with a yawn, “nature poetry,” now cuts a more dashing figure under the heading “ecopoetics”). Nevertheless, I did find myself doing a double take at the inclusion here of Christian Bök’s “The Extremophile,” which was even the subject of a series of featured responses at the issue’s official launch. Is Bök’s work an example of “ecopoetics” (whatever that might turn out to be)?

Of course, Bök is already associated with a strong brand—conceptualism—though that doesn’t mean he can’t double-down. But let’s back up just a bit.

“The Extremophile” is a poem that introduces us to deinococcus radiodurans, the “hero,” if you will, of The Xenotext, Bök’s ambitious and long-awaited follow-up to Eunoia. Radiodurans is the eponymous “extremophile” of the poem’s title—a bacterium so classified because of its resistance to, well, almost everything.

Five recordings of Creeley performing 'I Know a Man'

PennSound’s Creeley collection includes five recordings of the poet performing “I Know a Man,” as follows:

(1) read at San Francisco State University, May 20, 1956 (0:28): MP3

(2) at the Vancouver Poetry Conference, August 12, 1963 (1:27): MP3

(3) read at Harvard University, October 27, 1966 (0:35): MP3

(4) read in Bolinas, CA, July 1971 (0:26): MP3

(5) read in Bolinas, CA, c. 1965-1970 (0:25): MP3

Episode 16 of PoemTalk is a 30-minute discussion of this poem with Bob Perelman, Jessica Lowenthal, and Randall Couch.