‘And whoever picks it up grabs the magic’

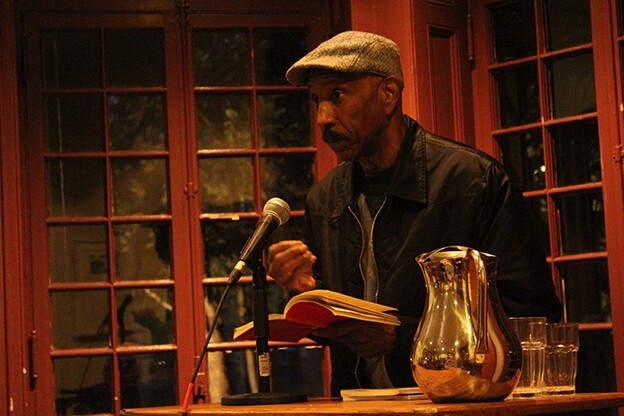

Will Alexander on Close Listening, October 19, 2016

Editorial note: Charles Bernstein and Will Alexander had a conversation about Alexander’s work for Clocktower Radio’s Close Listening at PennSound’s Carroll Garden Studios in Brooklyn, New York, on October 19, 2016. Some of the topics they touched on include: Alexander’s works, philosophy, connections and citations and references and sources, mythology, genre, aural properties of writing and performance, jazz, drawing and sketching, identity and politics of writing, location, and the writer’s mindset.

Will Alexander’s most recent books include The Combustion Cycle (Roof Books, 2021), Refractive Africa (New Directions, 2021), and The Contortionist Whispers (Action Books, 2021). He is the 2016 recipient of the Jackson Poetry Prize.

Charles Bernstein’s recent books are Topsy-Turvy (University of Chicago Press, 2021), Near/Miss (Chicago, 2019), and Pitch of Poetry (Chicago, 2016). More info at his commentary page.

This interview was transcribed by Gabriela Alvarado and lightly edited for publication. It can be listened to here. — Gabriela Alvarado

Charles Bernstein: Welcome to Close Listening, Clocktower Radio’s program of readings and conversations with poets, produced in collaboration with PennSound. My guest today is Will Alexander. Alexander is a poet and lifelong resident of Los Angeles. His first book was Vertical Rainbow Climber; it was published in 1987. I first saw his work when my friend Douglas Messerli published through Sun & Moon Press Asia & Haiti, a mind-blowing book, in 1995. Toward the Primeval Lightning Field was originally published by Leslie Scalapino’s great O Books in 1998 and was republished by Litmus Press here in Brooklyn in 2015. And that is an astounding book that I recommend you get. The storied and legendary City Lights published his Compression & Purity in 2011. Singing in Magnetic Hoofbeat: Essays, Prose, Texts, Interviews, and a Lecture 1991–2007, was published by Essay Press in 2012. You can hear many readings by Will Alexander at his PennSound page. My name is Charles Bernstein. Will, welcome to Close Listening.

Will Alexander: Thank you for having me.

Bernstein: So, what are you working on now?

Alexander: At present time, I have just completed a plethora of projects and am in the midst of a plethora of projects. One of which I’ll start in a random way, that’s The Secrets Prior to the Sun. It’s like a novella, velatura; it’s based on the condition of the Moriscos and Moriscas in Spain during the reign of Phillip II, but I turn it into a kind of poetic — a poetic chronicle. And there’s another one called Alien Weaving, which is a novella, which I’m pulling up here to show you at this time. But it’s called Alien Weaving, about the proto-mesmerizations of a poet-to-be, and her name is Kathrada. And my books start at strange points because I can be at any place at any time. I was scribbling some notes at a job when I started the Alien Weaving, and it began to, you know, proliferate from there.

Bernstein: How do you distinguish in your work between prose and poetry, novels, novellas, essays? In many ways, when you look at the work, it’s hard to sometimes say which is which. You’ve just handed me this book which I hadn’t seen, The Secrets Prior to the Sun, which is in prose format, and Alien Weaving, which is also prose format. What about the genre issue? Is that significant for you?

Alexander: The Secrets Prior to the Sun is a hybrid poetic work. It’s like Octavio Paz says in The Bow and the Lyre, you know: after the nineteenth century, these genres became fluid. And, for me, I’m in this river of poetry, so it tends to flow across genres. It’s like — it takes on a certain kind of a coloration, and it begins to move in a certain direction. So, certain things for me work as poetry, certain areas work as plays, certain areas work as essays, and certain areas work as aphorisms. It depends. As novels, as well. But it moves in that direction because it’s poetic — all my work is poetically based.

Bernstein: When you say “novels” — are there characters, plots, narratives?

Alexander: Absolutely. Absolutely. In fact, I may have one. It’s called Diary as Sin. That has been published by a small press in England. But all these works go as a piece.

Bernstein: How much of your work is published versus not published?

Alexander: Ooh. I’d say there’s a quarter of it — a good portion — that’s not published at the present time.

Bernstein: Going back to the ’90s? ’80s?

Alexander: Back to the ’90s. That’s when I — things began to really accrue. But for me, writing is like the way that wood was aged or the way wine is aged. Sometimes there are works that have been in the cooker for many years, such as the Alien Weaving, which was around the era of Asia & Haiti, but it just got published. And The Secrets Prior to the Sun was done recently, this year. So, there’s no sequential kind of circumstance.

Bernstein: Were you doing work before the first book in ’87?

Alexander: Absolutely I was doing work, but — I call it protowork — but one has to build up a certain kind of a stamina and a certain kind of a quality.

Bernstein: We’re talking about your twenties and your thirties ’cause we’re the same age.

Alexander: Yeah, yeah, but that would be —

Bernstein: So, tell me about that time.

Alexander: Internal combustion and initial — my initial alchemy.

Bernstein: Did you think of yourself as an artist, or were you more in the kind of protostage, as you’re saying, thinking and exploring?

Alexander: I was thinking and exploring and drawing.

Bernstein: Drawing? Tell me about that.

Alexander: I discovered that García Lorca drew, and at that time there was very little information about that that I could find, and I did come across some of his works in pencil, and that was enough to trigger me. Then I discovered the actual pencil drawings of Miró and it was enough to light the spark, and it’s continued to this day.

Bernstein: I would have thought that music was more a base than drawing in your work.

Alexander: Well, yeah, in that sense, music goes back to — actually, to the beginning. I mean, I was twelve, thirteen years old, fourteen years old, when I was instructed by Coltrane.

Bernstein: Instructed by Coltrane? You don’t mind if I dwell on that for a second.

Alexander: No, that’s fine.

Bernstein: I said — just riff off all you like, and that I wasn’t gonna pin you down on anything, but I got to ask more about that. Tell me that story.

Alexander: Well, I was, you know, I was always an inward person, never drawn to the exterior flamboyance, and in this particular situation, I was able to get into a riff with Coltrane. I heard —they had a great, great, great jazz station in Los Angeles, and there was like continuous music at a high level, and Andrew Hill, John Coltrane, Eric Dolphy, Charles Mingus, and —

Bernstein: So you heard all that stuff on the radio as a teenager?

Alexander: I heard all of that stuff, I absorbed it, and I absorbed the working methods, in a deep sense. You know, I’d listen to Jackie McLean, and I’d just hum it all day, you know. So, I actually grew up on Blue Note music, on New York music, in LA.

Bernstein: There are a lot of people who want to talk about a connection between jazz and poetry and you understand what that is. In your case, it just seems so — I almost wouldn’t want to have to ask you about what it is because it’s so apparent to me when I read your work, what the connection is to the music you’re talking about. It sort of sounds like it, the way it comes in, the way it goes out of tune, the way it extends, the way it ripples. A lot of the sonic textures seem deeply embedded in this early musical, or anyway, apprentice musical moment.

Alexander: Yeah. I was able, over time, to meet many, many, many players. Of course, Billy Higgins; I was able to spend time with Eric Dolphy’s parents, which I treasure; I saw all of his work before they put it into the public domain.

Bernstein: Did you ever play an instrument?

Alexander: I’ve taught myself how to play piano. I play it at present time, in spontaneous context. But I was always concerned with these sonic structures, these intuitive structures, coming out of all the great musicians. And I figured, if I listened to great music, somehow that rubs off on you, because it brings you to a certain level where you can appreciate that level in other mediums, you know. So when I was able to start reading books, that energy naturally translated to visual art and reading.

Bernstein: We’ve collected a lot of your work on PennSound, but I know you were interested in working with us to do that, so it seems connected to what you’re talking about. What is the relationship is of the performance of your work to musical performance, or what the difference between the performance and the reading and the writing is? How does performance work for you?

Alexander: Well, for me, performance is important: to read the work sonically. I always make this simplified distinction that my writing on the page is European, and my vocalization of it is African. So, therefore, I’ve seen so many performances of fabulous musicians, you know, not to just point out a bunch of names, but say like, Jackie McLean, Roy Haynes, Dannie Richmond. You absorb that kind of energy in your system. So when you get on to read or on stage or make a presentation, you become — I become very relaxed. I just become very, you know, spontaneous in my feelings. In fact, I just gave a reading last evening for the Jackson Prize, and it was just a comfortable evening, and to me reading is just like we’re talking now. It’s no different; it’s just maybe more individuals there.

Bernstein: But the musical values that you’re talking about do enter into the written text too. Even though you made that distinction — which I think was an interesting one and those of us interested in your work will go back to that point you just made — but still you’ve changed the prosody and the sense of extension that’s in the writing itself. One way I would say is that once one hears you — when I hear you read in person, or even just listening to the recordings, then that cues me to how to read the text.

Alexander: Absolutely, because for me, the aural property is the primal property, you know: not the optical property but the aural property.

Bernstein: You’re pulling at your ears, so you’re using the word I like very much: the A-U-R-A-L, the hearing.

Alexander: The hearing, the hearing, because this is, you know, in the Occident, it’s very open to the eye. It’s primary. Do you use the word — to quote Eastern psychology, it’s the aural. And for me, I’ve always heard before I could see, and that’s how I write my work. It comes to me —

Bernstein: So, for this reason I would think of your prose — although I understand what you’re saying about the genres — as opening up to waves of sound and the kind of overlayed jazz of Coltrane and company that you listen to. And the prose allows for that kind of overlay, and also for a kind of tenor saxophone sound, even more than voice or voicings, because there are multiple to emerge through that prose. Harder to do with lines; lines tend to take away from some of that density. Does that make sense?

Alexander: Well, it’s waves of sound for me. And for some reason my sentences are instinctive. I know when they stop, I know when they start, and how they work. One-line sentences or long extended sentences. It’s not problematical for me, but it’s an instinctive understanding of when things start and when they stop, inside of a mega-flow.

Bernstein: Can you talk about how you write? When you’re performing your work, you’re reading material as a script, so it’s written down. Is there a particular way that your writing comes into being? Is it revised? Is it spontaneous?

Alexander: It is, it comes from an aural spark; like Miró says, there’s a speck on a canvas, and I go from there. And I hear a sound — it could be a particle, almost a phoneme, and I can just go from there. And against a track —

Bernstein: So, it’s improvisatory.

Alexander: It’s improvisatory.

Bernstein: And do you revise after you’ve written this?

Alexander: Yeah, I’ll say that. I call it a different level of hearing. And so, what I do is I put the work in a position where it works, and then I put it away. I let it set, I let it set. And then I come back to it when it has grown, and I have grown, and I look at it and something else will speak to me. And, as I’ve gone on with my praxis, that process is quicker and quicker.

Bernstein: How about voice in your work, or voices? I would say your work is possessed by multiple voices. But how do you see that in terms of your own voice or voicings pushing back against a whole lot of material that you’re moving through? Like a person weaving through a dense crowd, for example, or even in moving through a forest — how do you see the relation of particularizations of your voice or your authorship versus the channeling of voices from the outside that seem to possess your work?

Alexander: Well, as earlier you stated, it is a spontaneous revelation, and when I’m working with — say, for instance, I’m working in the form of plays, a sound will come to me, and out of that sound, for some reason, characters begin to accrue. And these voices start playing out against one another. And, in fact, I thought I would never write a play, and one evening I was just sitting, and a sound came to me. And another sound came to me, and I said, that’s somebody speaking to me. And it was a character speaking to me, and I began to — as I wrote it down, another character appeared. And then another character appeared. And then they began to circulate and circle around one another, and they began to form these clusters and these densities and these separations and these partial acclimations to one another, and the play began to form in that point. And that’s something I’ve — that’s one part I’ve not done as much of, in terms of playwriting. Although I’ve done quite a few of those now; at least about, oh, about ten or a dozen plays.

Bernstein: Have you seen the work done with other people reading the different sections, as opposed to …

Alexander: Oh yeah, yeah, yeah.

Bernstein: How do you feel about that?

Alexander: It actually worked out well. We did a walk-through. I did a play called Combustion in the Catacombs. It’s set in an asylum in New Mexico with two female characters, and they’re both completely mad. Cortaenia and Eurydice. I remember the two characters. It’s a two-hander. And then there was another two-hander entitled Inside the Earthquake Palace. It’s a book of plays of mine. That’s the title piece, and it’s about two male photographers: one an apprentice, and one an accomplished master on the edge of extinction in Plymouth, before the volcano in Montserrat. So that’s how that was set.

Bernstein: Your work is filled with is multiple and mythopoetic sources. Now I say mythopoetic because it has a history as a term. How do you think about the sources of your work? I mean, that’s certainly a distinct aspect of your work compared to most of your contemporaries. And it relates to a whole — a range of mythopoetic writers that you’re not really similar to. It strikes me that you do “mythopoetics” in a very different way, which encompasses references to scientific material, mythological material, and historical material. Your poetry is dense with references. Where do they come from? Your work has an encyclopedic aspect in that way, but it’s never — it’s never regulative, it’s never prescriptive, and if you follow up, as I sometimes do, and read closely, it takes you to very specific places. Gods that are mentioned have a specific relationship to what you’re talking about. Yet it’s not religious.

Alexander: No.

Bernstein: So, talk to me about your sources. Where do they come from, what is your sense of how they work in your poems?

Alexander: Well, as Lorca once said, you know he talked of the region from which he evolved in Granada, and I have that instinctive sensibility of these areas. I myself don’t know how it comes about, but it’s very accurate, and I trust it. And I’m very voracious in terms of my interests.

Bernstein: Well, you must be reading a lot of the material for these, because they’re not made up.

Alexander: I do. No, no.

Bernstein: You use the term “fiction” and all the rest, but it’s more within a mythopoetic context in which the names that are mentioned — while they’re not in orthodox Western literature, they’re deeply heterodox and they’re meant to be. And they’re from a very different space; and also there are scientific, as well as imaginary, characters. But they are specific, they’re not made up by you.

Alexander: No, no, no, I don’t make up anything in terms of — once in a while I’ll make up a word in terms of my flow.

Bernstein: I’m not talking about words. I am speaking of the proper names and the references in your work.

Alexander: The proper names are real, and they’re concrete, and I do a lot of work. As I tell students periodically when I do instruct: get great dictionaries, and have a ton of interest. And it hones your instincts as to that book, versus that book, versus that book. I mean there’s a difference between people who say they read eclectically, but you have to read — when I’m doing a project, I kind of start reading in that direction.

Bernstein: Eclectic is a word that could be used, but I resist because I would say you’re a visionary poet, so it’s more like Blake, his prophetic books. Though Blake, of course, did make up (create) his characters. Now, I’m eclectic — creating by hodge-podge, picking this and that for a variety of reasons and with different registers. It strikes me that your names are more like constellations in the sky.

Alexander: I was about to say that.

Bernstein: They make connections that actually are vivid and embodied, if you can follow the historical and mythological associations.

Alexander: It’s interesting you should say the word “constellations” because they are constellations. You know, if I’m reading Sri Aurobindo, I’ve been greatly influenced by his philosophies, and Gurdjieff, there’s André Breton, and you find constellations because Gurdjieff — and Breton loved Gurdjieff, and I didn’t know that until not far back. And you know all these things do connect, and I’m concerned not only with the — trying to say too much at once — but not only the subconscious but what they call in the East the supraconscious mind. Above the Human Nerve Domain is one of the titles of my books. So in other words, it creates a voraciousness and a kind of a mindset, the supramind, that is electric and able to work with things at a level that is nonpalpable as such.

Bernstein: Do you feel that readers or listeners enter into that?

Alexander: Yeah, I think —

Bernstein: Based on their experiencing your work?

Alexander: Yeah, it’s a space that one doesn’t have to … it’s so far beyond a grounded geography and a sequential sense. It becomes hypnotic, in that sense, and that drone that I got from Eric Dolphy and John Coltrane because actually I skip around. But I learned talking about genres, Eric Dolphy inspired my ability to — like he changed horns — I change with the same thing in mind.

Bernstein: Well … Sun Ra, a Philadelphia native as he is, we’re not in Philadelphia, but still PennSound, so you will be. Sun Ra comes to mind in terms of the cosmology of the specific interest in that.

Alexander: That, and particularly yes, Sun Ra and as I said Aurobindo, and it goes on, you know, Gurdjieff, essays by Coomaraswamy.

Bernstein: You often speak of and are associated with Aimé Césaire. Maybe this is a good moment to think of him as a — in terms of your work, do you think of him as an influence, a precursor figure, or rather someone you’re interested in as a poet and find compelling?

Alexander: For me he’s all of those things. He’s a precursor figure, and like Breton and Césaire; they open the doors at different levels for me. Because Breton gives you the okay to write — and I’m not saying this in a doctrinaire sense — but the idea of opening up with no mistakes. One can flow — one doesn’t have a sword of Damocles hanging over one’s head about what should be done and what shouldn’t be done. All is allowed. And then Césaire for me, bringing the situation of the colonial situation, the way the world has gone for the past five, six, seven hundred years, and being a Black person, I’m following that same reality. And he used French, I use English. And it’s a factor of liberation. In fact, here’s a quote here we can take a look at from another book, Spectral Hieroglyphics. It’s three poems: one on Césaire, one on Artaud, and one on Lecomte. And I have a quote in the back here. It says, “I argue that American English is not a European or White language; it’s a miscegenated language because of our linguistic contributions and inventiveness. I’m concerned with using language like Césaire to turn the world upside down. Writing a foreign language within your own language creates another language.”

Bernstein: Exactly my view about that. I completely agree with that view about English, American English, as being fundamentally miscegenated. And that has a lot of political implications, of course for our current election, very obviously, but in other ways. Do you think of your work as political, and in what sense is it political? What about it is political?

Alexander: Well, for —

Bernstein: You’ve already put it forward in the colonial context in a political way, but how does it work as politics?

Alexander: Well, the fact is that anything that a person of color does in this kind of general context becomes a spark, some kind of political activity, just by the nature of the circumstance. It’s like striking a match in an atmosphere of gasoline — something’s going to flare up. And so this is the context we’re in, and I go back to the beginning of the colonization of the Portuguese to the present time. It’s been a nightmare for my side of the equation, and Césaire says, well, here’s a way to liberate one’s internal space. So, if I liberate my internal space linguistically, I can begin to liberate others as soon as they pick up the book. It’s like actually putting the book out there on the waves, like the bottle: you let it flow up to another shore. And whoever picks it up grabs the magic. Or internalizes the magic, I should say. So this is the way I look at it: it’s not political in an overt sense, but a person has a — a person of color has a responsibility now to begin to extend himself or herself out to the great diaspora.

Bernstein: You bring up questions of identity. What are your senses of how identity works in your poetry or for you? I mean, what is your relation, for example, to Los Angeles? Do you feel yourself to be a poet from Los Angeles?

Alexander: No. I’m not a Los Angeles patriot. [laughter] That’s why I’m in New York. But I’m not here, you know —

Bernstein: You’re a sojourner.

Alexander: Yeah, I’m not a localized to Los Angeles. In fact …

Bernstein: Well, that’s what I mean. Maybe I’ll just go with that. I’m interested in the way in which your work is so particularized, but the located space isn’t the way we conventionally think of location.

Alexander: Yeah, it’s not location in that sense because, for me, I’ve always just needed a large city with cultural resources. And Los Angeles does supply that up to a point, and it’s an amazing place. But I can’t be a patriot of a certain region because I’m comfortable if I write in New Mexico, or if its Berlin, or Lisbon, it doesn’t matter. New York. But I’m that self that can operate in pretty much any locale.

Bernstein: But do you feel like your work expresses a self that exists before it? Or rather that something else happens in the work that’s different than your everyday self, the person who walks down the street and buys a cup of coffee?

Alexander: I don’t feel that — yeah, for me, it’s gotten to this state where for me language is yoga. And so the person that walks down the street and the person that writes is simultaneous at this point. You know, but it is a yoga, and it is an alchemy of living for me. Language has created in me this alchemy of living. So I’m always looking to expand and expand and expand. Not to just improve, but to expand consciousness via language.

Bernstein: You have been listening to a conversation with Will Alexander on Clocktower Radio. Close Listening is produced in collaboration with PennSound. The program was recorded on October 19, 2016 in PennSound’s Carroll Garden Studios in the free state of Brooklyn. My name is Charles Bernstein, close listener to the cosmic spaces inside the cosmic spaces.