Someone’s got to keep this generation honest

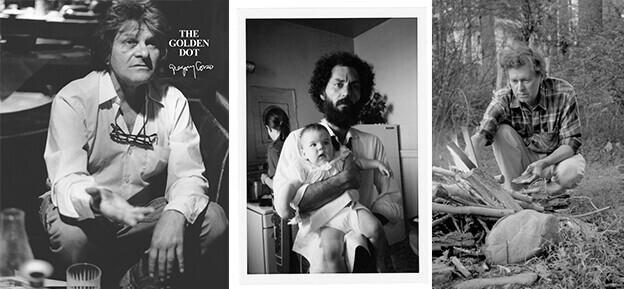

Corso editors Raymond Foye and George Scrivani, with William Lessard

Note: The youngest foundational Beat is having a revival. After a folio of new poems appeared a few months ago in The Brooklyn Rail, the full collection from which they were excerpted has arrived, and it couldn’t be more of a surprise — and a delight.

The Golden Dot: Last Poems, 1997–2000 (Lithic Press, 2022) is a white-hot summation and extended last word of a poet who was most alone in the company of others and frequently his own worst advocate. The Shelley-infused lyricist, familiar to us from more than a dozen books across forty years, is still in evidence, but there is a newfound clarity and urgency to the work, which is like meeting a long-lost friend after decades apart.

It was my pleasure to interview longtime Corso compatriots and editors Raymond Foye and George Scrivani, who have accomplished the heroic task of transforming the fluid manuscript Corso left into the poignant collection we have here. Like many folks from New York City’s poetry community, I knew Corso had a final great book in him, but I doubted the unrepentant hellraiser would ever pull it off.

To hear Foye and Scrivani explain it, Allen Ginsberg’s death in 1997 and Corso’s own approaching demise in 2001 were the catalysts. Following is our exchange, which took place via email somewhere between Greece and the Hudson Valley. — William Lessard

William Lessard: For anyone who is coming back to Corso after reading him a while ago or experiencing him for the first time, what would you say are the biggest misconceptions about him and his work?

George Scrivani: Just the whole mythology of him as the bad boy of poetry, the enfant terrible. Gregory never wrote poetry about his mythology; the mythology was to help him get through the day or to get through the poetry reading. It had nothing to do with those moments when inspiration struck. The myths and stories about Gregory get in the way of appreciating his work.

Raymond Foye: The mythology was part of the man — he was a mythic figure. He was playing with archetypes and enduring ideas within the grand sweep of history. When you met Gregory, it was like meeting Keats or Byron: he was a poetical force of nature. Having acknowledged that, I would say in the end, the only thing one should trust is his work.

Lessard: You’re talking about received notions about the Beats. Do you think the term is still useful?

Foye: For me, the term “Beat Generation” meant quite a lot in its inception. When Ginsberg and Kerouac meet Herbert Huncke on Forty-Second Street in 1948 and he uses the word “beat,” a light goes off in their heads. This was a new sensibility and a new vocabulary to go along with it. Today it may be too broad a term to mean anything outside the historical context. But it was a great label, like Abstract Expressionism — which means quite a lot when applied to a de Kooning from 1953 but practically nothing when applied to a de Kooning from 1986. Stylistically they all outgrew the phrase.

Scrivani: Beat was about a new consciousness, a new way of looking at life. Gregory more than any of them fit the bill of the Beat Generation writer. He lived the spirit in ways truer than any of the other ones, but Gregory himself didn’t like the constraints of the term. He had an on-again, off-again relationship with the term: he either liked it or hated it depending on the day. The problem is the mass media jumped on the Beats from day one and tried to make a caricature of them, largely to undercut their message. If the reader is still going to buy into the stereotyped notions about the Beat Generation, it’s going to keep them from doing the reading they need to do to understand what these people were thinking and feeling.

Foye: My definition of Beat is broad. I would include Joanne Kyger, Diane DiPrima, Amiri Baraka, John Wieners, Bob Kaufman, Philip Whalen … all remarkable writers. There are many more. We are now at an interesting stage with the Beats where a lot of ancillary writings are coming out. Importantly, I would point to Allen Ginsberg’s Deliberate Prose: Selected Essays 1952–1995 and his Spontaneous Mind: Selected Interviews, 1958–1996 — both are essential. Jack Kerouac’s Some of the Dharma is the best guide to the “spiritual” side of the Beats; I think it’s an extraordinary book. I would also recommend Preserving Fire: Selected Prose by Philip Lamantia and There You Are: Interviews, Journals, and Ephemera by Joanne Kyger and all of Amiri Baraka’s prose. Many of the poetics classes from Naropa Institute are online at archive.org — that’s an essential resource. I don’t know any other group of writers who have left such clear instructions to young people about how to negotiate the perils of power, political propaganda, and media brainwashing. I wouldn’t much bother with the biographies.

Lessard: In your introduction, you write about Corso’s public persona as a jester. You explain it as a way of protecting himself from other people but also himself. I agree with you one hundred percent, having seen Corso in action. To me, it was all about the shame he felt about his early life.

Foye: Is it shame, or is it the very natural sensitivity that comes from having to expose your deepest feelings in public? The poet is naked in that respect, far more than a painter or a musician, who can still hide behind their paintings or their instruments. When you saw Gregory read his poetry in public, you saw the raw nerve. The tragedy of his childhood is always there, but I don’t know if shame is the right word. Actually, I think he overcame that shame. At a certain point he realized he had to move past that, and he did. Not to say that it ever goes away. You do not get over your mother and father.

Lessard: It’s striking how precarious his life was all the way through. Today, many writers are academics. But Corso was an unrepentant old-school bohemian, and he often paid the price for that freedom.

Foye: That is certainly true. He never compromised his values, ever. Think about his refusal to sign the loyalty oath upon arrival at SUNY Buffalo in 1965 and being dismissed on the spot when he was about to begin a very comfortable job in academia.

Scrivani: I remember when Allen Ginsberg offered to nominate Gregory for the American Academy of Arts and Letters. He said, “No, not me. I’d rather not be part of this. Somebody has to stay outside the Academy and keep this generation honest.”

Lessard: The poems in this book are both familiar and strange. Corso’s voice is unmistakable, but I feel like I am discovering a totally new poet. Was that your reaction when you first read this manuscript?

Foye: Yes, absolutely. His honesty amazed me. I once said to Gregory, unkindly, “It’s always special pleading with you.” Drug addicts and alcoholics have a lot of excuses. There are no excuses in the late work. It’s a philosophical and karmic reckoning, and it’s total. Also, the level of skill amazed me, technically speaking, although I suspect many won’t see that.

Scrivani: I felt like I was discovering a totally new poet. This was a new voice for Gregory, but it isn’t not Gregory. You can recognize Gregory in his last book just as much as in the first one, but there’s a clarity of address. He’s hell-bent on making the situation clear and dispensing with the verbal pyrotechnics and the rhetorical flourishes he once reveled in. He keeps some of them, but he’s using them very sparingly because he has a point he wants to make. Either he wants to clear up a misconception or make a confession. We all knew the public Gregory as an arrogant fucker, but he wants to tell you that that is not who he is.

Lessard: In one of the finest moments in this collection, Corso writes, “What I don’t know / I know well.” People make a lot of his Buddhism, but he seems like a Catholic to me — or Christ surrendering to the inevitable.

Foye: He’s Catholic and Buddhist. He says in The Golden Dot that he accepts Christ and Buddha as his teachers. His Buddhism is the Zen of the koan: “What I don’t know / I know well.” That’s about dwelling in the mystery. But I really don’t think theology was important to him in any significant way.

Scrivani: Gregory accepted the Buddha. But as a person, he was branded with the Catholic nightmare. The indoctrination of children by the Catholic Church — particularly the pre-Vatican Council church — was terrifying and absolute, and his relationship with Catholicism was conflicted and antagonistic. Which is not true of his relationship with the Buddha: his relationship with Buddha was not ambiguous. He had a Buddha in his mind, and he liked the Buddha that he had in his mind, and he took it with him to the very end.

Lessard: Many of the poems are about saying things left unsaid with friends, lovers, and other people in his life, from Ginsberg on down. That many of the people he knew were no longer around seems to have freed him up.

Foye: Yes, there’s this feeling that he’s been going through life blindly, striking out at everyone and everything, and now there’s a new piercing clarity and focus to his life. Throughout this book, I kept thinking of Allen Ginsberg’s line to his mother in Kaddish: “Now I’ve got to cut through to talk to you as I didn’t when you had a mouth.” What’s remarkable is that he was given the time to write this book. He had three and a half years in this modality of Death; Allen only had two months, at the most.

Scrivani: Old friends and lovers populate this book, but mostly he is writing to himself and the reader. In The Golden Dot, he’s looking for the original connection; he’s coming full circle. Other aspects of being a poet took the lead in the glory days of his youth, but now he’s come to this wizened old understanding, and he wants to set down in the poems all the things that came out of being a poet. The message, the communication, is what it’s all about. It’s about him connecting with the reader. And: Can he do it? He’s put everything in his life through the grinder, and there’s not much left, but the song is still there. And it’s very simple and sometimes sad but often exalted, and it’s about a few things that he’s come to understand about the life that he’s lived. He evolves from the lyricism of his youth into basically a pre-Socratic philosopher. And if you look back on those pre-Socratic philosophers and Socrates himself, they were all poets who then turned to philosophy — and that’s what happened to Gregory. Gregory understood there was a natural progression there: if you stay alive long enough, you’re going to become more philosophical. So then, it became: “OK, what is the wisdom that I have to impart?” And that becomes the subject of the last book. He becomes a part of wisdom literature. During the time I hung out with him, I felt like this guy was pure gold, and nobody could see it. He was not recognized; all people saw, if they saw anything, was the problematic person, not the truth or the poetry or the pure gold that was there. Thus, the golden dot at the end.

Lessard: My understanding is that this manuscript was still in a fluid form when he died. How much work did it take to get it into what we have now?

Foye: It was far from a clean manuscript, but on the other hand we were not altering the poems in any way. We were going through the manuscript poem by poem and trying to get at the essence of what he was saying, trying to allow enough repetitions for the themes to cycle back without it being tedious. As an editor, you are not just thinking about individual poems; the book itself must have a form. It was clear he was struggling with the book, although it was full of gems. There was a fair amount of deciphering because pages were torn or stuck together. In some cases, his typewriter ribbon ran out, but he continued to type, so the lines appeared to be blank. I took a soft lead pencil and gently rubbed it across the surface of the paper, and those lines suddenly appeared because the typewriter keys were striking the paper and making a faint impression. Some important poems were recovered in that way.

Scrivani: We worked toward letting the manuscript have a voice. That dictated how we edited it. We worked to free the manuscript of the confusions while leaving the imperfections to the reader’s discretion.

Foye: I had a working friendship with Gregory more than twenty years as editor and publisher, and George was with him for over thirty years as best friend and translator and editor. We both helped him prepare manuscripts for publishers, so we had firsthand knowledge of his editorial process. There were plenty of times where we had to stop and think, what would Gregory do in this instance? We were evoking him, channeling him, having arguments, and playing out the discussions. We were asking him to answer the questions we had. And I know we both had some very intense dreams of him during this period — not to get too weird about it.

Scrivani: I felt closer to Gregory during our work on that book than I had since his death.

Foye: More than in his lifetime even, in many ways. Because this was a Gregory we hadn’t seen — or had rarely seen. And it’s the true Gregory.

Scrivani: That manuscript brings the presence of the man and the whole complex of what he was into palpable form. It’s hard to fathom the meaning of another person, especially his person. I feel like he went a long way toward helping us try to do that.

Foye: What was interesting was the fact that the manuscript came into our hands not the year he died but twenty years later. His friend Irvyne Richards kept it locked up. Then suddenly it appeared when we’re in the middle of a pandemic, and the life-and-death nature of what was taking place outside in the world lent a real drama to what we were doing in private. It made it seem like the most important thing in the world at that point for both of us.

Scrivani: [Laughs] It certainly did. I haven’t quite gotten over that feeling. It was exhilarating, and hopefully soon we’re going to see this thing, unless there’s a new plague or a new war.

Lessard: What has been the reaction to the book so far? The selection of poems in the Brooklyn Rail a few months ago and their “New Social Environment” Zoomcast really seems to have jump-started a revival of Corso’s work.

Scrivani: For me, the great thing was how the young ones are all getting it. It seems like they are looking at the poems for what they are. They’re free of the Beat thing in a way.

Lessard: Where would you place Corso within the tradition? Between Shelley, Catullus, and his countless other influences, it’s no secret where he placed himself.

Foye: He never claimed to be on that level, but that’s what he aspired to: Shelley, Vermeer, Mozart, Emily Dickinson — pure spirit.

Scrivani: Gregory’s poetry is about the weird, and it’s about the true, and it’s about the beautiful on the simplest plane imaginable. That’s what I am seeing of what he accomplished in the last book.