The longer short of it

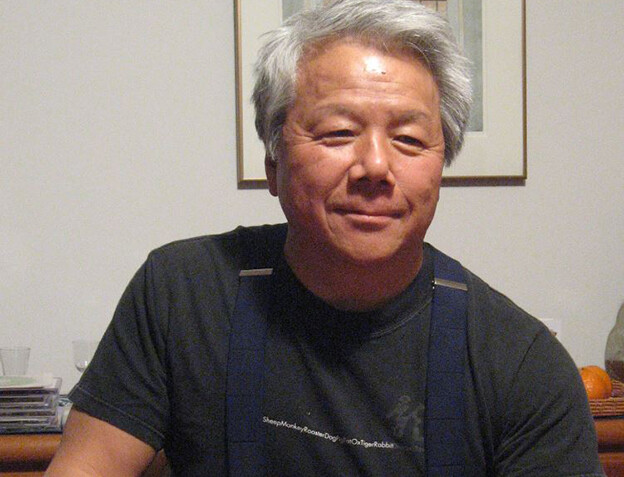

An interview with Hiroaki Sato

Note: In early 2020, Eve Luckring (writer and visual artist) and Scott Metz (poet and editor) began a lengthy email conversation with essayist and award-winning translator Hiroaki Sato. A New York City resident since moving to the US in 1968, Sato has translated more than thirty books of Japanese literature into English, authored several books on Japanese cultural history and poetry, and translated the likes of John Ashbery, Jerome Rothenberg, and Charles Reznikoff into the Japanese language. The poet Gary Snyder has called him “the finest translator of contemporary Japanese poetry into American English.” Sato is well-known for his one-line translations of haiku, which in his own words is “an exceedingly unpopular view among academics.” It is a decision based on his prodigious knowledge of Japanese poetry’s long history and formal evolution, one significantly informed by his persistent efforts to translate beyond the familiar premodern classics and introduce English-language readers to mid-twentieth-century poets, including those who experimented substantially with traditional forms. The following interview has been condensed and edited for clarity. — Eve Luckring

Eve Luckring: You studied with the poet Lindley Williams Hubbell at Doshisha University in Kyoto and met your American sponsor, the art historian Rand Castile, at an art performance by James Lee Byars. Can you talk a bit about how your early experiences studying Western literature and being exposed to the likes of Byars influenced your decision to move to the US in 1968?

Hiroaki Sato: I chose the English department of Doshisha University because, well, English was the only subject I was good at in high school and because I had flunked the entrance examination for my first choice, Osaka University of Foreign Studies, a year earlier. In the interim, I attended Kitakyūshū University of Foreign Studies in Kokura instead of choosing to be a ronin — as you know, that’s what one is called when you flunk the entrance exams for your target university — because it was close enough to where I lived for me to commute every day.

Now, for those of us who grew up during the Occupation (that ended in 1952 when I was ten) and for some years that followed, studying English was a must; it became a required subject in the first year of middle school, which means when you turn twelve. In fact, we started learning the Roman alphabet at the start of primary school. I do not object to that idea! It was a great excitement to me to begin to learn English.

It was by accident that I met James Lee Byars on the streets near Doshisha, or so I recalled later when the museum curator Sakagami Shinobu asked me how I got to know him when she was writing a book, James Lee Byars: Days in Japan. I tried to remember how, and thought that one of the upper-class women students at graduate school may have suggested to Lindley Williams Hubbell that he tell Byars about me — to invite me to his upcoming show. At the time I didn’t know anything about it, but Hubbell was a good friend of Byars. Otherwise, as my vague rationalization tells me, Byars couldn’t have given me one of the paper artworks — made of expensive washi — he was carrying under his arms and invite me to his show just because he came across me on the street.

At the show, I met Rand Castile, who was studying cha-no-yu, tea ceremony, at Urasenke under a Fulbright scholarship. And it was Rand (and his wife Sondra) who invited me to New York the next year.

New York City wasn’t the first American city I visited. It was Redondo Beach, LA, and it was 1966. At the time it was an idyllic town by the beach. That came about because of another American poet teaching at Doshisha, Edith Shiffert. She said that her sister, Alice Boaz, would take care [of] me for two months if I paid the airfare. So, I asked my parents, and they said yes. My family was typical middle class. (In those days, the Japanese government, newspapers, and TV programs all insisted that Japan was a middle-class society.) Later, it occurred to me that this had strained my mother’s monthly budget.

In retrospect I realized it was in the spring a year earlier that this country had started bombing North Vietnam. I was utterly apolitical at the time, although, of course, there is the question: If I were political, would I have declined Mrs. Shiffert’s kindly offer?

Luckring: Yes, it’s fascinating how the very decisions that so strongly affect our life trajectories often come from a perspective we no longer inhabit.

When you later returned to the US on a longer visa/sponsorship by the Castiles, what was it that influenced you to stay here?

Sato: I stayed on because, after a year during which I was totally dependent on the Castiles, I was about to go back to Japan when Sondra found an opening at an organization called the Japan Trade Center. The trade agency promptly employed me because a young Japanese employee was quitting. In those days, tourist visas and other things were a lot more relaxed. For example, on a tourist visa, you could stay here for eighteen months by extending your visa twice — doing so required you to go out of the country and come back. The first time, I remember Sondra driving me out of Eastport, Maine, to cross over to Canada and coming back a few minutes later. Eastport was where her parents had a large house.

Rand and Sondra, with their two daughters, were far from well-to-do, though both taught at St. Thomas Choir School. They were exceptionally kind and generous, even persuading their friend, Jorge Perez, to share his small apartment with me. Jorge, in turn, was kind too. He split his small apartment into two sections and let me occupy one of them.

It was only after some years later that I learned about President Lyndon Johnson’s great Immigration Act of 1965 that would alter the population composition of the United States. And that was only three years before I came here!

Luckring: How did your writing career develop? Was translation always a primary interest of yours?

Sato: I started translating after I was employed by the Japan Trade Center and began to live in my own apartment, a studio. My pay was small (I am sure it was average for someone in my position, American or Japanese), so initially I did translation for money. The first time my friend accompanied me to a supermarket nearby, she filled the cart and I was surprised to pay only twenty dollars! The first typewriter I bought here was a small (in my memory) Underwood. I did so much work on it … and it was such a darling machine!

One of the first things I translated were handwritten letters a Japanese fishing company in Peru sent to its parent company in Japan. Another thing I translated for money was Alvin Toffler’s Future Shock. I also translated patent applications. I quit doing so when I was assigned one on an improvement to the design of a nuclear power reactor. My knowledge of science was (still is) so limited that I am sure many applications were turned down because of my mistranslations.

At the same time, I started translating literary stuff. The first one I worked on, I’m sure, was love poems of the sculptor-poet Takamura Kōtarō (1883–1956), the work I had started with Sondra Castile back in Kyoto. Years later, it occurred to me that any Japanese male who starts translating Japanese poems with an American or English female would pick Kōtarō’s love poems for his wife, Chieko (Chieko shō). Chieko was one of the New Women in the 1910s, but she suffered from schizophrenia and died in 1938. I did not change a word of my translations with Sondra, even when I had occasion to revise them later, to commemorate our work together. The first edition came out as Chieko, and Other Poems of Takamura Kōtarō from the University Press of Hawaii in 1980.

Luckring: You told me once that you considered Persona: A Biography of Yukio Mishima (Stone Bridge Press, 2013) your “lifework.” What about it became so meaningful to you?

Sato: It was the book in which I was able to describe someone almost as fully as I wished or could.

When I started to translate Inose Naoki’s Perusona: Mishima Yukio Den at his request, it didn’t take me any time to see it was terribly deficient as a biography. So, I decided to add a lot of historical background and Mishima’s personal background, etc. History, because I had neglected to learn much of anything from the period that was important to him — his grandparents’ days from Meiji (1868–1912) to Taishō (1912–1926) and the period of his youth both before and after Japan’s defeat in 1945. I spent a dozen years on the man — more than thirty years if I include the time I worked on Mishima’s plays and a novel, Silk and Insight.

Luckring: Mishima is well-known for his embrace of modern Western literary styles. What, in your opinion, are some of the most important ways Western poetry has influenced Japanese poetry since the Meiji period into the twenty-first century?

Sato: What impressed the Japanese most about Western (English) poetry was its length and the breadth of subject matter that Westerners covered in their poems. This was evident when, in 1882, three men got together, translated a dozen English poems into Japanese, wrote six original poems (in Japanese), and published a book, Shintaishi-shō (A Selection of New-Style Verse), to tell their readers to write poems in “modern” (current) Japanese. The poems they chose for translation were “The Soldiers Home” by Robert Bloomfield, “Ye Mariners of English, A Naval Ode” by Thomas Campbell, “The Charge of the Light Brigade” by Alfred Tennyson, “Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard” by Thomas Gray, and so forth.

Anyway, the three men who did the first anthology of translations of English poems derided tanka and haiku — actually, one of them talked about tanka and senryū[1] rather than hokku[2] — as comparable to “incense-stick sparklers” and “shooting stars” (yobaiboshi) in regard to the amount of “thought” that could be sustained in the lengths of these forms.

Luckring: What about Western influences on traditional poetic forms?

Sato: Generally, “Western influences” on haiku and tanka go back to the Meiji Era when people began to mention trams, densha 電車 and trains, kisha 汽車. Is doing so permissible, was the question, I think.

Since I mentioned Takamura Kōtarō, I should say that the initial slogan for Westernization (“civilization and enlightenment”) provoked a counterattack, as it were. Nationalism came back; the idea at the time was to find worthy things in things Japanese. One result was the art school (the predecessor of today’s Tokyo University of the Arts) that Ernest Fenollosa and Okakura Tenshin founded in 1887, [which] aimed to emphasize traditional Japanese art.[3]

Then, theoretically, there was Shiki’s talk about shasei 写生 (“sketch from life”), followed later by Seisensui’s talk of German philosophy. Then the deluge, as Lindley Hubbell used to say.

Luckring: Yes, I don’t know how many people realize that the common definition of haiku, at least in the US and England, is indebted in part to Western notions of realism, which were deeply influential to Shiki’s reform efforts during Meiji. And from there, modern haiku expanded out into a variety of directions, not widely recognized outside of Japan. What about Western influences on twenty-first-century Japanese haiku and tanka?

Sato: I am not as up-to-date on this century, except for my friend, tanka poet Ishii Tatsuhiko. Generally, it is hard to pinpoint Western influences, except for the general atmosphere.

The haiku poet Tanaka Ami, for example, is a student of German literature, especially modern German poetry, and I see several dozen haiku of hers on the website of Modern Haiku Association. But it will be hard to discern any Western influences, let alone German influences, in any of them — and that’s apart from the fact that I know little of German literature, let alone German poetry. Take this one, which tops her selection here:

潮騒で終はるシネマや花曇

Shiosai de owaru shinema ya hanagumori

Cinema ending with the sound of waves: flowery cloudiness

Anyhow, hanagumori, here given in a terrible translation, “flowery cloudiness,” is an old kigo dating from Bashō’s days.[4] The word is said to come from the Chinese expression 養花天, “flower-nurturing sky,” that is, cloudiness about the time when flowers grow. As far as I can tell from the selection, it seems that Tanaka combines old traditional kigo with delicate observations.

Before I forget, I should mention that one of the dozen haiku books Natsuishi Bany’a, a professor of French comparative literature at Meiji University, gave me while we were friends, as it were, was A Guide to Haiku for the 21st Century (Gendai Haiku Kyōkai, 1998), an anthology that includes haiku writers from various foreign countries. (It includes my translations of Janice Bostok and Chris Gordon.) I had forgotten about this, but now taking it out from the bookcase, I see there is, for example, Nakagarasu Kenji (1948–2014), apparently a gay man, with his haiku not adhering to teikei (the fixed form of five-seven-five syllables):

ボン・ジョヴィめく追憶の空に梅花が濁るか

Bon Jovi-like meku tuioku no sora ni baika ga nigokuruka

In the sky of Bon Jovi-suggestive memories plum blossoms murky

愉快な女優(クウィーン) D .ホックニー的水しぶき

Yukaina queen D. Hockney-teki mizu-shibuki

Gayeous queen D. Hockney-like splash of water

開いたファスナー。R.メイプルソープの泡立ち

Hiraika fasunā. R. Mapplethorpe no awadachi

Open fastener. R. Mapplethorpe’s foam

Luckring: You’ve often mentioned your appreciation of Burton Watson’s approach to translation. What other translators of Japanese poetry into English do you especially appreciate?

Sato: This is at once easy and tough to respond to. Easy to answer because Burt made every translation easy to understand, easy to read. That’s partly because he chose to translate things that were easy to understand while ignoring what could be difficult in the original (or in translation). Burt wrote that he was enlightened when he started reading the Beats. That makes his translations of classical Chinese poems read like hippie poems, some have complained.

On the other hand, it’s tough to answer your question: I translate sometimes because I don’t like other people’s translations. I showed this first when I compiled more than a hundred translations of Bashō’s “old pond / frog”: One Hundred Frogs: From Renga to Haiku to English and also in the introduction to Bashō’s Narrow Road: Spring and Autumn Passage.

I usually do not read other people’s translations except when I need to compare how different translators have worked out the same thing. In this regard, The Tale of Genji may be an exception because when Arthur Waley’s translation came out, the writer and literary critic Masamune Hakuchō (1879–1962) famously reported he was happy with Waley’s English translation because he found the original too murky, too difficult to understand.

Then, when Seidenticker’s translation came out, my informal English teacher and friend, Eleanor Wolff, was indignant that the new translation wiped away all the atmosphere of the aristocratic society that Waley engendered in his translation. On the other hand, my Genji scholar friend, Doris Bargen, says Seidensticker’s translation is the best as a classroom textbook because, aside from Waley, the newer translation by Royall Tyler is impossible to use as a textbook. I wouldn’t dare translate Genji, but I wrote a review.

Luckring: I really appreciate how you contextualize those three translations with Yosano’s and Tanazaki’s in your review — it speaks to more of the cross-cultural issues you’ve briefly mentioned.

Sato: Other than translations of Japanese, which translation is better than the others is an endlessly fascinating subject. I have half a dozen translations of Homer, from Alexander Pope’s to those by translators a few decades ago (though not the more recent ones). I, of course, do not know a thing about Greek, ancient or modern, but when I read Pope, I can’t believe that the original Greek could be so slick and felicitous, while I imagine that Richmond Lattimore’s crusty translation might be the closest to the original. Whenever I quote Homer, I use Lattimore. (My edition, The Iliad of Homer, which Rand Castile gave me, was a big, impressive volume; it came out when publishers could still afford such books. Besides, it comes with illustrations by Leonard Baskin, and that helps!)

Luckring: Your translation of Oku no Hosumichi (Bashō’s Narrow Road: Spring and Autumn Passage) finally cracked that work open for me. I greatly appreciated the layout of the annotations presented on the facing page of the text. I needed the contextualization to fully appreciate what was going on, and it made the piece come alive for me like never before. And yet, aren’t you saying that Burton Watson’s way of avoiding such kinds of explication appeals to you?

Sato: I think many writings require explications for proper understanding. Burt chose poems to translate that readily make sense to the modern English readers without many annotations and footnotes, limiting them to the minimum. Still, pieces that appear to make sense in straight translation may be properly understood only when the background is provided. Take the following piece by Bashō:

鷹一つ見付けてうれし伊良湖崎

Taka hitotsu mitukete ureshi Irago-zaki

I’m happy to find a single hawk at Irago Cape

Now, I don’t know if Burt ever translated this, and if he did, if he would have cast this in a triplet; but three lines or one line, this hokku should make perfect sense straightforwardly translated, but you may miss what lay behind this simple composition. On the other hand, once you start to annotate, you will find a lot of things to explain. Even that “old pond / frog” hokku requires a sizable amount of explication to tell the reader why it appealed to the people of Bashō’s day. Burt decided not to do any such explanation — most of the time.

Luckring: How do you deal with the importance of sound and prosody in translating poetry, particularly in moving from the vowel-laden, polysyllabic, relatively unstressed meter of Japanese into English?

Sato: The question on what to do with sound reminds me of the time I translated Hagiwara Sakutarō (1886–1942) — more than forty years ago. His first book of poems, Howling at the Moon (Tsuki ni hoeru) — now in Cat Town from the New York Review of Books — has two poems with the title Také (竹), “Bamboo” (aside from Kitahara Hakushū’s comments on what také might mean to his friend Sakutarō in his preface). I do not know exactly how “bamboo” sounds to those who grew up with English, but také, to the Japanese, suggests something straight, sharp (as Sakutarō himself says in two poems: masugunaru, surudoki, surudoku, masshigura[5]). It didn’t take me a long time to decide that the differences in sound between Japanese and English couldn’t be reconciled. Since then, I haven’t generally [taken] into consideration sound and other prosodic differences between Japanese and English.

One exception I had to make was the modern poet Yoshimasu Gōzō (b. 1939). I had to take his use of alliteration into account because his poetry (shi, free verse — not tanka or haiku) heavily depends on alliterative associations. However, in his case, the only thing that’s in common between Gōzō’s originals and my translations is that both use alliterations: the meanings of the words chosen have nothing in common. (For example, suppose Gōzō wrote ka, kamo, kakusu, kanban, etc.; I’d say, “can, cabin, caboose, camera, etc.” instead of translating them, “mosquito, duck, hide, billboard, etc.”) You may want to check it out in Alice Iris Red Horse: Selected Poems of Gozo Yoshimasu, ed. Forrest Gander (New Directions, 2015).

In regard to the differences in syllabic values between the two languages, R. H. Blyth gives funny examples somewhere in one of his many volumes on haiku and senryu to show what could happen when you applied five-seven-five syllables all the time in English translation. I vaguely remember Blyth citing long English words with few syllables to show how ridiculous things result with seventeen syllables in English.

Generally, as you know, you can say more in the same number of syllables in English than in Japanese. Take “frog”: in English it has just one syllable, but in Japanese, kawazu (kaeru) has three. So, when Bashō says kawazu tobikomu, using up all the seven syllables in the middle phrase, you need just two, three, or four syllables to say the same thing in English: “frog jumps,” “a frog jumps,” or “a frog jumps in.”

This explains how, as more and more “literal” translations of Japanese haiku into English were made, American haiku writers realized that Japanese haiku writers don’t say much in their compositions, and so, I gather, they began writing haiku with (far) fewer than seventeen syllables. (I may be wrong about this, of course.)

Conversely, English haiku written in seventeen syllables can say a lot more than the usual Japanese haiku written in the same number of syllables. O. Mabson Southard did not deviate from seventeen syllables divided into three lines, turning out some wonderful haiku that I admire.

Now, even as I disregard syllabic counts in translating Japanese haiku into English, I try to maintain seventeen syllables in translating English haiku into Japanese — for fear that otherwise no Japanese reader would accept my translations as those of haiku! (As you know, in Japan all haiku writers, even Natsuishi, write on the premise that the haiku is based on seventeen syllables.) That in turn means that when I translate Southard’s seventeen, I often have to drop words. For example, here’s one of my favorites:

Across a still lake

through upcurls of morning mist —

the cry of a loon

The best I can do is this:

湖の

朝霧舞うや

アビの声

Mizu’umi no

asagiri mau ya

abi no koe

In this translation, “still” is dropped, “upcurls” is condensed or given in a simpler expression, and “through” is skipped.

Luckring: And yet historically there have been many haiku written outside of the seventeen-syllable form due to the efforts of Hekigodō and Seisensui. Why do you think jiyūritsu (free-form) and the early-twentieth-century experimenters did not have a more long-lasting impact on the genre?

Sato: When I wrote a book in Japanese about English-language haiku, Eigo Haiku 英語俳句, (Simul Shuppankai, 1987), I wrote something like “American haiku writers are innovative,” though I don’t remember if I said, “In contrast, Japanese haiku writers are not.”

I am put off whenever an American reporter mentions “Japanese conformism” (the latest I noticed from the Washington Post: “In Japan, a campaign against high heels targets conformity”). The New York Times regards conformism as the baseline for their reportage on Japan.

That said, I must point out that jiyūritsu itself is still practiced. As a matter of fact, Seisensui’s magazine, Sōun, still continues, though in a different format. And Hekigodō’s magazine, Kaikō, continues. (Interestingly, the Hekigodō school, as it were, survived among the Japanese immigrants in the United States. You can read this in May Sky: There Is Always Tomorrow: An Anthology of Japanese American Concentration Camp Kaiko Haiku [Sun and Moon, 1997]. If this influence continues to this day, I don’t know.)

It’s simply that jiyūritsu hasn’t become the mainstream. Also, it has mostly stayed in a monolinear format, with few people trying anything like multilinear, “concrete” haiku. In addition, I gather that jiyūritsu people stopped writing anything overtly antigovernment, antimilitary, antitraditional, etc. as they did during the Proletariat Literature movement that the thought police suppressed. Today when haiku writers try to be nontraditional in the monolinear format, they tend to be surrealistic, or write “puzzlers,” like Katō Ikuya’s — although I must say many haiku composed in “traditional” ways come across as “puzzlers.”

Not long after the Asia-Pacific War, the scholar Yamamoto Kenkichi (1907–1988) announced essentially that he would not regard as haiku anything not adhering to yūki teikei (the set form of five-seven-five syllables with a kigo). Yamamoto might not have meant it as conformism, but there are two reasons for these standards, at least in Japan, I think. First, with such a short verseform, you don’t have the sense that you have turned out a haiku unless you maintain the set form. Secondly, the prevalent way that haiku compositions are made is in the master-disciple format — if you can write anything as you please and call it a haiku, you don’t really need any teacher.

Luckring: Well, if kigo are mandated as a necessary component of haiku, there is actually much to be studied because they are codified and rely on allusion, and yet that cultural history does not exist outside of Japan. And of course, one’s seasonal “experience” varies greatly by location and culture. By the way, I remember you discussing in your introduction to Santōka: Grass and Tree Cairn (Red Moon Press, 2002) how the Haijin Kyōkai, the largest association of traditional haiku writers, asked publishers not to cite work by nontraditional haijin, such as Taneda Santōka or Ozaki Hōsai, in school textbooks.

Sato: On the other hand, aside from those Scott Metz assembled under The Roadrunner, Chris Gordon, you, and a few others I know, most haiku in America tend to be those that attempt to capture “a moment,” emphasizing nature, or something else, so it seems that the set form is not really important here.[6]

I’d like to mention another thing: the tolerance of haiku for self-explications (jikai). (I gave an example of this with Iijima Haruko [1921–2000] in Japanese Women Poets.) Back in 1978, the Haiku Society of America invited critic Yamamoto Kenkichi to New York, along with the traditionalist haiku poet Mori Sumio (1919–2010).

Yamamoto wrote somewhere that Masaoka Shiki’s haiku might not be interesting on their own, but that many of them would become fascinating if you learned more about his life, the prose pieces he wrote to go with them. I don’t know if he had the New Criticism in mind when he wrote this, but when I was at the English department of Doshisha during the 1960s, it was the only literary theory we were taught. (It would soon be eclipsed by postmodernism, deconstruction, and other approaches.)

The New Criticism argued, as I understood it, that a poem or a prose story should be understood (and analyzed) on its own. It essentially rejected both intentional and affective fallacies. Let’s look at examples of the acceptance of both fallacies, intentional and affective, from Mori Sumio:

磧にて白桃むけば水過ぎゆく

Kawara nite hakutō mukeba mizu sugiyuku[7]

On a riverbed I peel a white peach and the water passes away

What the reader gets from this haiku is anybody’s guess, but Mori explained how and when he wrote it, while traveling in Noto Peninsula and Niigata to its east in 1955. When he reached the upriver of the Hime-kawa, “Princess River,” he found it had the appearance of a tenjō-gawa, a “ceiling river” — a river that has come to flow above the surrounding area as a result of centuries of accumulation of soil along its banks. (They say this kind of river often causes floods.) When he got down to its riverbed, the white stones there emitted a wilderness of white light. There, in their midst, he noticed a stream of fresh water flowing. When he peeled a peach with its fuzzy skin, he was struck by a certain anxiety. Mori adds that someone wrote that this haiku reminded them of James Joyce’s “stream of consciousness,” and this reminded Mori that when he wrote this haiku, he became aware that his youth had come to an end. (He was past age thirty-five.)

If this can be an example of intentional fallacy — not that I know of anybody who has taken Mori’s “self-explication” at face value, but here I refer to the fact that such self-explications are largely accepted — Mori cites another haiku of his (among many others, I’m sure), which may give an example of affective fallacy. He explained the following haiku in 1951 when he was a very poor high school teacher:

家に時計なければ雪はとめどなし

Ie ni tokei nakereba yuki ha tomedonashi

Because there’s no clock in my house the snow unstoppable

About this, the haiku poet and professor of Japanese literature Kawasaki Tenkō (1927–2009) noted what Mori recounts: “there is no clock in the [poet’s] house. And so the snow continues to fall unstoppably down on Sumio’s heart … A clock is presented, then erased, retains an image in the reader’s heart, and by the subtle correspondence between it and the unrealistic clock, the world of the snow deepens more and more, and continues to expand.”

Luckring: It seems that Japanese critical approaches to haiku were in direct opposition to the New Criticism you were studying in school. Speaking of theoretical stances, though you have written about this in multiple places, perhaps you could briefly reiterate here why you have chosen to translate Japanese haiku and tanka as monostich in English?

Sato: To be honest, I haven’t figured out how to explain my practice technically, prosodically. I’ll list a few things that come to mind.

Practically all Japanese haiku and tanka writers print them in one line, though they write them in various lines when writing their compositions for aesthetic presentations, such as for shikishi and tanzaku. You can see examples readily on the internet.

Non-haiku, non-tanka poets and commentators cite them in one line. When someone like Takamura Kōtarō writes haiku or tanka, they stick to the monolinear format in their compositions. That suggests that when the haiku or tanka are written in multiple lines, they may feel they lose “haikuesqueness,” “tankaesqueness,” as it were.

I haven’t seen many prosodic analyses of Japanese five-seven-syllabic patterns written by Japanese critics. Hinatsu Kōnosuke (1890–1971), the old-style professor of English and a Symbolist poet, was one of the few who I noticed. He said that neither the five- nor the seven-syllabic unit, by itself, could function as a line of verse. It was the combination of seven plus five or five plus seven sounds (on) in Japanese verse that “possessed a general suitability in [creating] poetic effect” — up to the end of the Edo Period (1603–1868). He made this observation in his history of [the] poetry of Meiji (1868–1912) and Taishō (1912–1926), Meiji Taishō Shishi, I (Sōgensha, 1948).[8]

Needless to say, “general suitability in creating poetic effect” (shiteki kōka no … ippanteki datōsei) is ambiguous at best. And, in any case, shorter phrases had been used elsewhere in foreign poetry. Also, when Hinatsu was writing his book, which eventually spanned three volumes, great translations were being made. For short verse lines, take his contemporary, scholar Ueda Bin (1874–1916), who had already been translating each line of Chanson d’automne into five syllables:

Les sanglots longs

Des violons

De l’automne

Blessent mon cœur

D’une langueur

Monotone.

秋の日の

ヰ゛オロンの

ためいきの

身にしみて

ひたぶるに

うら悲し。

In the meantime, Ōoka Makoto (1931–2017), a Surrealist poet and a prolific critic, once pointed out that it would be ridiculous to break up Bashō’s hokku into lines, but that doing so might be necessary in foreign translations. More recently (that is, while we have been doing this discussion on haiku), I found that Ōoka, commenting on the three-line haiku of Ōoka Kōji (1937–2003; no relation), said that a few of them might be justified in the trilinear form, but many of them did not show any “necessity” to do so. Kōji started writing haiku in his teens, but after joining Takayanagi Shigenobu’s group in his early twenties, he switched from one-line haiku to three-line haiku — as you might expect (since Takyanagi lineated his haiku).

Now, Ōoka Makoto did not write haiku or tanka, as far as I know, but he became very famous for a small front-page column he wrote for the Asahi Shimbun every day for nearly thirty years — from 1979 to 2007. There he cited a haiku and a tanka — or a line from a poem — and discussed it. It was titled Oriori no uta (Occasional songs), and the column became a fixture, to such an extent that many readers may have come to associate him with the tanka and haiku he quoted.

The feeling that the haiku is a one-line verse probably came from the practice of writing each verse of (haikai no)renga,[9] including the hokku (the first verse), in one line when published on woodblocks during the Edo Period (1603–1868). That doesn’t mean that people in Edo (and before) didn’t think of the syllabic breakdowns of five, seven, five, seven, seven. At a renga session, the scribe would read out each verse when it was submitted, each syllabic unit twice — three times in the case of the hokku. So, the question arose (in retrospect) among modern students of renga: How would a scribe have read out Bashō’s famous irregular hokku?

海くれて鴨の聲ほのかに白し

Umi kurete kamo no koe honokani shiroshi

The sea darkens and the voices of ducks faintly white

As the meaning goes, it breaks down to five-five-seven. But the guess is that the scribe probably read out five-seven-five — that is, umi kurete // kamo no koe hono- // kani shiroshi.

This hokku brings up another technical aspect of haiku (hokku): what may be called “intralinear enjambment,” that is, syntactical units that do not end within the five, seven, or five syllables. In English prosody (and in other languages, probably), enjambment works only when lineation is used, but in Japanese haiku (or poetry), it seems to work only when lines are not used. (In that case, it is unlikely to be called enjambment.) There is a feeling that runover from one line to the next doesn’t work in Japanese as it does in English. The poet Miyoshi Tatsuji (1900–1964) most famously twitted his fellow poet Nishiwaki Junzaburō (1894–1982) on enforcing enjambment on the poems he wrote in Japanese, arguing that it can’t be done. Nishiwaki’s first books of poetry were in English and French.

Here’s another example, a haiku, by Saitō Sanki:

頭悪き日やげんげ田に牛暴れ

Atama waruki hi ya gengeta ni ushi abare

Brain-dead day: in the milkvetch field a bull amuck

The opening phrase, atama waruki, is hypersyllabic, but if you break this up into six plus seven, plus five, atama waruki // hi ya gengeta ni // ushi abare, it will not make much sense, and the disconcerting effect you get from a reading of eight plus five, plus five will be lost. Though I don’t know if this effect can be carried forward by translating the whole thing in one line.

Luckring: Certainly, your one-line translations have inspired writers in the English language to experiment more with monolinear formats that allow the reader to create multiple phrasings and layered meanings, due to the various possibilities of where the cuts (kire) might be heard — what you have called here “interlinear enjambment.”

Scott Metz: Hiro, you wrote in the preface of your recent book On Haiku (New Directions, 2018) that your opinions of haiku upon arriving in the US in the late 1960s were “more negative than positive” and that you felt it was “too short to make it as a poem on its own.” What was it that convinced you that haiku was worth taking more interest in — that it was worthy of study and translation?

Sato: Tricky question! Before I came to this country (that means when I was at Doshisha University in Kyoto), I had studied haiku as an English major. The main question I had then was: How could such short pieces make it as poems? So, I looked for books explaining why and how, in Japanese. One book that impressed me was Yamamoto Kenkichi’s Haiku no Sekai, and it essentially argued that haiku grew out of a “literature of za,” a gathering, za no bungaku, 座の文学, rather than a solitary inspiration. You may argue that this still holds largely true in Japan: regardless of renga, haiku tend to be composed in groups of people. Earl Miner said more or less the same thing, in a different way and from the viewpoint of a scholar of classical English poetry, in his entry on haiku in the first edition of the Princeton Encyclopedia of Poetry and Poetics. (When the editors decided to do a revised edition, he graciously deferred the writing of a new entry to me.)

After I was unexpectedly asked to talk at the Haiku Society of America, one question after another came up because I realized that I hadn’t known much of anything. So, as I learned more, I had more occasions to talk and write about haiku, and I did and have.

Luckring: In addition to group composition itself, it seems to me that part of the “gathering” you mention is demonstrated by haiku’s extensive use of allusion via kigo and the common practice of direct reference to poems by predecessors. As we’ve discussed though, some of the poets you’ve translated from the modern period, like Taneda Santōka and Ozaki Hōsai, abandoned the governing rules for composing hokku, perhaps emphasizing the impact of a haiku’s brevity and fragmentary nature all the more. What drew you to these poets?

Sato: I think I was drawn to Hōsai because he struck me as different: free of the constraints of yūki teikei; his haiku had a kind of immediacy that I didn’t find in the haiku of other writers, so I translated a lot of them. I described what happened as a result in this article.

Metz: And you dedicated Right under the big sky, I don’t wear a hat (Stonebridge Press, 1993) to John Ashbery, who published all 150 of your Hōsai translations when he was poetry editor of the Partisan Review. Do you remember the reactions to Ashbery’s one-line haiku from A Wave when they first appeared?

Sato: I distinctly remember Cor van den Heuvel, who anthologized late-twentieth-century English-language haiku, muttering, upon looking at Ashbery’s haiku, “These are not haiku!” I should remember the exact phrase because that dismissal comes from my memory of our earlier association and friendship. In the days when the Japan Society, New York, still accommodated the Haiku Society of America and allowed it to have its gatherings in its building near the United Nations, Cor would come to the meetings straight from the Newsweek office, where he worked at the time, as stylishly dressed as he always was, and when a member read aloud a piece he didn’t approve of, he would curtly say so with, “That’s not a haiku” (or was it “That’s no haiku”?).

My Japanese translation of A Wave came with a number of reviews from Japanese poets, but, as I said in my article on Ashbery, most people were deferentially puzzled at best, I think, because of Ashbery’s fame.

Luckring: In a 2004 interview with Robert Wilson, you stated, “I’ve always been interested in haiku written by people who are known in fields other than haiku: Dag Hammarskjold, Borges, Richard Wright, Allen Ginsberg.” Please say more about this, especially since poets so commonly specialize in Japan.

Sato: I don’t exactly remember what I meant. Perhaps did I mean people who, outside their professions, did not write haiku to be known for their haiku?

Practically all haiku writers (or haijin) in Japan have proper professions to make a living. Haiku alone doesn’t make you enough income, as you can imagine. For example, Saitō Sanki (1900–1962), though counted among the top dozen haiku-writing “wanderers” according to another haiku writer, Ishikawa Keirō (1909–1975), worked as a dentist much of his life.

Metz: Who do you feel has done something of note? Something unique, unexpected, or new? Any favorites? Why?

Sato: I had always been interested in Dag Hammarskjöld. He was one of the heroes when I was beginning to learn about the world from the 1950s to the 1960s. At the time, the United Nations, revolutionaries, and such had a special fascination for me. Castro, Nasser, Lumumba … so, years later, when I learned that the second UN secretary-general had written haiku, I bought Dag Hammarskjöld: Markings, translated by W. H. Auden (Alfred A. Knopf, 1964). I thought his haiku there seemed to open a new world for haiku. (Later, the Swedish diplomat Kaj Falkman, dissatisfied with Auden’s selection and translation, did his own. But that’s another story.)

One thing that attracted my attention was not just Hammarskjöld’s haiku, starting with

Red evenings in March. News of death.

Begin anew —

What has ended?

but also, the footnote: “In a haiku, the number of syllables in any one line is optional, but the sum total of the three lines most always be seventeen.”

Now, I wondered whether this definition was Auden’s because Auden follows this with his remark: “In my English versions, the number of syllables in any given line may not be the same as the Swedish, but the total for the three is the same.” Later, I gathered it may well have been Hammarskjöld’s own. He may have learned that from a Japanese diplomat at the UN, for around 1920 there was a Japanese haiku theoretician (as it were) who defined the haiku as such — not that the haiku is made up of five-seven-five but that it consists of a total of seventeen, in one line.

About the time Robert Wilson interviewed me, I think I was writing about some of the non-haiku haiku writers for the Japanese-language bimonthly published here, OCS News (OCS stood for Overseas Currier Service), which would soon shut down in the face of the onslaught of the internet. I remember some by Borges via Chris Gordon’s translation.

There was also Allen Ginsberg because my friend Michael O’Brien told me about Ginsberg’s one-line, seventeen-syllable haiku in Death & Fame (Generic, 1999). Michael, who died in November 2016, himself had written haiku in one-line, seventeen-syllable haiku, though he placed two spaces in most of his one-line haiku.

In my articles of OCS News, I also touched on Etheridge Knight because I happened to receive an anthology of 101 American poets in Japanese translation. At the time, I read his haiku only in Japanese translation, but now you can see some of the originals on the Internet.

Eastern guard tower

glints in sunset; convicts rest

like lizards on rocks.

Morning sun slants cell.

Drunks stagger like cripple flies

On jailhouse floor.

And Richard Wright, in Haiku: This Other World (Arcade Publishing, 1998).

As you can imagine, these writers and poets, writing seventeen-syllable haiku, be it in three lines or in one line, bring in sensibilities and outlooks that you don’t seem to get from the haiku of other writers who set out to write “haiku” in English, in an attempt to engender “haikuesqueness,” if I may put it that way. Or, so I might have thought a dozen years ago, partly because seventeen syllables can say a lot more in English than the same number of syllables can in Japanese. Or was it because of something else?

As you say, “poets so commonly specialize in Japan.” There are a few exceptions, however; among them, Takahashi Mutsuo stands out because he won important prizes in each of the three genres: tanka, haiku, and shi, poetry in multiple lines. What makes his case even more interesting is that he makes his haiku very traditional — here meaning the reliance on kigo, or personal, even esoteric, knowledge.

Here are two haiku by Takahashi:

冬の海吐き出す顎のごときもの

Fuyu no umi hakidasu ago no gotoki mono

Winter sea: something like a jaw vomited out

(or)

Winter sea has vomited out something like a jaw

市振や雪にとりつく波がしら

Ichiburi ya yuki ni torituku namigashjira

Ichiburi: wave crests grab at the snow

Perhaps these pieces do not require special knowledge. Maybe these pieces are typical haiku. Anyway, saying these things brings in some questions that I cannot really answer, among them: What makes a haiku a haiku?

Metz: What then would you like Westerners to know most about haiku poetics?

Sato: A few days ago, I received from Japan the book I had ordered, Gendai Haiku Shūsei ([Collection of modern haiku] Rippū Shobō, originally published in 1996). It assembles sixty-one haiku writers, each represented by 150–200 pieces — a total of more than eleven thousand pieces — each haiku writer providing a brief essay on haiku. According to its editor, Sōda Yasumasa (b. 1930), the purpose of this anthology was to give a bird’s-eye view of Japan’s haiku world after the two prominent traditionalists Iida Ryūta (1920–2007) and Mori Sumio (1919–2010), focusing on the “pure-postwar” haiku writers. In this world, the editor points out, there are almost one thousand haiku magazines published by haiku kessha — “organizations,” “societies” — and dōjinshi — “members-only magazines,” in addition to haiku programs on TV and in major newspapers, not to mention “culture haiku classes” held by various organizations as part of “adult education.”

As a result, Sōda observes, some of the haiku writers seek “cosmology,” some seek to “refine haiku traditions,” some try to fathom “the unconscious,” some “consciously” try to be playful as in the haikai world of the past, some try to write haiku according to set subjects (or “themes”), some try to take advantage of the fact that the haiku can say only fragmentary things and express things that can’t be expressed, etc. Sōda adds that the ways women haiku writers have liberated themselves from the spell of Nakamura Teijo (1900–1988), Hashimoto Takako (1899–1963), and Mitsuhashi Takajo (1899–1972) is particularly notable. So, you can see, it will be well-nigh impossible to define haiku or what makes a piece “haikuesque,” except perhaps that it is something written in a total of seventeen syllables, more or less.

Now, of the sixty-one haiku writers selected in this anthology, only three go out of the seventeen-syllable, one-line haiku: Origasa Bishū (1934–1990), Hayashi Kei (b. 1953), and Sumitaku Kenshin (1961–1987). Of the three, Sumitaku is someone I translated and wrote about (now thirty-three years ago!), so let us look at the other two.

Both Origasa and Hayashi studied with Takayanagi Shigenobu and, like him, wrote both five-seven-five-syllable, monolinear as well as multiple-line haiku. There are some differences between their one-liners: Origasa sometimes uses symbols, such as intralinear blanks (spaces) and dots (as Takayanagi did), while Hayashi uses headnotes as part of his one-liners. Here is an example from Origasa’s four-liners:

akeyami wa 暁闇(あけやみ)は

shi ni daki 死に抱き

yūyami 夕闇

koroshidaki 殺し抱き

Daybreak dark

dies and hugs

evening dark

kills and hugs

In this piece, 暁闇, without the reading Origasa provides, will be read gyōan or (in tanka) akatokiyami or akatsukiyami, though it means the same thing: the first quarter of the moon, when the moon does not appear in the sky before the daybreak and so it’s dark. This piece consists of a total of seventeen syllables.

Here is a multiliner of Hayashi Kei:

Bara no anbu no 薔薇(ばら)の暗部(あんぶ)の

chichi chō 父(ちち)てふ

haha chō 母(はは)てふ

kaikyaku yo 開脚(かいきゃく)よ

In the dark part of the rose

father so-called

mother so-called

legs open

Hayashi gives readings to all kanji, though the readings here are all standard. This piece consists of seven / four / four / five syllables.

Kamakura Sayumi (b. 1953), who is married to Natsuishi Ban’ya (b. 1955), has said about the kind of haiku she writes, or her definition of the haiku:

The haiku can become a vessel into which you can pour all kinds of human thoughts. As long as you try to change the contents of expressions, it can show you all sorts of different faces. Excepting the basic of five-seven-five, seventeen syllables in all, in Japanese, there is nothing set for the expression format called haiku.

Again, this may well be tautological, in that everyone seems already to write whatever they like. Here are the last two that end Kamakura’s selection:

夫と妻の隙間しゃぼん玉あがれ

Otto to tsuma no sukima shobondama agare

The space between husband and wife: soap bubble, rise[10]

どこまでも鎖(さ)骨は鳥を追うかたち

Doko made mo sakotsu wa tori o ou katachi

However it goes the collarbone shaped like chasing a bird

So, most Japanese haiku writers stick to the five-seven-five-syllable form, a total of seventeen syllables format, but I do not think there’s anything like “haiku poetics” for Westerners. The days we could say such things are all gone, I think.

Luckring: What qualities might exclude a short poem from being called a haiku, particularly if it is not written in Japanese?

Sato: My response is similar. As Eliot Weinberger said about “poetry” in American Poetry Since 1950 (Marsilio, 1993), it is “that which its own author considers to be poetry.” Likewise, a haiku will depend on what its author considers it to be.

Here let me bring up two Japanese poets (not haiku or tanka poets) who are brought up whenever one-line poems (ichigyō-shi) are mentioned: Anzai Fuyue (1898–1965) and Kitagawa Fuyuhiko (1900–1990). Anzai is always associated with his own one-liner with the title “Spring”:

てふてふが一匹韃靼海峡を渡って行った。

Tefutefu ga ippiki Dattan Kaikyō wo watatte itta.

A butterfly alone flew away across the Tartar Strait.

Kitagawa is remembered for this piece, which comes with the title “Horse.”

軍港を内蔵してゐる。

Gunkō wo naizō shiteiru.

Intestinizes a naval base.[11]

Anzai’s “butterfly” piece will at once make you think of a (traditional) haiku. Indeed, though it appeared in his first book of poems, Gunkan Mari (Warship Mari), in 1929, printed on a single page, later, after Japan’s surrender in 1945, he recast the monostich into a five-seven-five-syllable piece, also printed in one line:

韃靼のわだつみ渡る蝶かな

Dattan no Wadatsumi wataru kochō kaka

Crossing Tartar’s Poseidon: a butterfly[12]

Anzai and Kitagawa writing one-line poems in the 1920s made me think of the influence of French poetry on Japanese poetry, such as Dadaism and Symbolism. So, I took out from the bookshelf my friend Bill Zavatsky’s assemblage of “one-line poems,” published in 1974, a special issue of Roy Rogers. Sure enough, it has a sizable section devoted to French one-liners (in English translation) that begins with the French scholar LeRoy Breunig’s essay, “Apollinaire and the Monostich,” although, interestingly, Apollinaire seems to have written just one, in Alcools (1913):

Et l’unique cordeau de trompettes marines.

Zavatsky’s collection begins with Sappho’s fragments, such as “you burn me.” Among the more recent American poets he quotes, many of whom are (were) his friends, I think, there is a one-liner called “HAIKU,” by Frank Kuenstler:

Fish swim. They die. They rise to the surface. It is their way of falling.

Now, if you count the syllables, you’ll see that there are seventeen. In those days in the early 1970s, Kuenstler was a friend of mine, and I translated some of his poems for the Japanese poetry monthly Gendaishi Techō. Michael O’Brien, who was devoted to him, didn’t come to seventeen-syllable, one-line haiku until much later, so among the poets I knew, Kuenstler may have been the first to write seventeen-syllable, one-line haiku.

Luckring: And so we are back to questions of lineation, how seventeen syllables say a heck of a lot more in English (and other languages) than in Japanese, and the fact that the set form of five-seven-five reflects haiku’s genealogical evolution from tanka and linked-verse forms.

On the related topic of kigo — when asked about what haiku might become outside of Japan, Stanford Professor Emeritus Makoto Ueda, who, like you, has translated twentieth-century, modern Japanese haiku into English, said that “my hope is that an English haiku has some kind of ‘flavor of nature’ somewhere, because nature is a basic part of haiku.” Any comments?

Sato: Ueda Sensei, whom I met once, in a conference back in 1982, was kind to me and sent me his books even after I wrote some critical things about his translations.

I am not surprised by his comment that haiku in English should retain some “flavor of nature” because there may be an increasing number of English writers who appear to see the inspiration of the “haiku” mainly in its form — be it a tercet or monolinear — or its brevity or ephemerality. Ueda Sensei is a scholar steeped in classical haiku. That reminds me: the late Earl Miner, likewise steeped in classical Japanese poetry, had a low opinion of haiku written in English, dismissing them as Hallmark card greetings.

Metz: I want to mention Japanese Women Poets (Routledge, 2007); it is a monumental work. What inspired you to tackle a five-hundred-page-plus book of translations focusing exclusively on female poets?

Sato: I thought of the idea of an anthology of Japanese women poets because there was a strong interest in women in the 1980s, even after From the Country of Eight Islands (University of Washington Press, 1981), the one I did with Burton Watson, came out. (That interest, of course, has remained strong since, but I have the general sense that the focus of the interest has shifted.) When it comes to women in Japan, there was, at the time, an assumption in this country that women were unjustly treated by society — some of the sense that Tomioka Taeko, et al. evidently shared.

There is also the fact that four of my siblings are sisters, women.

Anyway, there already was an anthology of Japanese women poets by Atsumi Ikuko and Kenneth Rexroth, as you know, but I thought it was an utterly hasty patchwork job.

Luckring: I know you have translated monographs of Shikishi, Ema Saikō, and Tomioka Taeko; are there other poets in the anthology you would like to translate more extensively in the future?

Sato: I never thought of it, though Mayuzumi Madoka asked me to do a book of her haiku. One result was her anthology of haiku on the consequences of the 2011 earthquake and tsunami disaster, which I, with my wife Nancy, turned into So Happy to See Cherry Blossoms: Haiku from the Year of the Earthquake and Tsunami (Red Moon Press, 2014). It is a selection, though, not a complete translation.

If there is any woman poet I might want to do in the future, that person is Yosano Akiko. She is known almost exclusively for her romantic tanka that initially made her famous and her one antiwar poem (shi) written during the Russo-Japanese War, but she wrote many shi, and they are far more interesting to me!

Luckring: Do you think your positioning outside of academia has affected the type of audiences your work reaches?

Sato: As I recall, I didn’t think of anything like that simply because I did not know about academia. I did what I wanted to do. The state of these things in publishing when I started translating was such that the august Yomiuri Shimbun gave a whole page (minus ad space) to praise me when Ten Japanese Poets (Granite Publications, 1973) and the Chicago Review devoted a special issue to my translations (minus a manga story — which the New York Times pompously today calls “graphic novels”). Such things change quickly. Less than ten years later, when I did my big work with Burton Watson, From the Country of Eight Islands, none of the main newspapers — Yomiuri, Asahi, Mainichi — touched it, so I had to ask a Mainichi reporter I knew at the time to do something, and he gave me a small space to describe it in his daily.

Luckring: Years later you published Legends of the Samurai in 1995 (The Overlook Press), and your most recent projects return to this theme — Death and the Samurai, now in progress, and Forty-Seven Samurai: A Tale of Vengeance and Death in Haiku and Letters out from Stone Bridge Press in 2019. What interests you in these warrior tales and their connection to poetry?

Sato: In the 1950s and 1960s, we Japanese boys grew up with Westerns from Hollywood and samurai movies, although I probably did not see Kurosawa Akira’s Yōjinbō and Kobayashi Masaki’s Seppuku (English: Harakiri) until after I settled down in New York City. Then, in 1970, Mishima committed seppuku in such an open, spectacular way!

Then, in the 1980s — as you recall, the talk during the decade was about how Japan was taking over the world economy — there was news that Harvard Business School was using Miyamoto Musashi’s Gorin no sho as a textbook, thinking this to be a key to understanding Japan’s business success. I took a look at the translation and thought I could do better (or something like that). Later I learned several translators had a similar thought, so suddenly there were several translations of the same tract on how to fight with sword(s). In my case, the result was The Sword and the Mind (Overlook, 1985), a treatise on swordsmanship not by Miyamoto Musashi but by his contemporary swordsman Yagyū Munenori. Later I was embarrassed to realize that I didn’t even know the importance of kata (fixed forms for training) in swordsmanship when I did the translation!

Poetry and the samurai were linked together from the start — beginning with the mythical Yamato Takeru, as the Kojiki and Nihon Shoki tell it …

Luckring: Perhaps we can close our conversation with a poem you’ve translated for your latest book?

Sato: Thank you for asking. One reason I wrote Forty-Seven Samurai: A Tale of Vengeance was my discovery, via the haiku scholar Fukumoto Ichirō’s book Haiku Chūshingura, that several of the men wrote haiku (hokku). Among them, Ōtaka Gengo is regarded as having left the best jisei, afarewell-to-the-world haiku. Here it is:

山を抜く力も折れて松の雪

Yama o nuku chikara mo orete matsu no yuki

Scaling the mountain my strength broken: snow on the pine[13]

Luckring: What a way to end. Thank you, Hiro, for all your time and thoughtfulness.

1. Senryū is a five-seven-five syllable form derived from a verse-linking game, maekuzuke, named after the comic verses written by Karai Senryū.

2. Hokku is the opening verse of renga, collaboratively composed linked-verse. Hokku were traditionally written in five-seven-five syllables with a kigo (see note 4). They were often collected and published together in linked-verse anthologies, while haiku developed from Shiki’s efforts to modernize the form as a standalone poem at the end of the nineteenth century.

3. Still, Kōtarō, son of a famous Buddhist sculptor, studied Western sculpture there, and captivated by Rodin as he was, went to Paris, via New York and London, to study with him. Though he failed to meet him, he was so enchanted by Paris, France, that he even wrote something like this:

Gratitude

Thank you, France.

Understanding brightens mankind.

Even in the way a woman

poured me café au lait one morning,

ah, you revealed it.

Although he was annoyed by all the talk about Japonism and wrote “Comic Verse” to express it, later supported Japan’s militarism in the 1930s and 1940s, and belatedly discovered “art” (loaded word!) in his father’s sculptures, his admiration for Western art never flagged. I’m sure he’d be tickled to learn that the American composer Stephen Hartke would put to music his poem exalting the Cathedral of Notre Dame. See A Brief History of Imbecility: Poetry and Prose of Takamura Kōtarō, trans. Hiroaki Sato (Honolulu, HI: University of Hawaii Press, 1992), 47. This is an expanded edition of Chieko and Other Poems.

4. To follow what Haikai Dai-jiten says, a kigo is defined as a word or a phrase that is ideally linked to a particular season. For example, kuina, 水鶏, “ruddy crake,” in Japan, represents “lunar” summer in poetry even though it is observed well into “lunar” autumn. Kigo are sometimes used to allude to other poems using the same kigo, some written centuries earlier, though the majority of kigo were created in the twentieth century. Saijikis, which list kigo according to season, provide haiku examples for each entry. Modern versions are organized into the four seasons and the New Year, with some containing seasonless (無季, muki) topics.

5. You can read the original poems here.

6. Nevertheless, there has been a group of practitioners dedicated to yūki teikei in Northern California since 1975.

7. Naka Tarō (1922–2014) praised the subtle use and arrangement of vowels in this haiku: i, u, u, i, u, and u, as well the repeated use of the consonant m. Naka was a poet known particularly for his clever use of sounds in his poetry.

8. See also Hiroaki Sato, “Lineation of Tanka in English Translation,” Monumenta Nipponica 42, no. 3 (Autumn 1987): 347–56.

9. A form of renga (collaborative linked-verse) that became increasingly popular beginning in the sixteenth century. It is more playful and humorous than ushin renga in its use of vernacular and defiance of courtly poetic tradition. Bashō is credited with evolving the genre to greater aesthetic sensitivity in the late seventeenth century.

10. My haiku poet friend Ōtaka Shō gave me this reading above and the syntactical breakdown: ten / eight. Actually, Kamakura frequently uses hypersyllabic haiku, despite her comment on five-seven-five, seventeen syllables.

11. Intestinize is a word I made up because Kitagawa uses naizō, “intestine,” as a verb by adding suru. In his case, I assume the “title” is part of the one-liner.

12. Wadatsumi is the counterpart of Poseidon in Japanese mythology. It also means the sea, the ocean. Here, dattan may come out as three or even two and a half syllables in English, but it comes out as four syllables in Japanese, with n ん counted as one syllable. Likewise, kochō may come across as two syllables in English, but in Japanese it’s counted as three syllables. Sokuonbin, or “consonant flight,” was a subject of discussion among the early members of the Haiku Society of America.

13. This jisei appears to have a variant: katana, “sword,” instead of chikara, “strength,” though Fukumoto sticks to chikara.