On Larry Eigner, ‘On My Eyes’

I really wish that I could do what Judith Goldman was able to do. [1] I’ve always wanted to give a presentation in which I stop talking and moving my lips but my voice continues on. But whenever I do that, I just get silence … I got very nervous when Chris Funkhouser actually does the full fifteen seconds of silence in Mac Low’s poems. I would have said three or four seconds made the point. It was excruciating, fifteen seconds. We each have only five minutes and you use up that much time?!

The Mac Low really reminded me, especially in that silence, of what Danny started out with, with Cage, and I thought again of Larry Eigner, who I am going to talk about tonight. Also, with Rachel’s talk: Larry Eigner was the least cosmopolitan of people in the 1950s and Frank O’Hara the most. And yet, “Second Avenue” is a kind of point of intersection phenomenologically, where you can almost see that there’s a connection. Also, the book I am going to talk about, has a preface by Denise Levertov …

As I’m listening to this, I keep thinking somebody else is going to listen to this not in terms of what we’re saying about the poets we are talking about, but [in terms of] the nature of the event and what we’re enacting in the affectional preferences that we are showing, and the generational unconscious and, to some degree, conscious. I think, especially for those of us born immediately after the Second World War, the poets that we are talking about are our parents’ generation, and whether positive or negative you have that agonism played out. So, it’s a little bit different when I think of Barbara Guest and when I hear Erica speak about her. And that generational difference is one of the things that I kept thinking about in both respect to me and Larry Eigner: why I chose Eigner, why I have such a strong affectional connection to him, and some of the other [poets of his generation]. The other is the ongoing frame that Filreis provides especially with Counter-Revolution of the Word. I always say, and so those of you who have spent more than a couple of hours with me will know, that I’m stuck in the ’50s, so this event is the perfect thing: we’re all together, we’re all going to be stuck in the ’50s now because while the books come out in 1960, we’re really talking about work done in ’50s, that comes out of the ’50s and the deep Cold War. And very different perspectives on it. I think beginning with Stanley Kunitz was wild on Al’s part, and nobody really has picked up on that, but for me, of course, I think of maybe Larry Eigner and Stanley Kunitz are two possible uncles, one more like my father, Stanley Kunitz, in terms of his views, so I kept thinking about that, too. And then there's Stanley Kunitz in Worcester, early on dealing with Sacco and Vanzetti. There’s Charles Olson [born] one hundred years ago in Worcester. And Robert Creeley in Acton, Massachusetts, and Larry Eigner in Swampscott. So, you have a kind of New England matrix.

So, this book, I have only about a minute left actually, I’m at four minutes, and I think I just want to conclude my remarks now.

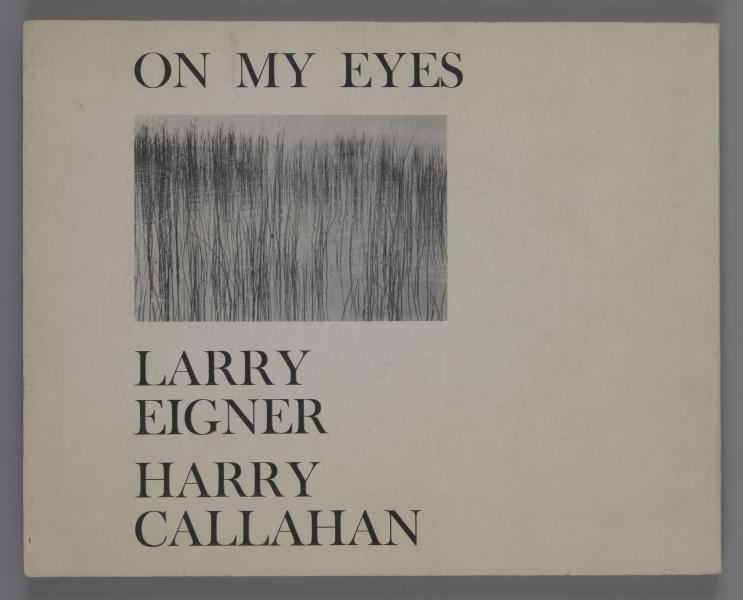

This book was published in 1960 [by Jargon Press, Highlands, NC, in an edition of 500]. It’s Eigner’s first large collection and I think that it’s notable for the way it really brings him into the world. And, again, to [add to] the tributes to people, Jonathan Williams having the foresight to publish a substantial collection of Larry Eigner in 1960 is extraordinary. And with beautiful Harry Callahan photos, so the book itself is beautiful. There was just one earlier book, very small, [from] 1953, that Creeley published, From the Sustaining Air, which echoes again something that Al said in the beginning about what kind of air, the sustaining air. So, Eigner, just to remind you … [was] born in 1927. If you compare this book, which is a great opportunity we now have, to the first volume of the [Robert Grenier / Curtis Faville] collected [four volumes from Stanford University Press, 2010], you really get a very different sense of what was going on. The work [covered in On My Eyes] goes back to ’53, so it’s really a lot of earlier stuff than one might imagine for a book [published in] ’60. When you read the whole set of what Larry was doing, it’s much different [than the sense you get from the book]. Not that these [poems in the book] are necessarily literary in any conventional sense, but in some ways there are more literary picks of the poems than  when you read the whole [body of work from the period]. [In the Collected] you see work starting out from when Larry was in junior high school. You really get a sense of the impact in his own mind, first of all, very importantly, of the typewriter he got for a Bar Mitzvah present when he was thirteen, and the fact that because he suffered from palsy when he was born, because of the way in which he was delivered, he could only really type with the one finger. Once he learned to type for himself — his mother had earlier typed for him — he could express himself, and spent all of his time working on that typewriter page. I mean, it’s one of the really monumental achievements of American art in my view, what Eigner achieved that way, and actually in an entirely [familial but otherwise largely] unsocial space of the ’50s. So, you see work that seems so cosmopolitan, so cosmically vivid, done by somebody who really hadn't had that much contact with anybody else outside his family. In ’49, he hears Cid Corman on the radio. He writes him a letter saying, “Your reading of Yeats is not emphatic enough. What’s wrong with it?” And after that, he meets Creeley, very importantly, and others, and he starts to move into the opening of the field that Ron refers to, and writes these extraordinary poems. He ends the wonderful From the Sustaining Air, which could be my motto as a writer of verse, “I am finally an incompetent after all.” 1953. “I am finally an incompetent after all.” A stunning comment at the end of a very beautiful poem.

when you read the whole [body of work from the period]. [In the Collected] you see work starting out from when Larry was in junior high school. You really get a sense of the impact in his own mind, first of all, very importantly, of the typewriter he got for a Bar Mitzvah present when he was thirteen, and the fact that because he suffered from palsy when he was born, because of the way in which he was delivered, he could only really type with the one finger. Once he learned to type for himself — his mother had earlier typed for him — he could express himself, and spent all of his time working on that typewriter page. I mean, it’s one of the really monumental achievements of American art in my view, what Eigner achieved that way, and actually in an entirely [familial but otherwise largely] unsocial space of the ’50s. So, you see work that seems so cosmopolitan, so cosmically vivid, done by somebody who really hadn't had that much contact with anybody else outside his family. In ’49, he hears Cid Corman on the radio. He writes him a letter saying, “Your reading of Yeats is not emphatic enough. What’s wrong with it?” And after that, he meets Creeley, very importantly, and others, and he starts to move into the opening of the field that Ron refers to, and writes these extraordinary poems. He ends the wonderful From the Sustaining Air, which could be my motto as a writer of verse, “I am finally an incompetent after all.” 1953. “I am finally an incompetent after all.” A stunning comment at the end of a very beautiful poem.

However, I’m also really interested in this poem, which I’m going to read and then quote one of the lines, “So what if mankind dies,” he writes in On My Eyes, which is the name of the book I’m talking about: on my eyes, what I’m seeing

so what if mankind dies?

the birds

the croak and whistle

has no future

so what?

so what?

the future arrives

the end of stick

in my crotch

toward the speed of light

(Collected I:160, 1955 # k ’)

So, I mean it’s an extraordinary poem about the nature of the phallus, a hard-on, being just about as far as where the future is gonna go for Eigner. Again, a 1955 comment on progress from Swampscott. And I want to end with a quote from a poem of his, the name of this piece is called

Eigner’s Fierce Calculus

… but please, in the transcription, keep the title right there because this is a talking essay.

“The Dead dog” poem that he writes in 1957 (Collected. I:266, December 57 # 2 b), I think he answers for, in a way, generationally, for me what I like so much about these poets of the 1950s, and he answers Corman, too, at the end of “The Dead dog,” he says, “but someday the grandmothers may grow wise / and speak the calculus” — and “calculus” is a term for him which really pervades, and it’s an alternative to “another time in fragments” and Benjamin’s constellation, it’s the idea that these individual, discrete, burning particulars together make a calculus that’s a three or four-dimensional calculus — and ends “making a fierce language.”

Thanks.

[1] Charles Bernstein presented this improvised talk following the glitchy video projection of Judith Goldman’s presentation on The Bean Eaters by Gwendolyn Brooks at the Poetry in 1960 Symposium, December 6, 2010.

Edited by Al Filreis