To undo the human

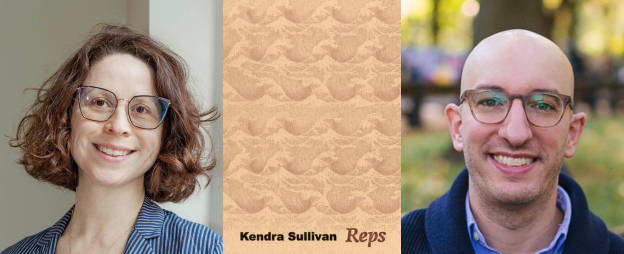

Kendra Sullivan in conversation with Louis Bury

Kendra Sullivan operates in the vital tradition of poets who undertake DIY cultural work. She is the Director of the CUNY Graduate Center’s Center for Humanities, where she is responsible for initiatives such as Lost & Found: The CUNY Poetics Archive Initiative and NYC Climate Justice Hub. She co-founded the Sunview Luncheonette, a cooperative arts venue in Brooklyn, and is a member of Mare Liberum, an eco-arts collective. She’s generous and warm in these capacities, as well as in her capacities as partner (to the artist Dylan Gauthier), parent (to their son Demitri), and friend and acquaintance (to many throughout NYC literary and arts communities). We spoke together on the occasion of her recent Ugly Duckling Presse book, Reps, which uses undisclosed constraints as carrying cases — safe deposit boxes — for the stories humans tell each other to make sense of their many capacities.

— Louis Bury

***

Louis Bury: Where does the title of your book, Reps, come from?

Kendra Sullivan: I was thinking about representation, repetition, and reproductive labor. For Lost & Found: The CUNY Poetics Archive Initiative, we published one of Kathy Acker’s early notebooks, which included a series of exercises for Leroi Jones. I was taken with the idea of regularity or steadiness as an end goal. An undercurrent of Reps is repair. I was thinking about how to repair the individual and collective body, the personal and intrapersonal self.

Bury: Bernadette Mayer’s well-known list of writing experiments feels similar but even more so her book Midwinter’s Day, especially in the context of parenting and ordinariness.

Sullivan: Absolutely! I love Midwinter’s Day. My son Demitri once showed up in a poem by one of my favorite NYC poets, Anna Gurton-Wachter. We had all attended a marathon reading on the solstice. He was an infant with reflux and had projectile vomited, so when I read from a section that ended, “babies are insane,” in a dress mottled with milk, it felt right. Anna asked consent to include us in her poem, and consent has been a method for me ever since. It transforms the writing process from one of private introspection to public intellection. It’s a powerful act of connection and surrender.

Bury: The first section of Reps, “Exercises Against Empathy,” contains paired poems that each share the same title but have different parenthetical subtitles, such as “Hut (Shelter)” and “Hut (Attention).” Can you talk about the wordplay prevalent throughout the book?

Sullivan: Wordplay is my path through language. I rely on it to disengage from correct syntax and stringent grammatical rules. Wordplay suggests to me divergent routes driven by accident and mishap. It’s setting out with an intention but not an expectation, leaving the house with no place to go. It’s a way of courting coincidence and disruption.

Bury: A good example of that occurs in the first poem, “ALEX,” of the book’s second section, “A Typology of Possible Biographies,” where you write: “A story about parents’ preference for the present/ miscast as reverence for their children’s futures// futures/ past parents/ forget to protect/ present parents from.” The second stanza is propelled forward by sound as much as sense. Can you talk about this section of the book, which if I understand correctly is organized around experiments in collective memory?

Sullivan: I’d be happy to but first I’d be curious to hear you describe what’s happening in that section without your having any background information. You’re someone who has worked with constraints so I’m curious how the constraints I used appear to you.

Bury: Let’s do it! Each poem in “A Typology of Possible Biographies” has a name as its title, such as “ALEX” or “ANA.” The poems’ contents are essentially lists of generalized stories about that person. The stories presumably correspond to the title characters but they contain few concrete details, which gives them a feeling of universality, that each story could be anybody’s. I took that universal quality as the effect you were going for with writing about collective memory.

Sullivan: Thank you for going there with me. You’re close. Here was my process. As acquaintances told me three-minute versions of their lives, I reverse-engineered a stream of writing prompts that began with the command, “Write a story about…” Deep listening and oral history are regenerative practices, in that the more you share the more there is to share. I’m interested in what might a biography of scale look like, chronicling only points of interaction on a network. The significance of individual bodies, choices, and stories pale in comparison to larger-scale patterns of resource use and waste production. At the same time, the humanities help us question the dehumanizing logic of statistics and acceptable risk that undergird war strategy and toxicity management. I believe we need to undo the human without hurting anyone.

Bury: It’s as though you’re composting your acquaintances’ stories. The thing I hadn’t realized while reading is that each poem is based on a true story; I imagined the stories were hypothetical or potential.

Sullivan: Right, the details may be hidden but the fulcrum is a real human life. I imagined the stories like stones dropping through a lake. The weight of the human story is at the center, its effects ripple outwards, and the lake is still just a lake.

Bury: In literary history, many individual writers, as well as collectives such as OuLiPo, use constraints in ways that keep their subject matter’s emotional content at arm’s length. It’s a stereotypically masculine attitude toward one’s own feelings.

Sullivan: One of my favorite books is Lucy Ives’ novel, The Hermit, which is about a person who lives isolated in a hut and contemplates the shape of a perfect novel. I’m enamored with the idea that literary structures can keep stories safe, like a turtle shell or Robinson Crusoe’s castle. There’s a concept in geometry called topology, which refers to a process by which a shape undergoes continuous transformation without losing its “itness.” I’m interested in how a similar idea might apply to literature.

Bury: What you say about topology reminds me of lines in your book about maps and mimesis. For example, you write: “I’m hard-pressed to think of any mode of representation that doesn’t flatten reality to some degree.” And also: “A version of Earth that ignores its own suffering is called a map.”

Sullivan: The human relationship to the Earth might be described as topological: how far can we stretch, bend, and twist the planet without losing its livability? In his 2014 book, The Great Derangement, Amitav Ghosh makes the point that narrative itself has been a co-conspirator of colonialism and capitalism.

Bury: Climate fiction, with its apocalyptic narratives, has a greater purchase on the public imagination than ecopoetry.

Sullivan: This goes back to your initial question about my book’s title, the way reps can be a way to train for a test or trial. Climate change requires us to prepare for transformations: cataclysms surely, but maybe also, in the full arc of time, greater justice. I don’t know; I’m not hopeful, but I hold out hope. Rather than disavow our shared vulnerability or accept unequal distribution of suffering as inevitable, maybe we can move toward repair.

Bury: Can you talk about agency in relation to climate and constraint? There’s a stanza in “DAVID (W)” that stands out in this regard: “A story about car culture/ A story about the backseat feeling of an oncoming crash/ A story about backseat theory/ a theory of childhood during climate change.”

Sullivan: When it comes to climate change, I think that one can’t do very much as an individual, but one should still do everything possible. In practical terms, I co-direct the NYC Climate Justice Hub, a community-university partnership between CUNY and NYC-EJA ( New York City Environmental Justice Alliance). We build cross-sectoral infrastructure to support frontline climate justice. This initiative unites three of my main preoccupations: higher education access, environmental justice, and New York City. I also have a public art practice with Mare Liberum, a boat-building art collective, that enables me to develop projects with waterfront communities.

Bury: How do you balance your roles not only as an activist, writer, and cultural worker but also as a parent and partner? Your son, Demitri, makes multiple charming appearances in Reps.

Sullivan: It’s tough because I believe that climate change demands individuals slow down and reduce their life outputs. Yet at the same time I feel compelled by both internal and external pressures, particularly the neoliberal university’s scarcity dynamics, to perform every minute that I’m awake. I don’t know how to reconcile those two things. How do you do it?

Bury: I overworked myself for ten or fifteen years, squeezing every drop of productivity out of my weeks until I was diagnosed with a medical condition last year that forced me to slow down. I feel clear that I can’t work that way anymore but less clear about what a satisfying balance might look like for me going forward.

Sullivan: One thing I can say is that having a child surprised me with how invigorating it felt. I was suddenly filled with lots of new things to say and new enthusiasm for saying them. Parenting can be exhausting labor but the more I poured into parenthood the more material and motivation I had as a writer and an activist.

Bury: Your book’s third and final section, “Margaret, Are You Grieving?,” is a long poem about your experience at Ground Zero during the September 11th World Trade Center attacks. Did you use any constraints to write this poem?

Sullivan: No. The constraints I used in “Exercises” and “Typology” psychologically prepared me for “Margaret,” which was written for the 20th anniversary of Twin Towers’ fall. I was living downtown when they fell and I suffered PTSD that kept me trapped in a nonprogressive narrative. I had to keep telling the story until I could find my way out of it, which I eventually did.

Bury: What helped you do so?

Sullivan: Many different things, but one I’ve been thinking about lately in relation to poetry is EMDR, which stands for Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing. It can be accomplished by shifting the eyes bilaterally from left to right, but when I did it, I held a small transducer in each hand, and the therapist choreographed a series of electrical pulses alternating sides. The premise is that over time the repetitive stimuli move the memory from the right side of your brain, where the trauma is trapped as a present-tense experience, to the left side, where the hippocampus can process the memory and ultimately put it away. The therapy greases the neural pathways. It’s very mechanical but it worked for me.

Bury: Literary constraints can be mechanical but can also be used to reroute ingrained patterns of behavior.

Sullivan: Though called by other names, these types of repetitive bilateral movements have been used across cultures and times to heal from trauma, whether through big gestures like dance or drumming, or fine motor work like drawing or needlepoint. But real healing only happens in community. Community is a contested term in literary and artistic worlds, often used to exploit social capital, but here I mean groups of people who have something in common, a counterpoint rather than a complement to capitalism. This dynamic maps onto the structure of Reps. In the book’s first section, I used constraints to induce a sense of safety and predictability. In the second section, the writing exercise brought me into closer relation with community members. And the third section is about getting inside my own trauma.

Bury: It sounds like embodied healing processes were important to you both within and beyond the book.

Sullivan: There’s this popularized quote about how trauma is too much, too soon, too fast. A wound leaves its mark in an instant. Healing is ongoing, regular, repetitive: steadiness is its end goal, its goal with no end.