Piece these disjointed images together

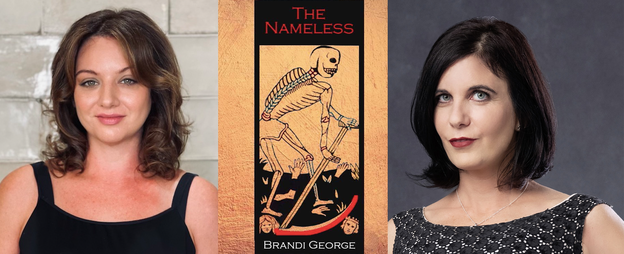

Brandi George in conversation with Sandra Simonds

The Nameless: a memoir-in-verse (http://www.kernpunktpress.com/store/p38/nameless.html), is the winner of the Eyelands Book Award. Brandi’s work explores her struggle with mental illness, sexual assault, religious extremism, an exorcism, and the burning of her creative work when she was in her early teens. Through all of this, she has been guided and inspired by the power of poetry and artmaking. Later, she would also discover Wicca, Zen meditation, and Ashtanga yoga, which helped her to let go of her past and take control of the present moment. Her goal is to teach others to find this same freedom through their creative work, and by connecting to the breath and the body. Her first book of poetry, Gog, (Black Lawrence Press, 2015) won the gold medal in the Florida Book Awards, and her second collection, Faun, (Plays Inverse, 2019) is a play in verse. Her poems have appeared in American Poetry Review, Fence, Orion, Gulf Coast, Prairie Schooner, Best New Poets, Ninth Letter, Columbia Poetry Review, and The Iowa Review. She has been awarded residencies at Hambidge Center for the Arts and the Hill House ISLAND residency, and the Time & Place Award in France. She is currently working on a collection of poem-essays about figures from her dreams and visions, including Michelangelo, Elizabeth Siddal, Virginia Woolf, Salvador Dalí, William Shakespeare, and a bear.

Sandra Simonds: Tell me a little bit about the arc of your writing life, how it has evolved over the years, and how that journey brought you to creating your latest book, The Nameless.

Brandi George: The Nameless is an autobiographical book that uses events from my life as a structure for the narrative. The book evolved from a poetry and dance collaboration with University of Southern Mississippi professor and choreographer Brianna Jahn Malinowski. I credit this as my first step toward thinking about body work as essential to the creative process.

The first section of the book focuses on my early experiences, beginning with my first brush with death at the age of two when a Belgian draft horse tossed me (by his gums) into a stone water trough — and then later an exorcism, the burning of my poems, and an attempted suicide.

And then in the second section, I explore a less dramatic sort of dying, the death of creative connection to myself, others, and the more-than-human world, as I become hyper-competitive and over-focused on external marks of validation, such as publication and professionalization. The narrative is very linear in structure, and it just goes chronologically all the way to the present. Because of all the yoga and meditation I do, I’ve been able to distance myself from a lot of the pain, violence, and trauma that I’ve been through. My spiritual practices, especially yoga, have given me space and a sense of expansiveness.

My life in the book is still highly mythologized, and I’ve been able to be objective about some of the experiences in a new way, although I’ve written about these events many times. You could say that I write the same story over and over, but each time it feels totally new to me. Because, as we know, trauma is stored differently in the brain, and it can be really hard to access it during the writing process. The things that come out when you talk about trauma are often garbled and difficult for readers to comprehend. It takes me a long time to piece these disjointed images together, to create a bridge for the reader to cross over. That’s something I’ve always struggled with. Sometimes people tell me that my poems make them feel alienated or that they are too difficult, and I wanted to create a version of my story that more people could connect to. This is why I decided to use a linear narrative and titles that directly state the plot points of each chapter. I’m trying to find the place of maximum energy or tension, a space where readers won’t feel alienated, but where I won’t lose the organic way that images unfold for me, the way that the natural voice emerges.

Simonds: Can you talk about the book’s title?

George: The idea of naming is something that has fascinated me for a long time. There are so many religious traditions that address the powerful potential of naming. In the biblical mythology, the first man, Adam, begins by naming everything in creation, as if he is summoning each thing from the realm of imagination into the realm of concrete manifestation, as if from a dream into reality. My spouse, Michael, also talks about how the different names of God hold great power. For instance, the entire Torah is said to be the name God, and Jewish mystics would meditate on the names.

And so we’re always trying to put a name on something that is extremely mysterious, something that contains too much complexity for naming. One of my favorite tarot decks, the Marseille Tarot, has this card, #13 (my book’s cover image), which is the only card that doesn’t have a name. It’s often referred to as the Nameless Arcanum. The card is Death, a force that has both infinite names and no name. Although Death is often seen as a scary or destructive force, it also clears a space so new things can emerge. In another paradox, death is essential for creation. Death is generative. When you lean into the idea of death, and you don’t flinch away from it, and you let it guide you, you get to the other side and discover that the divine force is often hidden behind the image of what you fear the most.

Simonds: I would love for you to talk a bit more about the figure of Death and how it is working in this book? Is Death a character, an idea? The central trauma that sets the narrative in motion becomes a catalyst for this fascination with death or is the central trauma a kind of death and rebirth? If so, is Death gendered in your work?

George: The figure of Death is inspired by my real visions and hallucinations. I go into this in more detail in the book, but I’ll summarize it here. I saw Death for the first time when I was six years old in the basement of our house. There was a woodstove with stacks of fungi-covered logs in the corner. A shadowy figure emerged from one of the mushrooms that was stuck to the bark. Thus, my interest in mushrooms and their relationship to the figure of Death was born. The second time, I was severely depressed, and the Angel of Death appeared to me as a winged shadow. The third time, Death appeared as a more traditional image, with a black cloak and skeletal face.

So, like most images in my work, the figure of Death springs from my own experience. And yet, you’re right. It becomes a metaphor as well. As I reimagined my own visions, I saw that I could choose not to be afraid. Instead, I could choose to embrace all aspects of life — the frightening and the beautiful.

And I realized that every extreme contains its opposite. This is why poetry so often contains paradox. The grotesque dwells in the beautiful, and the beautiful in the grotesque. Birth necessitates death. And death clears the way for new things to be born. This is actually something we can be sure of — change will come, old things will die, new things will be born, and we will have no idea how this all unfolds until it happens. Control is an illusion. Embracing death means embracing the unknown, uncertainty, mystery. And this is at the heart of Keats’s negative capability and all that. Embracing death is at the heart of creativity.

Death is also not gendered for me. I experience Death as many genders, but also as a sort of hive or collective. My own gender is experienced this way as well. I feel alternately male, female, multiple beings at once, and sometimes something that doesn’t seem human at all. It’s very hard to explain, but this is why I use “we” throughout the book. “We” is my natural pronoun, although I typically edit it to “I.” For this book, I wanted to be as honest as possible, and that’s something I’m working on as a poet and a thinker. The truth is sacred. I’m not sure why, but telling the truth is so important to our growth, development, and mental health. Although I’m not talking about facts, or literal truth necessarily. Sometimes the emotional truth manifests as fiction, as it did in the Thumbelina sections. Truth is important, but it isn’t always literal. It’s different for every person, and it will manifest differently in each creative piece.

Simonds: The Nameless is a book that feels adamant about taking up all of the space it needs, feels like a book that, from the first urgent utterance, immediately moves beyond the confines of “what can be said in language.” Women are often told that their feelings, emotions, ideas are “excessive.” I’d love for you to talk about the relationship between excess, form, and language.

George: Yes, it is 200 pages long, which is pretty excessive for a book of poetry!

Excess is something that our culture is uncomfortable with. We’re always told to be reasonable, logical, to pull it together, to be quiet, kind, giving, pliable, helpful. We’re asked to swallow our emotions so that we don’t make others uncomfortable. This implies that excess is frightening and subversive. In excess there is the potential to break comfortable modes of thinking and feeling. In excess there is a space for new ideas, new forms, new ways of being in the world, and relating to each other. It’s no wonder that we’re discouraged from excesses of emotion and taking up too much space.

I think of this “excess” as the creative impulse itself. It is the power to manifest a work of art, to form a structure, to mutate, to grow, to connect. And emotion drives everything in a work of art. It pushes us beyond the limitations of our paradigms, our habitual modes of thinking and responding to the world. The feeling is what drives the poetry, and the feeling is what manifests as form and structure—syntactical structure, lineation, and even the movement of the images or narrative. Emotion drives it all. I believe emotion is the language of the spirit. It’s through emotion that we connect to ourselves and find a unique voice (or a particular rhythm of consciousness), to other people, to the more-than-human world, and especially to readers. Emotion facilitates all of this. Emotion leads us as individuals, and through individuals, to the larger community. This all starts with excess.

Simonds: I’d love for you to expand on psychedelia, mushrooms, and visions.

George: I’ll start with visions. I’ve always had those, long before I began experimenting with psychedelics. I didn’t try psychedelic mushrooms for the first time until my mid-twenties. Psychedelics are not “fun” for me. I don’t use them to escape reality or as a curiosity. I think they have deep, profound spiritual potential. On my first mushroom trip, I found a fragment of my soul in the center of a mushroom the size of a dinner plate, and after that, I was able to connect to plants in a way I had never done before. In fact, I credit the inspiration for my second book, Faun, to a white pine tree behind my old house in Tallahassee, but that’s another story.

So, I choose to engage with psychedelics respectfully, ritually, and with a clear intention. I do it in the spirit of growth, transformation, and connection to the more-than-human world. I’m never the same after a trip, and that’s why I don’t engage with psychedelics often. Others may have different experiences than I do, and I respect that. For me, psychedelics open a gateway for nature to speak to us — for all things to speak to us. And this channeling can lead us in new directions in our poetry and in our lives. The more-than-human world facilitates original thought. Just like emotion pushes us outside of our habitual modes of thinking, the more than human world can link us to our emotions and help to push us even further. By writing with and for the world around us, we have the capacity to push ourselves further than we would otherwise be able to.

In my experience, this radical connection can facilitate an increase in creative energy. Psychedelics can help with this, but they are not entirely necessary. You can also simply feel a sense of openness as you walk or sit outside, and this can work for cities as well as forests. There are many ways to connect to the more-than-human world that don’t involve psychedelics. For instance, freewriting is simple, but effective. Personally, I prefer writing in wilderness areas, particularly first-growth forests, because the more-than-human world has been able to exercise its own will and consciousness there (at least to a greater degree than in urban areas or second-growth forests), and when I connect to areas that harbor fewer human inhabitants, I am able to feel a more intense energy and push myself further beyond the limitations of standard conventional thought. Some poets prefer to connect to urban areas, and that can also be very effective. It depends on the person. I would suggest doing a series of experiments with writing in different areas or switch it up periodically. And what works for one book won’t necessarily work for another. There is no right way. Every person has a wholly unique path, and each writer must stay open to all possibilities.

And beyond psychedelia, mushrooms are so important to this earth. Beneath most forests are complex mycorrhizal networks that help trees and plants to share nutrients. Fungi also help to break down matter into reusable forms, and without them, we would be buried in detritus, all of the dead things that ever lived would simply pile up around us. There wouldn’t be any space for new life.

Simonds: How do spells and witchcraft figure in your work? I see both as knowledge that isn’t derived from logic or reason, but possibly passed through familial or alternative traditions that may have been suppressed and might re-emerge in language, particularly poetic language. In my mind, there’s a connection to the idea of a suppressed power, especially with witches and their spells, forming a feminist argument against patriarchal attempts to destroy this power. How does this connect to your concept of death as a generative force? It seems like you’re suggesting another realm of power, not explicitly spiritual, but tied to language — central to Jewish mysticism, as you mentioned.

George: I typically resist labels with my spirituality. This is because language (at least English) necessitates binary thinking, and the experience of the divine is so much larger than any words. That said, my spirituality is partially inspired by Wicca, which is a religion that centers around creative expression in connection with the natural world. I’m not an “official” Wiccan, and I don’t practice with a coven (at least not yet). I create my own spells and rituals, which are sometimes based on received forms. I’ve heard this referred to as chaos magick, but call it what you will. Like Wicca, my Ashtanga yoga practice explores the five elements (earth, air, fire, water, and spirit/space), and so they speak to each other very well.

In Sanskrit, like the Hebrew of Jewish mysticism, letters can be gateways to other levels of consciousness, even to the divine. The syllable “aum” or “om” is the sound of the creation of the universe, and the sound of the divine itself. The division between sound and matter dissolves. And because language is sound, it has this potential for physical manifestation.

Colonization and patriarchy depend on the repression of language. The language of the colonized is often prohibited and actively outlawed, particularly in schools. That’s one way that languages die, but when they die, where do they go? One might argue that all things that ever existed are still with us, the depth beneath what we see, the invisible haunting the visible. The ghosts of languages manifest in the etymology of words, in the names of rivers and mountains, or they breathe within the rivers and mountains themselves. How thin is the veil between the visible and invisible? Can we summon them again? I like to think so.

You ask if witchcraft can recover some of what has been repressed or destroyed, especially in relation to women’s power (a feminine energy that all genders may access), and I think your intuition is right. I have been referred to as “demonic” or called a “devil” more times than I can count. It usually happens when I’m subverting authority, speaking my mind, or expressing my creativity. When my parents found my anti-Christian poems, for instance, they called an exorcist. Muse and demon blur, and creative women are regarded with fear and suspicion. At first, I tried to conform to what they wanted. I went to the church camp, and I was baptized. But the more I tried to conform, the more I repressed, the more terrifying my hallucinations became. The only relief I found was in writing poetry (prohibited by my parents) and in exploring alternate modes of spirituality. An exploration of “Pagan” religions was important here. I discovered that what are considered “evil” symbols for Christianity are often recontextualized gods from colonized cultures. For instance, the Devil appears similarly to the pagan god, Pan, and carries a trident like Poseidon or Shiva. The number 13, a cursed number in Christianity, symbolizes transformation and is even considered a lucky number in many cultures. The number may also be associated with femininity and divine feminine energy, partly because there are thirteen lunar months in a year, which corresponds to the female menstrual cycle. If what we repress in our individual lives returns as the shadow, then what we try to destroy as a culture will return as a devil. The Christian hell is teeming with repressed feminine creative potential.

Simonds: This book uses the “natural” world in a way that “denatures” our romantic notions of it, makes it feel dangerous, foreboding. How do you see nature in relationship to the psychological aspects that you are trying to render?

George: As I said before, there are many positive things about working with your environment. However, wilderness areas can be very dangerous as well. Our Romantic notions about nature, seeing only the beauty and not the grotesque, not the dangerous, will put us in danger. If we view our ecosystems in the spirit of a landscape painting, a pretty picture, a flat, dead, superficial resource — then we risk making poor decisions in those spaces.

But more than that, when I was younger, I used nature as a way to process many of the negative emotions I felt. I externalized my trauma, projecting it into the more-than-human world around me as grotesque hallucinations. That’s why it often took on a sinister appearance. When my attitude changed, the world around me also changed. When I stopped being afraid, when I accepted my past, my trauma, my imperfections, and my visions — and just let them be as they were — everything shifted. My perception of nature became more balanced as I became more balanced. It is wild how much our psychological states change the way we view the world.

If we focus too much on only the positive or pleasant, only our joy or happiness, then we repress some very important aspects of ourselves. As I said before, these repressed parts of ourselves don’t go away, they hide in the subconscious, in the body, and they emerge even stronger the next time. Poetry can engage these rejected or repressed aspects of ourselves and the world. It can allow them to manifest in a safe space, and hopefully, it can help to integrate the shadow, the unconscious, back into consciousness mind. It is that same paradox I referred to earlier, the conscious mind representing life, and the unconscious representing death perhaps. The two need each other, and one can’t exist without the other.

Simonds: We live in a world where creativity is so undervalued. The experiences you went through as a child, especially the exorcism, seem like a way to try to kill the spirit. But somehow poetry is an excess, just like a spring or something that just keeps coming out that there there’s no way to kill it. I see you as a kind of maximalist poet and I notice in this book and your other books, you are committed to a kind of world building that we see in other genres. We see it in like science fiction or fantasy writing. Some poets do this. William Blake comes to mind immediately as does Milton. I think it’s interesting and rare. Can you talk about that? And maybe your influences?

George: Yeah, I think they really were trying to kill my spirit, to make me “normal” in some way. Calling someone a “devil” or demonizing them is all about power. When you tell someone they are evil for being creative or for being who they are, you are attempting to collapse their complexity, their humanity, and dignity. But we can say no to that. That’s the hilarious thing — we can say no. The spirit is unbreakable.

In a lot of my work, I don’t necessarily think of myself as a poet when I’m writing. I try to give myself as much space and freedom as possible. A lot of my work really starts as fiction or prose (or paintings) and it spins off into poetry in later drafts. I don’t really worry about genre when I’m writing. I just wait until I’m done and then I’m like, what is this? Where could I possibly send this? This is often a difficult question because my final manuscripts are so big.

In terms of the formal elements, with The Nameless, the book really started as a as a fifty sonnet sequence and then it was merged with a more narrative book. My first love was Shakespeare in my early teens, and I carried his Collected Works with me like it was a Book of Shadows. John Keats visits me in my dreams, as does Virginia Woolf. I have also been influenced by William Blake, H.D., Robert Duncan, Gwendolyn Brooks, Allen Ginsberg, Walt Whitman, Lucille Clifton, Anne Carson, Sylvia Plath, Ted Hughes (particularly Crow), Anne Carson, CAConrad, Dante, Annie Finch, Kazim Ali, B.H. Fairchild, dg okpik, Larry Levis, Barbara Hamby, Pablo Neruda, Jody Gladding, Stuart Cooke, Elizabeth Siddall, Sherwin Bitsui, Akka Mahadevi, Lal Ded, Joyelle McSweeney, John Milton, Federico García Lorca — and I could go on and on. There are so many more poets who I owe a great debt to!

Simonds: Who are your contemporary influences?

George: Anne Carson is a big one. She was one of the first poets who made me understand what was possible in poetry — the liberation of the confines of genre and medium. And her book, Autobiography of Red, taught me a lot about worldbuilding in poetry. Stuart Cook, the author of Lyre, gives space and respect to the more-than-human world, giving them pronouns and allowing them center stage. CAConrad’s notion of the “extreme present” helped me to understand the importance being present in the body during the creative process, of how to create an embodied and sustainable writing practice. Sherwin Bitsui is a poet who uses images in a very evocative way. He seems to be able to, as I was talking about before, summon language from the invisible world. Annie Finch’s poems and her Poetry Witch community have also been important for me. Finch correlates poetic meters to the five elements in a way that has helped me to merge my spiritual practice with my poetry practice.

Simonds: You are so engaged in so many different vibrant art forms. Where do you see your work going from here?

George: Things are going in a couple of directions. First, I’m working on this series of poem-essays, or essays that go back and forth between poetry and prose (inspired by Dante’s La Vita Nuova). It started with an experience I had in Florence last summer. I was writing at my kitchen table when I had a vision of Michelangelo — not Dante (because that would make too much sense). I fell out of my chair and scrambled around trying to find a pen and paper, and I drafted the basic structure that the poem-essay would take. I like how the prose writing grounds my poetry (a continuing concern for me), and I find that the prose sections allow for a greater range of tone and diction. I’m also collaborating with one of my colleagues at FSW, musician and Humanities professor Elijah Pritchett. We’re mucking around in the space between literature and music, just experimenting with different sounds. I’m also thinking about ways to help myself and others create a more embodied writing practice, going to various Ashtanga yoga workshops and retreats. I’m building some ideas about yoga and poetry writing, but it’s a long process. I know that whatever happens, it will be totally, completely, incomprehensibly, unpredictable.