State-of-the-Nation poems (5)

Kendrick Smithyman, ‘If I Stepped Outside, in May ’93’ (2002)

My good friend and fellow-poet David Howard writes in to question my use of the epithet “unquestioned Top Bard” for Bill Manhire in my previous post. He also comments that “we weren't 'all' lost in the postmodern forest of the 1980s” …

I did wonder (as I said in my reply to him) if anyone would react to my canonisation of Manhire:

I can't say I think Top Bard an enviable job, but it does seem to me to have passed from Rex Fairburn to Allen Curnow in the 50s, and thence to Bill Manhire in the 2000s -- I'm speaking of influence and cultural dominance, you understand, not necessarily poetic merit ...

And as for those thickets, I guess I was thinking more of Academics than poets (the principal audience for the website). Again, meant to be a bit teasing ...

So I think I’d stand by the description. It doesn’t equate with saying that Bill Manhire is the best poet in the country (though I myself would certainly put him among the very best) – such value judgments are too fickle to depend on. What I am saying is that he’s overwhelmingly the most important in terms of “culture-power.”

What I am rather more embarrassed by is the fact that I appear to have misdated Ian Wedde’s “Barbary Coast” – while it was indeed included in his 1993 book The Drummer, it was actually reprinted there from an earlier volume, Tendering (1988). Never mind. It’s clearly a poem about the 1980s, which was the reason for including it in the first place.

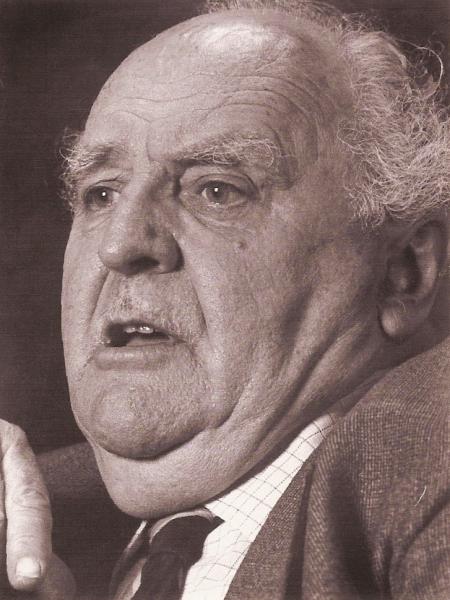

In any case, this oversight gives me an excuse to do a bit more fancy footwork with the dates. When meditating the 1990s, I remembered this piece, by the late great Kendrick Smithyman, our Kaipara Cavafy, our Northcote Neruda (seen here in a photograph by Kenneth Quinn)… Kendrick died in 1995, and this, one of his very last poems, was written in 1993.

It wasn’t actually collected in bookform till Last Poems (2002), though, so I’ve decided to use that as an excuse for including it in my stepladder of poems. After all, I ended up putting in two poems from the 1970s, Baxter’s and Tuwhare’s, so why not two poems about the 1980s, that most feral of decades in New Zealand’s recent history, when the wolves were living on wind in the streets of the city (Que les loups se vivent de vent – Villon), and our fat insular people suddenly felt the icy breath of the outside world?

These, in the day when heaven was falling,

The hour when earth's foundations fled,

Followed their mercenary calling,

And took their wages, and are dead.

Their shoulders held the sky suspended;

They stood, and earth's foundations stay;

What God abandoned, these defended,

And saved the sum of things for pay.

So said A. E. Housman, in his “Epitaph on an Army of Mercenaries,” which has always struck me as one of the wisest and most insightful of all poems about the First World War.

Everything seemed to be for sale in those days. We’d elected, in 1984, what we fondly thought would be another vaguely socialist, vaguely centrist Labour government, only to realize with a shock that the Monetarists had invaded the temple – that these ideologues of the New Right were quite prepared to entertain the notion of no government at all.

Sector after sector fell to their ruthless cost-cutters, one at a time, and the cries of pain rose up on all sides …

Until 1987, that is, when the bubble burst, the Stock Market crash, worse in New Zealand than most other places because virtually anyone could play in our deregulated market, regardless of capital reserves or any financially prudent controls whatsoever.

These, in the day when heaven was falling,

The hour when earth's foundations fled ...

Who am I speaking of? Who “held the sky suspended … / And saved the sum of things for pay”? I guess it was us, really. No heroics, nothing but everyday business, really, but it was our artists, our teachers, our mothers, our family-men, who kept things moving along while the Richard Prebbles and Roger Douglases and other donkeys screeched their nonsense from the Beehive.

Kendrick’s poem comes from the depths of suburbia, but his eschewal of the grand gesture, his quiet acceptance of the small beauties of the everyday are what makes it (for me, at any rate) a perpetual joy:

If I stepped outside there would be no light to surprise

my body making demands.

Without given notice rain surprises, rain tilts headlong

into fall, past rata, past silvery gum, oleander, Norfolk pine,

a few minutes filling spaces which may wait on apology;

they want light at the moment.

One notes the adroit blending of the language of the marketplace (“making demands,” “without given notice”) with the noble names of trees, native and introduced species alike: “rata … silvery gum, oleander, Norfolk pine.”

The poem now shifts gears, moves closer to the heart of its author / protagonist:

I crouch in my cave

under the house, basement solitary. Anachronist,

on the look out:

Not an anarchist (“I am an Antichrist / I am an Anar-chyst” as the Sex Pistols so memorably warbled), but an anachronist: someone out of his time.

That description of Kendrick's cave of making is only too accurate, actually. I spent many hours down in that basement, with his wife Margaret Edgcumbe’s permission, looking through the immense series of boxfiles which constituted his life-work (they’re now in Special Collections in the Auckland University Library).

it cannot be like this downtown in the city.

Mirrorglass towers squinting all ways into themselves

discover they are heartless, at best coldhearted,

never forthright, only arrogant. Darkness at noon.

My God, how they raped and pillaged our city in the deregulated 80s! It was like the unleashing of the Jacquerie, or the Sans-culottes of the French Revolution. What had been a pleasant – if not particularly distinguished – colonial city became a nightmare of building sites and mirror facades.

Why this mania for reflection where there had been none? Why did they all resort to mirrorglass as the architectural dernier cri? Were they conscious of their own poisonous vapidity, their lack of substance? Did they realize that any memorable images would have to be lent from elsewhere? We literally had to link hands in front of it to save the Civic Theatre from the wrecking ball. A cunning developer managed to gazump everyone and tear down His Majesty’s Theatre during a long weekend – then promptly went bust and left a huge pit where a treasure had been.

Who will expect a veil of a temple to be rent,

the money makers driven out? Showers lacking any winds

to play at motives

give up and go away. We simply guess at what happens

between one investment opportunity and its others

as their murk, pulsing, stands brightened.

Kendrick knows that we can’t expect a Deus ex Machina to save us from the consequences of our own folly every time. Christ drove out the moneylenders in order to teach us how to do the same. We haven’t learnt our lesson sufficiently well to expect a repetition.

Market reports are broadcast, stocks look good

for those with a knowledgeable eye. Nothing goes

visibly traded between pine, lemon and silver dollar.

When I go outside light flows, pure enterprise.

“Nothing goes / visibly traded” – but an exchange is taking place nevertheless: light, water, soil combining into life and energy.

The poem’s rebuke is most telling because it’s not pompous. Kendrick was never afraid of a pun, and he doesn’t see them as detracting from a heartfelt message. The “pure enterprise” of photosynthesis just is more impressive and more interesting than that pathetic crawling heap of traders “yelling like beasts on the floor of the Bourse” (as W. H. Auden put it in his elegy for W. B. Yeats).

That we’ve allowed them free rein is our shame. The trees refute their dark dogmas without even trying. How can it be that twenty years on we’ve allowed the whole madness to happen again? Do we never learn?

Apparently not. Hence the continuing need for one of the very last poems that Kendrick Smithyman, one of the enduring masters of New Zealand poetry, ever wrote.

Notes on NZ poetry