State-of-the-Nation poems (2)

James K. Baxter, ‘Ode to Auckland’ (1972)

If the Allen Curnow poem I talked about in my latest post looks back on the fifties, that whole post-war “You’ve never had it so good” period, then it seems logical to go on to discuss further “state-of-the-nation” poems commenting successively on the sixties, the seventies, the eighties, the nineties, and (finally) the twenty-tens.

This is the list I’ve come up with. Not all the dates fit perfectly, but at least it provides some sort of a coverage of styles, ideas, voices and views, over the last fifty years of New Zealand poetry. Each one of them will take a fair amount of contextualising and unpacking, but it’s the only way I can think of to give you a reasonable overview of where we’ve been and where (possibly) we might be going.

It’s not (I hasten to add) that I have a particular predilection for poetry’s oracular role, but I think I do see a certain necessity – at times – for a writer to assume the robes of Tribune of the People. In any case, they (we?) do, and it can be quite interesting to see just how they square this with other aspects of their artistic practice.

I’ve dated each poem according to its first book appearance, rather than date of composition (where that can be ascertained), as befits their status as “public poetry” (not, I’m sure, that all of these authors would agree with that definition of their work):

[1950s:] Allen Curnow (1911-2001): “A Small Room with Large Windows.” In A Small Room with Large Windows: Selected Poems (1962)

[1960s:] James K. Baxter (1926-1973): “Ode to Auckland.” In Ode to Auckland (1972)

[1970s:] Cilla McQueen (1949- ): “Living Here.” In Homing In (1982)

[1980s:] Ian Wedde (1946- ): “Barbary Coast.” In The Drummer (1993)

[1990s:] Kendrick Smithyman (1922-1995): “If I Stepped Outside, in May ’93.” In Last Poems (2002)

[2000s:] Michele Leggott (1956- ): “peri poietikes / about poetry.” In Mirabile Dictu (2009)

*

In many ways New Zealand poetry is still reeling from the impact of James K. Baxter. He occupies a position somewhat analogous to that of Robert Burns in Scottish literature (a comparison I suspect he would have relished): a towering genius who could never quite reconcile himself to the laws and manners of the rest of society.

He began as a teenage wunderkind, his early poems being included in the second edition of Allen Curnow’s epoch-making Book of New Zealand Verse (1945, rev. ed. 1951, final apotheosis as the Penguin Book of New Zealand Verse in 1960). He ended as a kind of social and religious revolutionary, having founded a commune at the tiny settlement of Jerusalem on the Whanganui River, where he wrote some of his very finest poetry – the Jerusalem Sonnets (1970), Jerusalem Daybook (1971) and Autumn Testament (1972).

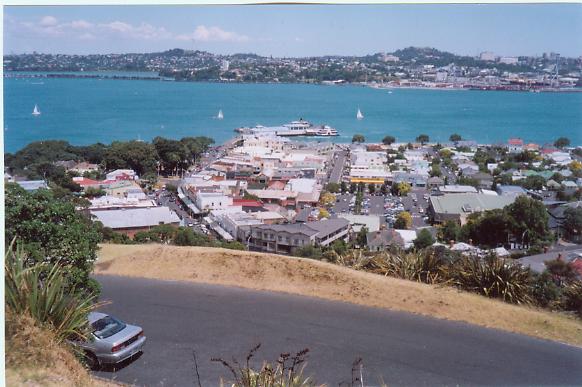

“Ode to Auckland” dates to the period just after that, when the commune had been broken up (at least temporarily), and he was living at a bit of a loose end in our largest city, Auckland. The poem opens with scant ceremony:

Auckland, you great arsehole,

Some things I like about you

Some things I cannot like.

And what are some of these things he “cannot like”?

The sound of the opening and shutting of bankbooks.

The thudding of refrigerator doors,

The ripsaw voices of Glen Eden mothers yelling at their children,

The chugging noise of masturbation from the bedrooms of the bourgeoisie,

The voices of dead teachers droning in dead classrooms,

The TV voice of Mr Muldoon,

The farting noise of the trucks that grind their way down Queen Street

Has drowned forever the song of Tangaroa on a thousand beaches,

The sound of the wind among the green volcanoes,

And the whisper of the human heart.

New Zealand is one of those countries divided in two halves. Just as, in Australia, Sydney is locked in perpetual battle with Melbourne; in Scotland, Edinburgh with Glasgow; in Brazil, Rio de Janeiro with Sao Paulo; so in New Zealand, Auckland is thought to be a sink of iniquity and cosmopolitan pretension running roughshod over the solider values of the rest of New Zealand. It’s Heartland (which, strangely, seems somehow to include the other large cities, including our politician-&-bureaucrat-infested capital Wellington) against Auckland all the way.

Many have therefore taken comfort from these lines of Baxter’s (a native of the south of the South Island) and the way in which they lay the blame for our land’s ills squarely at Auckland’s door (“Mr. Muldoon,” by the way, was a particularly loathsome ex-Prime Minister of ours, who ruled the country in dictatorial fashion between 1975 and 1984).

Few of these casual readers of “Ode to Auckland” bother to read on:

Boredom is the essence of your death,

I would take a trip to another town

Except that the other towns resemble you exactly.

Oh. Okay. It seems that it isn’t just Auckland he’s talking about, then:

How can I live in a country where the towns are made like coffins

And the rich are eating the flesh of the poor

Without even knowing it?

It’s almost inconceivable now just how wicked the next four lines sounded at the time (I should know, having been ten years old at the time). You mean to say that you actually take drugs, Mr. Baxter?

Auckland, even when I am well stoned

On a tab of LSD or on Indian grass

You still look to me like an elephant’s arsehole

Surrounded with blue-black haemorrhoids.

Not a bad bit of impromptu word-painting there. Most of our towns are still surrounded by a scurf of garishly painted industrial warehouses and thinly described rubbish dumps to this day. It’s an angry poem, a disgusted poem, the poem of a man at the end of his tether (he was dead – mainly of exhaustion, it seems, though the official cause was a bad heart – within a few months of writing it).

This next bit didn’t exactly endear him to the local conservatives, either (you have to remember that the Vietnam war was still going on at the time: a constant drip-drip-drip of death on our television screens every night):

O Father Lenin, help us in our great need!

The people seem to enjoy building the pyramids.

Moses would get a mighty cold reception.

They’d kiss the arse of Pharaoh any day of the week

For a pat on the head and a dollar note.

Like “A Small Room with Large Windows,” I use this poem in class sometimes, too. Last time we discussed it, I remember that its last few lines were described by one of the younger students as “creepy”. I don’t know. You decide:

At another time in another place

Among the Ngati-Whatua

When they brought the dead child into the meeting house

She opened her eyes and smiled.

I guess my problem is that I can’t read them out loud without wanting to burst into tears. They seem to me among the most beautiful and moving words I’ve ever encountered.

“Ode to Auckland,” for all its satire and casual blasphemies, has the biggest heart of any New Zealand poem I know. Maybe we still have a chance of reviving “the song of Tangaroa on a thousand beaches, / The sound of the wind among the green volcanoes, / And the whisper of the human heart.”

Notes on NZ poetry