Coda

A question of faith

Michele Leggott’s poem “shore space, ” from her 2009 book Mirabile Dictu, imagines 1930s New Zealand writer Robin Hyde taking a bus trip through Auckland’s North Shore, and running into various groups of local writers as she does so:

she would be pleased

this spring afternoon above the bays

where gorse and mangroves present

a united front and choko vines run wild

she would be pleased to see Jack Ross

and friends rolling in with a box of books

and a sausage sizzle to do a fundraiser

for a poet who has run out of cornflakes

on the other side of the world Robin Hyde

is living on baked beans and disprins

soon she will leave the places we can see

and walk the seaward road that glistens

with disappearances

It’s a pleasant pastoral vision of friends and collaborators falling over each other to help out, be supportive, advance the art of poetry in an atmosphere of mutual good will.

Would it were so indeed! At first reading, Michele’s poem seems to ignore the actual antagonisms, jealousies, pettinesses etc. that so distinguish our writing lives. Or does it? Robin Hyde — whose collected poems Michele has edited as Young Knowledge (AUP, 2003) — was anything but a tranquil character, in lifestyle, friendships, or literary opinionatedness.

The “seaward road” that she’s about to walk, in fact, will lead her to the frontlines of the Sino-Japanese war in Manchuria (the subject-matter of her 1939 travel book Dragon Rampant) and thence to London and her eventual suicide later in the year, partially — we’re told — as the result of depression at the thought of the oncoming European war.

Michele’s poem may sound superficially lighthearted, then, but it masks a deeper zone of avoidance, fending off the darkness that so besets the souls of the inhabitants of our fortunate isles (or so one is forced to conclude from the pronounced tendency towards the Gothic in our literary sensibilities).

How, then, should I conclude this series of notes on NZ poetry? Well, first of all by acknowledging freely that they’re bound to irritate a great many of my compatriots — the mere fact that I come from Auckland, our largest city, being enough to damn me in the eyes of some.

The (alleged) metropolitan bias that’s bound to give me will be sufficient to explain my faulty choice of writers to celebrate, poems to discuss, and genres to cover. One can’t, in fact, win — which is a pretty good reason for just going ahead and asserting some loud and shameless opinions, I think.

But I know in advance that my views will be met with the usual response to be expected in our islands (“interesting failure to adapt on islands,” as Curnow puts it inhis sonnet about the Moa), that is — silence.

If you don’t want to discuss something here in New Zealand — simple: just stay silent. If some inconvenient points have been raised — ignore them, and they may well go away. If there’s a book / poem / novel that doesn’t fit the approved guidelines — don’t review or notice it at all. Our tendency to emulate the ostrich's response to possible trouble on the horizon is possibly the most irritating aspect of cultural life in this country.

Not that there’s any need for unpleasantness, mind you. Most New Zealanders (myself included) detest unpleasantness. We don’t like strongly held opinions, since it verges on rudeness here to argue too passionately for any point of view (rather analogous to Jane Austen's strictures on the dangers of unbridled “enthusiasm” ... )

Which is not to say that we’re not strongly opinionated and prejudiced in our deeper selves. Refusing to acknowledge that fact does, however, absolve us from having to take any responsibility for the institutionalized racism, sexism and anti-intellectualism so characteristic of the mainstream thought of our nation (check out the “comments” or opinion section on any of our major news websites if you doubt me).

All of which is beginning to sound like a bit of a rant (another unpopular genre in these parts). And I really don’t mean to be unpleasant about it. What I do want to do is celebrate those writers, thinkers, public figures who so passionately combat this conspiracy of silence, of refusal to examine our subconscious motivations, year after year, in article after article, gab-fest after gab-fest, and (yes) poem after poem.

Take David Eggleton, for example, self-styled "Kiwi ranter" and magnificently combative poet and writer, whose new role as editor of our longest running literary magazine, Landfall, places him right at the centre of our cultural life. Has that muzzled him or toned him down in any way? No. Instead, he’s recently set up an online reviews site for the magazine to cover some of the many important books there’s no space to write about within the pages of the print publication.

Now that’s a real contribution to our cultural life. David doesn’t want to ignore inconvenient books and publications, he wants to review them and drag our questions and (possible) reservations about them out into the light.

It may seem invidious to single out a few people from so many, but Michele Leggott, too, with her ethos of “everything for free” and “everything publically available online” — exemplified in the whole nzepc website, its author pages, and (particularly) its feature section — has quite simply refused to shut up about her tastes and preferences. And, rather than try to shut up others, she’s offered them a forum to present their work in its most elaborated and technologically innovative form.

So many heroes, so many editors of online magazines, print magazines, reviews sections of newspapers and academic journals. We’re a talkative bunch, we New Zealanders, for all we cultivate a reputation as taciturn, tongue-tied, inchoate. No, given a chance, we’re as eloquent and unstoppably garrulous as a clutch of Dubliners.

You get the idea, anyway. My agreement with Jacket2 gave me three months to run this column, and I’ve tried to employ that time to best advantage, trying to see things through an outsider’s eyes, trying to manage a cook’s tour of the last fifty years of our poetry while (of course) being conscious of the impossibility of the task.

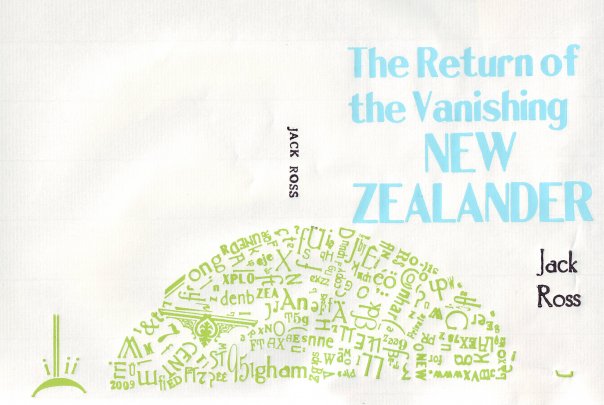

In that ongoing spirit of audacity and hybris, then, I thought I’d conclude with one of my own poems, “A Question of Faith,” from a little chapbook called The Return of the Vanishing New Zealander, published by the (now unfortunately defunct) Dunedin-based indie publisher Kilmog Press in 2009.

It is, I suppose, in its way, my own attempt at a “state of the nation” message, though I was (of course) unconscious of that when I first wrote it in 2003. The original version of the poem, interestingly enough, was dedicated to my friend and colleague Mary Paul, whose edition of Robin Hyde's hitherto unpublished autobiographical writings, Your Unselfish Kindness, has just appeared from the University of Otago Press:

Things don’t always

stay with you

because they’re good

that moment

for example

when the needle

slipped

car stalled

in heavy traffic

walking

with a phone

in one hand

talking to the air

boy wearing BOOM

girl scales

the concrete parapet

clap hands

push pram

the evening draws in

roiled clouds

under the Protection

let the children pass

Under the Protection — a phrase I borrowed from the late great Charles Williams — to you all, then. Let the children pass.

Notes on NZ poetry