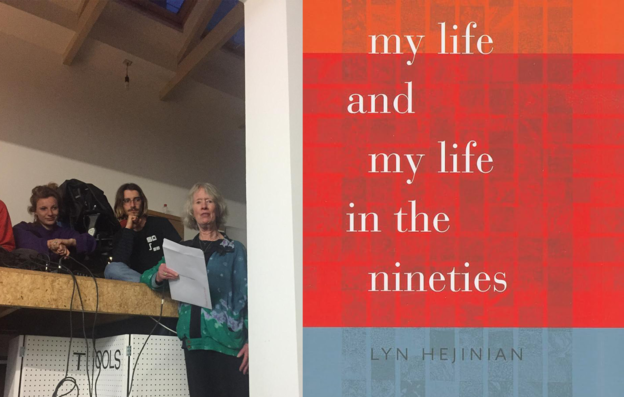

My life in 1994

Though I’d heard of the book before (and of the mysterious movement, Language writing), I first read Lyn Hejinian’s My Life in the Morrison poetry room in Berkeley’s Doe Library sometime early in 1994. The one thousand nine-hundred and eighty sentences of the Sun and Moon edition had a weird effect on me: their detail and complexity were so intense that to encounter them (and this was true even when I reread them later), was always to lose large sections, and thus to be left with a partial pattern almost irresponsibly excised from the greater whole. But this very discrepancy between focus and field also seemed to be one of her basic and generative inventions: by treating each sentence as a somewhat inward-turning pursuit of experiential complexity rather than a player for team rhetorical continuity, she not only took us farther into each individual unit in her modular book, but also forced us to pause and consider exactly which kind of logic we might want to enlist in order to take any new sentence unit as a continuation of the last one. It was as if we had to keep pausing to prop up sticks or mark trunks to remind ourselves of our path at each of the trail forks we encountered in this fantastic new landscape.

Unlike any poetry I’d read before — even my favorite New York School writers — My Life addressed me in a tone that seemed comfortable with the world of philosophy and theory that was partly driving my decision to go to graduate school. But it was in no way reducible to that world, and it had none of the defensive ticks that were then easier to notice in “creative writing,” when the field was more clearly quarantined from theory. But Hejinian’s tone, and her vocabulary, were not an illustration of something I’d already learned; they were the correlate of a mental voraciousness that took on and far exceeded any configuration of intellectual history I knew. It became clear even from this one book that Hejinian was interested in testing and exploring propositions, in seeing where they would lead, and not simply in affirming or referencing authoritative ideas. Just a few months later I learned that she would be teaching a poetry writing seminar at Berkeley the following fall. I had finished my coursework that spring, but decided to enroll anyway.

Over the summer I co-taught my first stand-alone course as a graduate student, in which I proposed to lead a section on experimental poetry that would join my new fascinations to my old. But, as my section of the course progressed, I could tell the senior instructor was getting increasingly uncomfortable: by the time we got to Hejinian and Barrett Watten, exasperated hand gestures were giving way to audible muttering. I was essentially being heckled by my colleague. When I finished, thinking to ease the situation, I said something like, “Well, the course is yours again,” to which she quipped: “What’s left of it!” I now hear in this desperate snarl the highest praise for these two Language writers: they actually succeeded in boring a hole through my colleague’s Truman Show diorama of serious literature. Of course I wanted to climb through as well.

The next fall, in Lyn’s “Serial Theory” course, I began. She wasn’t the first to have alerted me to the fascinating territory beyond the gates of official literature. But Lyn brought the possibilities of this territory to life far more vividly than anyone else ever had. The work she was interested in was not simply negating oppressive conventions (that familiar throat-clearing in criticism about the avant-garde that usually forgets what comes next). The poems were exploring how the serial form — the larger project — could allow poets to think in new ways. Lyn was also the teacher and poet who most powerfully suggested that the great age of these projects was in no way over, and that they could be undertaken by mortals like myself.

“Serial theory” took place in a room on the north side of the third floor of Wheeler Hall, a building where, almost thirty years earlier, Charles Olson had turned his lecture at the 1965 Berkeley Poetry Conference into a piece of performance art that involved keeping the floor and elaborating his (perhaps equally hole-boring, if also, by the end of the third hour, also boring-boring) cosmology to an audience that was kept both from intervening and from leaving; the first to attempt escape was, in fact, ruthlessly heckled by the poet. Hejinian’s class was slightly different. Speaking did not involve rising in challenge and rushing the stage with the hope of prying the microphone out of her hand. There was of course no mic, and no stage. And yet the success of her class was not about exorcising such demons; I remember her being quite curious about forms of acting out in the context of art and poetry, if also extremely polite. Nor did she entirely cede her authority. Differences of opinion and judgment were accepted and even cultivated. But Lyn also modeled an unmistakable rigor and concision that made demands. One got the sense, despite her rather extravagant generosity, that long-windedness, self-indulgence and lack of attention to detail were even more of an irritating waste of time in her class than they might have been elsewhere. This is because time in this room, with this person, was such a precious commodity; it was simply not to be wasted. This would abbreviate our incredible discussions: of Dewey, Emerson, and Lyotard; of the work we were writing; of figures new and amazing to me, like Francis Ponge and Clark Coolidge. There was a kind of jaw-dropping inventiveness to the discussion. As befitting a class called serial theory, the emphasis was not on discrete poems, but on articulating areas of inquiry and ways of working at larger scales.

What was perhaps most striking — especially given the more or less world-changing character of her poetry — was that when she was speaking, the topic was not simply or immediately her own cosmology. Indeed, her writing barely came up, and was in any case not the implied vanishing point of our thinking. Rather, Hejinian demonstrated modes of generative attention and intellectual invention (most often occurring in real time, in front of us, as responses to contingent developments in the class, rather than, say, as planned remarks on her favorite authors). What we did with this, where we took it, was up to us. I say this because a key feature of her thinking and teaching was that it was young writers’ responsibility (and opportunity) to create the context in which their work would have meaning. This is as opposed to writing quietly in isolation and then sending the results to famous editors or authority figures who might welcome one into official culture. But there was also the more subtle sense that the writing scene of which she had been a part was at a transitional moment, and that whatever had been happening in the Bay Area would need to be reimagined, reinvented.

It's no small accomplishment to transform a room full of students into an ongoing community of writers. In this sense, the implausible comparison with Olson is also real. Perhaps interest in Lyn’s work had made this group slightly more self-selecting than it might otherwise have been, but whatever the case, I emerged from this class with both a totally reinvigorated relation to my own daily writing, and with a close set of interlocutors: Alex Cory, Pamela Lu, Adam DeGraff, Greg Biglieri, Faith Barrett, Ann Simon, Travis Ortiz, among them. We wrote regularly and shared our work with one another. We went to readings together. We launched several discussion groups, including one with Lyn. We started a poetics workshop hosted, I think, by Intersection for the Arts. Most of us began presses and reading series. We took seriously the problem of figuring out who our contemporaries were, and how our own thinking differed from that of our teachers. To this end, we made connections with poets in San Francisco and around the Bay Area — Renee Gladman, Anselm and Edmund Berrigan, Mary Burger, Dale Smith, Hoa Nguyen, David Larsen, Eugene Ostashevsky, and Rodrigo Toscano, among many others.

Though the poets I met in “Serial Theory” had been mobilized by Lyn, most of the work in this circle was not outwardly disjunctive in ways that seemed immediately traceable to Language writing. This was certainly not because we rejected that work, or wanted to return to old-time expressivity. We were just exploring slightly different things: Alex was experimenting with tape-recording poetry, often operating below the threshold of the word; Pam was working on Pamela: A Novel; Renee on what would become her first chapbook, Arlem (which the press I was involved with, Idiom, brought out). Ann Veronica Simon (who died young, in 2003) was writing the pieces that would later be collected in This Layer of Plush; and Adam DeGraff was composing the poems in No Man’s Sleep and the odd prose (of deformed literary authority) that we would publish in the first issue of Shark, the journal I co-edited with Emilie Clark.

What emerged, and didn’t emerge, in this nascent — and relatively brief — community of post-Language writers would require another essay. But one way the increasingly important dynamics of the literary community began to register in my writing at the time was in my dissertation on Frank O’Hara: I wanted to find a way to discuss “community” without relegating it to background or mere context. As Alex Cory said at the time, “I like poetry that has friends.” Not just poets but poetry as well. While I was thinking about how this happened in the New York School, I was also reading Lyn’s essay “Who is Speaking?” She framed the problem in ways that synched with my own experience in the San Francisco scene: any literary community worthy of real interest affected the writing undertaken within it at a level that transcended mere support and bled into dialogue and even challenges. I’ve mentioned the ways I was challenged; a final word about her support and friendship. Lyn would publish my first perfect bound book, Cable Factory 20, in 1999 and I would read and comment on the drafts of all of her essays in The Language of Inquiry before it came out in 2000. By that time, however, I was living in New York City, and this not because I had any offer to teach, but rather mostly because Emilie was finishing the monoprints for a collaboration with Lyn, The Traveler and the Hill and the Hill, which was being printed in New York. But I am starting to stray beyond 1994.

Edited byMargaret Ronda Jennifer Scappettone Mia You Julie Carr