Robert Duncan’s dream school

Application

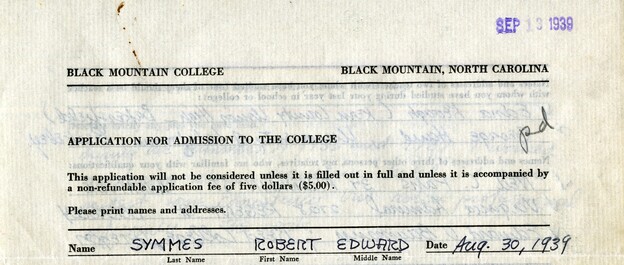

In the late summer of 1939, Robert Duncan (then still using the name Robert Symmes) requested application blanks from Black Mountain College (BMC). Duncan had already finished two years at the University of California, Berkeley, but his plans to continue his undergraduate studies were vague. His $90 monthly allowance from his mother was contingent on completing a degree, so he sent off transcripts to universities while living on the East Coast with his lover, Ned Fahs. After reading an article about Black Mountain in Time Magazine, he sent a letter asking for more information. The now famed experimental school was, in 1939, still relatively new and unstoried — and Duncan had no personal connections there. But the ‘Time’ article described Black Mountain as an “Eden … unencumbered by the machinery of curricular and extracurricular activities” and dedicated to “community living.” Perhaps it was the magazine’s claim that Black Mountain “resembles no other college in the U.S.” that drew in the young poet — only confirming his sense that, as he would later express in his application, traditional universities were places where poems were only preserved. Black Mountain was a place where poems were made.[1]

Shortly after contacting the Black Mountain College registrar’s office, Duncan received instructions from Frederick Mangold, a Professor of Romance Languages and acting College Secretary, to meet up with BMC student George Randell in Oakland for a required in-person interview.[2] After presumably meeting with Randell and submitting his application in late August or early September 1939, Duncan made plans for a mid-September visit to North Carolina.[3] His visit to the first Black Mountain campus at the YMCA Blue Ridge Assembly only increased his desire to attend. “After visiting the College I am even more frantic about being able to study there,” Duncan scrawled in a handwritten note to registrar Anne Mangold. “Originally I was content that the College offered me an opportunity to work on my poetry and at the same time satisfy my mother by going to college–but now after sitting on classes and seeing the students living and studying I begin to realize that you’ve ‘got something.’ Hence a tendency to want to ‘woo’ the College–to beg, borrow, or steal my way in.”[4] An iconoclastic young writer disillusioned with traditional university education and whose apartment walls were tacked with magazine cut-outs of modern art, Duncan was surely the kind of student the BMC founders had in mind when, in 1933, they left their posts at Rollins College to open an arts-centered school free from grades, curricular requirements, and administrative hierarchy. But, in mid-September 1939, just a few days after his visit, Duncan received notice that his application was rejected. To make matters worse, he had boarded the train home without his luggage. So, the disappointing affair was prolonged by a week-long search of the Asheville post office and train station for his suitcase and canvas carry-on bag of clothing. The BMC student file labeled “Symmes, Robert” was closed once receipt of the luggage was confirmed by the Railway Express Agency (fig. 1).[5]

Figure 1. Railway Express Agency Luggage Receipt from Robert Duncan’s Black Mountain College Student File, October 13, 1939. Image courtesy of State of North Carolina Western Regional Archives.

Duncan’s BMC student file, tucked among numerous rejected Black Mountain College applications housed at the State of North Carolina Western Regional Archives (WRA), have, until recently, been unavailable to researchers. Duncan’s file — which includes his correspondence with College administrators, his completed application blanks and supplementary application materials, writing samples, letters of recommendation, and even his luggage receipts — provides new contexts for this specific moment in Duncan’s early biography. While Duncan scholars have long been aware of his early rejection from the College, the primary extant account was a typescript titled “Black Mountain College” authored by Duncan and published online in a 2005 Jacket feature and in print in a 2017/2017 issue of Appalachian Journal, with contextual apparatus by James Maynard.[6] The typescript mostly details Duncan’s return to Black Mountain College to visit Charles Olson and to serve on the faculty, though it briefly recalls his earlier rejection. “I had not been there [Black Mountain] since sometime in 1938,” he wrote, “when, having written from Berkeley I received an acceptance as a student and, as I remember, a part scholarship, and, precariously, set out, arriving there late one night, only to be turned away the following day, firmly, with the notification by the instructor who had welcomed me that I was found to be emotionally unfit.”[7]

Recently, scholars have attempted to expand the purview of Black Mountain poetry by making available the work of unknown and understudied writers associated with the College. Such new work has complicated the identification of Black Mountain poetry with the group of poets included under that rubric in Donald Allen’s The New American Poetry, 1945–1960. For example, the 2019 anthology Black Mountain Poems, edited by Jonathan Creasy, turns attention to poets such as Josef Albers, Buckminster Fuller, and Mary Caroline (M.C.) Richards that, as Creasy writes, “have more to do with Black Mountain than some of those who appear in ‘The New American Poetry.’”[8] The forthcoming Anthology of Black Mountain College Poetry provides an even more comprehensive portrait of Black Mountain poetry than Creasy’s volume. Edited by Blake Hobby, Alessandro Porco, and Joseph Bathanti, the collection recovers a range of student and faculty writers whose aesthetically diverse poems counter predominant narratives of Black Mountain poetry that, even when they focus on the writing communities formed at the College, center Charles Olson’s 1951 arrival on the BMC campus and privilege the aesthetic principles of field composition. Such archival and editorial work complements recent historical scholarship, such as David Silver’s forthcoming “The Farm at Black Mountain College,” which illuminates the day-to-day operations of the College and the contributions of a range of students.

The ongoing recovery of diverse writers associated with Black Mountain will continue to transform scholarly understandings of Black Mountain poetry and its legacies. The story of an aspiring poet’s disappointing rejection that unfolds in Duncan’s student file is not, of course, one such tale. As is well known, Duncan eventually served on the Black Mountain College faculty: teaching craft courses in poetry and enlivening the College’s theater program in its final years through productions of his original plays. When BMC collapsed in 1956, Duncan served as the primary bridge between the Black Mountain and San Francisco art scenes. His play Medea at Kolchis was first performed at Black Mountain in 1956; and Duncan, former Black Mountain theater instructor Wes Huss, and a group of Black Mountain students attempted to stage an expanded version in San Francisco in 1958. The first issues of Black Mountain Review included Duncan’s writings and, in 1960, a selection of his poems appeared as part of the “Black Mountain Group” in Allen’s landmark anthology. Indeed, while many Black Mountain students who were granted admission in the thirties have been largely forgotten, Duncan’s name continues to be closely constellated not just with the Black Mountain school of poetry — but with the mythos of Black Mountain College as a hallowed ground for twentieth-century avant-garde experiment.

The story of Robert Duncan’s relationship to Black Mountain College encompasses the college’s early and later years, but it is rarely told from start to finish. Duncan’s student file helps to piece together its beginnings: clarifying some of the events surrounding his rejection and demonstrating just how committed the young Duncan was to attending Black Mountain. The arguments Duncan makes for his admission to the experimental college also anticipate the views of institutional politics and of the university’s role in knowledge production expressed in later works such as “Passages 21: The Multiversity.”[9] At stake in Duncan’s now-open student file is an understanding of the full span of his association with Black Mountain that opens a more nuanced sense of the so-called Black Mountain school and of the stories of poetry composition and community that have been written in its name.

A “NEED for something else”

The Black Mountain College application blanks asked students to list their interests during the past two or three years. While some kept it quite short — one accepted applicant listed simply “modern art, jazz (seriously), the theatre, advertising, Americana, etc.” — Duncan listed several. These included, among other things: “expressionist experiments in prose”; “writing of poetry — its relation to traditions of past cultures, its relation to the contemporary milieu, its relation to ‘modern’ music and art”; “correlative aesthetics”; the “influence of economics and political forms on the individual”; and “personal likes and dislikes — with an advancing area of likes” (fig. 2).[10] Duncan’s “advancing area of likes” was formed in the intellectual crucible of his two-year stint at Berkeley and his first months living on the East Coast. At Berkeley, Duncan was involved in left organizations such as the American Student Union (ASU) and, with Virginia Admiral, edited the magazine Epitaph. In New York, he would befriend Anaïs Nin and become involved in Surrealist circles. It was during these years, as Duncan would later reflect, that he recognized poetry as “his sole and ruling vocation.” He wrote: “Only in this art — at once a dramatic projection and at the same time a magic ritual in which a poet was to come into being — only in this art, it seemd to me could my inner nature unfold. I had no idea what that nature was, it was to be created in my work.”[11]

Figure 2. Excerpt from Robert Duncan’s application to Black Mountain College, August 30, 1939. Image courtesy of State of North Carolina Western Regional Archives.

In a cover letter submitted with his completed application, Duncan shared his plans to visit the campus and explained that Black Mountain would support his poetic vocation because the College offered a “functionalist education” more satisfactory to his “purposes of study” than “the university system of mass education.”[12] Two other letters included in Duncan’s student file explore his disillusionment with higher education, particularly how prescribed courses and methods of study stifle original thought. These letters express his “NEED” — the word appearing in capital letters throughout both — to be educated at a place like Black Mountain. In a letter introducing his sample poems, Duncan recounts that he spent three years “being lost” in an “orthodox educational system” aimed at “the pot-shot accumulation of ‘knowledge’” where students take courses “that stop at 3 units worth with no opportunity for continued study with experienced teachers, of prescribed materials — Geology, American History etc.”[13]

A second letter (fig. 3 & 4) that outlines Duncan’s reasons for wanting — needing — to attend Black Mountain extends his critiques of university education. This letter describes Duncan’s dissatisfaction with higher education systems in more personal terms. In it, he narrates the moment during his sophomore year at Berkeley when he realized that a traditional course of study was prohibiting his actualization as an artist:

In the early spring of 1938 I started working on a poem for a writing course which I was taking at the university at that time. As I wrote I found myself moving on and on in my mind through the nightworld of San Francisco, the movies, the creations of Stein, Dali, Joyce, Hart Crane; and I found that I was trying to make a pattern out of all of this that I had experienced and that, although I had been writing verse since I was in high school as a sophomore, there was something now to be communicated and I was not prepared to do this.

Comparing himself to a moth moving toward or away from a light, Duncan goes on to describe his excitement with finding new ways to make patterns with words and to communicate in writing. What he found, however, was that the university was not “in line” with such pursuits, concerned more with preservation than creation. He lamented that literature courses were more like “labs” for “craftsmen” or “museum courses” for “curators.” While he did not entirely object to such approaches, he needed something else:

By my conditioning when I approach Milton or Donne I am more the curator, the collector of culture than the reader. I enjoy the privilege of the curator attitude in reading; I feel that it is an added thrill. I NEED something else tho, time to work at writing, and I want to find a College where I can do that without the weight of guilt which hangs over the head when one must ROB Geology or English or French for a little time of writing.

The letter goes on to describe the projects he was engaged in at the time: a series of “moral and social” cantos titled “The Protestants”; a “psychological ritual” called “Hamlet” based on the themes of Shakespeare’s play; and another long piece titled “The Arctics.”[14] He included samples from all of these projects in his application packet, along with an excerpt from a piece called “The Carnivals” and a September 1939 issue of “The Phoenix.” Together, these writings anticipate Duncan’s later interests in serial forms and in the intersections between poetry and theatre — aspects of his work that would enrich BMC in its final years. They are also in keeping with the deeply political themes of Duncan’s early poems, especially the ways that these poems drew from early modern literary sources to establish critiques of the “capitalist ethic” and state power.[15]

Figures 3 & 4. Letter from Robert Duncan to Black Mountain College, September 29, 1939. Image courtesy of State of North Carolina Western Regional Archives.

Duncan’s application materials suggest similarities between his developing views of higher education and some of the principles that governed Black Mountain during the 1930s. Such principles, based largely on the application of John Dewey’s educational philosophy, centered the arts and emphasized experiential learning. Even Duncan’s stated desire to add “productive physical activity” to “intellectual work,” coupled with his experience gardening at a California mountain hotel (another qualification he noted in his application), demonstrated that he could contribute to the College’s required work program.[16] Duncan’s letters of recommendation confirmed that he was well suited to the experimental college. A letter from his Berkeley comrade, the painter and poet Virginia Admiral, described him as a “perfect fit” for the school. Another recommender, Ned Fahs, Duncan’s lover and a professor of Romance languages, relayed that “Black Mountain College will be as happy to admit Robert Symmes as he is to find a school like Black Mountain College.” Both letters also remarked that he was often called a “genius,” and that he accepted the compliment with grace. Additional letters of support came from Edward O. Baumann, an instructor of History at Reed College, and Edna Keough, Duncan’s high school English teacher.

The fact of Duncan’s rejection does not suggest that he wasn’t ready for Black Mountain — but, rather, that it wasn’t ready for him. In keeping with the College’s support of students devising their own courses of study, Duncan had already outlined a plan to follow should he be admitted. It was to include: “a correlation of twentieth century political, social, and aesthetic philosophies, accenting the expressionist tradition in visual and plastic arts and in writing and the position of the artist in society”; “a program of development of craftsmanship in poetry” that would include study of French translation, Chaucer, early modern drama, mystic poets, the Bible, and “expressionist developments in twentieth century prose and poetry”; and “craftwork in other arts than writing for relaxation.”[17] As Duncan himself wrote to the Black Mountain College faculty, it is nothing short of “some sort of crime for a twenty year old to have an idea of what he NEEDs” and not, in the end, be given the chance to pursue it.

Rejection

In Duncan’s recollection, he was admitted to Black Mountain College but then turned away after the campus interview. Both Duncan’s retrospective typescript and Ekbert Faas’s Young Robert Duncan assume that the primary reason was a “heated argument” about the Spanish Civil War. “In my anarchist convictions,” Duncan recalled, “the Madrid government seemed to me much the enemy as Franco was.”[18] Faas explains that, while Duncan was on campus, a debate broke out between BMC faculty and a young anarchist couple visiting from Mexico. Duncan emerged as the “lone defender” of the anarchist visitors and so “was turned away the following day.”[19] Certainly, late 1930s Black Mountain was dominated by staunch liberals. Duncan’s stated interest in his application materials in “marxian socialism” as well as his passionate declaration that his poems must address the “catastrophe that’s upon us” were, arguments about the Spanish Civil War notwithstanding, out-of-step with Rice and other influential faculty’s adherence to centrist democratic principles and their aversions to anarchism and communism.

In his later recollection, Duncan also wondered if, “back of that term ‘unfit’” was that “they had recognized that I was homosexual?” When Duncan returned to Black Mountain in 1956 with his partner Jess Collins, their openly gay partnership was, Lisa Jarnot notes, a “source of wonder” for young queer BMC students.[20] In its later years, Black Mountain College was an important site for the making of queer forms through the innovations of artists such as Merce Cunningham, John Cage, Ray Johnson, Jonathan Williams, and Duncan himself, among others. But, as Kyle Canter notes in his study of BMC photography and queer self-expression: “Queerness could exist at Black Mountain, but it had to remain contained.”[21] This was especially true during the late thirties. Early BMC faculty members Wunsch and John Evarts were queer, but it is unknown whether other college faculty knew at the time. In a retrospective interview, a former student, speaking anonymously, remembers that he was reprimanded by Rice for unintentionally outing himself.[22]

Duncan never really knew why he was rejected from Black Mountain in 1939 — and neither will we. Duncan’s rejection letter only relays that the decision of the Admissions Committee was “negative,” and that the news was “quite hard to convey” to someone with such a strong interest in the College. Upon receiving the rejection, Duncan wrote to Anne Mangold asking for help locating his lost luggage and requesting “to know the things which influenced the College in its decision” so that he might “recognize those things and by such a recognition to be better able to evaluate myself.” Mangold replied with a pat explanation: “[I]t is quite difficult to give an answer,” she wrote. “This is because the decision is reached not through a process of adding and subtracting clearly defined merits and demerits, credit hours, and the like, but through the personal judgment of a group of people on the basis of non-mechanical standards of academic ability and emotional stability and maturity.”[23]

While researching at the Western Regional Archives, I scoured faculty files, which included meeting minutes and faculty’s personal notes on admissions decisions, hoping that I might be able to piece together the story of Duncan’s rejection myself. I found only one document that lists “Symmes, Robert” among a handful of other students who would not be admitted to BMC for the 1939–1940 academic year. (Notably, the same document lists the painter Robert DeNiro, Sr.’s, application as “pending”; DeNiro, Sr., would enroll in the College in 1939.) In my failed attempts to figure out why a twenty-year-old Duncan was swiftly dismissed upon his arrival to Black Mountain College, I’ve found other reasons students were rejected during the college’s first years of operation. These included: financial reasons, poor grades, appearing apathetic, or because they seemed “mentally unstable.” In some cases, the board of directors feared admitting too many Jewish students at a time when the College was under scrutiny by the surrounding community for employing European war refugees. And these are only the reasons that survive in faculty meeting minutes or old notebooks. They occlude whatever “personal judgments” based on “non-mechanical standards of academic ability and emotional stability and maturity” that might have gone said but unrecorded.

Though I found nothing specific to Duncan’s case, my perusal of faculty notes suggests that the BMC admissions committee often made judgments about the “mental stability” of applicants. Such judgments, as Duberman points out, are in many ways a product of eschewing “itemized rules of conduct or traditional measurements of academic performance.” Because faculty “judged students by a wider criteria,” both in admissions and in division exam evaluations, negative judgments tended to be personal. “To be disapproved at Black Mountain,” Duberman observes, “… was the equivalent of being labeled an unworthy human being — not merely a poor student.”[24]

The early Black Mountain faculty, however, sometimes treated the College as a place where a supposedly lazy or undisciplined student could learn to be a productive member of a democratic community. (Given Black Mountain’s perennial financial woes, the admissions committee tended to take greater risks on students who could pay full price.) To give one example: Leslie Katz, the eventual founder of Eakins Press, was accepted to BMC in the fall of 1936 even though he was routinely referred to as “lazy,” “average,” and “undisciplined.” Katz was apparently admitted because Black Mountain’s educational approach would allow his to reach his potential. While a student, writing faculty such as Fred Mangold complained that he “stirs all kinds of mystical rabbits behind every bush” and “uses words as some people do dope.” One semester, Wunsch restricted Katz to a small area of the stage during theater courses just for the purpose of teaching self-discipline.[25] Many of the faculty responses to student work suggest that the young Duncan, despite his insistence that he belonged at Black Mountain, exceeded its institutional realities. I can’t help but wonder if at least a small part of his rejection was the committee’s realization that he would not be restricted or molded.

In a recent essay on the “archives of rejection,” Joshua Kotin examines rejected literary manuscripts to argue that “attention to small, practical decisions can illuminate large, abstract processes.”[26] The rejection of Duncan’s application reveals a false equivalency between the liberal educational ideals that underwrote that founding of Black Mountain in 1933 and the consolidation of Black Mountain poetry communities in the 1950s that would form the basis for the Black Mountain grouping in Allen’s anthology. During the 1930s, visual arts and music predominated the College, and the early writing curriculum was conservative. As Mary Emma Harris points out, an early BMC course catalog described writing as “one of the severest of disciplines.”[27] Instructors such as Mangold and Wunsch favored writing that was realistic and direct. Wunsch, one of the primary leaders of the creative writing and theater communities during the thirties, came from a North Carolina-based tradition that valued national folk traditions. His writing pedagogy, as Lucy Burns has shown, “was informed by a complex combination of progressivism, the models of craftmanship and professional writing employed in the creative writing manuals of the early twentieth-century, and the language of authentic personhood deployed as part of the college’s experimental practice of ‘group influence.’”[28] Wunsch favored, for example, the neat lines and quotidian imagery of student writers such as Jane Mayhall, who was admitted to Black Mountain in 1937 and would go on to enjoy a career as a poet later in her life. Like Duncan, Mayhall was desperately in love with the idea of going to Black Mountain. “Please understand,” she wrote Wunsch in a 1936 letter, “I want to come to B.M.C. because I think it will help me be a writer — But I am also wanting to come because I want to learn how to live.”[29]

I highlight these dissonances not to re-entrench established divides — between pre- and post-Olson Black Mountain, or between so-called traditional and experimental writing — but rather to call attention to the institutional dynamics that condition artistic production across such divides. Duncan’s return to Black Mountain was an “emotional victory” (to borrow a phrase from Jarnot) that might illuminate stark differences between 1930s and 1950s Black Mountain. But what might such a narrative also obscure? What if, instead of reading Duncan’s 1939 rejection as simply the specter of a later break or shift, we also understand it as a way to think through structural continuities? What literary scholars have come to understand as the “Black Mountain School” of poetry has long been dislocated from the operations of Black Mountain College as well as its location in Appalachia. Indeed, many Black Mountain poets never set foot on the Black Mountain campus. Duncan’s rejection is a constant reminder that, while Black Mountain College generated ideals of individual and community, it was also very much a school — one that tried to live out experimental principles while negotiating questions about admissions, budgets, hiring, and salaries; and that relied on fundraising and foundation money and dealt with the compromises such dependency brings.

While the poetry communities that formed at Black Mountain during the 1950s were certainly distinct from the early writing communities organized by figures such as Rice, Mangold, and Wunsch, the notion of a historical and institutional break elides the potential connections between the arts-centered progressive education models of Black Mountain’s early years, the experiments in collaborative interdisciplinary practice of the postwar period, and the becoming of what Mark Nowak calls the “American MFA industry.” Scholars such as Stephen Voyce have argued that “a sociological account of Black Mountain tells us a great deal about one of the most important accomplishments of midcentury poetry: the collaborative and interdisciplinary milieu of the college shaped Olson’s theory of what a poem should do.” Such a narrative, however, situates the literary output of the College squarely in its later years (1951 to 1956) and largely ignores the versions of poetry and of artistic community that preceded Olson’s arrival on campus and that took place at the margins of his sphere of influence.[30] In a way, this idealized version of community echoes Anne Mangold’s remark, from a document written in memory of her husband, Fred, that in its last years Black Mountain College “was not really a college.”[31] As I have argued elsewhere, to fully understand the consequences and potentials of Black Mountain’s short-lived experiment, it is necessary to understand that Black Mountain College was always a college.[32] Constructing a renewed sense of Black Mountain not as an alternative to university-based creative institutions, but from within what Jodi Melamed describes as the “paradox of institutionality,” it is possible to see in starker relief any potential alterities, collectivities, or radicalisms that existed before the college’s closing as well as in its variegated afterlives.[33]

“In writing, as in love, the acceptance might have more meaning,” Amitava Kumar writes, “but it is rejection that is close to the surface, always visible like a scar.”[34] What is perhaps visible on the surface of Duncan’s rejection is how institutions produce acceptable discourses about art and about how one is expected to behave in its social worlds. Among the many questions that remain, I can’t help but ask if Duncan only becomes recognizable to the College when his extraordinary genius becomes visible as something valuable that can be taken. The young Duncan’s rejection tugs at an often unspoken, sometimes dangerous, desire for institutional belonging, and it remains powerful in its provocation to think about the political and institutional realities that exist underneath — or paradoxically alongside — our dreams of going to school.

Notes

Thank you to Heather South for her expertise and unwavering support of Black Mountain College studies, to James Maynard for a generative correspondence that improved this essay, and to the State Archives of North Carolina and the Jess Collins Trust for permission to reproduce unpublished materials.

[1] An August 28, 1939, letter from Black Mountain faculty and then Secretary Frederick Mangold to Robert Duncan suggests that Duncan had written the College previously requesting application blanks and further information. Duncan’s application to the College dated August 30, 1939, indicates that he was not connected to anyone (students or faculty) at BMC and that he learned about the College from a Time magazine article. I assume the article Duncan references is “Education: Buncombe County’s Eden,” Time (19 June 1939).

[2] Frederick Mangold, Letter to Robert Symmes, August 29, 1939, Black Mountain College Records, North Carolina Western Regional Archives, Asheville, North Carolina.

[3] Robert Duncan, Letter to Anne Mangold, September 12, 1929, Black Mountain College Records, North Carolina Western Regional Archives, Asheville, North Carolina.

[4] Robert Duncan, Letter to Anne Mangold, n.d., Black Mountain College Records, North Carolina Western Regional Archives, Asheville, North Carolina.

[5] Lisa Jarnot describes Duncan’s New York City apartment in Robert Duncan: Ambassador from Venus (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2012), 58. Duncan’s rejection notice came in a letter from Anne Mangold dated September 30, 1939. Duncan and Mangold corresponded in early October about arranging to have his luggage sent to him in Annapolis, MD, care of Ned Fahs.

[6] Robert Duncan and James Maynard, “Black Mountain College,” Appalachian Journal 45.1-2 (2017/2018). Jarnot recounts Duncan’s rejection in Chapter 9 of Robert Duncan: The Ambassador from Venus, drawing on sources such as the 1955 typescript and Duncan’s correspondence about the rejection.

[7] Robert Duncan and James Maynard, “Black Mountain College,” 268.

[8] Jonathan Creasy, “A Grammar of the Art of Living,” Black Mountain Poems (New York: New Directions, 2019).

[9] The file’s contents confirm, for example, that Duncan was not rejected for financial reasons. There is no indication, however, that Duncan was initially accepted to the College and then rejected after visiting campus, as he once contended.

[10] Robert Duncan student application to Black Mountain College, August 30, 1939, Black Mountain College Records, North Carolina Western Regional Archives, Asheville, North Carolina.

[11] The Collected Early Poems and Plays, Peter Quartermain, ed. (Berkely: University of California Press, 2019), 3.

[12] Robert Duncan, Letter to Anne Mangold, September 12, 1939, Black Mountain College Records, North Carolina Western Regional Archives, Asheville, North Carolina.

[13] Robert Duncan, Letter to Black Mountain College, n.d., Black Mountain College Records, North Carolina Western Regional Archives, Asheville, North Carolina.

[14] It is possible that the typescript of “The Arctics” included in Duncan’s student file is one of the few, if only, extant copies of this work.

[15] Duncan, Collected Early, 8.

[16] Robert Duncan student application to Black Mountain College, August 30, 1939, Black Mountain College Records, North Carolina Western Regional Archives, Asheville, North Carolina.

[17] Robert Duncan, Letter to Black Mountain College, n.d., Black Mountain College Records, North Carolina Western Regional Archives, Asheville, North Carolina.

[18] Robert Duncan and James Maynard, “Black Mountain College,” 268.

[19] Ekbert Faas, Young Robert Duncan: Portrait of the Poet as Homosexual in Society (Santa Barbara: Black Sparrow Press, 1983), 63.

[20] Robert Duncan: The Ambassador from Venus, 152.

[21] “Jonathan Williams: Photography and the Queer Self at Black Mountain College,” Journal of Black Mountain College Studies 14 (September 2023).

[22] Excerpts from the interview with “John Doe” are reproduced and discussed in Martin Duberman, Black Mountain: An Exploration in Community (Evanston: Northwestern University Press, 1972), 69-70.

[23] Anne Mangold, Letter to Robert Symmes, October 5, 1939, Black Mountain College Records, North Carolina Western Regional Archives, Asheville, North Carolina.

[24] Duberman, Black Mountain, 80. For an examination of Black Mountain College admissions and evaluative practices during the 1930s, see Chapter 4 of Duberman, Black Mountain.

[25] Faculty comments on Leslie Katz division exams, n.d., Black Mountain College Records, North Carolina Western Regional Archives, Asheville, North Carolina.

[26] Joshua Kotin, “Archives of Rejection,” American Literary History 36.1 (Spring 2024), 206.

[27] Mary Emma Harris, The Arts at Black Mountain College (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1987), 73.

[28] “‘Creative Writing […] has a place in the curriculum’: Robert Wunsch at Black Mountain College, 1933-43,” Journal of Black Mountain College Studies 11 (October 2020).

[29] Jane Mayhall, Student application to Black Mountain College, August 25, 1936, Black Mountain College Records, North Carolina Western Regional Archives, Asheville, North Carolina.

[30] Stephen Voyce, “Alternative Degrees: ‘Works in OPEN’ at Black Mountain College,” After the Program Era: The Past, Present, and Future of Creative Writing in the University, ed. Loren Glass (Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 2016), 86. Voyce does mention the marginalization of women writers in the Black Mountain School but does not go into detail. On Black Mountain and women’s poetry, see Rachel Blau DuPless, “Manhood and Its Poetic Projects,”Jacket 31 (October 2006), and Lynne Feeley, “Expressions of Something Shared: The Women of Black Mountain College,” The Nation, November 25, 2019.

[31] Anne Mangold, Untitled typescript, n.d., Box 1502.2, Mr. and Mrs. Frederick Rogers Mangold Papers, North Carolina Western Regional Archives, Asheville, North Carolina.

[32] Sarah Ehlers, “A Plan for Black Mountain College,” Aydelotte Foundation, February 16, 2022.

[33] Jodi Melamed, “Proceduralism, Predisposing, Poesis: Forms of Institutionality, In the Making,” Lateral 5.1 (2016).

[34] Amitava Kumar, Every Day I Write the Book: Notes on Style (Durham: Duke University Press, 2020), 188.