On Bill Berkson and Frank O'Hara, 'Hymns of St. Bridget'

Deep fun

Hymns Of St. Bridget begins simply enough in October 1960 as the first collaboration between Bill Berkson and Frank O’Hara — from there it multiplies energetically into an ongoing exchange between Berkson and O’Hara that includes the FYI poems, The Letters of Angelicus and Fidelio, and Marcia: An Unfinished Novel. The synergistic impact of this poetic alliance extends beyond the literal collaborations and can be seen, for example, in the many poems by O’Hara referencing Berkson between 1960–1962: “For the Chinese New Year & for Bill Berkson,” “Bill's Burnoose,” “Biotherm (for Bill Berkson),” and others. Beyond “Biotherm” — a long poem that begins as a sort of pseudo-meditation on a skin cream — O’Hara further engages the chatty style explored in Hymns through a series of dialogues with television shows and films. “The Jade Madonna” (1964) has, for instance, the ambiance of the poet in collaboration with an old western movie:

I’ll give him two more days

and if he don’t think of

a way to get Wyatt Earp out of here by then

I’m going to

plant some corpses.

And then:

I got $820. $820? Yeah dollars. I kind of like having property.

Possession is better than

a ranch. That’s why I collect

all these things that have nothing to do

with cows

with dollars or with the great open range.

Smell that?

that’s my cows thinking about my money. [1]

“Fantasy” — dedicated to the health of Allen Ginsberg and wrapped around scenes from the 1943 World War II film Northern Pursuit — is also O’Hara in high filmic/conversational mode:

The main thing is to tell a story.

It is almost

very important. Imagine

throwing away the avalanche

so early in the movie. I am the only spy left

in Canada,

but just because I’m alone in the snow

doesn’t necessarily mean I’m a Nazi.

Let’s see,

two aspirins a vitamin C tablet and some baking soda

should do the trick, that’s practically an

Alka

Seltzer. Allen come out of the bathroom

and take it [ ...

... ] Allen,

are you feeling any better? Yes, I’m crazy about

Helmut Dantine

but I’m glad that Canada will remain

free. Just free, that’s all, never argue with the movies. [2]

Lytle Shaw, in his essay “Gesture in 1960,” provides yet another portrait of O’Hara composing through the ludic play of conversation in his discussion of O’Hara’s collaboration with the painter Norman Bluhm, Poem-Paintings. Bluhm emphasizes the “spontaneous and intersocial aspects of working on all the tacked up Poem-Paintings at once” while hanging out in the studio and listening to music. [3] As with the Berkson/O’Hara collaborations, Bluhm characterizes his collaboration with O’Hara as “instantaneous, like a conversation between friends.” [4] In an interview Bluhm notes that all the pieces in the collaboration “came out of some hilarious relationship with people we knew, out of a particular situation.” [5] Does the analogy of gesture — as used in painting — work when applied to writing? Can it apply to the role of conversation in the work? Berkson, in a recent interview, explains the intersection of conversation, gesture, and writing when he describes gesture as linking the space of a poem and the breath, perhaps like Olson or Kyger or Ginsberg. And he points to the physical presence of the line as a poem is composed, “the line moving through space-time.” [6]

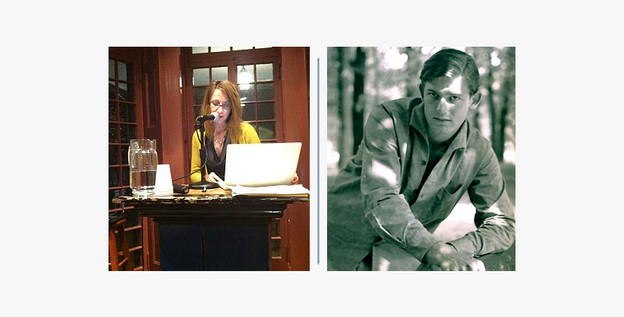

“What is the role of humor?” I asked Bill Berkson over the phone. The way he paused, it sounded like maybe he thought it was a bad question. “The role ... of humor ...,” he said slowly, “is ... to have ... fun.” He repeated it with no hesitation. “The role of humor is to have fun. To keep things rolling. It’s the only way to do collaboration. To roll it. Most of it is having fun — fun between friends.” Berkson notes that “in the collaborations there is a sense of having fun, of humor — that is the way to do it [...] Allen Ginsberg talked about deep gossip — so why not deep humor? I’m sure there are deep, lyric moments in the collaboration. But one can also have deep humor.”

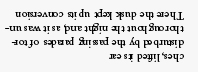

The story of how the collaboration Hymns Of St. Bridget got rolling can be found in the notes of the Owl Press publication of the book. [7] Berkson and O’Hara were walking along First Avenue and noticed the crooked steeple on a church — which I imagine was likened to a limp phallus — and they laughed about it. Berkson went home, still thinking about the limp steeple of St. Bridget’s church, and wrote “Hymn To St. Bridget’s Steeple” in what Berkson calls “a sort of poor imitation of O’Hara.” [8] “It is to you, bending limp and ridiculous, on Ninth / Street, that I turn” begins the first poem of Hymns Of St. Bridget, a conversational-rhetorical direct address Berkson considers his imitation of the high O’Hara or Ginsberg mode. “I showed it to Frank and he said, ‘Why don’t we do a series of these?’”

When Berkson came to Frank O’Hara with the poem he had just written, “Hymn To St. Bridget’s Steeple,” it had not occurred to him to make the work into a collaboration. The young Berkson had done just one collaboration, with Kenward Elmslie, which was later published in the Summer 1961 collaboration issue of Locus Solus edited by Kenneth Koch. Hymns proceeded, at O’Hara’s urging, with the next poem in the series, “St. Bridget’s Neighborhood”:

St. Bridget I wish you would wake up and tend my bumper

It’s cracked it is like the thought

I had of you when I cut myself shaving “O steeple

why don’t you help me as you helped the Missouri islanders?” [9]

The two poets — O’Hara in his mid-thirties and Berkson in his twenties — wrote Hymns my-turn-your-turn style at a single typewriter:

The

afternoon is leaning toward drinks I am getting

myself one now though I shouldn’t Would

you like one, heaviness of the compost thresh-

hold? No, I want the plants to have it, for

they have died [10]

At this point in the story I should offer an explanation about the subject of Hymns Of St. Bridget in the context of a symposium of books published in 1960 — for Hymns was not published until 1974 by Adventures in Poetry. In fact, only two of the poems from the collaboration were ever published during O’Hara’s lifetime, in the May/June 1962 issue of Evergreen Review (“Hymn To St. Bridget’s Steeple” and “Us Looking Up To St. Bridget"). 1960 was, however, the beginning of this significant poetic dialog between Berkson and O’Hara. Hymns Of St. Bridget launched a flurry of collaboration, beginning aptly with the two poets walking along First Avenue and laughing.

By 1960 O’Hara had well established his “I Do This and I Do That” style and so came to the collaboration with these gestures in hand — and Berkson notes that he was heavily influenced by O’Hara’s work at that time. Berkson himself was increasingly working with open field pieces, as evidenced by poems dating from 1959 to 1961 and published in All You Want (1966):

my hat

your. . . the crumplings of an evening

put forward as ice was

ah trolley!

the except

our still-life yearings allow tunes

to the far suburbs [11]

If ludic play is significant throughout the collaborations between O’Hara and Berkson, then it is perhaps also an important contributor to the so-called “third voice” of collaboration as well. O’Hara’s work increasingly moves from painterly to filmic and the collaborations become increasingly untamed and open as they accumulate. “I think Frank was very excited by this,” says Berkson, “and on his own he began to write things that were wilder and wilder, leading up to “‘Biotherm.’”

troika And back at the organ the angel was able to play a great

singe green tree for the opening of the new bank

Caracallo it was

the loin the last opening of a bank anywhere because the angel’s wings

sloth got clipped in the swimming pool

it ate well and had glorious nightmares days

she hated it

“Satan, hélas? c’est vous?” April had rushed into May while

she was reading Hollywood Babylon

and now the trees wore evil fringes where buzzards roosted

covered with old prayer beads

An awning flapped. [12]

[1] Frank O’Hara, The Collected Poems of Frank O’Hara, ed. Don Allen (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1979), 484–85.

[2] Ibid., 488.

[3] Lytle Shaw, “Gesture in 1960: Toward Literal Solutions,” in Frank O’Hara Now, ed. Robert Hampton and Will Montgomery (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2010), 40.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid., 38.

[6] Bill Berkson, interview by Mel Nichols, November 27, 2010.

[7] Bill Berkson and Frank O’Hara, Hymns of St. Bridget & Other Writings (Woodacre, CA: Owl Press, 2001), 83.

[8] Bill Berkson, interview by Mel Nichols, November 27, 2010.

[9] Bill Berkson and Frank O’Hara, Hymns of St. Bridget (New York: Adventures in Poetry, 1974), 15.

[10] Ibid., 14.

[11] Bill Berkson, Portrait and Dream: New and Selected Poems (Minneapolis: Coffee House Press, 2009), 47.

[12] Bill Berkson and Frank O’Hara, “St. Bridget’s Hymn to Philip Guston,” in Hymns of St. Bridget, (New York: Adventures in Poetry, 1974), 29–30.

Edited by Al Filreis