Lyn in landscape

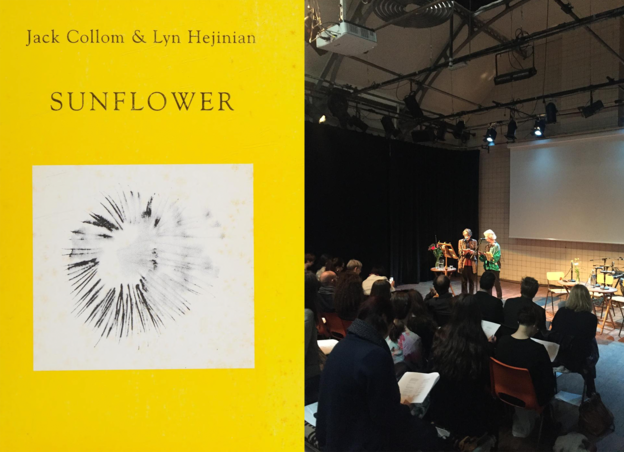

Lyn isn’t usually read as a writer of landscape or region, even though her work came into being mainly within a focalized, and beloved, locality. When I first moved there, I had trouble integrating place and time. Sometimes I mistook the bewilderingness induced by plum blossoms in February for a more sentimental disorientation and would end up in professors’ offices with no good questions, just a feeling that needed to land. The first time I showed up in Lyn’s, she gave me The Sunflower, a collaboration with Jack Collom. Somehow she knew flowers would become a central entry point of inquiry for me.

What struck me most about that chapbook, however, was the biography at the back. Author bios are one of those sub-sub-genres, like dedications or endnotes, where readers expect authenticity, unmediated access to the real. In My Life and elsewhere Lyn reconfigured the way a life could be written — as edge effect and ecotone, rather than central path. So it makes sense to me that she would play here, too. She gives outsized space to her teenage years in “New England,” specifically “the unkempt Wayland (Mass.) Cemetry (sic),” and its “gravestone poetry,” her “hideout in the woods at the edge of the Sudbury River marshlands,” eventually “discovered and dismantled by local police.”[1]

This vision of Lyn as a teenager in eastern graveyards and marshes, evading the authorities, delighted me. Humor is such a defining, and inviting, register in her work. But it also felt familiar. What I’m only now beginning to understand is just how much her articulation — and modeling — of the co-creativity of language and life informed the work I ended up pursuing at Berkeley and beyond. Because Lyn taught that language could be “open” regardless of form, I could see Herman Melville’s writing as charged at the peripheries, even at its most seemingly structurally rigid, how longing infiltrated the way he wrote moss. Because she had identified poetry as not a “genre” but an “inquiry,” I could understand Henry David Thoreau as primarily a poet, regardless of his copious prose.[2] And, at the same time, Lyn offered a further permission, one that has become increasingly important as I move further from scholarship into writing. “My life has been the poem I would have writ, / But I could not both live and utter it,” Thoreau somehow got onto paper.[3] But Lyn showed that living and writing were in full collaboration, happily, daily.

She also offered a relation to place defined by time, rather than the tedious descriptiveness of much so-called “nature writing.”[4] Treated as space, landscape becomes heavy with nouns. Whereas place as time can be sequenced — lighter, more flexible, with opportunities for synchronicity, parataxis, lateral leaps. And while a hill is a hill is a hill, any story, like the vector of a sentence, can be diagrammed multiply, bend, or even break.

The year I left the Bay, one of Lyn’s advisees, Samia Rahimtoola, read a passage from The Book of a Thousand Eyes as the officiant at my wedding: “The marriage is not, in fact, the true beginning. First the sun came up. The night before that it rained, but the storm passed and by dawn the leaves on the trees in the park appeared to be juggling beads of gold light in the breeze . . .”[5] We were standing between two oaks. There was a marsh I wanted invited as a guest. A ritual acknowledging everything, especially love and commitment, as intersected by location.

When I read this passage now, I see how a day moves over a landscape’s face. How you can see the storms coming from a long way off. The ambience Lyn applied to life writing also defines her writing of place. One of her most radical offerings is the belief that emotions, moods, states of being, “happiness,” “joy,” exist [...] without us,” “bound to [their] own incompleteness sharply.”[6] Environmentally. So, the pickerel sprouting by the muddy banks of the Sudbury was a happiness connected to Thoreau, to the child in my arms, and Lyn, as camping adolescent, brilliant teacher. And whatever was dancing around the lupines by the sideroad, the slime mold by the creek this morning, in Santa Barbara, all that Lyn composed around her, the feeling of it, was in that edginess, also, was the feeling of that edge.

Notes

[1] Hejinian, The Sunflower, unpaginated.

[2] Hejinian, “The Rejection of Closure” and “Introduction” in The Language of Inquiry, 43, 3.

[3] Thoreau, A Week on the Concord and Merrimack, 343.

[4] Hejinian, “Landscape & Grammar,” in The Language of Inquiry, 112.

[5] Hejinina, The Book of a Thousand Eyes, page.

[6] Hejinian, Happily, 8, 24.

Edited byMargaret Ronda Jennifer Scappettone Mia You Julie Carr