The blues, Tom Weatherly, and the American canon

In 1964, as I was about to leave for college, I attended James Baldwin’s new play Blues for Mr. Charlie. By then, Everett LeRoi Jones (a.k.a. LeRoi Jones, subsequently Amiri Baraka) had moved to Greenwich Village, though I would not discover him till the following year. Jones’s equally brilliant and even more searing play, Dutchman, was also first produced that year. Baldwin had published Notes of a Native Son in 1955, which helped to create a Harlem of nearly mythic stature as he delved into its sorrows, complexities, and triumphs. Nobody Knows My Name (his title essay first appearing in 1959) was published three years before his play. The two books would find me much later in life. Not so Preface to a Twenty Volume Suicide Note, LeRoi Jones’s first poetry collection, which also appeared three years before Blues for Mr. Charlie and Dutchman. The poems in that book seized me and would not let me go in the mid-sixties — which was when I met Tom Weatherly.

If you read Weatherly’s sixties and early seventies poetry in something more than a cursory way, you’ll see Preface in them. Jones’s book seized him too — although I won’t say that it was seminal for him. Preface to a Twenty Volume Suicide Note, Dutchman, and Blues People (appearing in 1960) were written by someone hailing from Newark, New Jersey, who had made a life in Greenwich Village. Notes of a Native Son, The Fire Next Time (1963), Blues for Mr. Charlie, and Nobody Knows My Name, which contained the great essay “Nobody Knows My Name: A Letter from the South,”were written by someone born and raised in New York City. I wonder now if all these canonical works, already being seen by some in the sixties as just that, constituted a basic premise Weatherly — who was born and raised, and who died, in Alabama, after living most of his adult life in New York — would transform into his own overwhelmingly powerful and beautiful language, style, and point of view. What did he bring to the discussion, not only in New York, which neither Baldwin nor Jones (who becomes Amiri Baraka) could? The terribly moving and profoundly insightful “Nobody Knows My Name” was the observations of someone, Baldwin, who was seeing something for the first time, having just discovered the South. This great achievement of investigative journalism was a profoundly poetical meditation on just that:

It was on the outskirts of Atlanta that I first felt how the Southern landscape — the trees, the silence, the liquid heat, and the fact that one always seems to be traveling great distances — seems designed for violence, seems, almost, to demand it. What passions cannot be unleashed on a dark road in a Southern night! Everything seems so sensual, so languid, and so private. Desire can be acted out here; over this fence, behind that tree, in the darkness, there; and no one will see, no one will ever know. Only the night is watching and the night was made for desire. […] In the Southern night everything seems possible, the most private, unspeakable longings; but then arrives the Southern day, as hard and brazen as the night was soft and dark. It brings what was done in the dark to light.

What Baldwin discloses to his northern readership (he was on assignment from Partisan Review) was the very hot, languid air Weatherly breathed from his first day on earth.

I first met Tom Weatherly (a.k.a. Thomas Elias Weatherly Jr., a.k.a. Elias Weatherly, a.k.a. Weatherly, a.k.a. eliyahu ben Avraham in later life after he converted to and devoutly practiced orthodox Judaism) in 1966–67, when both he and I were setting ourselves down in the Village (East and West) to be poets in some serious way. I tried to emulate the then-Jones (as well as other poets mostly of what were considered to be the Black Mountain School, such as Joel Oppenheimer). In Weatherly’s 1970 collection of poems, Maumau American Cantos, references to — and otherwise the calling out of — Jones abound. I didn’t know it then like I know it now, but Weatherly’s arrival in downtown Manhattan was momentous in ways mostly forgotten. It’s time to remember.

Weatherly marks his arrival with a poem he names “a proper song, entitled: coonbitch, to polly green”:

traveln salesmen pump my joint

collective farm wife, make this

killn floor stern, killn deck

aft document:

roi jones

in the year of our lady

did you not write

on page 17

“old envious blues feeling”

the hound diggings where

ole bean dug up a pewter raccoon

our roots too deep to go down

or own to bunny

who’ll buy my violets

i can’t get started.

the peckers ride off

lookout mountain to some pass.

cut them off at possibly

possibly mosby is the posse

the marshal clan &

chases the treed muse, the flower of

backdoor.[1]

Get outta town, Roi!

By the time Weatherly came on the scene, Jones had already married Hettie Cohen, and they had had children together. Here’s Weatherly’s poem “roi rogers and the warlocks of space” (the third in a “roi rogers” series):

hadassah leavenburg

baby you’re selected

marry me in my pre

fascist period. Why

because i

dig yo fat

thighs

rumped ass

bald domed tits

cunt that’s a live

home to huge beasts.

we be fuckn kosher

‘til I find what

shine means.[2]

Weatherly also married a Jewish woman, Carolyn Samuels, and they had a son, Thomas Weatherly III (“Lil’ Tomcat,” back when). Here’s a poem, “east corinthian” (the eleventh and final canto in his 1970 volume), telling some of that story:

village period piece hettie

cohen got her jones, wiped th colostrum

off th mouf of his first poems

days down wif it.

east fifth street kikes have retreated to

maw of long-guyland, few ulanower cong.

a saturday holdn act from soap opera kahn.

lissen mama right-handed-wingd

i’m head tomcat round this spray

net weight in th morning

c-wt. & eighty th motherfuckn all

limitd to th east side & fillmore music

gem spa & i cant spare a dime.

my poems & lil tomcat in your belly

teethn on raw blood too are down wif it

(totem is in th spirit house) th red-

bone hunger.[3]

Looking back on Weatherly’s life and work, I don’t think it’s a stretch to say that they inhabited the Blues, filled in the Blues like a filled-in sketch now in color and depth, helping the Blues to attain its full, great stature for which it was destined. That it took a writer or two to make this happen, musicians aside, is to me a curious fact.

I will have more to say about his poetry shortly, in the above regard, but here it’s important to mention the groundbreaking anthology he coedited in 1970, Natural Process: An Anthology of New Black Poetry (in which — he insisted upon it, me a white Jew — I was published under the pseudonym L. V. Mack, the maiden name of a young woman who would become my first wife). To say that Weatherly and his work were idiosyncratic — or, to use a favorite word of his in his poems, eclectic — would be to state the obvious. In any case, he was a downtown guy — a mainstay at the Poetry Project, a participant in the Umbra Collective, who worked in Village restaurants and bars. But at that time how could he not have felt the magnetic force of uptown Manhattan? Although a participant (along with the likes of Edward Albee and others who would later be highly celebrated) in the Playwrights Horizon workshop in the West Village (whence in 1964 Dutchman was written in a single drunken night after a workshop session),[4] Baraka, Weatherly’s senior, left Hettie and their kids along with his literary name, LeRoi Jones, to found the Black Arts Movement uptown (later returning to Newark, New Jersey, where he lived out the rest of his life with his wife Amina Baraka, formerly Sylvia Robinson, and their children). To understand Weatherly’s poetry one has to consider the two poles he was pulled by once he arrived in New York from the deep South. Baldwin was of course an uptown figure, and at that time the éminence grise.

I thought Weatherly’s writing in the late sixties was groundbreaking and had a lot to teach me as a fledgling poet. My fellow student at SUNY Cortland, Michael (M. G.) Stephens, had left school and set himself up in the East Village (as would another of us, Ron Edson, also a Cortland alum); having visited them and gotten a taste of what was happening there, the poetry especially, I myself left college at the end of 1967. Mike, Tom, and Ron were all members of the inaugural creative writing workshops at the Poetry Project, which was begun by Paul Blackburn (who would come to Cortland College to join its faculty) and whose first director was Oppenheimer; I attended Joel’s workshop once, as well as readings at the Project at that time, and would see Joel and everyone else at the Lion’s Head (the famed West Village watering hole for writers, poets, and journalists), where Tom was employed.

In Cortland, we three students were part of another workshop, which had been created by David Toor, a professor. David’s brother worked in the same print shop as Joel. Many of the Black Mountain poets (and others who were included in Donald Allen’s game-changing anthology, The New American Poetry: 1945–1960) thus came to Cortland to read and participate in our workshop. Eventually Weatherly was also brought to Cortland to do the poet turn.

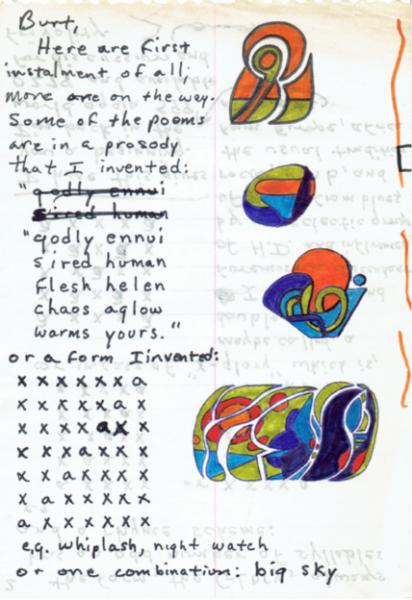

The Black Mountain school, as it had come to be called, its poetics, was rooted in the modernist poetry of what the scholar Burton Hatlen once called “The Philadelphia Three” — Ezra Pound, H.D. (Hilda Doolittle), and William Carlos Williams, who, all still in their teens, first met in and around the University of Pennsylvania (Marianne Moore was not far off, in Bryn Mawr). In a 1986 letter, you can see Weatherly’s debt to both H.D. and Pound. “I’m trying to go beyond my serious use of pun-like tropes to whole passages with that effect,” he writes, possibly indicating as a purpose to make a poem in its entirety that has the unitary force of some ur-word. “The human passions are such,” he says, turning to H.D and her poetry’s influence in his poetry:

I hope I’m successful in what I say is a development of H.D.’s way of imaging and playing, with the jazz, blues, r n b, and country phrasing (& fugal influences[)]. We have strayed to [sic] far from dance music and its humanity.[5]

Years later, in a letter, he writes:

Burt, I know that you have ideas where I belong in the poet poem [these two words are written one above the other] spectrum. I claim that, broad sense, I àm a descendant of the imagists and the bluesists, and, and et cetera. I belong to the school of eclecticism; I will use any method, mode, and technology ever used so call me an eclecticist if you wish to call me something other than poet, just poet — acolyte of the syllable. Yes, the syllable; the word, the semantic content is our personality[,] it moves automatically out of our nature and nurture. We must make our poems sound.[6]

In many ways Weatherly, and another eclectic poet, Ronald Johnson, are quite different. Yet their comparison is useful. They were both, let’s say, “eclectic.” And they both loved form and how words resided on the page; and they both shared the Pound-H.D.-Williams, and then Black Mountain, tradition. My feeling, perhaps an exception to a widely held view, is that Weatherly didn’t need to be eclectic but everything about him insisted on being exactly that, and what that was would never, could never, fit into anyone’s category or description. He was a person of a number of worlds that, on their face, would have nothing to do with Alabama where he grew up, returning to in old age, in the meanwhile living a life disparately. What pulled the threads of various worlds into a single skein was Weatherly the poet, and those who knew him, who read him, who were possibly excited and awed by him and loved him, were the larger for the grand poetic world he erected.

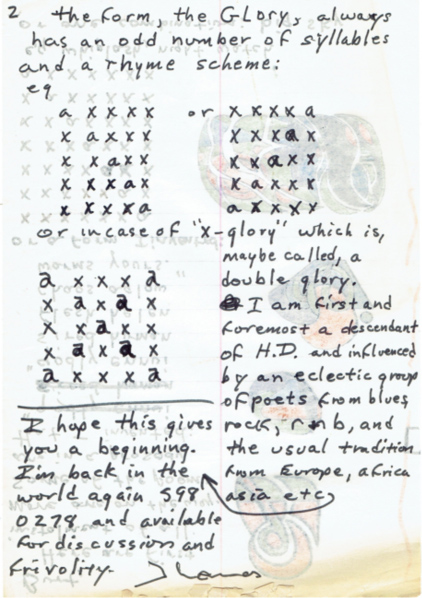

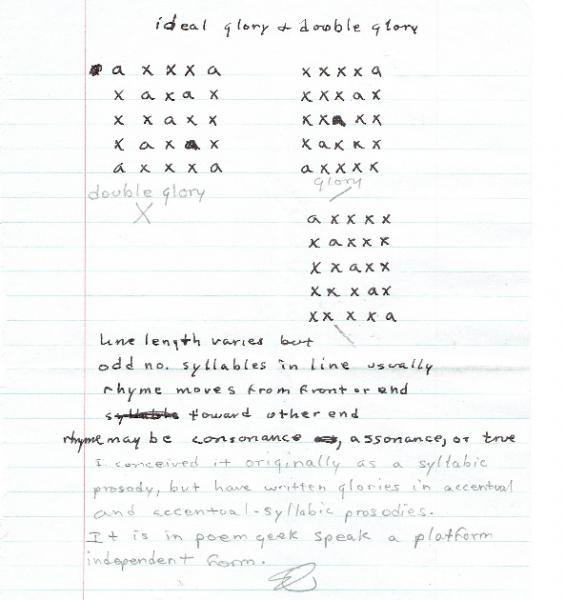

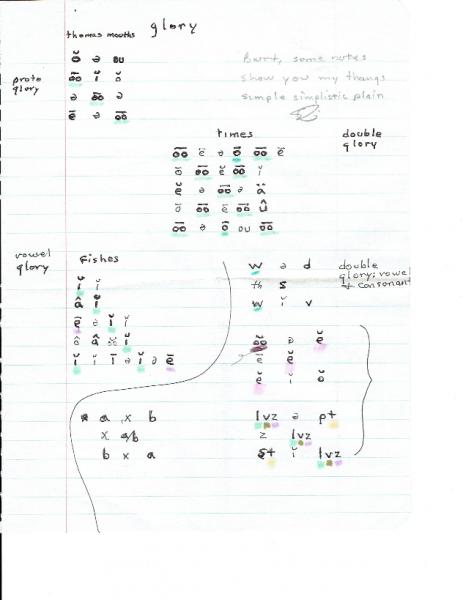

Some of what H.D. may have had to show him was how a word could sit on a page. He invented forms — the Glory and the Double Glory.

The above two images were part of a longer, now undated, letter — the envelope is missing — most likely sent to author in the mid- or late 1980s.

While the Glory and the Double Glory are entrenched in sound — as regards syllable stress, pitch, duration, rhyme, and so on (note, for example, in the diagrams above the crisscrossing of the rhyme sound in the Double Glory), I think the look of a Weatherly poem was a matter he also took seriously. (Is it easier to have clean visual lines when your poem has only three syllables on a line, let’s say, and only two or three lines in a stanza?) Here is more diagramming, with some of Weatherly’s explanation, of these forms (note the attention he pays to consonants and their relationships to vowels):

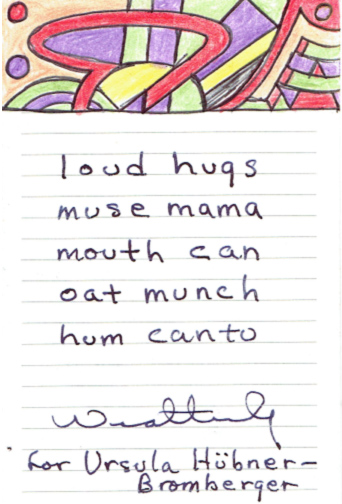

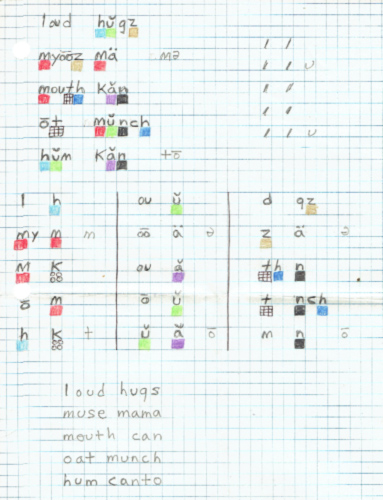

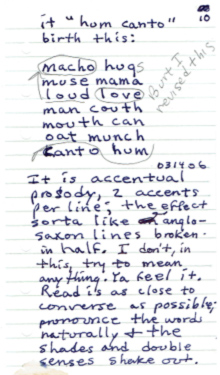

Looking at the below text, and the diagram following it, consider how many multisyllabic or Latinate words can be employed within the short line, and the short-poem form.

Now notice, in the below, how Weatherly works out the poem and explains it (n.b.: “canto” here comes from Pound’s The Cantos).

The above five images are contained within the previously cited letter to author, May 13, year uncertain due to blurred postmark.

Weatherly knew Pound’s work inside and out — yet it was H.D. who became not so much his muse as his interlocutor or confidante.

A cotton mouf uttered the most elegant language imaginable, was not averse to making reference to classical roots, and from them Weatherly’s coming into fullness as a poet (“thomas mouths / smooth mythos / medusa / seemed amused”[7]). He honored them in their bettering (“enter crete adept / erect word temple / poppy petal fumes / unset tunes never / better hd’s flesh”[8]). I found his poetry in the sixties and on through Mau Mau American Cantos, and Thumbprint published the following year, astonishing on a number of counts, among those his explorations well beyond the modernist purview.

What he was writing partook of a cutting-edge approach to understanding poetry that was present in the work of some other poets in those early Poetry Project workshops. Even so, his poems possessed a rigor and, let’s call it, deeply intuitive grasp of, and belief in, syntax vis-à-vis particles of speech, with which he fashioned a music that was more muscular than just being sinuous. His music — which in his mature work can be experienced vividly and deeply at the same time as it is being purposely strained through an austere prosody — never departed from its sonorous values, remarkably, at the same time that in it we feel the thud of talk, of human speech.

Weatherly’s poetry — erudite and adventurous — truly stands alone. At first the poetry will not disclose its erudition — not even, at first, its amazing wit and profound insights, yet, after reading some of his poems, and letting them settle in, the full magnitude and singularity of their lyric voice begins to make its presence known. Furthermore, we can find his mature lyric voice in the early poems (something I’ll turn to shortly), such as this love poem from the 1971 collection:

Nadine

for vlada

we hold hi school hands

fuck i mean that

as love we workd out

th 50s our own down ways

dreams would be jaild.

your jelly mama

th way you walk & roll ass

soul eyes innocent.

black cat bone hunger

pigmeat heifer. fuck you

like a song chuck

berry.[9]

In passing, let me note the fact that here we are seeing an American poetry (of course, “nadine” refers to the Chuck Berry song if not to something or someone else), for all its calling out of America’s murderous shortcomings — which can be addressed directly, or which, as in the above poem, can simply be an immanence out of which the lyricism springs. The darkness in the lyricism is ever-present, while the élan of a Weatherly poem establishes an unexpected beauty and grace. In Maumau Weatherly had written:

“South African Judge

Rules Family Is White, New York Times

Not Colored.” April 30, 1967, p. 86

court changen race by legal decree

worn it is a gesture

as skin, suit won in south

african court i’d be proud

declared white in new jersey

or Georgia. proud america

experience limitd

to these states

i’m in for traveln.

whereas the greek states

beautiful the gods the heroes

if a jigaboo dont spill milk

coming he spill it going.

there are like homer’s blues

themes. black humpd under

magnolia writn

life of the great black

wasp. state

oracles divine, witch docs

sprinkle bone dust

americus mojo

i stay here wearing thin

suitd for the climate.[10]

Postmodern Blue

That the early poems’ originality finally redounds to some greater art and ethos cannot remain hidden for very long. The remainder of this essay endeavors to elucidate a poetics that takes Weatherly’s biographical circumstances into account. The poetics has its roots, as has been discussed, but I just want also to advance the notion that this poetics is peculiarly personal relative to his personal history. Needless to say that such an assertion may obtain to just about any poet — nevertheless, given the sweep of American political and cultural history during Weatherly’s lifetime (in which he played a part), I would argue that my consideration of his life within a period that, in some respects, might be said to have been marked by extraordinarily dramatic change, enjoys a special purchase in our coming to appreciate his artistic power.

Weatherly knew the Objectivists’ poetry and theorizing enough to rival them while drawing upon the lessons he’d learned especially from Pound and H.D. whom he never stopped studying. His emerging lyric voice when we were young was new news for me. His continuous meditation on language and what makes poetry would evolve, perhaps in part from his intellectual pursuits, yet I suspect that his utter mastery of the short line and condensed lyric, as evinced in the late and great volume of poetry he titled short history of the saxophone (in which the voice has receded while its haunting presence is felt as the essential element of the poem), is what most of all should be remembered.

Let me add to this one other thought, which has to do with what might seem like a gulf between the early work — before Weatherly seemingly let go of the need to pursue publication (or whatever it was that led him to step away from the public adulation he was earning) — and the work of short history. I would like to advance a thesis in this regard, having to do with at least an unconsciously developing praxis on his part, one culminating in the final section of this late book. This thesis has to do with his economy. I find in his poetry, increasingly pronounced in the late poetry, more meaning than would be possible in a larger number of words. Also, if you read through the mature book, you see the same words over and over.

These words often appear in the early books — not with such frequency, nonetheless in key poetic moments. Take, for example, the word blues — with its open “oo” sound, as in boogie tune, a key phrase of his, as well as in often-used words in his poems such as music, loony, brute,etc. They show off the favored “note” in the Weatherly oeuvre. What does that sound represent or evoke in our primal experience of life and death, of exquisite pleasure or pain?

The opening poem of short history of the saxophone, titled “musick,” anticipates the multi-section fugue concluding the book, wally. Even so, musick reaches back to the early books, establishing the basis for the fugue. What might it mean to find, in Weatherly’s poetry, the most highly refined as well as original brute music? That the following poem opens short history is not without special significance.

musick

bluesy subtle bluest

thence beauty blooms

sunlit bluets center

whence brutal musics

humans vent as blues[11]

Wally calls back to what I think is the greatest conception in Maumau American Cantos, the most powerful, raw, and graceful poem in that book, and what I regard as its signature lyric, “blues for frank wooten”[12]:

blues for frank wooten

House of the Lifting of the Head

let me open mama your 3 corner box.

yes open mama your 3 corner box.

i have a black snake baby his tongues hot.

you shake round those curves baby dont quite make the grade.

you shake round those curves baby dont make the grade.

man come home tired dont want no lemonade.

we been blowing spit bubbles baby in each others mouf.

we been blowing spit bubbles baby in each others mouf.

burst all them bubbles mama norf cold like the souf.

let me be your woodpecker mama tom do like no pecker would.

let me be your woodpecker mama tom tom do like no pecker would.

open your front door baby black dark come home for good.[13]

What goes relatively understated in this poem is fleshed out in its book’s multisectioned eponymous poem, where blues repeatedly carries out its pivotal function (as shown below).

MAUMAU AMERICAN CANTOS

1

intersection

honking sirens approach at,

searchlights

honk out

FRANK

kill you dipshit fagot

motherfuckers.

& frank never know

how to outguess stupidity

the blood, the mean

woodenframe the coptic site

blues

the mans honking

dont come

at my door.

CANTO 2

the yellow brick road

for trane[14]

we trespass the blues

hanging outhouses in picture frames

a record heard

live performance

blow easily

forgotten phrase. we bleep

dont read music. listen

dont move dont you remember

saxophones never die.

titty toad down

remember, read scratchy

sheet music, croak

in the backyard.

CANTO 3 [excerpt]

[…] the sirens

honk at my hymns to malcolm […][15]

CANTO 4 [excerpt]

speak of my

self respect

for myself

no success, the score is

success, the ritual put down

all the blues gone west

mongers of the world unite!

CANTO 5

coon fire

the landscape was

musical cartoons.

tattoo the sound of

blood on my eardrums

taut, the tenses

i were wolfish to dance

dance the half romance

the language

& violence, music to

dance to

violate the progress:

rust at the muscle.

CANTO 6 [excerpt]

americus mojo

brown stone woman honkn outside,

my honeydew rider.

o deliver me my lady, tom

reconstructed tom, dont ride no more fronts for the lily

BLACKJACK PERSHING

THE HIGH KITE SUCK YOUR

BONES.

east fifth street sings TPF out my ears[16] the morning

you’re not here

[…]

CANTO 7

first thesis

for m.l.k., jr.

aim get your sights & its sound

in abstract or journal movements

to a peace settlement

old fancy western

dude shot my man

dead,

precious lord blow off

theres no willy in th blues theres no you.

CANTO 8 [excerpt]

valley stream carol[17]

[…]

freight trains gone in last round house. home

fret no music made, no drama, shiftless

out of head gear, disorient blues takes firm

control these days keep me cool enuf collect

my thots my fingers (your river hips flow away)

swim wif th current holdn breath.

east fifth street children dont fear broken glass

come rescue me losing touch system

reality, blue singn me wif his bad mouf.

them mushrooms th stink of pool doos pussy

biography of joseph smith on my desk

life & times change again look old

things pewter wif designs on ’em made in england

unicorn products limited go lovely

to th kick hills. my tongue is blue any form you wish

come bird fish worm sing swim

loosen th black belt.

CANTO 9

lucy belle[18]

d b a rider

ginger hips bred

you said

captain easy

go down on

river hips

new orleans

louisiana

where my mouf sings

a goat song

(th chorus line.)

CANTO 10 [excerpt]

wooten

[…]

devil lights up th day knowing

which hat to wear in his

green avenue stompers above franklin

going downtown, th robins

by Stuyvesant, nostrum,[19] utica avenue.

over wireless ‘robins nest’ slim harpos

blue thang. do your thang blue sea

cop the reefer ride away

[…]

Here, in full, is the eleventh, and final, canto now in its proper context:

CANTO 11 [excerpt]

east Corinthian

village period piece hettie

cohen got her jones, wiped th colostrum

off th mouf of his first poems

days down wif it.

east fifth street kikes have retreated to

maw of long-guyland, few ulanower cong.

a saturday holdn act from soap opera kahn.

lissen mama right-handed-wingd

i’m head tomcat round this spray

net weight in th morning

c-wt. & eighty th motherfuckn all

limitd to th east side & fillmore music

gem spa & i cant spare a dime.

my poems & lil tomcat in your belly

teethn on raw blood too are down wif it

(totem is in th spirit house) th red-

bone hunger.[20]

I find fascinating the contrast of Thumbprint to the 1970 collection (such as the above). The word blues does not appear even once in the subsequent book published only a year later. Yet “blue” does appear, once, in Thumbprint, in “speculum osiris” (“bladderwort. Blue / frog in th harbor street”), and there are cultural cognates in “nadine” (the Chuck Berry reference, “song”), “oba skorpios” (“dirty boogies in texas”), “for billie” (alluding to Billie Holiday and ending with, on a concluding line set off from the rest of the poem, “loony tune”), and “peanut butter fly” (“let me see you boogie / woogie”). Some of the poems in Thumbprint may very well have been at least in development contemporaneously with those in Maumau.[21]

Wally, a conclusion

Did Weatherly plan for short history to be his final book, a collection meant to complete a conversation he’d begun, having set that conversation going in the later sixties and then in 1970 with Maumau, which was the first comprehensive display of what I believe he knew full well was a new and important poetry? Aside from the discourse proper, there is in the work, as I’ve suggested, a remarkable compression (à la Pound’s coinage, condensare), which is especially striking in the final book, but which was there, to be appreciated, in the earlier work.[22]

The series wally ends short history with a grand jeté. It is in itself beautiful, and is a most accomplished fugue that, like the blues in its structure, operates with a determinedly limited lexis. Weatherly is using his own form, the glory, as a basic prosody; yet underlying that is an interchangeability of words within a construct of beat and dense sonority. Here’s the first of the poems in wally:

never muted heart

never muted heart

eclectic blues guitar[23]

The repetition, no doubt, is key.

Wally develops its proposition in intervals, which holds that “in death brute’s reward / an artful western music / [is] meant to true the heart” (88). This argument moves through its own set of permutations. Contrapuntally, the opening tercet evolves on a parallel path with this:

tulip petal larvae

tulip petal larvae

eclectic blues guitar (89)

The next poem, a counterpoint, begins with “never muted heart” and ties the two mini-series together in its following line, the closing phrase of the tercet’s three lines (the two mini-series merge briefly in the subsequent three-liner, where the third line becomes the premise, thus pushing the conversation of the poem forward):

eclectic blues guitar

eclectic blues guitar

never muted heart (90)

We have returned to the start of wally, while, however, our attention is fixed upon a sonic mirror, so to speak. The poem continues, from this convergence, into its culminating movement in which a repudiation, or at least a qualification, of the “western” influence, already declared, comes to the fore:

never muted heart

eclectic blues guitar

hardon belly groove

move your heady arse

hoodoo bard from heaven (92)

The child of highly educated parents (educated in the Western tradition), Tom Weatherly was the consummate connoisseur of a literary modernism steeped in Western ideas and aesthetics. He has shown his command of the Western lyric while taking that lyric as a vehicle to elevate the blues to the great stature it deserves. In doing so he makes clear its roots in slavery, America’s original sin, and American slavery’s legacy. To the slave-holding white class the illiterate, the brute, that brutish composer and singer, creates the American art form, blues then jazz, finally in all its exquisite complexity, subtlety, and grandeur.

Here is how wally ends, arguably prompting us to reread Weatherly’s early publications that, after all, represent the blossoming of an early Poetry Project aesthetics transformed into his own unique artistry:

levee music darky

levee music darky

eclectic blues guitar

every movie darky

every movie darky

eclectic blues guitar (93)

The book ends with “eclectic blues guitar.” This phrase is, alas, a final statement in print of an overall conceptualization orchestrated by Weatherly himself. He was our “eclectic blues guitar.”

1. Tom Weatherly, Maumau American Cantos (New York: Corinth Books, 1970), 29. “old envious blues feeling” is from Amiri Baraka, “Look for You Yesterday, Here You Come Today,” in Preface to a Twenty Volume Suicide Note (New York: Totem Press, 1961), 17.

2. Weatherly, Maumau American Cantos, 16.

3. Weatherly, Maumau American Cantos, 43. Tom and Carolyn had an apartment on East 5th Street between Avenues B and C.

4. Baraka conversation with author, Newark, NJ, early December 2013.

5. Letter to author, February 21, 1986.

6. Letter to author, May 13, year uncertain due to blurred postmark, sent from Birmingham, Alabama, with a Huntsville return address, hence probably mailed during Weatherly’s years after moving back to Alabama, although he made frequent trips back to New York City.

7. Weatherly, short history of the saxophone (New York: Groundwater Press, 2006), 73.

8. Weatherly, short history, 23.

9. Weatherly, Thumbprint (Philadelphia/New York: Telegraph Books, 1971), 15.

10. Weatherly, Maumau American Cantos, 11.

11. Weatherly, short history, 5.

12. Frank Wooten was a chef at the Lion’s Head in the West Village.

13. Weatherly, Maumau American Cantos, 45.

14. The great saxophonist John Coltrane.

16. “TPF” was the New York City Police Department’s Tactical Patrol Force. Created in 1959, all its members at least six feet tall, it was meant to battle rising crime but also political foment, specializing in crowd control. Eventually it became involved in political surveillance, which was a larger NYC police initiative. The TPF was a palpable presence in the East Village, at the time this poem was written.

17. Carolyn Samuels, Weatherly’s wife at the time. The reference is to Valley Stream, New York, on Long Island.

18. Lucy B. Golson Weatherly, Tom Weatherly’s mother.

19. The poem is listing streets in Brooklyn; “nostrum” is Nostrand Avenue.

20. Weatherly, Maumau American Cantos, Cantos 1–11, 33–43. Tom and Carolyn had an apartment on East 5th Street between Avenues B and C.

21. Thumprint, 29, 15, 16, 20, and 23, in order.

22. As in this from Weatherly’s midcareer, signaled in the word “crops”:

Art

for B.K.

elias built

model poems.

skies unlit

hotly vocal.

guise skill

crops trope.

Dated December 3, 1989, in a letter to author, envelope missing.

Edited by David Grundy