The dead and the living

Hugh Seidman’s late poems

In old age, many a poet ought to think twice before putting that last book together for public consumption. Easy enough to say — often the late work, when the poet had once published truly compelling, arguably great poetry, disappoints. I was in conversation with an elderly poet recently, someone who’s now in the eighth decade of life (as am I). We found we were harboring the same fear — we didn’t want to be repeating ourselves. We pictured rereading our late work and not seeing enough in it to warrant sharing it with the public. When we were young, reading Pound, our commitment was to “make it new.”

Adrienne Rich’s final book, Tonight No Poetry Will Serve (2011), was met with plenty of adulation. Nevertheless Julie Enszer, at the time, split the difference. The final volume, she remarked, “confirms as much as it departs” from what Rich’s readers had come to expect.[1] Stephanie Burt’s subsequent pronouncement, “[her] new poems show qualities that almost require the label ‘late style,’”[2] comports with Enszer’s judgment. While the “almost” is intriguing, Burt did characterize the collection as “explicit […] in its return to the poet’s prior work” — comparing Rich with Yeats. Why, then, the question? Do we rely on our great poets, still at work, to heed bounds we’ve set, our confidence in what we’ve celebrated, that toward which we look?

Yeats’s late work has of course been the subject of so very much, justly reverential, commentary. Peter Ure points out that the challenge for Yeats was “to discover his role in a universe” he “conceived” of “as a dramatic structure.”[3] Yeats confided to his diary that “one reason for putting our actual situation into our art is that the struggle for complete affirmation may be, often must be, that art’s chief poignancy.”[4] A substantial amount of Yeats’s late work is taken to possess a power and grace equal to that in his earlier poetry. Ask someone randomly about a poet’s late work; more often than not Yeats is mentioned.

I’ve thought a lot about William Bronk’s concise, dense, late statements. They don’t possess the majestic sweep of his poems at middle age (in terms of line length, overall volume, the philosophical punch in the solar plexus). Bronk’s late poems, however, hold their own, and they do seem typically Bronk. For me the comparison here is with someone like Harriet Zinnes; her late poems — their ethereal, sprightly, fleetingly brilliant statements seeming to have come from beyond the veil — are exciting in their exquisite lightness yet fascination that doesn’t dissipate. Zinnes’s last poems are supremely graceful, intelligent, paradoxically profound in their sheer defiance of gravity. Yet I’d not be surprised to find readers of her work, over the years, keeping to mind poems of hers written when she was at, say, full strength, which they know well, feeling the late poems to be a distinct leave-taking. They strike me as drawing upon the same wellspring of insight, finally, and as possessing an eerie gracefulness — less on display in her work of middle age, obfuscated there by something grander in presentation. That earlier work, not diminished by what would come, probably remains what her readers will embrace.

There’s another poet, Louis Zukofsky, needing mention in this context — as I think about Hugh Seidman, who is most noticeably Zukofsky’s progeny. The difference, when it comes to Seidman, among all poets, is that in a long and distinguished career, his greatest achievement is his last volume. In this sense, then, we can view Status of the Mourned, Seidman’s new book, and his career, apart and together, as something most rare. Published in 2018, in his seventy-eighth year and fifteen years since his last collection, this very late book, furthermore, discloses — announces — Seidman’s return to a poetics from which he’d strayed, once his friendship with Rich had blossomed.

As I contemplate the significance of this work that’s come very late in life, I naturally think of Tonight No Poetry Will Serve, Rich’s final collection, and of 80 Flowers, Zukofsky’s. Like Rich, Zukofsky was a poet who broke new ground. “Poem beginning ‘The’” was an inflection point along the modernist trajectory; 80 Flowers, considered to be an early postmodernist exemplar, has yet to be fully divined. Seidman’s late book includes poems about both his mentors, but it’s Zukofsky’s tenets that dwell within Seidman’s powerfully wrought lines. All the same, each elder is more than simply acknowledged. They help to create a historical tableau. By design, the book takes us back to Seidman’s youth, in order to move forward toward a present in which we witness the poet looking back, in reflection. This is an autobiography, and it is a reckoning.

The ordering of the poems historicizes Seidman’s poetic development. Perhaps it’s ironic that a few of them explicitly challenge the value Seidman himself finds in Objectivist poetics. First encountering Zukofsky in a class he taught at Brooklyn Polytechnic Institute, he solidified his bond with him. Seidman’s rendezvous with Rich was a decade off — that second, very important friendship, which is most sensed in the poems of his midcareer. I can’t help but see Rich pulling him, in some respects, away from Zukofsky. Yet Seidman’s spiraling back to his origins, given the longevity of his life, makes the homecoming possible.

But why, exactly, is this something I feel needs saying now? While Seidman’s last book is, I believe, his finest collection of poems, the peculiar grip it’s had on me has also to do with its intent to look back in old age, and to take stock. This is his seventh book; some poets (including Zukofsky and Rich), after well over a half century of writing, have amassed a much larger oeuvre. Seidman is frugal. This quality is obvious in his poems. The writing’s imbued with sheer craft and piercing intellect. Each syllable belongs right where it is. None of the poems is very long. All of them make room for the subtle percept. They’re meticulous statements, rendered in a refined prosody and shot through with obvious care.

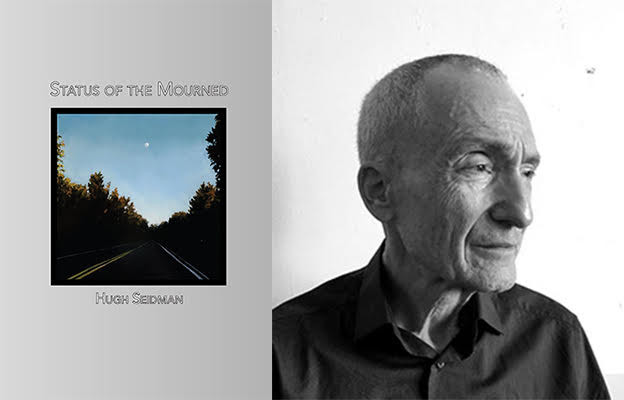

Readers long ago came to expect such a practice from him. Three of his six prior collections have won prizes. Now, after protracted silence, comes this work of unparalleled beauty. It’s ably complemented by a modestly affecting design. The front cover features a haunting painting by Jayne Holsinger: a landscape below an evening sky, the moon appearing just above a tree-lined, heavily shaded road. The painting’s mystery augurs what follows.

The other singular characteristic of Seidman’s work is its ethical imperative, which is couched in the question of how to live. In this late book the presence of death is palpable; so is a commitment to being alive. The duality runs throughout the book and forms the tissue of human relationships. Seidman gives us an honest, tender, and harrowing accounting of the living and the dead, who they are, and he strives to do the same for himself. His judgments are unadorned. To read them is to exult and weep. Family and friends are glimpsed and considered. In past and present, people live and die within the built, implacable city. Manhattan landscapes sustain the delicacy of memory — within a fading world. Remembering affords clarity. Vital sightings from the past are a necessity.

The status of the mourned is a conceit whose vector courses in either direction. In the title poem, “Seido Karate: ‘Kino Hito No Mi Kyo No Wagami,’”[5] we look on Seidman as he is meditating with others in their dojo, while a sensei struggles against a life-threatening illness:

butt on heels, right palm up in the lap under left knuckles, thumbs touching

I shut my eyes and shot a ray of invisible light to Beth Israel hospital

to the first female sensei — as the Master had instructed

tube-entwined, eyelids fluttering under the morphine — she had not known him

and then we stood when he struck the gong

and the tears arose that I would not have accorded myself

as if then for her with whom I had no connection[6]

Seidman grieves for those gone, witnessing his own bereft state; “amid the remarkable fervor that raises the dead to the status of the living,” he loves those here. His poems embrace each status. (The word status, the diction here, is curious in its abstraction, possibly suggesting the extraneous nature of circumstance, in juxtaposition to something elemental.)

In counterpoise, the poems dwell within the dead’s hold upon the living. The depth of one’s love for another is contingent upon keeping faith with the other’s human frailty. Its constancy is dramatized in the book’s first poem, entitled “Old Letter,” which conjures Seidman’s father. “Lava” follows it — meant to recall his mother. The two poems are a set piece. Symbolically, the parents will give birth to the remainder of the book. Here’s “Old Letter” in its entirety:

Passion of the written when all whom I knew were alive

Helping you will not in any way burden us in any way whatsoever

Like the theory of the future of the visible stars

So far-flung in the blank sky that their light will not reach us

You being happy makes us doubly happy

You are our life and joy — no matter what the psychology books say

And my father in motion fated like the voided stars

One who has gone light years by now — who would help if he could (3)

The first line of “Old Letter” inaugurates the remembrance of Seidman’s parents and establishes the entire volume’s premises. The poem reveals an aching disappointment that the son still feels, yet preserving his love for his father (who didn’t want him to become a poet).

Seidman understands the limits of personality, human will, and action. “Lava,” the second poem, resuscitates his mother, who suffered bouts of profound depression and stints in mental institutions. The poem discloses the story of her vacancy in his youth, depicting a mother at war with her very young child:

Six-month, street-ditched tot.

Psycho mom walks off.

ECT tit swapped for Dad.

Talk about mixed metaphor!

Shocked Mom comes home.

Babe’s bed at parents’ bulb.

Past it, Freudian strobe.

Had that shut sonny up?

Did not talk until three.

Doc said: a spew, if ready.

Yes — fire smart, avid.

Cooled to paradox of rock.

Yet Mom spat: rotten brat.

E.g., babe nixes galoshes.

But — why not rebirth?

Not the re-screwed watts. (4)

The outrage over what is clearly the woman’s neglect of the toddler hammers at us in Seidman’s brief and taut, pulsing lines. Psychological cleaving between child and parent places any hope of happiness in jeopardy. Time is depicted as both physical and emotional distance, through the poem’s jarring observations made palpable by its muscular rhythms (e.g., “Yet Mom spat: rotten brat”). “Lava” is suffused with the grown son’s disgust and sorrow.

The opening lines of “Lava” look ahead to several other poems in which Seidman is also watching people who frequent one or another of his city’s pocket parks or playgrounds: an “Old woman in black on a bench,” her “Shopping cart like the metal wheeler given a neighbor” who “[fell] in the street,” Seidman confides, is now “afraid to go out.” The surround envelops them all — private and public in shared space — the city possessing its own living, frenetic pulse. It’s as much a life force as anyone in it, a place where everyone watches everyone else. He enjoys the park’s “last-of-April tulips” that are set against Manhattan’s towers, their “sky-high-rent” in this “world-wide-tourist center of the universe” (42). People congregate in streets and parks hugged in by buildings. Everything’s held in the moment by the city’s rhythms. Beauty and callousness meet amid the noise of traffic or in relative calm under a few trees. The flaneur intersects it all.

Seidman, who sees in the present and past at once, starts in physical place and transports us through reverie and reflection. “Crossing Bryant Park” transcends the present moment to eulogize his deceased friend, Susan Robertson. In the poem, Seidman’s on his way through the park to his job. He walks along, “1200 steps to work,” going back decades to Robertson’s “bridal two-step”:

Father: suicide; Mother: survivor; Sister: fatal breast.

Tai chi fighter, shrink, scholarship Bryn Mawr waif.

Lungs sicker than said or known.

Phone small talk — then you were gone. (30)

Illness is irrevocable. Seidman recollects her “noduled, cut out womb” and a “[t]ransfusion, perhaps, the future tumor root.” No relief from the suffering is on offer. A noble and beloved human being disappears.

Seidman’s greatness as a poet ultimately lies in his capacity to identify with the other. Suffering rivets him. Compassion fails to ameliorate it. And so he’s thrown back upon a bare sense of moral urgency. The problem of the random universe is that there is nothing, no moral framework, no locus, nothing to hold onto against the wind from a black hole. His poems, however, stand in defiance of that, as in “Writing and Catastrophe,’” in which “[t]o exist is to be guilty” and “[t]his is the black hole of morality.” The poem’s opening movement defies the reader to forget and brings us all to account:

Albania, Kosovo/Kosova, Lebanon, Nicaragua, Pakistan

No poem post “holocaust”

Irony shuts up

Body unable to speak on atrocious Earth

No poem sparks the gap — universe-narrow, atom-wide —

Between act and word

Some lover enacts no difference

Eyes bleeding, palms budding stigmata

Modern life is the “Radio alarm buzzer” that “wakes the justice by the torturers” (43–44).

Another of Seidman’s eulogies is for Marla Ruzicka, who founded the Campaign for Innocent Victims in Conflict (CIVIC). He depicts her as the young American woman she was, who perished at thirty in Baghdad — “her last outcry: ‘I’m alive.’” The poem’s extended incantation, made up of literally searing images, details how she would place herself in harm’s way:

sparks rachet from the tinder

crackle from the racket of fire and light and are gone

tireless, fearless

against generals, bureaucrats, politicians

her skull touching skull

hem of her black abaya clenched in her fist

set on the shoulder of the unveiled woman in hijab

who buttresses the dark-eyed, moon-eyed child

corpuscles hiss from the splutter

flare from the pyre drafts

motes rocket, incandescence, and are lost

flecks tick from the holocausts

ingénue face-splitting smile

Buddha-girl California smile

petite with curly blonde tresses

pretty, peppy, fiery, vivacious

nicknamed Bubbles in Kabul

immolated by a God car on the Baghdad airport road (45)

In “Millennial,” portraying a similar situation, the lack of self-regard has become a necessity. “Millennial” takes us further back in time, to the Vietnamese Buddhists who set themselves aflame in protest against America’s disastrous war in Southeast Asia (the footage of their suicides ubiquitous, then, in the American media).

What was Seidman doing while people burned? “I programmed a mainframe,” he concedes. He was “[d]eferred for ‘critical skills’”; at the same time, a conscientious objector performed “alternative service,” though much the same kind of thing. In Seidman’s genteel naiveté, what was left for him to ponder then — and now — is the moral precariousness of that life. Throughout history we find human cataclysm:

What did I know of war?

A brother-in-law’s M-16.

Words like the fires of Dresden.

(Put, struck, swapped.)

Car bombs leave me whole.

What eye for what eye?

Debris of the universal Kaddish.

Blaspheming local death. (36)

He won’t absolve himself. “I confess that I confess,” he declares in “Unfinished Poem” (47).

Yet forgiveness takes one but so far. Among several remembrances of Ed Smith, Seidman’s oldest and closest friend, there is “Grand Mal,” the group’s linchpin, in which Seidman realizes his utter helplessness. The poem’s metaphysics is nearly intolerable. His despair is his genuine form of love, as he looks on at his friend’s death throes:

salt water wracking metal

salt water rupturing buckled metal

a melanoma a frothing at the mouth

eyes rolled up into the head

the convulsed ocean the metastatic sky

conjoined to the tumoral brain

cremation ashes beside a bed

glacier melt thinned-out beaver pelt

sand foam churned by the salt

Pied Piper child shut in the wave (17)

Seidman’s grief is the grief of the world. A particular trope, which recurs throughout the book, materializes in “Grand Mal” in the phrase “buckled metal”; it emblematizes Smith’s defeat.

The world’s elemental, huge forces mimic Smith’s primal fight, in the poem, simply to breathe. In comparing the fundamental condition of human struggle with vast exterior forces — “convulsed ocean the metastatic sky” — Seidman portrays a parallel, gruesome drama: oceans have ebbed, flowed, and surged, well before humans’ presence; the single human life might end without hope or dignity. There is always the possibility of human extinction.

And there’s no recourse to Smith’s calamity other than Seidman’s impulse to answer for it as if somehow responsible for the wretched end. His intolerable dilemma is expressed succinctly in “Frank Canned, Joe Upped” — another of the Smith poems, as a single, self-sustained line, and as a non-sequitur: “Rage: a steel bar to bite” (7). The line floats alone, on the page, between couplets. Its density, like the compression to be seen in a poem such as “Marla Ruzicka,” drives home the existential atrocity residing at the core of “Grand Mal.” The “steel bar” becomes the “buckled metal” of the later poem (metal punning with mettle).

This trope’s subliminal associations will arise in still another poem, titled “Melancholia,” which also anticipates “Grand Mal”:

On Ed’s way out I bragged: I found the path.

Muzzled the black pit bull at 70-plus.

Tumors in the head of my boyhood friend Ed.

Three-scalpeled, three gamma-knifed.

Metatastic melanoma — then, the grand mal.

Suddenly the ambulance woke me for a while.

Irony of Ed: Columbia imager of brains.

Claremont home hospice — a “life,” as is claimed.

Ambition that enacts the acts of its plan.

To love, to work — for as long as one stands.

But underworlds smoldered and flared.

I could not forget what I could not remember.

The black pit bull again licked my hand.

Manic tongue of the clamped, adamant jaw. (13)

The “clamped, adamant jaw” is the earlier poem’s “rage,” the bitten “steel bar.” Seidman’s loss is irremediable. And in Status of the Mourned Smith’s death looms so large that it becomes, in essence, the subject of the entire book. The poems about his cancer remind us of our modern affliction. The ministrations of contemporary medicine become their own insults, beyond the disease.

Suffering, which must result in death, becomes Seidman’s absolute zero. “I did not understand a good death until my friend died and I had no friend,” he avers in “Testament” (14), never looking away from the torment. Through loss, however, he holds himself, and everyone, within the human communion. Dying with dignity becomes paramount.

In “Envy,” a sardonically playful, bravura performance, he is the object of castigation for his self-involved aspirations:

Once: Musketeer, soul chum, “brother.”

Then: self-exalter, cocksure strutter.

No nameless Midas met minus a glance.

But galler, compeer, top dog, shunner.

I glared from that skewed level.

One foot in the present, one foot in the past.

Sane brain urged: let other prosper.

One wins today; one, tomorrow.

Instead: I signed the chit; I bought the myth.

200-dollar Brioni marked 29.

Silk treasure, paisley verdure.

Four-in-Hand, Pratt, Windsor, Half-Windsor.

Narcissus: unbudged, mirrored.

Knotted, noosed cravat at buttoned collar. (10)

Here, in arch irony, his vibrancy has blinded him to the importance of friendship. Seidman’s sense of regret and self-accusation shaping “Envy,” in some respects thematically resonant with “Melancholia” and “Frank Canned, Joe Upped,” subtly, indirectly shares something else with “Grand Mal”: the horror of one’s undoing.

“Envy,” furthermore, is meant to stand in contrast to several love poems to Holsinger, Seidman’s wife. One of them, “The Longing of the New World for the Old World,” completes the book. This poem’s placement is also intended to serve as a counterweight to the two poems about Seidman’s parents, which open the book (particularly “Lava,” recalling his mother). The final poem, for another reason, rivals “Grand Mal,” serving as a kind of antidote or salve. The poems to Holsinger affirm the will to live and to live well — to live meaningfully, even in the presence of calamity — or alternately, as this poem demonstrates, in the triumph of happiness.

“The Longing of the New World for the Old World” is magisterial. Complex and sweeping, this final poem gathers all of the book’s concerns. The poem’s setting is the shore of the Hudson River in lower Manhattan, near the island’s southern tip. Across the river, Seidman can see “the far-shore monoliths” of Jersey City; slightly to his left, toward the open sea, there’s the Statue of Liberty, and then the harbor.

The poem begins with a phrase that will become the speaker’s refrain: “I keep my post for you at the harbor of the new world.” Holsinger is embarking for Europe. He’ll stand where he can see the ships entering from the ocean. “I go down at dusk,” he tells his absent spouse, “and watch the sun drop.” The lines suggest how this last poem is meant, figuratively, to be a paean to the world itself. In effect, they’re a declaration of love. They spell out Seidman’s devotion to Holsinger, yet their expansive nature comprehends a great deal more. And they sum up his life: “My father landed a hundred years ago from the old world. Take care, come home, as they say, safe and sound. // I keep my post for you at the bend of the continent” (71).

The poem’s grandeur — emerging out of time and place on the one hand, on the other out of love and commitment — is enacted through long lines that contrast the book’s typically shorter lines and compact statements. Seidman’s words seem to expand to something much larger, in any case, within which Holsinger is central. The poem concludes much as it began, coming full circle not only to its first lines, it’s implied, but also to shared and abiding concerns arcing across all the poems:

I will think of you in the old world as I stand in the new world.

This poem conjoins to the absence of Mother.

This poem creates itself as the absence of Mother.

No reason for the poem but the absence of Mother.

No refuge from the absence of Mother but the poem.

I breathe the dark of the water that covers the last of the sky.

For what do the people of the old world long?

Why do they show the American film in the park below the Ferris wheel

in the Prater?

I keep my post for you, my river post. (71–72)

A poem like this, its capacious nature, was not possible for Seidman when he was young. However, condensed, staccato-like lines such as we read in “Lava” (“Six-month, street-ditched tot. / Psycho mom walks off.”) are reminiscent of what he was doing even in his first book, Collecting Evidence (the 1970 Yale Younger Poets selection). In a way, Status of the Mourned returns to where Seidman began, albeit with greater sophistication and wisdom. The closing of the circle comports with this book as a true, faithful summation. Seidman has come to terms with his entire life, in retrospect.

Integral to this life has been his relationships with other poets and their work — most of all Zukofsky and Rich. Status of the Mourned, containing a sizable number of poems written about or to each of them, also simulates them in the persona’s acts of address. The inclusion of these poems can’t help but raise the question of a poet’s late work (as Seidman must be aware). The new book, a testament, interweaves or merges autobiography with impartial observation. A particular irony is that when he looks back at loved ones he sees their imperfections and failures along with their victories.

Seidman met Rich in 1967, when he took her MFA class at Columbia. He’d met Zukofsky in 1958, when he was still quite young and therefore more amenable (than he would later be) to Zukofsky’s understanding of poetry — his Objectivist precepts undergirding the appropriately titled Collecting Evidence. Although it molded his foundation, Seidman managed to throw off the clinamen of Zukofsky’s monumental achievement and ego, to develop his own distinct poetry. It doesn’t seem out of the question that Rich’s tutelage was of help in this way. Still, whether or not he was a second son for Zukofsky, Seidman took that role for himself.

The poem “L.R.” replicates the rhythm as well as the form of 80 Flowers, whose first lines are “Heart us invisibly thyme time / round rose bud fire downland.” Seidman reconceives the poem’s proceduralist method of five-word lines as a kind of salute:

Forked sycamore gores the moon.

Piebald bark wrinkled like skin.

Notch between here and there.

Gash between now and then. (25)

What was then is again now.

Zukofsky had advised him, as Seidman once put it to me, to “cut cut cut.” He later remembered Zukofsky’s approach to poetry as “not foreign to me since I was already involved with the paring down of mathematical proofs.”[7] All in all, his teaching was “an accumulated gesture.” Taking Zukofsky as his “poetic father,” Seidman strove “to imitate” what he was being drawn to naturally — that “spare, precise style.” He later declared: “I must simply say that I loved him.”[8] The musical, linguistic virtuosity, most salient in Seidman’s late collection, comes from their relationship. The book can’t help but make reference to that both explicitly and in the poetics on display in it.

Full-stopped lines are the norm here. They underscore concision as a daily practice. Seidman’s elegance has always resided within the empirical, despite the spaciousness of the mathematical, and the book maintains a fierce commitment to specificity. The result is disclosure of delicate truth not normally sensed in the tangible world. (Perhaps, at heart, this has been the allure of Objectivist poetry.) While Status of the Mourned is at heart an autobiography, the vocation of poet is central in the life — and poetry may, like mathematics, invoke something else.

There’s a slew of poems about Zukofsky in the book. And there’s a wonderful two-poem sequence about Rich. She’s admired. To a degree she’s turned into a martyr and worshipped. Seidman employs italicized phrases, in his diptych to her, meant to reproduce portions of her poem “Tear Gas.”[9] They reflect his own corporeal ethics evinced in his title poem, in which he describes himself as “[sitting] seiza before kumite / upon the track to no end but the speed of the hurtling body.” Addressing Rich directly, in the first poem of the sequence, titled “In an Ill-Lit Formal Space,” Seidman recalls her efforts just tobe taken seriously:

your stare almost mocks us

your stare is the four-year-old

locked in the closet

beating the wall with her body

second photo: Berryman, you, Mary Jarrell

(a suicide, two suicide widows)

female prodigy fronting the phalanx:

seven dark suits — Kunitz to Penn Warren

privilege to expunge yourself

freedom to renounce the dead (69)

Seidman may recognize in Rich his own image, as that of someone whose early years were filled with trauma, for similar reasons. In any case his life as a poet is integral to a moral kinship he has with Rich. Both lives are possible, finally, only because of the vocation of poet. Whether or not poetry heals wounds is another matter. “I labor,” he tells her in the final line of his homage, “because of you with the hope of poetry.”

His homage to Zukofsky is more complex. And, as in “Zuk Tape,” Seidman offers something still more intimate. The poem begins with suspense: “Bill Z’s note: Hughie here’s Louis / Craving solace of his voice (decades unheard).”[10] Similar to Seidman’s “Two Poems” to Rich, each of the several Zukofsky poems acts as an element within a lengthy meditation on the elder’s work, its legacy, as well as Seidman’s attachment to it. The italics in “Zuk Tape” convey — as they echo the titles and lines of some of Zukofsky’s works — the sense of an ongoing inner dialogue. This is especially the case in the poem’s middle portion where the poem’s speaker gets lost in rumination:

Lines in my head all my adult life

Blown-dust texts pulled from shelves

Shorter Poems

(“Hear her clear mirror”

“Come shadow come”)

Bottom

“A”

Catullus

(“Miserable Catullus” to “Miss her, Catullus?”

Paradigm of his speech/song poetics) (62)

Among the works Seidman mentions is the vivid, magically supple, and succinct lyric “So That Even a Lover.”[11] Midway through “Zuk Tape” he pivots to an admission, which ends with the poem’s delicious punch-line (the italics are Seidman’s):

Objectivist?

That was forced on me

I had no program

It was all very simple

You live in a world

I don’t see how you can escape it

Even if you escape it

You’re still living in some kind of situation

You make things in it

You make it with the tools of your own particular craft

In this case words

I feel them as very tangible

Solid so to speak

Sometimes they liquefy

Sometimes they airefy

But those are still existent things

(And finally after 40 years

I catch “little wrists”’ sexual “do”) (63)

What comes across in the suite of Zukofsky poems is a picture of Seidman, a highly accomplished poet looking back upon three careers, and coming to a resolution about his poetry as well as poetry itself. This entire configuration is held by one or another form of memory. To remember, for Seidman, is also to ponder the lifelong vocation of poet.

What could it mean to “labor” in obscurity? Zukofsky had done so and was profoundly disappointed by that. Seidman ends his poem “L.Z.” (echoing Zukofsky’s purposeful echoes of Shakespeare) like this:

Failure has nothing to be lost.

If bile offend, shall love deform?

Happiness/unhappiness — the great tautology.

Lineage master of the song.

So-called cup of bitterness.

Three times full and running over. (61)

“So-called,” indeed.

1. Julie R. Enszer, “‘Tonight No Poetry Will Serve’by Adrienne Rich,” Lambda Literary, February 7, 2011.

2. Stephanie Burt, “No Scene Could Be Worse,” London Review of Books34, no. 3, February 9, 2012.

3. Peter Ure, “W. B. Yeats: The Later Poetry,” The Review of English Studies16, no. 63 (August 1965): 328.

5. The Japanese phrase can translate, roughly, into English as “yesterday the other person, today myself.”

6. Hugh Seidman, Status of the Mourned (New York: Dispatches / Spuyten Duyvil, September 2018), 16.

7. Emails to author, October 11, 2009, and December 29, 2018. In an interview, Molly Nason asks, “You went from mathematics and theoretical physics to writing poetry. What caused that shift?” — to which Seidman explains as follows: “I started writing poems and also became a lover of mathematics at around the same time, at about the age of 14 — i.e., the age of puberty. Before that I had been a kid growing up on the streets of Brooklyn. After that I entered, for good or bad, into the life of the mind. And, I did not give up one (math/physics) and start the other (poetry), but rather I had been doing both all along.”

8. Hugh Seidman, “Louis Zukofsky at the Polytechnic Institute of Brooklyn (1958–1961),” Louis Zukofsky: Man and Poet, ed. Carroll F. Terrell (Orono, ME: National Poetry Foundation, 1979), 100.

9. The will to change begins in the body not in the mind

My politics is in my body, accruing and expanding with every

act of resistance and each of my failures

Locked in that closet at 4 years old I beat the wall with my body

that act is in me still[.]

10. “Bill Z” is the poet Bill Zavatsky.

11. Little wrists,

Is your content

My sight or hold,

Or your small air

That lights and trysts?

Red alder berry

Will singly break;

But you — how slight — do:

So that even

A lover exists.