Everything’s in flux

On Jeanne Heuving’s ‘Indigo Angel’

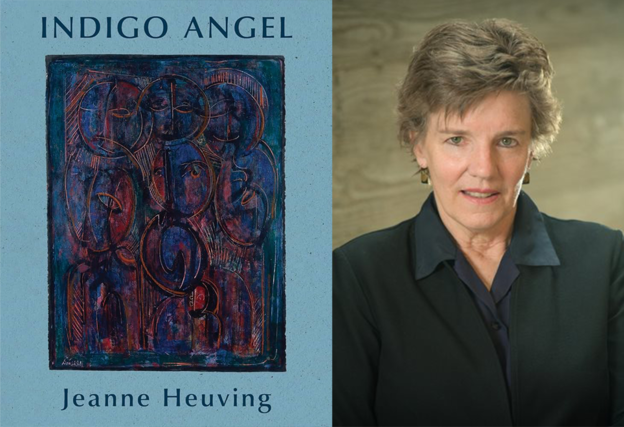

Indigo Angel

Jeanne Heuving

Black Square Editions, 2023, 220 pages, ISBN 979–8–986036–91–5

The well-worn apothegm text, texture, textile gets reversed in Jeanne Heuving’s remarkable new book, Indigo Angel, which is comprised of three long poems that, read as one, become something greater, much in the way the ecology of a place gives rise to a human drama, our civilization’s history unfolding within a natural order. Indigo enabled the emergence of literacy. Integral to how we now understand the noble or cruel human being, indigo, through happenstance, became the ink with which complex, sometimes profound, musical compositions as well as works of literature and art have been created. Indigo, to be sure, has made human dignity more than just possible. It’s the spine of our human story, having held our human contradictions in stasis. As a marshy plant, refined ink, the color itself — indigo has disproportionately shaped our lives.

Directly or indirectly, indigo has led to Heuving’s creation of this marvelous book that’s very much about great art. It drives her eloquent portrayal of how modern jazz came to be, and what our world, in its better versions of itself, has become. The three long poems that make up her book are inspired by three iconic, modern jazz classics: Duke Ellington’s “Mood Indigo,” Thelonius Monk’s “Brilliant Corners,” and Henry Threadgill’s “Air Time.” Fundamental to Heuving’s architecture, these great musical renderings allow the serious listener of jazz, really any serious reader, to reconcile America’s original sin. Brutality and splendor, coeval manifestations of a zero-sum, unavoidable present, figure in human debacle as well as triumph. All three jazz masterpieces, which cannot but help to recall our slavery past, stand apart from but are part of the ecological history Heuving foregrounds in Indigo Angel. They strike me as inevitable, while the culture that gave us this music is sui generis. With the end of systemic slavery, over a swath of time, jazz would come into being; this melodic drama recounts what led to its creation. People sometimes have the blues because of the accident of indigo.

The throughline of Heuving’s book is the history of Western expansion, as a consequence of international mercantilism. Our past involves human and nonhuman synergies; they now figure in our artistic ventures. Heuving’s persona guides us through the scope of this book in lilting cadences, and is reliably intelligent and informed. It imbues our history with a striking immediacy. The book signals Heuving’s allegiance to the epic mode — its first words are “To begin with ink,” evoking Genesis. Yet she’s confiding in us. Here’s the opening page in its entirety:

To begin with ink. I scratch my paper with pen, making abrasions, little torn pieces of pulp, ink soaking into fibers. My hand moves down the page, ink marking its passage, seeming ahead and behind it. Inks are very low-lying grasslands subject to flooding by tides. As the salt water rises and seeps into the grass and then quickly covers the depressed land, it makes inky pools of green, combed in one direction with few entanglements. Almost a true level between land and high tide makes for a rich sea marsh, lower by a foot or so, nothing but inks growing on it. Some of

Heuving’s ragged right-edged, seven-lined prose unit — the building block of our readerly experience — is centered within the page’s white space as part of the book’s gorgeous design. The fabulous painting on the front cover, Masks on Parade by David Driskell, seems to determine her overall poetical conception (whether one reads the painting allegorically or simply as colorful patterning). The book’s tactile nature — the sense of its material prose — complements Heuving’s narrative timbre. The primal, recurring scene of the poem is that of our narrator — a writer who happens to be writing out of a specifically physical, sentient experience, possible at a marshy shore; she looks out, from San Juan Island, on Puget Sound (originally named the Salish sea). Humans made ink by imitating what happens in the marsh of life. Nothing stays as it is — everything’s in flux — like the inventive surge of jazz.

Heuving’s favored rhetorical mode is contemplation, which includes her reflexive awareness of what and how she’s writing: “To begin with the literal,” she says; “I wish to shore my writing within the littoral.” “The littoral,” as she instructs us, “is the shore between low and high tide or the bog of a river or lake”; the littoral depends on the “tug of the moon.” This, in turn, “powers the tidal mixing of saltwater and freshwater in an alchemical exchange.” The intriguing metaphor here, “alchemical,” is key to human presence within the ecosphere.

Some jazz compositions are shaped by “littoral drift” where the shore’s “sediment [is] moved by the current onto sandy beaches” — blown about, displaced within a grand symmetry: “Oblique winds generate a current parallel to the coast, sending/ sediment in a swash that then reverses in a backwash.” Drifts, swirls, and floods half-rhyme with each other (note the delicately positioned “swash” and “backwash”). Their ontologies compel the true story forward. The rhyme — “literal,” “littoral” — reminds us of the necessary observer. She’s weaving her “text” into the “textile” of her poetic language; the “textures” of it contain the poet’s voice. Her narrative of this journey requires “the figurative loom as well as actual pen, paper and ink.”

Mood Indigo, the first of the book’s three sections, starts the story in medias res, long after the demise of the Middle Passage across the Atlantic to the Americas, which is, in essence, the story of the modern world. The emergence of jazz — America’s art form forged from the grief of slavery — consists of blind hope too. Heuving’s attention narrows to the American experience that’s grounded in what seem to be internal inconsistencies: grace/ruthlessness, love/depredation. Heuving moves toward her meditation on “Mood Indigo” by first taking stock of the materials and circumstances that make up the greater context. In her capacity to take in the larger history, the point of view of her persona, standing at the edge of a marsh, becomes central. She begins from within the conditions that give rise to a material and artistic culture.

Yet Mood Indigo looks ahead. As in Genesis, our procreative poem par excellence, we must begin at the beginning. Just so, the artistic text, its expression of the human condition, materializes through the manipulation or repurposing of nature. The act of weaving a text, as Homer’s Penelope exemplifies, is mundane and important. Paper — etymologically from papyrus, a textile — preserves the written poem as art. The book’s second and third sections — named for Monk’s “Brilliant Corners” and Threadgill’s “Air Time” — are a continuation of Heuving’s thinking; they complete the ensemble, the three musical works seeming to belong together, each exemplifying her persona’s thoughts.

The singular horror of the Atlantic triangle — harvesting and transporting human cargo to American shores — is paradoxically embodied in Heuving’s steady, contemplative present tense that, in cyclical motifs, comprehends our past. Her epic narrative is quite other than Homer’s. Together, her three long poems constitute a revelation — and Indigo Angel favorably compares with other recent imaginative forays into the same large subject. In M. NourbeSe Philip’s long poem, Zong! (2011) — about the fated voyage of the slave ship Zong, whose captain ordered 150 of its prisoners be thrown overboard to save drinking water (the ship’s owners collected the insurance money) — her use of white space is dramatic and, as is true of Heuving’s poetics, commensurate to the enormity of the crime. So too Kara Walker’s 2014 installation, “A Subtlety, or the Marvelous Sugar Baby” — a seventy-five foot sculpture made of sugar depicting a nude and kneeling, sphinx-like, young African woman — inside New York’s abandoned Domino Sugar factory. When slaves were offloaded, the ships then took on sugar to be delivered to European ports. Hilton Als describes the figure’s posture as regal yet totemic of subjugation, “beat down” but erect. He situates the figure historically as part of what, at the time, was called “that peculiar institution” of sugar sculptures fashioned by northern European chefs prized for their artistry. “[S]ugar is brown in its ‘raw’ state.” There was a tradition “where [these often] royal chefs made sugar sculptures called subtleties. Walker was taken not only with [. . .] stories” such as these, “but with the history of the slave trade” in which sugar cane was a staple. “Who cut the sugar cane? Who ground it down to syrup? Who bleached it? Who sacked it?” (The New Yorker, 8 May 2014).

Heuving’s more sensual work, in its lyric intimacy provides a philosophical framework within which we comprehend nothing short of a civilization’s transformation. Her extensive historical contextualizing almost disappears in the book’s sheer poetry, as if fact will always be overcome by beauty (similar to how, in John Keene’s historical fictions, for example, their chronicles threaten to obscure their plots). This is an exceptional pleasure.

The text — of poetry, art, music — is Heuving’s ultimate fixation. Meanwhile, her reader feels and understands the depth of sorrow in, say, Fats Waller’s 1929 hit song “Black and Blue” (its searing lyrics by Harry Brooks); recordings of it continue to be released: “Even the mouse ran from my house, / they laugh at you, and scorn you too / What did I do, to be so black and blue?” The blues. Indigo. Out of our crude, debased selves, we somehow find love. “Black and Blue,” “Mood Indigo,” and other seminal compositions of American jazz began their lives long before these songs themselves were created.

Heuving’s grand vision of our history, which she literally grounds in our intervention in nature, finds the natural in what’s otherwise artifice. That there’s some kind of eternal-seeming balance amongst all these forces and facts is borne out in the waves and rhythms of her mellifluous talk, her assiduous story-telling: the story of the human life–world as related from the perspective of someone who watches at the marshy shore, where there are only thresholds. Nothing stays as it is; everything is in flux — which may be, for Heuving, the essence of jazz.