These poems are loaded

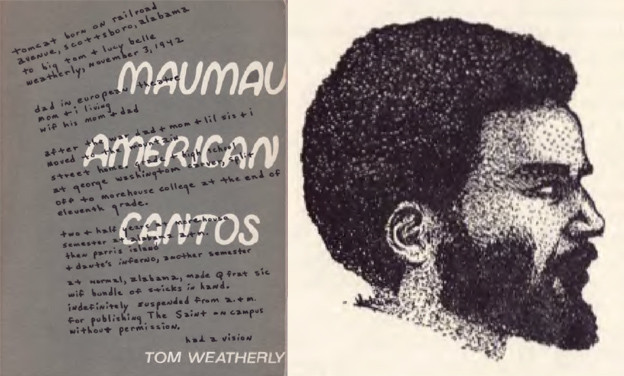

Editorial note: What follows is an excerpt from a review Stephens wrote of Tom Weatherly’s Maumau American Cantos and Andrei Codrescu’s License to Carry a Gun, a review originally published on page 6 of The Village Voice on December 31, 1970. — Julia Bloch

In the winter of 1968, LeRoi Jones went on trial for possession of guns in Newark. At his trial, the judge cited three poems that had appeared in Evergreen Review as evidence of the defendant’s guilt. A flyer circulated showing Jones handcuffed, wearing a prison uniform, and sporting a gash down his forehead that obviously hadn’t resulted from hitting his head on the typewriter. The caption read: “Poetry Is Revolution / Revolution Is Poetry.”

These two books share the same radical energy with the events that occurred around that period. One has to do with a black poet experiencing America; the other talks about guns, the weapon as metaphor. There are no silver bullets in either book — their arsenal is heavy artillery.

Both Tom Weatherly and Andrei Codrescu are religious madmen and lovers. They are men who have inherited haunting sexual dreams. Their poems are communicators of these fierce dreams. There is nothing vicarious in either book. Sexual passion is manifest in healthy, vigorous, uncontained terms.

d b a rider

ginger hips bred

you said

captain easy

go down on

river hips

new orleans

louisiana

where my mouf sings

a goat song

(th chorus line.) (Tom Weatherly, canto 9)

[…] Here are ravers, shouters, cursers, blasphemers, but mostly gentle men; there is dignity in the lyricism they use to talk of women. The best poems in each book are usually love poems, written with a tenderness and delicacy which betray those cults that make objects of women. This work has nothing to do with popular culture, media fads, or hip postures. Both books chisel at the foundation of American literature, carefully undermining archaic poetic constructions, but so subtly the reader never knows what hit, who struck first, the poet or his poem.

Weatherly is a poet from Scottsboro, Alabama. I first read his poems when we hung around the St. Mark’s Poetry Project. I can’t pretend to be objective about his work, because I’ve sat in rooms with him as he was writing many of the poems in this book. Maumau American Cantos are compressions of the feelings that passed through Tom during those days, when the only subjects we could talk about were poetry and revolution. Those were our two obsessions and they remain the poet’s concerns in his first book.

dip shit mothafuckn blood

suckers, stuff the ballot, drain

the treasury, increase taxes

[…] as you can see yourself, the language is,

your politics aint the moral.

The author being black, Southern, an ex-minister, ex-marine, but mostly being black, anger is a root emotion in these poems. The first poem in the book, “autobiography,” gives a sketch of his life and upbringing. That is a relatively quiet poem, but there are boiling points in this book where even poetry fails, where the poet relies on pure rage to sustain his measure. Other poems return to lyricism; they are poems of bewilderment, humorous in tone, the best being part 3 of “roi rogers and the warlocks of space”:

hadassah leavenburg

baby you’re selectd

marry me in my pre

fascist period. why

because i

dig yo fat

thighs

rumpd ass

bald domed tits

cunt that’s a live

home to huge beasts.

we be fuckn kosher

’til i find what

shine means.

It is impossible for the poet to be objective about a culture that annihilates his sensibilities, kicking him first, then soothing his battered psyche with a grant, a job, an honorary degree. I doubt whether Weatherly would talk if Dick Cavett, David Frost, or Johnny Carson invited him on their shows. I picture Tom mumbling his answers, not allowing his words to be understood by men with empty souls, no souls, or eroded ones. Some poems are written from this vantage, being obscure to the point where his private shorthand defeats the emotion he wishes to portray, but most of the time his abbreviations, jargon, private puns work.

Edited by David Grundy