Essay with Tom Weatherly in it

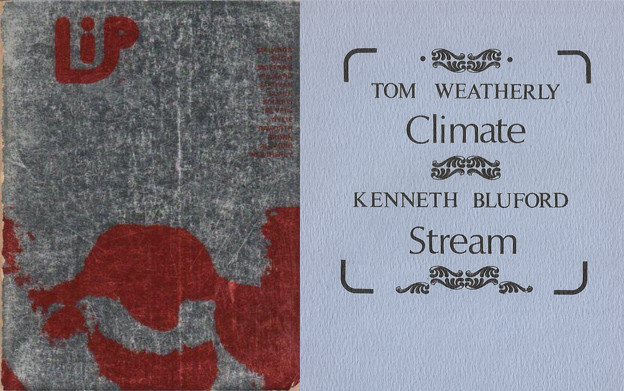

Note: This essay appeared in the first issue of Lip magazine (1971), published by Middle Earth Books and guest edited by Victor Bockris. Other contributors included Gerard Malanga, Patti Smith, Tom Pickard, Aram Saroyan, Tom Clark, Andrew Wylie, Tom Raworth, and John Wieners. Bluford’s essay appears on pages 99–106 and accompanies a series of poems by Weatherly entitled “Weather,” which includes additional Maumau American Cantos, some of which are earlier versions of poems that appear in their final form in short history of the saxophone. The photographs of Weatherly and Bluford by Victor Bockris that form a part of this feature were taken on the occasion of “A Reading in Celebration of Lip” by Weatherly and Bluford given on November 19, 1972. For this reading, Sam Amico of Middle Earth Books put together a now extremely scarce pamphlet entitled Climate/Stream, with five poems by Weatherly and five by Bluford. — David Grundy

From West Africa to the West Indies to the Deep South and up North, black American folk art has evolved into a complex development, a house of many mansions, containing multitudes. Flesh and blood of African and West lndian rhythms and modulations were retained and reinterpreted, the body of Southern cries and hollers, work songs, ringshouts, sermons, and shouting spirituals preserved as a natural resource, and Protestant hymns, European melodies, the instruments and styles of Civil War marching bands, all were salvaged and made the living property of minstrelsy, the blues, ragtime, and jazz. Music running through their heads, Paul Laurence Dunbar and Langston Hughes tried to bring about a fusion of white literary forms and black sensibility and idiom, and their successors in 1972 are still trying. Scattered returns: jazz greats like Horace Silver, Ornette Coleman, Archie Shepp writing lyrics; the Last Poets, Michael Harper, David Henderson, Nikki Giovanni making records with choirs, congas, and bands — concretions growing and acquiring gradually methods, media, techniques, becoming disciplines of soul, vital capacities — Tom Weatherly is of the process. Natural Process (Hill and Wang), an anthology that Weatherly coedited with Ted Wilentz, contains a biopsy from the corpus, in which Weatherly makes available and elaborates upon the blend of designs, patterns, and types in the bloodline. He writes: “The Afro-American poets who would correspond to the major Euro-American in this country were to be found on ‘race records,’ and put into that special category of blues. … Most of the black poets that the American white critic accepts are imitations of white writers, and the poets in the Afro-American tradition are simply ignored or put into a special ‘race’ category. While the house-niggers have been getting all of the attention … there are the poets like Willie Dixon, Peachtree Payne, Chuck Berry, Bessie Smith, and Lightnin’ Hopkins, who have gotten the shaft.” The most eloquent statement about this tradition is disclosed by his own poetry. For example, from “mud water shango”:

daddys a river & my mamas shore is black,

daddys a river mamas shore is black.

flood coming mama you cant keep it back.

lightning in my eyes mama thunder in your soul.

theres lightning in my eyes mama thunder in your soul.

i’m a river hip daddy mama dig a muddy hole.

This, and Weatherly’s “blues for frank wooten,” appeared not only in Natural Process but also in Maumau American Cantos (Corinth), his first book. Corinth Books published the first books of LeRoi Jones, Al Young, and Jay Wright as well, making itself the heavy-duty beast of the white man’s burden, shouldering it with style, and Weatherly manifested, grasped by hand more of his roots, was radical in having them, and began to milk them dry:

love is all right, but shit

loaded for bare

necessities “ive done more

for you baby

than yr daddys ever done”

walk on the tops of my shoes.

you hump like a horn

thru traffic.

“done more for you baby

than yr daddys ever done.” (“titty blown blue”)

In general, black poetry of our moment arises less from earlier black poetry or contemporary white poetry than from rhythm and blues, rock and roll, media masscult, and politics. The gimmickry and novelty effects of much of it come from this, not Charles Olson. Weatherly came from the South and “rantd in the saint marks poetry project” with David Henderson et al. so that the influence of delta, Texas, and city blues arose strongly along with that of Ezra Pound, H.D., Olson, Denise Levertov, Robert Creeley, Gregory Corso, Joel Oppenheimer, LeRoi Jones, and John Wieners. The boldness, thoroughness, and originality of his mind, his intense humanity, his profound sympathy with his subjects, and the power of his imagination operated in a questioning of truths and values in pursuit of a more appreciative and critical redefinition of the human condition as determined by the black experience, in the great modernist tradition, but closely related to black nationalist writers like Don L. Lee because the same basic black experience underlies the work of both. I.e., the same rhythms of jazz and rhythm and blues, the same schools, churches, laundromats, record stores, home-cooking takeout joints, barbershops, the same Saturday afternoon movies, and so on. His blackness places him in another world, and Weatherly sees this all too well to close his eyes to it. Yet he is a far more talented and accomplished poet than Lee, and shuns the conventional, conformist utterances that have become the standard themes of official black nationalist poetry (the greatness of black people, the tenderness and affection they inspire, the horror of white American decadence, and so on and so on). Weatherly was born and raised in Scottsboro, Alabama, a town better known for its nineteen-year rape proceedings against nine black boys, but there is understanding and compassion in this early poem:

the tennessee valley is full

of swimming holes dammed for commerce.

catfish swim, creaking in detergents.

bastards of the swan/cranes in

urgent circles follow common

low to suds, where no fish splash.

tva built offices where grass was.

dead pond’s beauty screams in the churn

of the bitter turbines whining:

tv’s summer reruns are spun-

out backwaters. fishpoles are totem,

ten pound test weight lines hang slack. (“southern accent” II)

These feelings affect the poems in Weatherly’s second book, too: Thumbprint (Telegraph). Half the length of his first, it contains twice the humor and raucous energy of its predecessor. Unlike the poetry of Jones, Lee, and the Last Poets, his work is not collective, of the people, by the people, and for the people — it doesn’t have that fervor of commitment that sends feeling boiling over form, vaporizing it regardless of genre, to leave a residue of black nationalist impulse, sensitivity, and creativity. But neither is it infected with the contagion of bad blind revolutionary faith, virulent anti-Semitic and antihomosexual sentiments that mar and trouble the writing of most black nationalists, the bitterly hostile, antagonistic views that destroy reason and succor sentimental, melodramatic social satire, shading off into self-pity and mysticism or mystique. Weatherly perceives and exercises more restraint for greater expressive effect:

this ol colored boy sorta ambles

up to bill golson’s meat market

looks in, push th door open. ‘missah

bill i wants 3 of dem

stuffd

pig

feets.’ ‘OKAY LUKE.’

(i’ll fool this boy good & stuff ’em wif shit)

& he laughs til his neck turn red.

bill puttin’ way stock for th day

up come luke grin from ear to ear

‘missah bill I wants 3 mo dem pig feets

i get this moanin’ for ol massa killibrews widder.’ (“three stuffd pig feets”)

Only a little more and the poem would have been a travesty. What in so many Southern novels becomes grotesque balances here with stability and weight, without the cloying nostalgia of, say, Nikki Giovanni’s “Knoxville, Tennessee,” or the revolutionary simple-mindedness of various corny black nationalist homecomings, e.g., Lee’s “Big Momma”). The black experience has always been communal and familial, but it has never been simply so, and the human complexities suggested in Weatherly’s poems are truer to life in its natural density than any simple and single voice could be. As the words of the blues bobbed in and out of great shrieks and growls and the melody of the guitar, so, in the family or community, black voices weaved through other voices, other rooms. The Southern environment stressed a spirit of sharing and free exchange of feelings and ideas, fragmented by the give and take of conversation, snatches of language, and bursting rhythmic exclamations, clouds of speech thundering with flashes of lightning streaming out of them. The tribal spirit of the South that black nationalists want to recapture in the North emphasized feelings we share as human beings. Abstractions like “junkie,” “dyke,” &c floundered while concrete and relevant details got funded into a larger perception or system of perceptions in the community or work of art.

a dyke can’t

hold back th sea

boyish finger stuck in

or boy’s will, it’s her flesh

she can’t hold back

loony tune. (“for billie”)

Weatherly’s use of “dyke” hurts because it’s idiomatic and not simply abusive. The pun fortifies the first impression, a difficult tonality that is sustained throughout. “to john weiners” is similar. No constant routines, measures; each poem suggests its own form à la Olson. “what is heart / is untransplantable,” wrote Weatherly. Black writing has just become likeable, and is now the most liked of many elements in the affective sequences of some critics, but Weatherly breaks the habits most black poets pattern their designs from and so is seldom appreciated. The directness, intensity, and purity of his most congested poems demand a psychological joining of emotions that is not easy: vivid perceptions. Often the object is clearly sexual, and when it isn’t it’s understood sexually, but the transfer to words diffuses the impulse into language equally vivid, difficult:

bird leg nora

a mo bile bama

high strut heels about

wif her pig fat ass (“speculum oris”)

The syllables, the music of the words themselves, their sound effects, and/or the music caused by the juxtaposition of word and word, line and line:

you thot who was that tall dark handsome stranger.

hmmmmmm

bullshitter.

hey that not a street light thats th moon. (“crazy what she calls”)

Both examples function in the context of Weatherly’s fundamentally fucked-up conception of the man-woman relationship, but the lyricism of them is more effective. Vocabulary and syntax bring subtle and complex rhythms and rimes into play to accentuate the sensuous aspects of the poem- “no ideas but in things”: not a thesis so much as a way to keep language in a state of crisis, a turning point, versus, “a turning of the plow” so speech can be vulnerable and honest. A pure lyric like “peanut butter fly” reveals the total effect that belies its apparent simplicity and best defines its nature:

let me see you boogie

woogie i know shit-

mongers who survived

‘cherry pink &

apple blossom white’

peanut butter cunts

wif sapphire blood

nappy mouf blue eyed

boogien cold turkey.

Frequently, Weatherly makes the “content” so kinetic (as in “a mo bile bama”: Mobile, Alabama, and a quick moving but ugly woman both have image in one line at once) that the curve is all there is to cling to, a fast one that Weatherly pulls off by double-crossing his words, making swift song out of awkward speech, moving by association. His energy forces all kinds of movement:

flimFlamm, your old lady is creep

she is th odour of cliche

& if th speech figures iknow

were able to sketch her gravel

gertie voice face like grendel’s dam

mitts wid asbestos skin & flint

fingernails still, i couldn’t

sit still while she slimes

‘cross this room like all

mistakes thrown up & back

out galactic gene pool

created by god fool. but she

has heart: fools gold

encased in concrete. drop it

in the ocean (“no new images”)

Weatherly plays this by ear, negating laws of form, logic, ideology, syntax, rhythm, and staying lyrical all the same. Leaping from declarative to conditional and back again, to the imperative at the end, Weatherly steams down, following old savagy and wild roads into himself. The question that Jones asked was “HOW YOU SOUND??” and Weatherly seems to agree: the poem has a harsh lyrical determination like a barroom brawl or “the dozens” or some more hot air from Harlem. Black literature has been heretofore too polite to allow anything this loud and wrong and raunchy, though it is this free-ranging speechlike disorder that permits the intensity and order that he finds for it to move. Almost every word has secondary tones which form a component of its meaning, though they are not heard distinctly: “flimFlamm” is, at best, only a name as Mrs. Malaprop is; “creep” is a verb as well as a noun (creeping odors, sliming); “figures” of speech could be outlines of the woman as a “sketch” is; “flint,” a rock as “gravel” is, makes the spark “asbestos” puts out. But “flint” is also part of “skinflint”; “asbestos” is a character from the comic strips as “gravel gertie” is, and “he’s black” has the mark of Cain, as “grendel’s dam” does. She has a heart of fool’s gold that gets her slain by Beowulf; liquids: the ocean, vomit, slime … and so on. The range of harmonics is massive; still the poem is short, crafty, shrewd. Weatherly’s power and speed are comparable only to black musicians like John Coltrane, Ornette Coleman, and Cecil Taylor with their funkier wilder blues. Aside from occasional passages in Ishmael Reed’s novels, nothing is like it in black literature. The night and dark of things, the man/woman, hard/soft, heavy/light, rising/falling, black/white symmetries, the “moonseed” that combines high and low, connects them like a synapse, come together in contrast, gradation, theme and variation, almost overemphatically, but in the spirit of the blues, ironic in that sense. Weatherly’s sophistication and culture, what is most modern in his work, flows without detour into what is oldest. His life, experiences, flow into what is public, general. Weatherly sings the body electric. His poems are physical actions, the voice of one crying in the wilderness, a distant voice in the darkness, uttering.

Edited by David Grundy