Let 'em eat kitsch

A review of Thomas Fink's 'Joyride'

Joyride

Joyride

Ceci n’est pas un article à propos de schtick (except perhaps as René Magritte might have it be). Thomas Fink’s glorious new book of poems presents us often with the joy of Yinglish, but in whole it is all about the magical present, and this is no coincidence. Is it inspired schtick — Yiddishkeit’s bestowal upon us all — or might we simply take his new volume as especially inspired high comedy, which approves of serendipity? I don’t think so, not that Fink doesn’t possess a joltingly wicked sense of humor (also to be found in his earlier books, yet with even more verve here in Joyride). I grant that Yinglish Strophes, a series of poems extending across a number of collections of Fink’s verse, might be read as schtick by casual readers. He includes a number of new “strophes” of this kind in Joyride.

Here are a few lines from one of them, which will be weirdly familiar to some of us from our youths, I suspect, who retain memories of some alter cocker holding forth: “I fell again and // again I fell. More the / reading I keep, the / more examples of serious is finded.” A more poignant poem in this series begins (its first line here does not cue us as to what’s to come), “How long been here // this place? Died well, / died good from that / hospital mother. That // was a day and a half yesterday.”

Fink does savor the delicious wrenchings of American syntax and pronunciation by people such as his own Eastern European Jewish ancestors. And how not? A New York Jew (Alfred Kazin’s masterful memoir of this name helps us to navigate Fink’s warp-speed lines, yet only up to a point), Fink has inherited the jouissance of both the written and oral discourse of his world. This world is a great deal wider and more complex than that of his Jewish upbringing, however. So it is lucky for us that he has provided this guidebook in which neither Kazin nor Leo Rosten (nor the two together) could account for the soaring flights of language in its purest, indeed subliminal, form, arranged in Joyride into a number of ongoing series. Aside from Yinglish Strophes, there are new entries from Dusk Bowl Intimacies, Jigsaw Hubbub, Hay(na)ku Exfoliation, Goad, and Home Cooked Diamond; and Fink has interspersed a number of freestanding lyrics among these sequences.

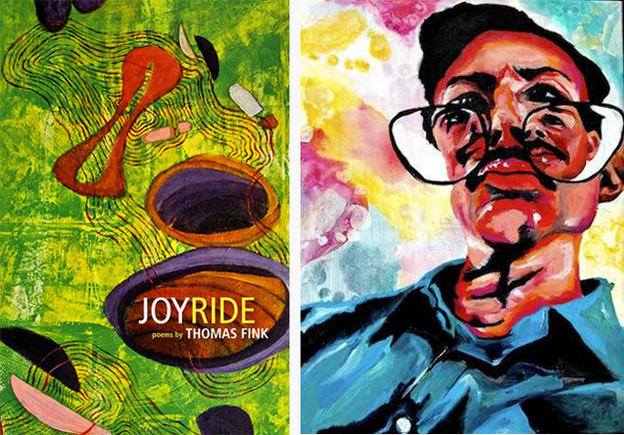

But if you try to grasp the poems by attending to their gorgeous exteriors you’ll have fallen into a trap — not one set by Fink but rather simply the trap of language. An overly liberal reading of his painting reproduced on the front cover of this joyous new book is that we can see the various shapes, forms, waves, and/or occurrences of the biological or simply the material world, which are held within their asymmetrical orders by some deeper order of the sort that would have allowed Einstein in his later years a good night’s sleep. Make no mistake about it: Fink’s world is not one in disarray. Fink is a master at working within constraints that make themselves disappear and then, just when they do, appear again. (Mazel Tov!)

There are the explicit constraints, such as we see in his series of poems whose respective forms are governed by rules. For instance, the poems in the Dusk Bowl Intimacies section of the book consist of a paragraph each and then, reminiscent to me of the bob-and-wheel structure in Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, a subsequent set of short verse lines, the number of which match the number of sentences in the paragraph above them. These short lines are arranged according to a form developed by the poet Eileen Tabios, which she calls the “hay(na)ku,” her form adapted from the haiku. (Caveat lector: there’s a lot more to all this than what I’m saying here, so you may wish to get in touch with her, or with Fink — or maybe check out this website by J. Zimmerman.)

Whatever the constraint or form, the poems in Joyride showcase the canny hearing of which Fink is capable and reveal what I’ll call his etymological desire — which, given his penchant for the pun and within the happenstance of any given moment, results in strange, often funny, and beautiful (mis)statements. Reading these, one may be led to wonder at the ultimate constraint: natural, historically evolved language (rather than, for instance, an artificial language such as in mathematics). Like the alluringly odd shapes and brash colors in his painting, Fink luxuriates in both the debris and the founding elements of expression. (A computer scientist I know works on the ninety-eight percent of genetic material that he once called “garbage” — evolution’s or nature’s mistakes? — although recently we may be seeing that some use is to be made of that portion of the spectrum.)

Either way, Fink knows language from the inside out — rather different from a poet who is seduced by language’s shimmering surfaces. And here’s another thing: While we are language beings — i.e., humans and uniquely so — we are also cultural beings (the two one, of course). So a phrase like “Stronger than dearth” (in “Jigsaw Hubbub 10”) can mean “stronger than death” as in the avenging angel or Jesus Christ Superstar, or “stronger than dirt” as in Mr. Clean.

Now, would someone please tell me which signification takes precedence here (from “Goad 20”):

Your mother is very loud — of you: “He’s been banged

from Bahrain to Brisbane, Sweetie.” For you, schmuck,

conversation’s been a trans

ition between climaxes. Vol

ubly laconic & transactional,

except when you know it’ll

except when you know it’ll

tag you as cal ous galoot.

Fink not only loves the detritus of culture; he bathes in it, singing in his tub the comic-book aphorisms of daily life. His antennae take in the memes and the castoffs — maybe better to say they suck everything in — and then the machine of constraint misreads the culture in surprising and illuminating ways, ways in which we all speak; and what we hear ourselves say must be what we’d encounter if we had just come out of general anesthesia, though we’ve not yet retrieved our presumptions about the world through which we process what we see and hear. Thus we get, for example, “Hay(na)ku Exfoliation 15,” in which a “red sign / keeps beasts, / even pensive ones, / out of the / circulation area […].”

“It’s amazing that you found me here of all unknown places,” Fink exclaims (in “Dusk Bowl Intimacies 27”). “Sometimes,” he continues, “love does its homework diligently. Can you fill that void with bonds? Heat of the random crystallized.” Here’s one more, from “Home Cooked Diamond 3”:

Brood

brooding. I

seek worries,

monitor ing every

one. Stoned on crisis.

“So — I love you; do

you have my cat?” You

should stop tolerating.

Let ‘em eat kitsch.

The joyride Fink takes us on is the exhilarating surfing of the nonlinear waves of the moment-to-moment we ought to pause, once in a while, to marvel at. Joyride is not pure joy, however. In any case it’s not kitsch, or cheap thrills, and rather gives fleeting, possibly chimerical glimpses of language's dark matter. I think this book is the milestone marking the full attainment of the poetics Fink has been developing for years. The poems are brilliant and masterful in their execution.