Weatherly's words

A tribute to Tom Weatherly

Editorial note: Rosanne Wasserman’s tribute to Tom Weatherly was originally published at the blog for The Best American Poetry on August 4, 2014, and is reproduced here in slightly edited form.

— Julia Bloch

Some time around July 15, we lost Tom Weatherly; his heart gave out. His fiancée, Linda Murphy, hadn’t heard from him in a few days; no one had — where were all his phone calls, emails, posts? People heard from Weatherly. But he was gone, alone, in the big house he’d inherited from his mother near his birthplace of Scottsboro, Alabama. But we’d just heard from him the week before! He’d called and talked to our daughter twice. He’d talked to so many people. We have emails from him that we were about to reply to. He’d just sent me a link to a song, “Mother May I,” in a note saying, “A ringtone for Zancy lady.”

He read the Hebrew name of G-d, the tetragrammaton’s four unpronounceable letters, as a representation of respiration: one breath in, one breath out. That sound was the Holy of Holies. He told me this last summer, over the phone. I was sixty years old, but that insight sounded like the most brilliant thing I’d ever heard. He took very seriously his midlife conversion to Orthodox Judaism, talking to rabbis and Hasids, reading Maimonides and Hillel, and using his middle name, “Elias,” to sign himself at times. Eclectic defined him, as did sudden turns at perpendicular angles. He called himself “the grandson of Wallace Stevens and Hilda Doolittle, Jimmy Rogers and Sippie Wallace, and first cousin to Paul Blackburn” in a questionnaire on his New York School connections. Sippie Wallace, a jazz singer and songwriter, was called “The Texas Nightingale,” and Jimmy Rogers played with Muddy Waters. Blurbs from the back of Weatherly’s last book, short history of the saxophone, praise how his work “condenses the wisdom of a life and vast readings into brilliantly compact music,” as Andrei Codrescu writes; Howard Kissel of the New York Daily News calls him “that rarest of birds, a mystic with a sense of humor … a red-blooded American Zen master.”

Weatherly’s family made him proud. His father was a chemist, mathematician, and school administrator; his mother taught school. His daughter Regina’s twin girls were a delight for him; he was always a man good with children, the caregiver for his own son, nicknamed T3, through his infancy and childhood. He told me he’d carried that baby around wherever he went. He went to college early, attending Morehouse at age fifteen, in 1958, but Alabama A&M College expelled him for publishing an underground paper, The Saint: years later, he’d sign himself sometimes “W” with a halo like the one used by pulp detective Simon Templar, and he kept a blog called Saint Satin Stain. After college, he joined the Marines and was, as he told my daughter just recently during a phone call, at the Bay of Pigs invasion in 1961. But he kept on with that education: in New York by the mid-sixties, he became a regular at St. Marks Poetry Project, studying there with Joel Oppenheimer in 1967, then teaching workshops himself. He attended City College one summer and Hofstra University for three sessions, and in 1974 joined David Ignatow’s seminar as a special student at Columbia University, which is where Eugene Richie and I met him.

In the mid-sixties, Weatherly met members of Umbra, a Black poets’ workshop active from 1961 to 1964 on the Lower East Side. Eli and Ted Wilentz of the Eighth Street Bookstore published Weatherly’s first book, Maumau American Cantos (New York: Corinth Books, 1970). Tom, in turn, gathered work by many Umbra poets in Natural Process: An Anthology of New Black Poetry, which he edited with Ted Wilentz (New York: Hill and Wang, 1970). The group celebrated a fiftieth reunion last autumn, which Tom attended. He began the Natural Process Workshop in East Harlem in 1968; in the early seventies, it merged with the Saint Mark’s Poetry Project. In addition to his workshops at Saint Marks, he taught Afro-Hispanic art at Rutgers–Newark and poetry workshops at Rutgers, Bishop College, Grand Valley State College, and Morgan State College. He taught for Poets in the Schools in New York and at Rikers Island. Later, he tutored privately, working with poets Madeline Tiger, Julia Kasdorf, Megan Buckley, and others. He was a natural teacher, generous and engaged, pulling books from shelves, introducing writers to masters of their craft both old and contemporary. For my own work, Tom’s opinion of a poem was one I trusted above all others: he knew the music.

At the Lion’s Head Pub, where he was the second cook, he met more writers, artists, and musicians, including David Amram and the folk singer Dave von Ronk. Codrescu remembers him as one of a conterie of macho writers, “growly-lion types,” “a tall Black poet” who “always gave poor writers like myself extra shrimps in the shrimp cocktail, which was the only thing I could afford besides one beer.” The afternoon that Codrescu first met George Plimpton, a story that he relates in a 2003 Downtown Express article, Tom gave him whiskey on credit at the bar.

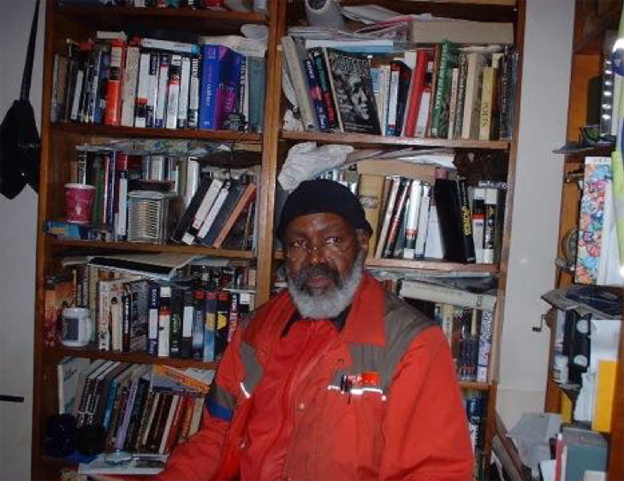

After the Lion’s Head closed, and for the next thirty years, you could find Tom at the Strand Bookstore. His book collection burgeoned: he’d show me rare editions of H.D., whose work he adored and introduced me to. For a lover of books, this job was almost too much: when we lived near him on the Lower East Side, his East Houston Street apartment, at Hamilton Fish Court, had been outfitted with metal bookshelves arranged like library stacks, with narrow aisles of living space between them. He worked at the Strand Bookstore with poet Ben McFall, the artist Aissatou Mijiza-Weaver, and others, and met many more friends and writers while there. Michal Hollander tells me that in 1981, during her first month at NYU grad school, he found her browsing the stacks, reshelving misplaced books as she went along. He decided then and there that he loved her. In the next millennium, his mother left him a red brick house on a leafy street in Huntsville, Alabama, and he relocated, splitting his time for a while between his hometown and the city where so many of us awaited his migratory returns.

Back in the early ’80s, when Eugene and I were at NYU’s Silver Towers between Bleecker and Houston, Tom was way down east by Hamilton Fish, in an apartment with two bicycles hanging from bike hooks in the ceiling, bookshelf stacks marching through the entire studio room, and a couch by the front windows. He was a bicycle evangelist who could talk anyone into buying one. Once upon a time, he accompanied me to an Alphabet City shop where he knew the staff well and outfitted a mixte frame for me, with side panniers and a wide seat. Then we went riding out very early in a summer’s morning, all the way west down Houston and out to the Hudson River docks. On the way back, he bought a watermelon from a street vendor and bungee-cord-strapped it onto the front rack of his bike, and we took it home to Gene for breakfast. Ten years later, he rode his bike through Long Island, camping out in our backyard in Port Washington overnight.

Enamored of and soon an expert at internet communications technology, Weatherly kept more than one blog: he started Eclectic Git and Saint Satin Stain. He sent his “Weatherly Report” periodically to a long email list of friends and followers, and posted often on Facebook. He also wrote for and posted on the progressive blog Left in Alabama, a sounding board for his changing politics. Well to the right, for much of his life, of most of his New York cohorts and associates, a lifelong Republican and Libertarian, Tom swung to the left during the Bush administration and supported Barack Obama enthusiastically.

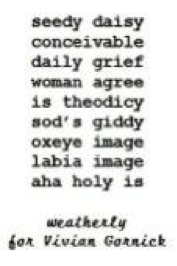

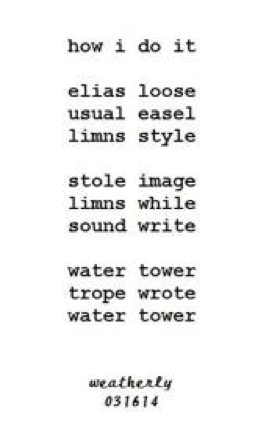

New York poets whom he lists as influences (on a questionnaire that he sent me in 2006) include Oppenheimer, Sam Abrams, and Ignatow, as well as learning “many esoteric bits” from Saint Marks poets Jerrold Greenberg, Michael Stephens, Marcel Flamm, Ronald Edson, and Ted Berrigan, as well as Anselm Hollo, Codrescu, Anne Waldman’s book Giant Night, and the African American poet Samuel W. Allen (Paul Vesey). He also lists Esther Levenberg and Alma, and it’s too late now for me to ask him whom he meant. Two other collections appeared in the early seventies in addition to Maumau American Cantos: Thumbprint and Climate. (Eclipse has Thumbprint and Maumau American Cantos to download or view.) In the thirty years until his next book, while his themes were always flesh and spirit, gender and racial conflict, science, history, and politics, Weatherly honed his language to an exquisite degree. He invented an innovative syllabic form that he called the glory, which rivals the sonic patterns of Chinese poetry. He would work up different glory patterns, including an “X-glory.” The poem “musick,” below, from short history of the saxophone, is a double glory:

bluesy subtle bluest

thence beauty blooms

sunlit bluets center

whence brutal musics

humans vent as blues

Michal Hollander describes how he would graph these poems out on a vertical grid of sound and letters, working the vowels and consonants until a new word appeared and took its place. He was committed to the Courier New typewriter-analog font so he could do this tricky gridwork. And he liked to play with synesthesia, coloring in the sounds of the beats or the vowels:

/u/u

u/uu

/u/

/uu/

/u/u/

//u

///u

/uu/u

u//u/

He decorated his dictionary; I have been talking about his dictionary to poets and artist friends for the last thirty-five years.

He wrote this description of one double glory, which serves as a kind of chorus to “Wally,” a long poem in short history of the saxophone. The blues-style stanza follows, with a sonic rewriting:

an improvisation on the blues line “never muted heart,” the preamble to “wally,” an improvisation in several sections dedicated to Wallace Stevens and with allusions from The Man with the Blue Guitar, with influences of rhythm and blues, jazz, and vocalese (respect to Eddie Jefferson, Betty Carter, King Pleasure, Dave Lambert, Jon Hendricks, Annie Ross, also Manhattan Transfer).

never muted heart

never muted heart

eclectic blues guitar

něv ər my tĭd härt

něv ər my tĭd härt

ĭ klěk tĭk blz gĭ tär

A blog post titled “Some Music please,” from Saint Satin Stain in 2010, records a bit of the kind of craft advice so many of us came to him to hear:

Forget what you were taught about poem making in grade school, middle school, high school, undergrad, and grad school, unless you had a teacher who actually knew that it is a craft.

[…]

You have heard teachers say poetry and prose. They put a genre with a mode because of their profound ignorance.

There are two modes in which you can write, prose and verse. Prose is unmetered and verse is metered.

[…]

The genres are novel, play, essay, and poem. Poem is different in that music is the important focus not the tell a good story of novel, dramatize a good story as in play, or explaining or describing as in essay. Although a poem may do some or all of these, its focus is playing music.

Is it possible that his focus on music in verse, his innovative brilliance with form, has kept him from wider recognition? Aldon Lynn Neilsen writes, in Black Chant: Languages of African-American Postmodernism, that often Black poets working outside mainstream traditions have been ignored because of how they write. He’s surprised that a poet as remarkable and influential as Weatherly hasn’t received wider critical attention. Burt Kimmelman wonders, in a Rain Taxi article, why he is missing from Out of This World, a 1991 Saint Marks anthology. But those in the know knew. Tom’s name appears dead center, on page 23, number 60, in a list of one hundred and eight notable writers, in The Vermont Notebook, John Ashbery and Joe Brainard’s collaboration from Black Sparrow Press in 1975, along with the usual New York School suspects and several others whom you wouldn’t necessarily expect, including Bob Dylan.

All this week, Frank O’Hara’s epitaph has rung in my ears for Tom Weatherly: “Grace to be born, and to live as variously as possible.” And what would Tom say about himself now? He’d been meditating on the event; in a post on Saint Satin Stain:

If dead is non existence

If dead is non existence, then we were dead twice: once before conception;

once after we die.

Enjoy this short time; it’s fun, even the bad times are fun.

And a last word, on poetry, from a master craftsman:

Edited by David Grundy