'never muted heart'

Tom Weatherly's trespass

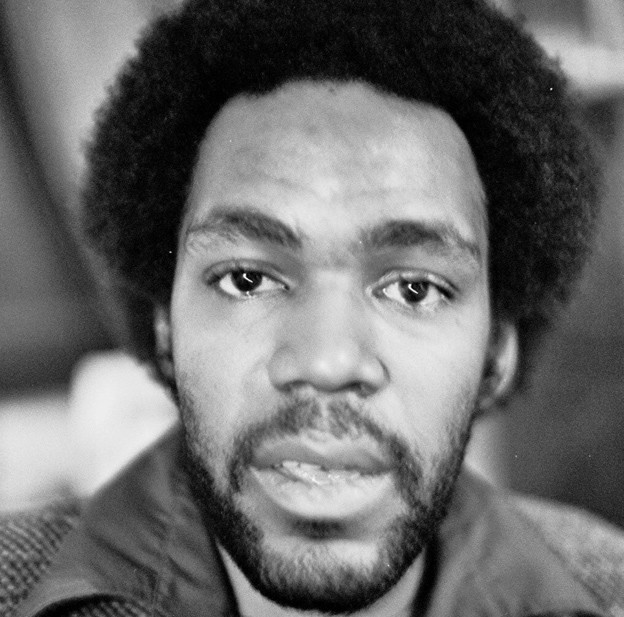

Maumau American Cantos, Tom Weatherly’s first collection of poetry, possesses one of the best titles for a book of any decade of the twentieth century, and perhaps even for the century as a whole. Yet, three years after his death, his work remains almost completely ignored. In this essay, primarily via readings of poems from the Maumau Cantos, I will hope to show why such neglect is borderline criminal.[1]

Weatherly’s poetry is seriously playful and expansively compacted, shot through with quickfire flashes of anger, love, tenderness, and a biting wit. He had a rare gift for transmuting the techniques and spirit of the blues into literary form. There is — almost — nothing else quite like it, though it is work steeped in copious practices of reading, listening, observing, speaking, and singing. Weatherly combines allusions to sources as diverse as English Renaissance poetry, the white modernist canon, African American music, the sexual slang of the dozens, and to his own friends, lovers, family, and influences. Though his poems are often short, they are densely packed with the near-metaphysical imaginative stretches to be found in the everyday rituals of street speech, verbal games and jousts, toasts, rhymes, and song lyrics. Weatherly blends disparate contextual allusions both to show similarities and to bend them away from themselves, at a vector from canonical literary and white supremacist mainstreams. Riffing simultaneously on the lute songs of Thomas Campion and the blues songs of Blind Lemon Jefferson, on Pound, Jimmy Rogers, and H.D., Weatherly, in Aldon Nielsen’s words, “bend[s] our language as a blues musician bends our notes,” his poetry manifesting “a compositional motion […] whereby sound and association pull poet and reader from one word to the next, as though content were truly extending itself as form.”[2] Throughout, he draws on the resistant strengths of vernacular and oral traditions too often demeaned as “folk idiom” while also extending and going beyond them, to sing his own blues song.

The second of the Maumau Cantos, a tribute to John Coltrane entitled “yellow brick road,” opens with the line “we trespass the blues.”[3] I think this can be taken as something of a creed for Weatherly’s work as a whole. Though he is one of the finest blues poets of the second half of the twentieth century, Weatherly’s poems are not bound to a mere imitation of blues form. Trespass is a useful way to figure the territory that Weatherly’s poetry stakes out: the migration from South to North, from Alabama, where he was born and where he died, to New York, where his poetic career flourished; from the rural to the urban; from the sexual to the political (and vice versa); from the modernism of African American tradition to the traditions of European modernism. Through all of this, Weatherly almost never fits easily into the poetic schools that scholars (and poets) like to set up around writers, permanently trespassing the fences they erect. As he writes in his preface to the anthology Natural Process: “Yeh yeh […] I know, but we don’t live in the same medium.”

In his essay for this feature, Weatherly’s friend Burt Kimmelman notes that Weatherly sought “to make a poem in its entirety that has the unitary force of some ur-word.” This is serious business, and uniquely places Weatherly between the parings down of anything from Imagism to minimalist poetry, and the fundamental rootedness of the black radical tradition in a language of substitution, puns, and playful open disguise. Weatherly shows us how the blues, as Houston Baker has convincingly argued, was always already modernist or avant-garde, and how, conversely, much modernism was, to an acknowledged or unacknowledged extent, saturated with the blues’ cultural contributions.[4]

Thomas Elias Weatherly was born in Scottsboro, Alabama, in 1942. Eleven years previously, the town had become a focal point for left-wing activism against racial injustice after the infamous framing of the nine “Scottsboro Boys” on false charges of rape. The Scottsboro incident formed a crucial motivating factor for the work of politically committed black writers like Langston Hughes, and Weatherly recalls reading Hughes while living in Scottsboro, where Hughes’s politicized poetry competed for attention with afternoons spent watching Tarzan movies at the cinema:

(The Scottsboro buck.)

On clear Saturdays read Langston Hughes,

make my bed, off to dig on Tarzan, king of great apes,

swinging down my head at the Ritz. Langston

and Tarzan fight cold war for my soul flesh[5]

Weatherly was the son of a teacher and a school administrator. After several years of college-level study in Alabama, he was expelled from A&M University for editing and publishing The Saint, an unauthorized student magazine, and embarked on a short-lived career as a preacher in the African Methodist Episcopal (AME) church.[6] Either before or after this, he served in the US Marines.[7] Moving to New York by 1966, he lived on the streets and hitched around; associated with various poets around the Lion’s Head Pub, where he worked as the second cook, and the St Mark’s Poetry Project; studied; taught and attended workshops at colleges, universities, and prisons in New York, Newark, and Texas; and edited the important anthology of African American poetry Natural Process with Ted Wilentz. After years working at the Strand Bookstore, he moved back to Alabama on the occasion of his parents’ death, and this geographical move from the center of literary power — as well as his aversion to the “lewd renown” of personal celebrity (“I want my work famous, not my face”) — may in part account for his obscurity.

Placing Weatherly

Weatherly’s published output is small. Three pamphlets appeared during the 1970s — Maumau American Cantos (1970), Thumbprint (1971), and Climate/Stream (1972, a collaboration with Ken Bluford) — and a further book, short history of the saxophone, came out in 2006. Indeed, his editorship of Natural Process, one of a spate of anthologies of African American writing that appeared in the 1970s, may be his best-known contribution to the literary culture of the period. Weatherly knew and published alongside writers from the Umbra Poets’ Workshop, a New York–based African American poetic collective, and, like a number of the Umbra writers, his friendships with a number of white writers and poetry scenes complicates our sense of the radical black writing of the 1960s exclusively within the nationalist notion of the Black Arts popularized by LeRoi Jones/Amiri Baraka, Don L. Lee/Haki R. Madhubuti, and others.

In an essay on Weatherly printed in the first issue of Lip magazine in 1971 and reprinted as part of the present feature, Ken Bluford argues that, while Weatherly’s poetry draws its strength from many of the same sources in black vernacular culture as culturally nationalist Black Arts poets like Lee/Madhubuti, it

shuns the conventional, conformist utterances that have become the standard themes of official black nationalist poetry (the greatness of black people, the tenderness and affection they inspire, the horror of white American decadence, and so on and so on).

For Bluford, Weatherly’s poetry

doesn’t have that fervor of commitment that sends feeling boiling over form, vaporizing it regardless of genre, to leave a residue of black nationalist impulse, sensitivity, and creativity. But neither is it infected with the contagion of bad blind revolutionary faith, virulent anti-Semitic and antihomosexual sentiments that mar and trouble the writing of most black nationalists, the bitterly hostile, antagonistic views that destroy reason and succor sentimental, melodramatic social satire, shading off into self-pity and mysticism or mystique.

Emerging from a fundamentally Southern background of “schools, churches, laundromats, record stores, home-cooking takeout joints, barbershops, the same Saturday afternoon movies, and so on,” while also infused with the urban energies and in-group reference which Weatherly found in New York, the poems are punning, vulgar, obscene, satirical, and, above all, sexual. Weatherly, himself until late life a conservative Republican (“like George Schuyler,” as he put it in a 1974 interview with Victor Bockris reprinted in this feature), rejects both the left- and right-leaning varieties of black nationalism that came to be associated with the BAM while firmly (but unprogrammatically) endorsing black working-class vernacular culture and expressing sympathy with the liberation struggles waged by the likes of Malcolm X and the Kenyan Mau Mau named in the title to his first book.

In his later work, Weatherly became interested in developing a technically controlled prosody based, in part, on the blues, whose composition, as noted in Burt Kimmelman’s essay and Rosanne Wasserman’s generous and wide-ranging memoir-obituary, involved placing of letters and sound-values on various synesthetic, quasi-mathematical grids. Some of the more extreme minimal tendencies — “o p e n / p a g e / e g o s / n e s t” reads one complete poem from short history of the saxophone — recall Aram Saroyan (whose reminiscence of Weatherly appears alongside Kimmelman and Wasserman in this feature).[8] Yet however “minimal” they might appear, they are almost always prickly and idiomatically inflected. Weatherly himself puts its best: “elias built / model poems // skies unlit / hotly vocal.”[9]

For Weatherly himself, this late work reached a desired balance between the fierce energies of the earlier work and the formal concision he had spent years developing. He once claimed that his two best books were “short history of the saxophone and Thumbprint, in that order,” and in a comment on Maumau American Cantos, published on the Goodreads website, he writes, “there are serious problems with a few of the poems; I have rewritten some of them, but it’s a good start on lingo music.”[10] “Lingo” here implies in-group, underground language use, the transformations wrought on speech by music, and the filtering of both through the specific rhythms of poetry itself. Both Weatherly’s later and his earlier work are very much concerned with the blues (understood in a Dionysiac lineage that sees it figured as “goatsong”), even if he only occasionally writes poems in blues forms per se.[11] This makes sense if we understand that the blues, for all its associations with excess, is formally based on just those modes of concision that Weatherly came to value — repetitions with minor variations, double and shifting meanings that hinge on puns, changes rung across images that recur from song to song.

At the same time, Weatherly’s poetry enacts a distinctly personal style, vernacular and direct but also somehow private and secretive. Despite its tendency to bald statement — what Weatherly later called “artsy belly tunes” — one sometimes senses that certain stages in the process of composition have been elided, so that the poem’s frame of reference is partially hidden from view. For M. G. Stephens, Weatherly’s “private shorthand” — “abbreviations, jargon, private puns” — can sometimes “defeat the emotions he wishes to portray.” It’s worth probing this further. Weatherly’s work can be placed not only alongside the Black Arts Movement, but alongside the New York School poets, many of whom, indeed, were his friends. As Lytle Shaw has argued, in the work of the New York School, abbreviations, puns, and references to friends and lovers form a coterie poetics which acts as one way to swing away from the normative center. Groups who feel themselves to be already “authentically” marginalized self-consciously take on that marginalization as a form of perverse power, self-defense, and mutual, collective support.[12] Weatherly insists on dialoguing with the canon — Maumau American Cantos references everyone from Thomas Campion to Samuel Taylor Coleridge to Ezra Pound — but his poetry also serves as an intense communication to and between those friends, through notes, poems, and social gatherings, which may or may not end up being written into broader historical canons. Suggestive in this regard is Weatherly’s publication of poems in the Detroit-based little magazine Free Poems Among Friends. “Free” here suggests a practice of gift-giving which establishes a reciprocal economy of in-group relations based on bonds of friendship that supplement or replace those of conventional domestic or capitalist models.

As Shaw notes of Frank O’Hara’s work, artistic predecessors and the “queer family” of friends, lovers, and acquaintances form a replacement family which sustains and is sustained by the very grain of his poetry. Likewise, while emphasizing the familial traditions of which he partakes (“thomas son of thomas”), Weatherly also insists on new ties which both build on and go against the old: as the poem “southern accent” puts it, “following dogtrot after father,” yet “questioning his myths.”[13] Hence, the African Methodist Episcopal tradition — where he had briefly followed the ministry in the same Scottsboro church as his “great granddad” — is supplemented or replaced by Judaism, the church by radical politics, and college by a tradition of literary subversion and defiance: Weatherly was suspended at an early age for distributing a newsletter entitled The Saint. Weatherly (re-) names himself constantly, playing between the givens of family tradition (Tom Weatherly, Thomas Elias Weatherly Jr.), the renamings of newly adopted religious identity (Thomas Eliyahu ben Avraham), and the playful nicknames by which he figures himself as “tomcat,” “wooten,” and the like. Through such shifting nomenclature, Weatherly takes on the names which have defined him before he was capable of self-definition and makes them a part of an identity by which he might constantly define and redefine himself. In doing so, he places himself within the various African religious traditions which inform their Afro-Christian descendants and more secularized musical forms, from voodoo to hoodoo to spirituals to blues. In this living tradition, ancestral forces and figures are sources of power, reminders of traditions of collective resistance, names to conjure with and to be sustained by.[14]

Whether naming others or himself, Weatherly is hard to pin down. His work operates between Black Arts Movement and New York School, modernism and the vernacular, music and speech, a group “inside” and an “outside.” However useful it might be to think of his work in relation to the poetics of coterie, Weatherly doesn’t quite offer himself up in the way that a poet like Frank O’Hara does. Neither does he seek out the very different kind of collective envisaged in the Black Arts project to form a new form of racialized subjecthood. If the New York School (and, to a lesser extent, the Black Arts) arguably moved from “margin” to “center” over time, Weatherly remained firmly within the spirit of the margin. We see this aspect in his playful preface to Natural Process, in which he insistently refuses any kind of tokenistic adoption whereby the market value of African American art soars while most of its practitioners continue to languish in obscurity. Always active and open to poetry as a socialized activity, whether in his literary friendships, the poems he sent to friends, or the workshops he ran with students and in prisons, Weatherly was also wary of the retrospective canonization represented by such forms as the anthology, one that excludes as much as it includes. Perhaps this wariness explains his relative silence from the 1970s on: a way of avoiding conscription into the kind of writing of literary history that starts to form some sort of new center, to swing the gravitational pull.[15]

“walk down fifth avenue, hawkbill / in my hand”

That gravitational pull is most obviously inflected by the complex negotiations between Northern and Southern identity present throughout Weatherly’s work. Weatherly’s writing on the relation between South and North can be roughly divided into two often competing impulses. On the one hand, there is the urge to settle, to find house as heart as home, to “come home for good,” as “blues for franks wooten” has it. On the other, there is the sense of “trespass” invoked in his poem for John Coltrane: the desire to escape the feeling either of unwilled confinement or of a forced, unwilled movement, both accompanied by an unavoidable sense of loss. The migratory move from South to North is of necessity accompanied by a sense of absence or nostalgia which further links back to the irrecuperable loss of memory, name, and place that was the historical trauma of the Middle Passage. As Weatherly puts it in “to a woman”: “can’t say it’s not / a language that makes you / repeat its singing // for you I groan […] it is beginning / it goes down / thru centuries.”[16]

Weatherly’s refusal to sentimentalize such loss, and to tie it always to the question of community in particularity, rather than abstraction, is key. In Ken Bluford’s account, what Weatherly does that many Black Arts writers could not is to transplant a communal Southern experience to the urban North while avoiding twin traps: reducing this experience to a sentimental, nostalgic memory, or appropriating that experience for a political program which glosses over its original details, points of reference, and idiomatic usages. By contrast, Weatherly could retain the fluidity of vernacular Southern discourse — at once abstract and filled with a particularity of reference — without subordinating it to a political program. This is not to say that politics is absent from this work, and his use of such language was certainly inflected by Weatherly’s own lived experience, an experience crucial to understand if we are to seriously grapple with his poetry.

Maumau American Cantos’s opening “autobiography” notes Weatherly’s migratory rebellion or “division” from the vision of the Southern church.

had a vision

entered a.m.e. ministry

assistant pastor of saint pauls scottsboro […]

had a division: left god mother hooded youth &

the country for new york, lived on streets,

parks, hitchd the states.[17]

Weatherly’s individual trajectory fits into wider patterns of racial-economic migration. Such movement is also tinted with the outlaw-wanderer myth on which Weatherly draws in a synthesis of Homer and the African American blues musician: “these are like Homer’s blues / themes,” as he memorably puts it.[18] This myth exists as a poetic counter to the drudgery and toil of repetitive exploited manual labor, the threat of racial violence, and geographical limitation.

Given this, throughout the texts from the Maumau Cantos in particular, the figuration of the blunt but coded and rich allusions of blues tradition, gris-gris and the like always retains a raw, rural, Southern flavor, however ostensibly New York–based the immediate location. The third canto of the sequence which gives the overall volume its name — “the issue, the blood, is heavy” — provides a good example. It is also arguably the most directly political of all the poems here. The poem begins as a letter to Weatherly’s parents with a classic case of New York migrant blues, the poet under attack from unnamed assailants.

dearest big tom & lucy belle

they mebbe come suck

at me the fan, & fuck up the current

modern jawless vertebrates

lampreys

new york citys dont hold their

mouf right[19]

This variant on the bloodsuckers theme is clarified by references to political figures: “anthony travia / or the estonian minister of cultural affairs to the U.N.” Travia, a Democrat elected by Lyndon B. Johnson as the New York Assembly Speaker, had undertaken a bipartisan alliance with Republican millionaire governor Nelson Rockerfeller to promote the 1967 New York Public Employees Fair Employment Act, or Taylor Law, labeled the “Rockefeller-Travia Slave Labor Act,” or “RAT bill,” by union critics because of its prohibitions against strikes by public employees, with work stoppages made punishable with fines and jail time.[20] In Weatherly’s poem, the mention of Travia leads to a comparative reflection on an equally corrupt Southern politics, whose mores are illustrated via a reference to the tobacco-chomping Big Jim Folsom, former Alabama governor and notorious grafter, who, in what a 1997 documentary film labeled “the two faces of populism,” promoted racial integration in a way acceptable to the white middle class. Weatherly writes:

southern politics aint got

less probably mores of the region

flavor: big jim folsom

the man in bama

forkd a chaw the cracker get his

mouf around wouldnt choke.[21]

By contrast, Weatherly embraces the new urban radicalism of Malcolm X, while still acknowledging his Southern roots: “now you teachers share- / crop reared me, now the sirens / honk at my hymns to malcolm.” William Carlos Williams’s “no ideas but in things” is turned on its head, so that (Malcolm’s) “soul” is reclaimed as a “thing” which might raise consciousness and spur political action.

what the man … did to stoke

fire beneath his black

skin fuses his soul the thing, not in ideas

my poetics a sociology independent

of the results[22]

X’s defiant advocacy of armed self-defense serves as a contrast to a system rigged by “dip shit mothafuckn blood / suckers” who “stuff the ballot, drain / the treasury, increase taxes[.]” In April 1964, X famously posed a choice between “the ballot or the bullet”; here, the ballot has already been “stuffed” — in the literal sense, the placing of papers in boxes, but in the sense Weatherly means here, fixed, through political corruption.[23] Given this, the notion that democracy will bring change is seen as illusory, and, if we read “stuff the ballot” as an exclamation of annoyance rather than the action of the “blood / suckers,” the ballot itself is told to “stuff it.” In ironic reversal, the land of free democracy is characterized by bullets, the land of imperial war by ballots — “bullets in mississippi / election returns in Vietnam” — the gap not covered up by the election of a “token / NEGRO.” The link Weatherly draws here between domestic and international politics resonates still further when we consider that Malcolm X endorsed the Mau Mau uprising in British Kenya (which lends Weatherly’s book its name) and anticolonial struggles across the globe, from Algeria to Vietnam.[24]

Inspired by Malcolm X, Weatherly’s own Maumau Cantos unite song, poem, and acts of revolutionary violence in their own acts of fusion. In “imperial thumbprint,” Weatherly writes, via Nina Simone’s “Mississippi Goddamn”:

[…] man mother

goddamn the street full

outside where there is white

tomorrow is today the black

walk down fifth avenue, hawkbill

in my hand.[25]

Walking down Fifth Avenue, “the street full // outside where there is white,” Weatherly’s poetic stride accomplishes — at least, in a poem — the instantiation of a new black consciousness and the seizing of political power. “Tomorrow is today the black”: the unconventional grammar here actually makes that “tomorrow” happen “today” by means of the poet’s act of defiance, as they “walk down fifth avenue, hawkbill / in my hand.” The hawkbill is essentially a rural tool, a sickle adapted for defensive and martial purposes, as signal and symbol — perhaps — of Southern origins, turned to radical threat in the Northern city, where the poet stalks armed down Fifth Avenue’s monied center. Against the conventional separation between a Southern strategy of nonviolence, influenced by Martin Luther King, and a Northern practice of self-defense, influenced by Malcolm X, Weatherly brings South to North as gesture of militancy.

“we trespass the blues”: Weatherly’s Coltrane

In “imperial thumbprint,” Weatherly’s hawkbill serves as a weapon, travelling from South to North to threaten the established order. Likewise, in forms ancient and modern, poetic and political, Weatherly’s blues poetry as a whole partakes of the full vocabulary of African American music, Southern and Northern, to “honk [its] hymns.” Hence, for Weatherly as for Amiri Baraka, John Coltrane — champion of the new jazz avant-garde — retains a fundamental blues impulse. Here we find a second instance of cultural weaponization, this time in reverse: whereas Weatherly’s hawkbill travels from South to North, Coltrane’s saxophone travels the reverse route, its New York–based and increasingly international reach connected back to Coltrane’s own Southern roots and his links to the blues traditions.

The second of the Maumau Cantos is entitled “the yellow brick road (for trane),” and somewhat surprisingly places Coltrane alongside the Wizard of Oz. (Surprising, that is, until we recall Coltrane’s own practice of radically re-versioning numbers from musicals — most notably “My Favorite Things” from The Sound of Music, first recorded in 1960 and subsequently a staple of his live shows in versions of ever-increasing length and experimentation: see, for example, 1966’s Live in Japan.) We don’t tend to think of Coltrane as a “Southern” artist — his music was so much forged in New York City, as part of a modernist movement buzzing with the energies and dissonances of urban life, that we forget he spent nearly the first twenty years of his life in North Carolina.[26] However, Weatherly’s poem insists that we switch our focus, framing Coltrane in an “outhouse” or “backyard” of distinctly rural cast.

the yellow brick road

for trane

we trespass the blues

hanging outhouses in picture frames

a record heard

live performance

blow easily

forgotten phrase. we bleep

dont read music. listen

dont move dont you remember

saxophones never die.

titty toad down

remember, read scratchy

sheet music, croak

in the backyard.[27]

In The Wizard of Oz, Dorothy travels the yellow brick road from her rural farm to Oz, the big city — which is, as we remember from Frank Baum, a center of corruption masquerading as a “bright and glorious” place. For Weatherly, the road travels both ways. (Recall Dorothy and “there’s no place like home.”) Weatherly dedicates the poem using the moniker adopted by other musicians and in album titles by which “Coltrane” becomes “Trane,” the train inflected with the movement from South to North and back again (and, in Coltrane’s Africa/Brass sessions, with the “Song of the Underground Railroad”). In this poem, Coltrane’s free jazz exists in dialectical relationship to the blues, productively mining the tension between “a record heard” and “live performance,” sheet music and improvisation: it is simultaneously claimed that “we bleep / don’t read music” and that we “read scratchy / sheet music.”[28]

This double movement is exemplified in the opening line, “we trespass the blues,” which indicates both that Coltrane has “trespassed” the blues for more “advanced” forms and that the blues itself is a form of trespass, its spirit echoed in that of Coltrane’s free jazz performances.[29] Like the hawkbill with which Weatherly stalks Fifth Avenue in “imperial thumbprint,” Coltrane’s undying saxophone is the instrument which serves to modernize and weaponize the spirit of Southern cultural forms.

“that sociological inverse relationship”: Weatherly and sex

I will return to Weatherly’s play on the trespasses of African American musical modernism and tradition at this essay’s close, via a reading of Weatherly’s key blues poem “mud water shango.” However, in order to set up the discussion of sex, ecology, and apocalypse in that poem, I wish to first concentrate on Weatherly’s writing on sex and sexuality, a key part of his oeuvre and his blues poetics. Here we’ll follow Weatherly’s trespass from John Coltrane and the yellow brick road to Blind Lemon Jefferson and Scottsboro, with Weatherly’s blues rooted in the complex questions of interracial sexual relations and the violence in which they are enmeshed.

Weatherly is in many ways a poet of sex. His poems crackle with the energy of vernacular speech patterns which are frequently sexual in content, and oftensexualized even when the subject is not explicitly sexual. Thumbprint begins with a dedication to a litany of ninety-four female figures, and the book opens and closes with the Sumerian symbols for man and woman. The poems within it can be mean, bitchy, sarcastic, and downright cruel as often as they are tender, generous, and loving. Indeed, Bluford goes so far as to call Weatherly’s conception of men and women “fundamentally fucked up.” Words such as “bitch,” “cunt,” and “dyke” recur across these poems: the sexualized language of obscenity is placed back into the scene of sex itself, as Weatherly cajoles, argues, seduces and charts heterosexual relationships and (frequently) their intersection with the complex perceptions and negotiations of racial politics.

Weatherly’s language at times spills over into homophobic and misogynist insult. Yet his treatment of sex — what he calls in the poem “to john wieners” “the drama of / weighing down weight /: the tension of fucking / springs to” — doesn’t resolve into a simple, retrograde split between essentialized ideas of “masculinity” or “femininity” (as, indeed, the dedication to the queer, often gender-bending poet Wieners might further suggest).[30] For Bluford, Weatherly’s use of obscene and gendered words “hurts because it’s idiomatic and not simply abusive”; Weatherly’s sexualized punning and barbed address serves to “keep language in a state of crisis,” “loud and wrong and raunchy.” Gender here often becomes complex and blurred in a way that goes against a surface appearance of macho bluster and posturing, which should be no surprise given that Weatherly frequently cited H.D. as one of his primary influences. As well as the poem for Wieners, we find a queered register in Weatherly’s elegy for then-recently assassinated Martin Luther King Jr., the first of the Maumau Cantos. Via the popular song “There’s No You,” made famous by Frank Sinatra, Jo Stafford, Louis Armstrong, and Frank Sinatra, Weatherly deconstructs the macho tropes of white American masculinity that glorify violence while also addressing King simultaneously as absent brother and absent lover (“my man”): “old western fancy // dude shot my man // dead, / precious lord blow off / theres no willy in th blues theres no you.”[31] In his late writing, Weatherly presents H.D. as both figurative mother and grandmother: “unset tunes never / better hd’s flesh”; “hd // if my mother a lesbian / she’d marry my father / marry never leave him childless”; “[Weatherly] is the grandson of Jimmy Rogers and Sippie Wallace, Hilda Doolittle and Wallace Stevens.”[32] As Rosanne Wassermann notes: “he’d show me rare editions of H.D., whose work he adored and introduced me to.”

Having grown up in Scottsboro, Weatherly had a keen sense of the violence frequently attendant on interracial sexual relations (what he calls “that sociological inverse / relationship”). Such violence can inflect even a loving address. Parodically adapting the stereotypical view of black men that had led to the framing of the Scottsboro boys, Weatherly calls himself in the preface to Natural Process “the Scottsboro buck.” “Bitch hazel-eyed goddess” from Maumau captures the complex interplay between victim and aggressor, reality and fantasy, pleasure and pain that characterizes the lived experience of interracial relationships heightened by Scottsboro. Weatherly mingles the language of misogynist offense and female veneration — which, after all, can be two sides of the same coin. The speaker aggressively commands his white female lover to jettison the traces of racism and lynching, a hurt registered in the language of sexualized obscenity.

my lady bring to my black dick your white cunt

no treed rhetoric for those hounds at me

fuckn commit to our bedroom not bullshit horns

or cattle prods.[33]

“Liz Bitch,” from the same collection, presents this relationship more specifically in relation to Scottsboro.

i’m not the gentle honorable

man of collar

speaks from scottsboro

interested to read that

sociological inverse

relationship, lynchd

& the price of cotton

& not speak in fronts, follown

my life in your free dom.[34]

The poem closes with fused quotations from the English poet Thomas (“Tom”) Campion’s 1617 “Kinde are her answeres” — Campion is the poem’s somewhat surprising dedicatee — and the blues song most famously recorded by Blind Lemon Jefferson as “Prison Cell Blues.”[35]

“Breaks time, as dancers

“From their own Musicke when they stray / lay awake

“and just can’t eat a bite, she used to

“be my rider.

Here are the relevant lines from Campion, set in their original context.

Kinde are her answeres,

But her performance keeps no day,

Breaks time, as dancers

From their own Musicke when they stray:

All her free favours

And smooth words wing my hopes in vaine. […]

Lost is our freedome,

When we submit to women so:

Why doe wee neede them,

When in their best they worke our woe?[36]

And here are those from Jefferson’s version of “Prison Cell Blues.”

Getting tired of sleeping in this lowdown lonesome cell

Lord, I wouldn’t have been here if it had not been for Nell

Lay awake at night and just can’t eat a bite

Used to be my rider, but she just won’t treat me right

Got a red-eyed captain, and a squabbling boss

Got a mad dog sergeant, honey, and he won’t knock off

I’m getting tired of sleeping in this lowdown lonesome cell

Lord, I wouldn’t have been here if it had not been for Nell[37]

Campion’s poem complains at the disjunct between his lover’s “kinde” answers and her actions, “stray[ing]” as “dancers” from the “musicke” of her own words. “Freedom” in both cases is something taken away from men by their female lovers, a theme more explicitly politicized by Weatherly’s critique of the interplay between race and gender relations in the Civil Rights movement. Campion’s more generalized “freedom” has, for Weatherly, to do with societal positioning — the racial and class disjunct between (broadly speaking) middle-class white female activists and their black male lovers, disadvantaged in terms of both race and class — rather than with the curious and disingenuous inversion of gender relations that Campion performs.

This specific Campion poem had been of interest to a number of the New American Poets — perhaps Weatherly’s source — but they had put it to very different use, appearing to have been interested in the poem on almost purely technical grounds. Allen Ginsberg comments on the poem’s “breaking” of the flow of music; William Carlos Williams sees Campion as the “true pioneer” of “free verse”; and Robert Creeley follows up on Williams’s comment in a comparison of “Kinde are her answeres” to one of Williams’s own poems, tracing the poet’s shared distrust of “measure,” proposing instead that the rhythms of poetry might be a “regularity just out of hearing.”[38] For Weatherly, by contrast, Campion’s “Breaks time, as dancers / From their own musicke when they stray” becomes part of a love lament that maps politics onto interracial sexual relationships: “and just can’t eat a bite, she used to / be my rider.” “Rider” here might suggest Freedom Riders as much as the more explicit sexual connotation of the Blind Lemon Jefferson original, the female figure standing in for the still-skewed racial politics of the integration movement: “& not speak in fronts, follown / my life in your freed dom.” Weatherly refuses to be a “gentle” and “honorable” “man of collar” — the variant spelling of “color” for vernacular purposes suggesting also the slave “collar” — whose position as a native of Scottsboro provides social interest to those that “speak in fronts,” yet fails to do justice to the horror of lynching and the system of cotton farming. Such speech, indeed, serves as a “front” which masks an inadequate conception of what the vaunted notion of “freedom” might actually mean for its patronized black subjects.

By recontextualizing Campion’s poem alongside the blues, Weatherly insists on transplanting the poem for social purposes. “Prison Cell Blues” blames the singer’s lover, “Nell,” for his current plight in a “lowdown lonesome cell,” even as a long list of other contributing factors is included — governmental employers, foremen, “a mad dog-sergeant,” “red-eyed captain,” and the like. Campion’s poem too can also be read in the context of prison. As a court poet, Campion understands sexual relation in carceral terms — however obliquely — because of the risks faced when writing for a patron in a context of complex political wrangling. (Campion was implicated in a murder for which he was eventually acquitted.) While the specific Campion poem appears to treat its love complaint exclusively within the sphere of gender relations, bearing this context in mind, and viewing it through Weatherly’s poem and Jefferson’s prison blues, allows us to read the framework of gender relations as a critique of the political system by which they are unavoidably inflected. Unlike Creeley or, more surprisingly, Ginsberg — who did know the real repressive force of a homophobic carceral system — Weatherly’s reading of Campion insists on moving away from the purely formal, insistently foregrounding the motif of prison and the real risks of interracial sex.

While the history of miscegenation laws and anxiety around those laws goes beyond the bounds of the present essay, the above might hopefully suggest the ways in which interracial coupling is exemplary of the trespass with which Weatherly’s poetry is engaged.[39] This is not to say that Weatherly presents such trespass as wholly liberatory. Like his blues-based registrations of trespass as migration, escape, and enforced movement, interracial relationships in Weatherly’s poetry contain both loving possibility and the weight of historical violence. “Liz Bitch” is in a tradition of African American male writing addressing interracial relationships which, explicitly or implicitly, presents the white female as metonymic figure for the false promises of “freedom” promised by integration into white supremacist American society, one which results in the black male’s figurative or literal castration. This stereotype goes at least as far back as James Weldon Johnson’s poem “The Great White Witch,” first published in The Crisis in 1915, and recurs in works by Malcolm X, Amiri Baraka, Eldridge Cleaver, Chester Himes, and Ralph Ellison.[40] In these accounts, white women, as potential accusers, are seen as the cause of acts of violence against black men, which are in fact perpetuated by white men, and which exist as a result of patriarchal and racist conceptions of “race-mixing” and the “purity” of white femininity. Weatherly is writing into a nexus of tangled oppression. The poem cannot untangle these threads, but it might provide some breathing space to think about them, while attesting to the histories of hurt and the language of abuse that contains such histories. In this regard, Weatherly’s alignment with Campion is arch and knowing. The poem is intensely self-aware: it knows that it participates in a history of misogyny, but it also knows that the misogyny that runs through miscegenation laws (a compound of racism and misogyny) is itself part of the courtly tradition from which Campion writes. The “honorable gentleman” from Scottsboro knows, too, that the specter of the black male rapist, and the attendant fear of interracial marriage (seen in white supremacist paradigms as two sides of the same coin), might have disappeared from the majority of American law books, but are still very much a part of a white supremacist cultural imaginary. Indeed, though the Supreme Court invalidated bans on interracial marriage in 1967, Weatherly’s own state, Alabama, did not repeal its antimiscegenation laws until 1999, the last state in the US to do so.

“mud water shango”: Nature, sexuality, and the South

what is heart

is untransplantable

is not the house

we move in, home to[41]

open your front door baby black dark come home for good[42]

As we’ve seen, in Weatherly’s work the pull between South and North, sex and politics, modernity and tradition is a painful and productive encounter, melded in the vernacular-drenched language he made his own. I’ll now conclude this essay by showing how Weatherly’s writing of the blues can offer at least a temporary way out of such dilemmas, through examining one of his few “pure” blues poems, “mud water shango,” the penultimate poem in the Maumau Cantos, a 1965 radio recording of which made its way onto one of John Giorno’s Dial-a-Poem LPs.[43] I’ll set this poem up with regards to its blues-based writing of nature and sexuality, and the ever-present background of ecological and political crisis which inflects it.

Weatherly’s “mud water shango” is, essentially, a straight blues lyric, in which the second line repeats the first, with minor variants, before a new third line. Here is the poem.

mud water shango

a big muddy daddy my daddys gris-gris to the world.

i’m a big muddy daddy daddys gris-gris to the world.

got a mojo chop for sweet black belt girl.

daddys a river & my mamas shore is black.

daddys a river mamas shore is black.

flood coming mama you cant keep it back.

lightning in my eyes mama thunder in your soul.

theres lightning in my eyes mama thunder in your soul.

i’m a river hip daddy mama dig a muddy hole.

Sex infuses and becomes an integral part of the landscape itself as a “river” on “mama’s shore,” an orgasmic breech, with the pun on “flood coming.” Weatherly himself is both the Mississippi River, or “Big Muddy” — “a big muddy daddy” — and its son. “Daddy” and “mama” here are parental — “daddys a river & my mamas shores is black” — but they also represent the sexual coupling of their son, the poet himself. Though elsewhere in the collection rivers tend to be identified with female lovers (“river hips”), in this specific instance the river is male. That the river can be either male or female suggests a kind of ecstatic melding or molding of world through metaphor, a permeability in which “natural” references — river, shore, mud, flood, thunder and lightning, not least to say the poet’s own figuration as a “tomcat” — connect to hoodoo versions of African animist-derived, syncretic religions. Such figures both “naturalize” sexual forces, and, through malleable systems of metaphorical equivalence, enable the fluid act of naming to represent a non-fatalistic shaping of the human by the natural (and vice versa). Natural forces are mythically and sexually tinged in a manner that arguably reinforces the unequal relations of heteronormative sexual discourse, but they are also harnessed against economic and racial systems of inequality, with a world-shattering, world-shaping, apocalyptic force: “flood coming mama you cant hold it back / lightning in my eyes mama thunder in your soul.”

This concern is not just sexual but environmental. An earlier poem in the Cantos, “Southern accent,” is, essentially, an early poem of ecological activism, lamenting the damming and polluting of the Tennessee Valley for “commerce.”

the tennessee valley was author of

lush full forest animal lives

that thrive on the drive of the rain [...]

the tennessee valley is full

of swimming holes dammed for commerce.

catfish swim, creaking in detergents […]

tva built offices where grass was.

dead pond’s beauty screams in the churn

of the bitter turbines whining[44]

Such environmental depredations curb the elemental power of sexualized flood — but they could also cause floods of their own, through damaging the environment, a cost to be felt not only by “catfish” and “lush full forest animal lives,” but by the African American inhabitants of areas polluted by widespread industrialization. The economic greed motivating such measures destroys the environment, which people not only live in but physically identify themselves with through metaphors in blues, song, and poetry. Reading a blues like “mud water shango” alongside “southern accent” thus suggests an ecological motivation to its nature-sex metaphors.[45] Weatherly deploys the nature metaphors that run through the rhetoric of sacred or secular African American traditions — and their animist predecessors — but he is also aware that they are worked figures within a constructed and mutable textual frame. Indeed, I think this is what might allow us to work through the troubling sexual politics of many of the poems. Weatherly’s poems do appear to naturalize certain roles and characteristics in relation to sex; however, race, gender, and nature themselves also appear as constructs which might be troubled at the edges, poses tried out and deposed even as they are sometimes reinforced.

We can draw a further parallel to the poem’s spiritual element: while myth is here thoroughly secularized, the process goes both ways — secular events, whether political or sexual, are infused with sacred traditions whose cultural memory provides sustaining support, images with which to counter white stereotypes and cultural impositions. Hence Weatherly’s self-figuration, in the “autobiography” that begins the book, as “HOLDER OF THE DOUBLE MOJO HAND & / 13th DEGREE GRIS-GRIS BLACK BELT.”[46] The pun here sees the thirteenth degree of Freemasonry joined with the black belt of martial arts joined with the Black Belt South where Weatherly was born and raised. Meanwhile, the mojo hand (also itself known as a gris-gris) is a bag filled with roots, herbs, minerals, goofer dust, and other charms, but Weatherly transforms it back into a real hand: his own two hands are the charms he will use to write his poems. Weatherly holds a bag of charms (a hand) in his own two hands, which themselves have the power provided by those charms (not to mention the connotations of mojo as sexual drive and energy familiar from classic blues lyric). Gris-gris, hoodoo, and conjure traditions thus provide a potent metaphor for the operations of Weatherly’s open poems, but they are not merely modes of self-bolstering. In “mud water shango,” the titular Yoruba deity assumes multiple functions. Initiation ceremonies devoted to Shango represent the most complete of African religious practices to survive the Middle Passage: he is the orisha associated with fire, lightning, thunder, and heavy rain. The historical king Sango, on whose retrospective deification such ceremonies rest, is said to have accidentally destroyed his own palace through lightning, subsequent to which he hanged himself in the forest. The extreme natural forces associated with Shango possess the potential for self-destruction, as well as power and self-control.

Storms as portents of apocalypse are a recurrent figure in works such as Arna Bontemp’s Black Thunder (1936), in which a fierce storm both provides cover for and ultimately scuppers Denmark Vesey’s slave rebellion, or in any number of African American Christian spirituals. In 1963, James Baldwin’s The Fire Next Time took the old spiritual as a warning of the catastrophe that might be unleashed in a race-based civil war, and in many ways can be said to have accurately characterized the spirit of the time. It still haunts us with its spark: “God gave Noah the rainbow sign, no more water but the fire next time.” Weatherly’s thunder and lightning are more obviously a metaphor for sexual energies — unity rather than division, fertility rather than destruction. Yet his, too, seem haunted by both the natural disasters — floods, droughts, starvation — faced by many in the impoverished Black Belt South, especially as these were affected by the environmental depredations of greedy capitalists, as charted in “southern accent,” and, if more obliquely, the political battlegrounds sketched in many other poems from Maumau American Cantos.

What is merely metaphorical and what is all too literal in these poems can be hard to distinguish. Weatherly’s poems mingle sexual affirmation with sexual doubt, the possibility of political resistance with the fact of daily oppression, the urban with the pastoral, the South with the North, the sacred with the profane. Deceptively simple, they contain a world of argument, assertion, allusion, and provocation. Whether wandering down Fifth Avenue, hawkbill in hand, or traveling the land in the spirit of “homer’s blues themes,” singing the Dionysiac “goatsong” of his gris-gris blues, Weatherly, “HOLDER OF THE DOUBLE MOJO HAND & / 13th DEGREE GRIS-GRIS BLACK BELT,” trespasses the boundaries of established schools, forms, assumptions, and ideologies, while tipping his black hat to the traditions of resistant survival, the human response, through art, to inhuman conditions.[47]

His poems are an utterly singular achievement.

1. The titular quotation is taken from a refrain in Tom Weatherly’s poem “wally,” in short history of the saxophone (New York: Groundwater Press, 2006); this poem is included in this Jacket2 feature.

2. Aldon Nielsen, “This Ain’t No Disco,” in The World in Time and Space: Towards a History of Innovative American Poetry in Our Time, ed. Edward Foster and Joseph Donahue (Jersey City, NJ: Talisman House, 2002), 536–46. This essay is included in this feature.

3. Weatherly, “the yellow brick road (for trane),” in Maumau American Cantos (New York: Corinth Books, 1970), 34.

4. See Houston A. Baker Jr., Blues, Ideology, and Afro-American Literature: A Vernacular Theory (Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 1984) and Modernism and the Harlem Renaissance (Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 1987), 101.

5. Tom Weatherly, “Natural Process,” preface to Tom Weatherly and Ted Wilentz, eds., Natural Process: An Anthology of New Black Poetry (New York: Hill and Wang, 1970), v.

6. The African Methodist Episcopal Church was the first independent Protestant denomination to be founded by African Americans in the United States. Growing out of the Free African Society in Philadelphia during the 1790s, the church was founded by those who protested the fact that Methodist Episcopal Churches would allow black preachers to speak only to black congregations, who were made to sit a separate gallery. AME’s founder Richard Allen successfully sued the state courts for the rights of the congregation to exist independently of white Methodist congregations, initially named the Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church, which merged with black members of other Methodist churches to form the AME in 1816. Among notable AME members have been Bishop Henry McNeal Turner, the first black chaplain in the United States Colored Troops during the Civil War, and subsequently a member of the Freedman’s Bureau, who had played an important role in Republican Party politics. Following the betrayal of Reconstruction and the institution of Jim Crow, Turner advocated black nationalism and the emigration of black people to Africa, organizing two voyages to the Republic of Liberia in the 1890s. Black liberation theologist James Cone also comes from an AME background.

7. Weatherly’s marine service is not mentioned in the autobiographical poem that opens his first book, the Maumau American Cantos. According to Rosanne Wasserman, he may have been present at the 1961 Bay of Pigs Invasion. He later opposed the Vietnam War, as noted in his own post on the Left in Alabama blog. Weatherly’s potential presence at the Bay of Pigs forms a curious twist on the history of Beat poetry’s generally sympathetic relation to Cuba, as documented in Todd F. Tietchen’s useful recent book The Cubalogues: Beat Writers in Revolutionary Havana (Gainesville, FL: University Press of Florida, 2010). For the debate on Cuba among contemporaneous American poets, see in particular Amiri Baraka and Ed Dorn’s heated discussions of Cuba and the relation between poetry and revolution during October 1961, recently published in their collected letters, as well as Baraka’s famous essay “Cuba Libre” (1959), in Amiri Baraka and Edward Dorn: The Collected Letters, ed. Claudia Moreno Pisano (Albuquerque, NM: University of New Mexico Press, 2013), 105–17. Baraka’s enthusiasm for Cuba should be set alongside Allen Ginsberg’s later critique of the homophobia present under the Castro government, following his expulsion from Cuba in 1965 (he had been invited to judge the Casa de Las Americas prize). See Robyn Grant, “Seducing El Puente: American Influence and the Literary Corruption of Castro’s Cuban Youth,” Journal of Undergraduate Research 1, no. 5 (2009–10): 1–29. Notable also is the satirical prose piece “A Decoration for the President” by the Umbra poet Ray Durem. Dated April 1961, the same month as the Bay of Pigs invasion, this text takes the form of a letter in which the severed hand of a Cuban orphan is sent to President Kennedy in an act of ironic tribute, and caused much controversy at the time. See Ray Durem, “A Decoration for the President,” in The Heritage Series of Black Poetry, 1962–1975: A Research Compendium, ed. Lauri Ramey (Aldershot, UK: Ashgate, 2008), 246.

8. In a June 21, 2014, post on Facebook, Weatherly posted a poem of five single-word lines — two words of six letters bookending three words of five letters — and jokingly posted below, “Aram I know it’s too wordy.” (The poem reads in its entirety: “sashay / beast / heshe / beast / chassé.”)

10. See M. G. Stephens’s obituary of Weatherly, included in this feature. Weatherly’s Goodreads profile is filled with his pithy reviews, perhaps some sort of rougher parallel to or flip side of his closely worked late poems. One of the rewrites of the earlier poems, “Confederate Cemetery,” is included in this feature.

11. Weatherly, Maumau, 42. See in particular “blues for franks wooten” and “mud water shango,” in Maumau, 45–46.

12. Lytle Shaw, “On Coterie: Frank O’Hara,” Jacket 10 (October 1999).

14. “Africans, whose gods were never suppressed, didn’t have the blues — they had no reason to have them. But a people deprived of religion, language, customs and human dignity did. The first slaves were the first blues people: America, literally, gave the slaves the blues. Under slavery the black mind took refuge in the spiritual resources of its past and tapped (like a well under pressure which finds a new outlet) a hitherto unused part of its godhead […] the blues was all but divested of its religious role: it donned the cloak of secularity. […] The reality is American; the dream is Black.” Julio Finn, The Bluesman: The Musical Heritage of Black Men and Women in the Americas (London: Quartet Books, 1986), 5–6, 232.

15. This dilemma is, after all, one that characterized not only the New York School but the Black Arts Movement itself, as Fabio Rojas has argued in a book on Black Power’s place within the academy. See From Black Power to Black Studies: How a Radical Social Movement Became an Academic Discipline (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2007).

20. See Robert B. Ward, New York State Government: Second Edition (New York: Rockerfeller Institution Press, 2006), 233, and Michael Hirsch, “Three Strikes Against the New York City Transit System,” in The Encyclopedia of Strikes in American History, ed. Aaron Brenner, Benjamin Day, and Immanuel Ness (New York: M. E. Sharpe, 2009), 280.

23. Malcolm X, “The Ballot or the Bullet,” in Malcolm X Speaks: Selected Speeches and Statements, ed. George Breitman (New York: Grove Weidenfeld, 1965, 1990), 23–44.

24. In addition to the connections between anticolonial and domestic politics conjured up by Weatherly’s use of the Mau Mau and Malcolm X, it’s also worth noting here that the Mau Maus (or the Mau Mau Chaplains) was the name of a Puerto Rican New York street gang who operated between 1954 and 1962, and whose former leader Salvador Agron wrote politicized accounts of his experience in a series of prison poems which included “The Political Identity of Salvador Agron” and “Uhuru Sasa! (A Freedom Call).” See Salvador Agron, Annette T. Rubinstein, and Harry Kresky, Salvador Agron: Puerto Rican, Prisoner, Poet (New York: Charter Group for a Pledge of Conscience, 1978). As a side note, Agron was the subject of a controversial musical entitled The Capeman by none other than Paul Simon.

26. The recent film Chasing Trane: The John Coltrane Documentary (2017, dir. John Scheinfeld) does something to redress the balance, though the presence of former president Bill Clinton as one of the talking heads is a bizarre move, to say the least. See also Baraka’s 1979 Marxist-Leninist essay “War/Philly Blues/Deeper Bop,” which situates Coltrane as emerging from what Baraka saw as the oppressed nation of the Black Belt South. A recent article by David Tegnell provides detailed biographical detail on Coltrane’s Southern background: “Hamlet: John Coltrane’s Origins,” Jazz Perspectives 1, no. 2 (2007): 167–214. It’s also worth noting Coltrane’s musical responses to the sufferings of African Americans in the South, most notably “Alabama,” recorded after the Birmingham church bombings in 1963, and “Bakai” (“cry” in Arabic), a tribute to Emmett Till written by Cal Massey and recorded in 1955.

28. Weatherly’s poem anticipates the “Invocation to Mr. Parker,” a recitation by Bazzi Bartholomew Gray that appears on Archie Shepp’s incendiary 1972 album Attica Blues (Shepp himself was a distinctly blues-influenced free player). In Gray’s poem, an advanced saxophone player of “modern jazz” is figured as old-fashioned blues- or backwoods-man, Weatherly’s “croak / in the backyard” finding correspondence with Gray’s “used to wail out back”:

Where’s that driving music man

that used to wail out back?

Never knew where he came from —

could have been a castle, or a shack.

Bazzi Bartholomew Grey, “Invocation to Mr. Parker,” on Archie Shepp, Attica Blues, Impulse Records, 1972.

29. Weatherly’s poem also suggests an implicit awareness of the risk (particularly on the part of a white audience) of a retrospective framing which nostalgically justifies and romanticizes the poverty to which the blues gives witness: as its second line has it, “hanging outhouses in picture frames.” The risks of such framing have in large part to do with the reception of African American cultural forms such as the blues by white audiences and collectors. While the original blues gave ironic and defiant witness to suffering, this reception aestheticizes and depoliticizes the original impulse to protest those conditions (or, for that matter, to celebrate the resilience, humor, and resourcefulness, as well as the despair, to which conditions the blues are the human response). If read this way, Weatherly’s account of Coltrane’s “fram[ing]” — however fleeting — resonates with Amiri Baraka’s deployment of Coltrane, alongside the likes of Albert Ayler, as representative of a tradition of “populist modernism” that had been refined out of existence by the middle-class intellectualism of the so-called “Third Stream” jazz of the 1950s. (See in particular the conclusion to Baraka’s Blues People and various essays in Black Music.) This populist modernism provided renewed access to the impulse of the blues which was blues-like precisely because it did not fit the precise forms of blues and early jazz, but rather explored the forgotten areas — of extended/nonstandard technique, temporal extension, and above all, spirit — that both troubled its edges and constituted its true center. (Coltrane’s free jazz period might thus be more authentically “blues” than the album Coltrane Plays the Blues, for instance.) Though I’m mapping a more comprehensive (and polemical) account of jazz and blues history from Baraka onto only a hint from Weatherly, the argument should be borne in mind if we are to understand what it means for Weatherly to be a blues poet during this period. It’s worth noting further that there’s an ironic delight in Weatherly’s lines: the outhouse is literally a shithouse, and its framing (a framing of a framing, given the metaphorical use of visual art to describe music) metaphorically shits over the frame by which a (white) collector might seek to recuperate it and translate it into monetary value, at the expense of the labor and lives with which it is associated. Conversely, the framing of the shithouse is a framing of the earthy, the dirty, the shitty which transmutes it to art as the blues had done, and as Weatherly’s poetry always sought to do.

30. Tom Weatherly, Thumbprint (Philadelphia: Telegraph Books, 1971), 22.

32. Weatherly, “enter crete adept,” “hd,” and “about the author,” in short history, 23 and 30.

35. See Harold Courlander, ed., A Treasury of Afro-American Folklore: The Oral Literature, Traditions, Recollections, Legends, Tales, Songs, Religious Beliefs, Customs, Sayings, and Humor of Peoples of African Descent in the Americas (New York: Marlowe and Company, 1976), 518–19.

36. Thomas Campion, “Kinde are her answeres,” in The Works of Thomas Campion, ed. Walter R. Davis (New York: Norton, 1970), 141.

37. Blind Lemon Jefferson, “Prison Cell Blues,” recorded May 1928 and released as a 78RPM with “Lemon’s Worried Blues” by Paramount. The song perhaps most famously appears on Harry Smith’s Anthology of American Folk Music, Vol. 3: Songs, Folkways, 1952.

38. Allen Ginsberg, History of Poetry Class, Naropa, June 1975 (transcription online at Allen Ginsberg Project); William Carlos Williams, “Measure,” Spectrum 3, no. 3 (Fall 1959): 133–58; and Robert Creeley, The Collected Essays of Robert Creeley (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1989), 36–38.

39. See Calvin Hernton’s preface to the 1988 reprinting of his controversial 1965 book Sex and Racism in America: “The fact of the matter is, people who trespass across race and sex barriers are fugitives in American society. ‘Fugitive’ is a stigma that all racist societies stamp upon interracial lovers. Almost universally, they are seen as ‘fugitives’ from both the white world and the black world. […] They are always fearful of the public and tend to engage in discreet avoidance tactics. They frequent only safe spaces of recreation, bars, and other haunts where interracial coupling is accepted and where people go to meet others of similar inclinations. They appear to be forever in flight — psychological flight and geographical flight.” Calvin Hernton, 1998 introduction to new edition of Sex and Racism in America (New York: Grove Press, 1990), xvii.

40. It’s worth noting here Johnson himself was nearly lynched for associating with a white woman in Jacksonville, Florida. On Johnson’s poem, see Felipe Smith, “Prospects of America: Nation as Woman in the Poetry of DuBois, Johnson, and McKay,” in Reading Race in American Poetry: “An Area of Act”, ed. Aldon Nielsen (Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2000), 25–42.

43. Weatherly, Maumau, 46; recording on The Dial-a-Poem Poets, LP Giorno Poetry Systems, 1972.

45. In this regard, we could compare Calvin C. Hernton’s late The Red Crab Gang and Black River Poems (Oakland, CA: Ishmael Reed Publications, 1999).

47. The references in this sentence are to the following poems from Maumau American Cantos: “imperial thumbprint” (hawkbill), “court changen race by legal decree” (homer’s blues themes), “Canto 9: lucy belle” (goatsong), “mud water shango” (gris-gris), “autobiography” (“HOLDER OF […] BLACK BELT”), and “Canto 10: wooten” (black hat).

Edited by David Grundy