A poem by Stephen Paul Miller

“It’s Hard to Explain What You Really Like about Rick Perry Anymore”

It’s hard to explain what you really like about poetry anymore.

When I was 17, no I was 25, but 24 or 5 was my poetry 17,

I spoke with John Ashbery about getting poetry out there

And he said let’s keep it our secret, but I think there are 2 Ashberies,

2 of me too, because who likes poetry? Let me explain.

Someone once said I don’t like poetry but I like what you do.

Poetry that is poetry is corn. I know that Ashbery really likes poetry

But underneath it all he knows better. That’s why you like what he does.

He has to hate poetry to like poetry. But owning up to that would make him

The teen I will always be. Some truths are inconvenient. But Ashbery can

Conveniently undermine and trump and qualify and digress from the truth

As it sails over. These things are not supposed to happen yet they do.

Stretching the truth if not overriding it pops the language qua language

Out of poetry, through the theater, and into the hyper definition of your

Weird heart. But Ashbery may not be the greatest poet of the last third

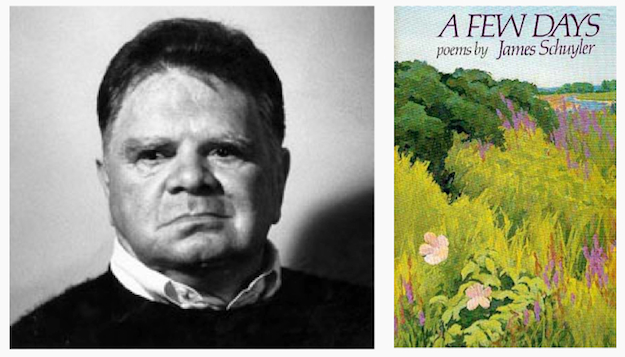

Of the last century. John A. said it was James Schuyler and I believe HIM.

If Ashbery and Schuyler are the two great late twentieth century poets

It is through diametrically opposite though similarly motivated strategies.

Ashbery like a great yet understated Abstract Expressionist painter

Marks shifting frames in alternating objective and subjective authenticities

Wearing one another’s nametags. In other words, he avoids the bull of

So-called poetry by avoiding breaking the plane of real poetry, by being

Strong enough to resist meaning anything outside poetry.

He does not take the bait. Or if he bites he keeps masking the taste,

Spitting it out, getting other stomachs, whatever it takes to mix spookily

Comic cosmic metaphors. But Schuyler does something different.

He takes objects and grinds them into film, I mean like Stan Brakhage,

And “Moth Light” has been on YouTube for years now. Ashbery

Marvels at how Schuyler is not only good but means something,

But only able to do that by “Freely Espousing,” by lapping language

Against itself within its diminutive super bowl: “a commingling sky”

“Cast[ing] the blackest shadow” from the Adam’s rib of “a semi-tropic

Night” that also is “the easily torn, untrembling banana leaf.” In a sense,

“Freely Espousing” is a Kenneth Koch meat in the

Sandwich of another poem-essay, the point spilling out of its eyes is that

“Freely Espousing” lists “marriages of the atmosphere” such as

“Oh it is inescapable kiss” “and tickle” and “Quebec … Steubenville

Is better?” and “the sinuous beauty of words like allergy/the tonic

Resonance of/pill when used as in / “she is a pill.” And yet the euphoria

Of the freely espoused doth bespeak the Schuyler poetry persona,

The truth consistent with that constantly put in his own humbly

Self-topping way. So he’s not that different than Ashbery

Though stagecraft is important too. Schuyler speaking through

Himself is like the “couple who / when they fold each other up / well,

Thrill. That’s their story.” Against this backdrop, using this moth

Light stuff, stuff of thing (thing from the Old English for “coming

Together”) light, Schuyler tells stories of lost stories. “Cultural

Treasures” “have an origin” that the cultured “cannot contemplate

Without horror” (Benjamin). “Back,” within Schuyler’s

“The Payne Whitney Poems” suite paradoxically recalls

These forgotten origins in Benjamin-like mode: “from the Frick. … /

It was nice / to see the masterpieces again, / covered with the striker’s

Blood. / What’s with art anyway, that / we give it such precedence? /

I love the painting that’s for sure. / What I really loved today

Was New York, its streets have / men selling flowers and hot dogs

In them.” “Back” values the street life of New York above that

City’s “masterpieces.” You can just see the “hot dogs” in “flowers”

Seeming more of the day yet somehow more like art. “Back”

Also demonstrates relationships amongst beauty and

The relatively poor and the seemingly uncultured. Ultimately, however,

Juxtaposing Walter Benjamin magnifies for me a slight but huge

Distinction between how to view redemption. For Christians,

And Schuyler during his last years was an Episcopalian,

The messiah has already come and his return will merely restore

Some kind of order and balance. However, for Jews such as Benjamin

And the teen, pre-poet, late sixties, and now and again me,

The messiah “brush[es] history against the grain.” The two messiahs,

Even if the same damn messiah, couldn’t be more different. Oddly,

If only in this respect, Judaism becomes diametrically more radical.

We see this in how Schuyler’s “A Few Days” perpetually prefigures

Death a-coming to end the poem, the death of the poet’s mother

Anticipating the poet’s premonitions of his own imminent death.

Thus the poem is in several ways a perfect story in accord with

How Benjamin’s “The Storyteller” describes one. For Benjamin,

Stories have been replaced by information, data and literate knowledge,

They supplant worldly experiences craftspeople and travelers

Tell like a comingling sky for storytelling likes loose causal

Connections and the proximity of death but modern life demands

Taking strict causality seriously. Modernity puts death behind a hospital curtain

But “A Few Days” see through it, doggedly, with one of Schuyler’s

Most paradigmatic and personal moves, describing plants and vegetation

And other natural subjects like the weather with enthusiastic and reverential

Albeit at times whimsical attention. Schuyler affirms experience and, further,

Death is not usually far from the most forefront in “A Few Days” and

Its musing. Like Frank O’Hara Schuyler’s “A Few Days”

Uses death doubly, to sharpen all that it relates, true,

But also with the greatest specificity. Death becomes a counter to life

Necessary in the linking of its most unrelated its constituents, and

“A Few Days” does the hard work of integrating death within and to

Loosely associated Benjaminesque storytelling components in a long

Poem whereas “The Day Lady Died” shocks us with death’s sudden

Aptness, eating up by first putting it in a sandwich that is all that is

And was and will be everything near and dear to the poem’s speaker.

Both “A Few Days” and “The Day Lady Died” respond to the impersonal

And seemingly objective public space discussed by the early Schuyler

Muse/influence (and subject within “A Few Days”) W. H. Auden

In his “Musée des Beaux Arts” and elsewhere wherein we are

Shown to be depressingly cold to a hot cool of death. “Musée des

Beaux Arts” comments on our excruciating need for Schuyler’s

Benjaminian storytelling mode. Within terms set by this flaky mini-essay,

“A Few Days” immaculately, wonderfully, even magically awaits a death

That if perhaps a part of a welcome, irrefutable order, nonetheless,

This order made accessible through the partial inaccessibility of

Language, bathes us in a self-reflecting death, polite yet radical.

Edited by David Kaufmann