A few words on James Schuyler

A first-time reader of James Schuyler’s poetry could have written my notes for this essay:

Clarity

Loves a list

Letter / diary

Right now, right here

Weather and Light

Addresses, exact addresses

Names of friends

Yet I spent thirteen years editing Schuyler’s letters, years during which I thought of him at least once a day, and at every reading I have given in the past decade or more I read at least one of his poems. Really, I ought to be able to come up with a few new observations about his exceptional poetry.

“A word that’s the poem”

At Schuyler’s best he is that simple and straightforward, that easy to understand, but after the word what is there to do or say but marvel? His poems are elegiac because their present is so real that it is over the moment the poem ends. Schuyler lets the reader live and realize what his poems live and realize, and then the satisfying heartache, the rueful contentment, something is over but not finished, of “a dream you just remember … a day like any other.”

Were he in my shoes what would Schuyler do? Twiddle his pen and lay it down, turn on the TV, take a nap and, oh, “Perhaps there’s time to write a poem / there’s always time to write a poem.” Schuyler wrote art criticism, enough to make a book, because he said he liked to describe. He wrote few book reviews. One was of On the Road. He called it a “boy’s book.” Pretty smart. He had zero interest in manifestoes. There is his statement in The New American Poetry, but it is from a different world, a world of New York, “floods of paint in whose crashing surf we all scramble,” than those of Olson, Creeley, or Duncan. Poetics? I can hear Schuyler burping a yawn. Just get on with it. If you don’t have the gift, where’s the point? He seems to have never studied poetry but read it for pleasure, discovering in his early twenties that he had a talent for writing it and an “innate” — his word — love of words. He wrote poems for readers who, like him, had no investment in upholding official verse culture. He never taught, so he had no flag to pledge allegiance to and no forum in which to separate the “right” way of doing things from the “wrong” way. If the question of how he wrote poems mattered to him, he rarely let on.

If this question matters to you, the path to discovery is in Schuyler’s poems themselves. That Schuyler descends from William Carlos Williams and writes free verse is obvious. That he mastered this form, and by mastery I mean saying exactly what he wanted to say, is also obvious. It is impossible for me to believe that any willing reader has had to learn how to read Schuyler. He delivers the news of the world as he sees, hears, and feels it, and he writes his own thoughts in a voice that over a few pages — open his Collected Poems anywhere — is indelible. He causes you to think that words like “indelible” and “voice” are not worth the breath they take. Schuyler means to communicate, but he is rarely urgent. There is no heavy lifting in a Schuyler poem. He can be trivial — who can’t? — but he has an ear, as his letters show, for pomposity and all high mindedness and stops himself as soon as he hears it in his own writing. He does not demand that you take him seriously, but you do because his effortlessness is enchanting. His poems begin a conversation that the reader is not overhearing but participates in. This reader loves Schuyler’s poems because his lines surprise and delight, and they are fresh. That simple. Are they evergreen? Time will tell.

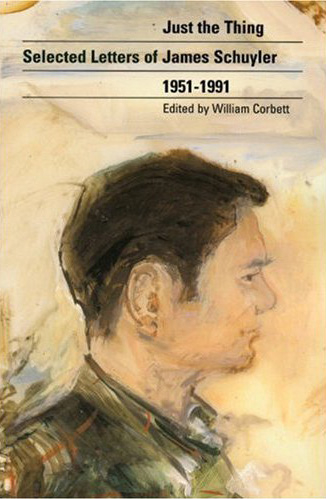

In a letter to me responding to Just the Thing: The Selected Letters of James Schuyler,the poet Jim Cory writes, “Schuyler is famously frank in his poetry, self-examining in a way that places it at a remove from ‘confession.’” “Remove!” Yes, absolutely. In “Trip” from “The Payne Whitney Poems” Schuyler names himself “Jim the Jerk.” He’s not asking for sympathy. There is no “Each of us holds a locked razor” melodrama in any of the “Whitney Poems.” Schuyler knows who he is, and at the end of “Trip” knows that he has survived by luck. It is “a miracle” not because it happened to him, but because it happened and he is alive to tell the tale. “The simplicity of true drama.” You can’t imagine Lowell naming himself, “Cal the Jerk.”

The “remove” Cory hears is in Schuyler’s tone, casual, and matter-of-fact. He is not writing English literature but a lyric poem whose heightened verbal alertness will have to hold and convince the reader on its own terms. You are free to take it or leave it, but either way Schuyler believes what he writes in these lines from the poem “Dec. 28 1974”:

‘Your poems,’

a clunkhead said, ‘have grown

more open.’ I don’t want to be open

merely to say, to see and say, things

as they are.

There is the surface and beneath it … well, there is what the poet knows or thinks he knows, and there are the associations that will insist themselves on the reader, associations the poet cannot know. If there is no surface, there can be no depth. Schuyler is not opening up, but speaking intimately in an impersonal way. A reporter, or observer, if you like, whose gift is, in part, that he is both inside the moments of his poems and outside. And that he has no agenda other than “to say, to see and say, things / as they are.”

What are “things as they are”? At the end of “February” they are “The yellow” … “The shape” … “The water” — all name it but, inevitably, are like “a bit of pink I can’t quite see in the blue.” The reader will often, as Schuyler points out in his “Dear Miss Batie” letter, discover the poem in the same way the poet has. That letter in response to Miss Batie’s thoughts about “February” is the only one I know of in which Schuyler gives a gloss on one of his poems. It ends without his signing off, and possibly he never sent it.

What are “things as they are”? At the end of “February” they are “The yellow” … “The shape” … “The water” — all name it but, inevitably, are like “a bit of pink I can’t quite see in the blue.” The reader will often, as Schuyler points out in his “Dear Miss Batie” letter, discover the poem in the same way the poet has. That letter in response to Miss Batie’s thoughts about “February” is the only one I know of in which Schuyler gives a gloss on one of his poems. It ends without his signing off, and possibly he never sent it.

From his breakdown in the early 1960s that led to his eleven-year stay with Fairfield and Anne Porter and their family through his breakdowns as he left that family and into his very dark New York late 1970s — we will learn more about all of this in Nathan Kernan’s forthcoming biography — Schuyler wrote lucid poems and novels. His art arranged the mess of his life into forms that cohere. Reading Schuyler you will enter a world intensified by his words and their action on your imagination, a world that you will step out of but can step back into at any time and be refreshed.

Rilke believed in angels, that the real world is not here and now but in transcendent realms of the imagination he strove to enter. Poetry was one ladder and painting another. For Schuyler ordinary life is real life. In his last years he found religion, but this might be thought of as the foreordained result of his lifelong communion with the natural world.

Perhaps because his own senses were several times deranged, Schuyler is in his poems, and all of his writing, sane and orderly.

William Blake believed that “where man is not nature is barren.” Wallace Stevens echoed this when he wrote that the “world would be desolate except for the world within us.” Schuyler works the other side of the street. His magic transforms the world without to the world within. When nature is not in man, man will be barren, desolate.

Imagine the poet who takes a “dump,” who studies the “smaller, than small” blackhead on his lover’s back and who hears the “great bronze bong” caught holding Yuban Instant in one hand and Coleman’s Mustard in the other. Mazola, Wesson. “A timer pings.” Imagine the poet who watched The Jeffersons and Mod Squad, who watched television the way regular folks do? One day someone will write a few words on Schuyler’s sense of humor, camp and otherwise.

Frank O’Hara called critics “the bores.” They are everywhere laboring to organize all human activity, squeeze the juice out of life, teach and enact laws that discriminate, set standards, honor tradition — the newspapers, the Internet are full of them and their hot air. But they are not the “news” William Carlos Williams had in mind when he pointed out that everyday men and women die of its lack. He meant poetry and not literal but spiritual death. For many reasons — his numerous breakdowns, the comfort of friends —Schuyler lived outside the world of “the bores” spending grim time institutionalized but serving no institution. He didn’t graduate from college, went AWOL from the Navy and did not hold a job for the last thirty years of his life. His poems celebrate friendship … the truth is that they never say so, would not be caught dead in anything so grand as a celebration. He preferred to send flowers. It is the fine and generous quality of his poems’ attention to the people in Schuyler’s life. He had no project, no urge, it seems to me, to convince himself or others that he needed a reason to write a poem. Title it “Today” and go from there.

What makes Schuyler’s poetry difficult to write about is that it is hard, at least for this lover of his work, to write a sentence that comes anywhere near the verve and genius in his lines. And his verbs! The mouth-filling, mind-clenching physicality of his verbs! Scuds, tugs, chuckles, creaks, sighs, reddens, ripens and smites are not in this essay but that are in the last seven lines of “Today.”

To have written these many words and not mentioned pleasure! After forty years of reading Schuyler’s poetry they still deliver pleasure on every level, most of all the pleasure of being stirred when rereading them. Auden, Schuyler’s sometime patron and friend, thought, pleasure the ultimate critical standard. It took me years to accept this. For too long I thought there had to be an intellectual or moral structure to support what gave me pleasure. Could you just love a poem? Yes, you can, Schuyler’s poems are word and deed.

you plunge your face

in their massed

papery powdery sweetness

and grunt in delight

at their sunset sweetness

Afterthought: What I hope will happen is that Schuyler’s letters and diaries will be published together. If I am around I can point out the errors and omissions in Just The Thing, but I don’t have to be the book’s editor. This book will stand beside Schuyler’s poems reminding readers, if they need to be reminded, that letters and diaries are not lesser than poetry. They are of a piece in the hands of this master.

This essay is for Jim Cory.

Edited by David Kaufmann