Past = past

Some notes on James Schuyler's 'Salute'

Who are they you salute, and that one after another salute you? — Walt Whitman, “Salut au Monde!”

With his first published poem, “Salute,” the poet James Schuyler seems to spring fully formed from the person of the rather mannered prose stylist he had been up to that point. He wrote “Salute” in November 1951 in a mental hospital, in an intense burst of inspiration. No preliminary drafts or sketches are to be found among his papers (which is not unusual for Schuyler), and even the original typescript of the poem is still untraced. However, I suspect that he had been meditating on the central idea, imagery, and even some of the wording for some time, perhaps since the summer of 1950. What he needed were the catharsis of a nervous breakdown plus the catalyst of his recent exposure to Frank O’Hara’s work to bring it forth, and with it his mature poetic voice. In fifteen short lines, “Salute” already suggests, seedlike, much of the thematic material and imagery of James Schuyler’s full-flowered poetic oeuvre.

“Salute” was one of a group of four or five poems that Schuyler wrote in November and December 1951 while recovering from a nervous breakdown at Bloomingdale Psychiatric Hospital, in Westchester County. He had originally been admitted to Payne Whitney Psychiatric Hospital in New York City on October 24, in a manic and delusional state, during which he believed the radio was speaking directly to him and that he was the infant Jesus of Prague. At some point before mid-November he was transferred to Payne Whitney’s Westchester County branch, known as “Bloomingdale,” a much pleasanter situation in a grassy campus planted with mature specimen trees. Schuyler’s friend W. H. Auden paid the bills. Once he was there and on the mend, he characterized his breakdown somewhat cavalierly (it had been frightening for his friends) while seeming to recognize its creatively liberating potential: “Whatever it was it happened very quickly and seems terribly worth while having had happen. I’ll call it a nervous breakdown, and say that I feel better now than I have in years.”[1]

Schuyler had spent the past several years attempting to write novels and stories, in emulation, as he said, of the kind of low-key, Modernist short stories published in The New Yorker magazine. No drafts of novels and only a few stories from this period survive. The three very short stories that were his first published works had just appeared in the summer 1951 issue of the prestigious literary magazine Accent. They are by turns admirable, odd, slightly derivative, and fairly self-conscious. Schuyler and Trevor Winkfield decided not to include them in The Home Book, a selection of miscellaneous prose pieces and poems edited by Winkfield and published in 1977. However, Schuyler had also been writing some poetry since at least the summer of 1950, if not earlier, and had submitted several poems to Accent in August 1951. Most of those early poems appear to be lost. The seven or eight pre-Bloomingdale poems that can be documented as having been submitted to Accent are known in most cases only by their titles. These are: “Things Seen,” “Amalfi,” “Amsterdam” (published posthumously in Other Flowers, 139),[2] “Mountain Crossroads,” “Off Key West,” “Not Here,” “Evening” (which may or may not be the poem published posthumously under that title in Other Flowers, 85), and perhaps “The Mushroom Gatherer’s Familiar” (which may be a story). Some of these poems may have been revised and published later under other titles.

“Salute” and the other poems Schuyler wrote in the hospital are distinctive in that they were directly inspired by his discovery of Frank O’Hara’s work a short time before his breakdown. In particular, “Salute” was derived from O’Hara’s “The Three-Penny Opera,” which had appeared in the same summer 1951 issue of Accent as Schuyler’s three stories there, and may have been, in fact, the only O’Hara poem Schuyler had yet read. Shortly after Accent came out, as Schuyler related in several interviews, John Bernard Myers, the director of the Tibor de Nagy Gallery and a longtime acquaintance, called Schuyler to congratulate him, effusively. After a while, Schuyler turned the conversation by saying the only other writing in the issue he admired was a poem by one Frank O’Hara, whom he had never heard of. Myers, a close friend of O’Hara’s, exclaimed, “Why, he’s here in the room with me right now!” Soon after this, on October 1, 1951, the two poets met at the opening of a Larry Rivers exhibition at the gallery. But Schuyler’s breakdown and hospitalization intervened before the friendship could advance much further.

O’Hara’s “The Three-Penny Opera,” inspired of course by the Brecht-Weill musical, is completely different from “Salute” in tone and subject matter; what Schuyler took from O’Hara’s poem were its abrupt line breaks and what he called its jazzlike “broken rhythm.” Discussing the two poems in 1977, he said:

If you look at [“Salute”] carefully and then read Frank’s poem “The Three Penny-Opera,” you’ll see that my form is entirely taken from Frank O’Hara, particularly breaking a line where it would seem logical not to break it, and leaving such things as a dangling “a” or “the” … What I loved in Frank’s poem, aside from the glitter of style of it, was this broken rhythm. It was almost like listening to jazz, or the kind of jazz that someone like Prokofiev might write.[3]

“The Three-Penny Opera” is a poem in two stanzas of twenty-four and twenty lines each; each stanza is broken about midway by a pair of half-lines. “Salute” is a single-stanza poem of fifteen lines. Both poems achieve their “jazzy” rhythm by breaking lines at places that might seem counter to the natural flow of speech or expectation. Both poems break a word just before an “-ing” suffix: “Air- / ing old poodles” (“The Three-Penny Opera”); “Like that gather- /ing of one of each” (“Salute”). “The Three-Penny Opera” is written in a breezy, confiding tone to which Schuyler also responded, and which helped him find and trust his own voice.

From the hospital, within a week or so of writing it, Schuyler sent a copy of “Salute” to The New Yorker poetry editor Howard Moss. Schuyler had either met or corresponded with Moss a short time before his breakdown, and his first letter to him from the hospital, dated November 27, begins by citing his unexpected hospitalization as the reason he had been unable to accept a recent invitation to stop by for a drink. Moss, a year older than Schuyler, was a respected poet but would be better known as the longtime poetry editor at The New Yorker (1950–1987). He had begun work there in 1948 as fiction editor, and it seems likely that Schuyler had submitted stories to him at some point after his return from Italy in the fall of 1949. In any case, by the time Schuyler came to write him from Bloomingdale, some sort of familiarity had already been established, judging from the jocular tone of the letters (he was already “Howard Moss,” not “Mr. Moss”; by the next letter he would be “Howard”). His November 27 letter included two poems; one, “The Double Gallery” (lost or unidentified) was written before his breakdown, he says. The other, “Salute,” is described as “the only writing I’ve done here, since,”[4] which means that it was written sometime within a few weeks before November 27, 1951.

Moss did not use either poem in The New Yorker, but instead forwarded “Salute” to another editor, Arabel Porter, whom Moss (along with John Lehmann) was advising at that time in the selection of poetry for a new literary periodical to be published by the mass-market paperback reprint house New American Library. After learning of this, Schuyler suggested in a subsequent letter that Moss and Porter also consider the work of his new acquaintance Frank O’Hara, whom he described, with the slight condescension of a twenty-eight-year-old speaking of a twenty-five-year-old, as “one of the Young Harvard set … I’ve met him in what I’ll call the John Myers (whom I adore) bunch. What I’ve seen of his poems I’ve thought awfully good.”[5] Moss and Arabel Porter took Schuyler’s recommendation, and both “Salute” and O’Hara’s “Poem” (“The eager note on my door said ‘Call me’”) were accepted for publication in the first issue of New World Writing, which came out in April 1952. Schuyler was still in the hospital when he got the good news of the poem’s acceptance. On December 31, he wrote Moss, “I’m pleased about the poem: how wonderful to be in something brand new, and that is not (I confess this pleases me) printed on an old ditto machine in a converted loft on East West Street.”[6]

New World Writing was indeed a mainstream, rather conservative venue for Schuyler’s first published poem to appear in. For this inaugural issue, Arabel Porter had elicited work from some of the big names of the day, and “Salute” appeared alongside contributions by Christopher Isherwood, Louis Auchincloss, Tennessee Williams, Flannery O’Connor, Thomas Merton, Rolfe Humphries, Shelby Foote, Gore Vidal, Wright Morris, William Gaddis, Howard Nemerov, James Laughlin and others. The fact that a mass-market reprint house was bringing out a serious literary magazine for new writing — fiction, poetry and criticism — attracted media attention, and Time magazine reviewed that first issue, albeit tepidly (and without mentioning Schuyler): “The selections are devotedly serious, they reflect solid craftsmanship, they are only rarely arresting.”[7] New World Writing would go on to be a highly regarded literary vehicle through the ’50s and ’60s, publishing chapters from the books that became Catch 22 and On the Road in issue number 7, for example.

New World Writing was indeed a mainstream, rather conservative venue for Schuyler’s first published poem to appear in. For this inaugural issue, Arabel Porter had elicited work from some of the big names of the day, and “Salute” appeared alongside contributions by Christopher Isherwood, Louis Auchincloss, Tennessee Williams, Flannery O’Connor, Thomas Merton, Rolfe Humphries, Shelby Foote, Gore Vidal, Wright Morris, William Gaddis, Howard Nemerov, James Laughlin and others. The fact that a mass-market reprint house was bringing out a serious literary magazine for new writing — fiction, poetry and criticism — attracted media attention, and Time magazine reviewed that first issue, albeit tepidly (and without mentioning Schuyler): “The selections are devotedly serious, they reflect solid craftsmanship, they are only rarely arresting.”[7] New World Writing would go on to be a highly regarded literary vehicle through the ’50s and ’60s, publishing chapters from the books that became Catch 22 and On the Road in issue number 7, for example.

In the meantime, throughout December, Schuyler had been sending Moss additional poems, at his invitation. These included the still-unpublished “Rome, December 1948,” an elegy “Harold Ross” (dated December 6, 1951), and two untitled short poems, beginning “Good days and bad …” and “Having felt so extremely …” One of the poems he sent, Schuyler said, had been written eighteen months previously, which would date it to the summer of 1950. This could have been “Rome, December 1948,” or possibly “At the Beach,” the poem that was eventually accepted by Moss for The New Yorker and published there in July 1952. The fact that the manuscript for “At the Beach” is not with Schuyler’s letters to Moss, housed in the Berg Collection at the New York Public Library (nor is it in the New Yorker archive, also at the New York Public Library), does not rule out the possibility that it too could have been sent to Moss from Bloomingdale at this time. In early January, after being released from the hospital and before returning to New York, where a new job in the Holliday-Periscope Book Shop awaited him, Schuyler made a brief visit to his parents in East Aurora, New York. From there he sent Moss what must have been his first collage poem, incorporating items from the local Suburban Reporter and Shopping Guide. All five poems of the additional poems known to have been sent to Howard Moss have their merits, and “Rome, December 1948” is especially good, but none is of a quality comparable to “Salute.” Moss would remain a friend and supporter of Schuyler and his work up to his (Moss’s) death in 1987. In all, Schuyler’s work appeared in The New Yorker eleven times during his lifetime, and twice posthumously (so far). Moss also included Schuyler’s story, “Life, Death and Other Dreams” in his anthology The Poet’s Story, published in 1973. His perceptive review of The Morning of the Poem, published in The American Poetry Review in 1981 under the title “Whatever Is Moving,” became the title essay of Moss’s book of essays published the same year.

The significant place of “Salute” in his work was acknowledged by James Schuyler throughout his life. It was the title poem of his first (privately printed) book of poems (Salute, Tiber Press, 1960) and the concluding poem of his first commercially published book of poems (Freely Espousing, Doubleday Paris Review Editions, 1969). When Schuyler’s Selected Poems was published in 1988, the only change from the original order of poems taken from Freely Espousing was to move “Salute” to the beginning of that section, and of the book itself. (In the posthumous Collected Poems, it was moved back to its original place at the end of Freely Espousing.) Late in life, when Schuyler gave a series of remarkable public readings, “Salute” was the poem he invariably led off with. Those who were lucky enough to have attended any of those readings, or listened to a recording, will remember the sound of his gruff, deliberate voice as he read it. Let’s give a listen:

Salute

Past is past, and if one

remembers what one meant

to do and never did, is

not to have thought to do

enough? Like that gather-

ing of one of each I

planned, to gather one

of each kind of clover,

daisy, paintbrush that

grew in that field

the cabin stood in and

study them one afternoon

before they wilted. Past

is past. I salute

that various field.[8]

*

“Past is past.” The poem begins with a truism almost trite, which could also be a humorously deflating rebuttal to the opening lines of T. S. Eliot’s “Burnt Norton”:

Time present and time past

Are both perhaps present in time future,

And time future contained in time past.[9]

But as a piece of homespun wisdom, it is possible that the expression “Past is past” came to him through the trio of remarkable women who helped shape James Schuyler’s childhood: his mother, his grandmother, and his great-aunt. Schuyler’s great-aunt Margaret Godley died in 1926, before Schuyler could have known her (although she did meet him as an infant), but she helped raise both his mother and his grandmother and was a dominant figure in their early lives. Schuyler’s maternal grandmother, Ella Connor, born in 1862, who had been a schoolteacher and farmer’s wife on the Minnesota frontier, in turn helped raise young James after his parents’ divorce. While she was living with James and his mother in Washington, DC, Ella took him to museums and parks and taught him the names of flowers and birds. Some of Ella’s, Aunt Margaret’s, and his mother’s sayings eventually made their way into Schuyler’s work. One that is specifically attributed to Aunt Margaret in Schuyler’s Diary is “Don’t sit down like a spoonful of mush!,”[10] which is also quoted by the grandmother, Biddy, in What’s for Dinner? as a saying of her grandmother, adding (as Schuyler must have heard his mother or grandmother do): “I can hear her now.”[11] Another Schuyler work that begins with a homely maxim is A Picnic Cantata, which starts, “I feel funny today / but you know what they say: / falls to the floor, / comes to the door.” Earlier in the same April 1988 Diary entry, Schuyler attributes “Falls to the floor, comes to the door” to his mother, and recalls that she “always had a ready proverb …”

But as a piece of homespun wisdom, it is possible that the expression “Past is past” came to him through the trio of remarkable women who helped shape James Schuyler’s childhood: his mother, his grandmother, and his great-aunt. Schuyler’s great-aunt Margaret Godley died in 1926, before Schuyler could have known her (although she did meet him as an infant), but she helped raise both his mother and his grandmother and was a dominant figure in their early lives. Schuyler’s maternal grandmother, Ella Connor, born in 1862, who had been a schoolteacher and farmer’s wife on the Minnesota frontier, in turn helped raise young James after his parents’ divorce. While she was living with James and his mother in Washington, DC, Ella took him to museums and parks and taught him the names of flowers and birds. Some of Ella’s, Aunt Margaret’s, and his mother’s sayings eventually made their way into Schuyler’s work. One that is specifically attributed to Aunt Margaret in Schuyler’s Diary is “Don’t sit down like a spoonful of mush!,”[10] which is also quoted by the grandmother, Biddy, in What’s for Dinner? as a saying of her grandmother, adding (as Schuyler must have heard his mother or grandmother do): “I can hear her now.”[11] Another Schuyler work that begins with a homely maxim is A Picnic Cantata, which starts, “I feel funny today / but you know what they say: / falls to the floor, / comes to the door.” Earlier in the same April 1988 Diary entry, Schuyler attributes “Falls to the floor, comes to the door” to his mother, and recalls that she “always had a ready proverb …”

“Past is past” is also reminiscent of Gertrude Stein’s famous circular “concrete poem,” “rose is a rose is a rose.” But rather than being truly circular, the phrase is a kind of near-palindrome, as Eileen Myles points out, both in itself and in its repetition at the end of the poem.[12] Actually, the entire poem is in a sense palindromic, with at its center the generative (retrospective) “eye” of “I planned,” cupped on either side by the pair of nearly identical phrases, “gather- / ing of one of each” and “to gather one / of each,” and with “past is past” and the title itself occurring both at the beginning and near the end of the poem. One might diagram the quasi-palindrome of key phrases in the order in which they occur thus:

Salute

past is past

gather one of each

I planned

gather one of each

past is past

salute

Pared down to this core, “Salute” reveals a crystalline inner structure. Like a mathematical equation, it holds, as it were, a mirror up to itself. Opening from a self-contained seed or bud, it is centripetal like a flower. “Salute” can be studied like a flower, and doing so, we discover a reflection of our own action: the poet studying wildflowers, or at least planning to.

The narrative of the poem presents an event that, while we are told it did not actually happen, is nonetheless vivid as a possibility, and as such, becomes the poem’s primary image: the narrator picking wildflowers in a grassy meadow on a summer day and systematically studying them as they wilt. Although the poem does not specify just where the grasses and flowers were to have been studied, this reader has always envisioned it happening in the field itself, with the poet lying prone. For Schuyler, the image of lying in a summer field held deep associations, extending back to his first awakening to what he “meant / to do.” As he recalled in several interviews, the moment the teenaged Schuyler first realized he would become a writer occurred while he was lying in his tent in his East Aurora, New York, backyard, and looked up from the book he was reading to see the landscape “shimmer” before his eyes. The book in his hands on that occasion — in which a very similar epiphany is described by its author — was Logan Pearsall Smith’s autobiographical memoir Unforgotten Years, and the chapter he was reading was the one in which Smith recalls his youthful friendship with Walt Whitman: the author, of course, of the book called Leaves of Grass. Which itself begins with the poet lying in a field and contemplating “a spear of summer grass.” Again there is the sense of endless mirroring, here coupled with the idea of a continuing literary legacy, specifically, one might add, of gay male writers. “Who are they you salute, and that one after another salute you?”

Like Whitman in “Salut au Monde!” Schuyler was using the word “Salute” to convey a comradely greeting and pay homage to a place, which is also in a way the poet himself. According to the OED, “salute” once had a secondary meaning, now obsolete in English (except when offering a toast) of “safety, well-being, salvation.” Derived from the Latin salud, this sense survives and in most romance languages, including Italian, where salute means “health.” Schuyler had lived in Italy, spoke Italian, and as we will see, had already expressed the phrase “past is past” in that language. Titling his breakthrough poem, written in a hospital, with a word connoting health implies a connection in Schuyler’s mind between (mental) health and this poem, and perhaps by extension, the writing of poetry in general, a connection that could be explored in detail elsewhere. Suffice it to say here that, with few exceptions, Schuyler’s poetic voice seems a paradigm of calm sanity, in marked contrast to his intermittent nervous breakdowns, hospitalizations, periods of delusional behavior, and sometimes messy, on-the-edge existence.

The poem itself, and the believable nature of Schuyler’s work in general, convince us that “that field / the cabin stood in” was a real place, and the idea of making a wildflower “gathering” there an actual one in Schuyler’s life at some time. Although it’s not possible (or that important) to pinpoint the setting with absolute certainty, there is circumstantial evidence to suggest that it was the cabin he and his then-lover Bill Aalto rented near Lac St. Jean in northern Quebec in the summer of 1945 that was in Schuyler’s mind. For one thing, the flag of the city of Montreal, where Schuyler and Aalto stopped on their way to their cabin, incorporates stylized images of four emblematic flowers or grasses, symbolizing the nationalities of the city’s original settlers, arranged in the quadrants of a heraldic “field.” One of them is the shamrock or three-leaved clover (the others are the Lancastrian rose, the Scottish thistle, and the fleur-de-lis). If Schuyler had actually thought of making a “gathering of one of each” kind of wildflower while he was at the cabin in Canada, the sight or memory of this flag might have unconsciously helped put the idea in his mind. And one of the things one traditionally “salutes,” of course, is a flag.

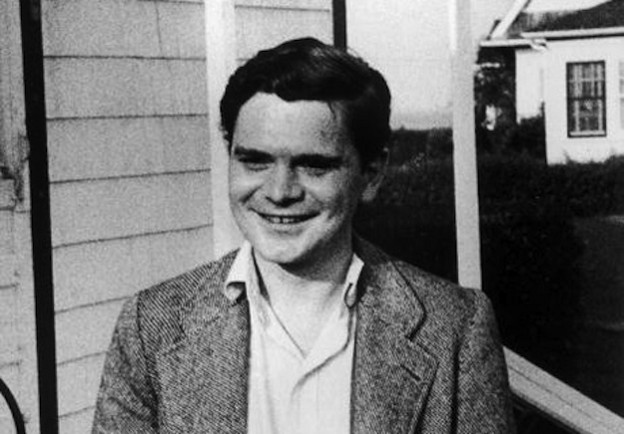

James Schuyler, John Ashbery, and Kenneth Koch, 1956.

More relevantly, Schuyler had already used the phrase “past is past,” albeit transformed into Italian as “una cosa passata è passata” (“something past is past”) in a 1950 letter to an Italian friend, where it referred to his failed relationship with Bill Aalto, with whom the Canadian cabin was associated, and with whom he had more recently traveled to Europe in 1947–49. In the letter, Aalto is described as someone forever looking into a mirror — a metaphorical mirror of self-doubt — and with being obsessed with the past: with his own tragically unrealized talents and ambitions, as well as with the failed relationship with Schuyler. In 1951, in fact, the words “what one meant / to do and never did” were at least as heavily freighted if applied to Aalto, a former guerrilla hero in the Spanish Civil War who had remade himself into a historian with ambitions to write important books, but was instead leading an aimless, almost hustler existence in the south of France, as they would be if applied to Schuyler himself. Although he had not seen or spoken to Aalto in over two years, theirs had been longest and most important romantic and sexual relationship in Schuyler’s life up to that point; he, and a place where they had been happy together years before, might well have been in Schuyler’s mind as part of the personal stock-taking that would have followed his breakdown. But this is not at all to suggest that the poem is “about” Aalto or their relationship, of course.

“Clover, / daisy, paintbrush.” The three wildflowers that Schuyler chooses to mention with such seeming casualness are all rich in connotations, in general and for Schuyler personally. Of course we do not read Schuyler — who famously wrote “All things are real / no one a symbol” — looking for symbols. But certain emblematic images and words are frequently encountered in his poems (including flowers, leaves, grass, air) and it may be useful at times to try to identify some of the associations either the reader or the poet might make with them. But of course, with all such literary connotations it is the same as with the names of roses: as Schuyler wrote, “After learning all their names — Rose / de Rescht, Cornelia, Pax — it is important to forget them.”[13]

That said, it must be acknowledged that the trifoliate clover is a common symbol of the Christian concept of the Trinity, or the three aspects of God: Father, Son, and Holy Ghost. In fact, Schuyler refers explicitly to clover’s association with the Trinity (while giving a sidelong recapitulation of “Salute”) in his 1971 poem “Our Father” (also written in a mental hospital):

how green

the grass! so many

flowering weeds

Your free

will has freely

let us name: dandy-

lion (pisse-en-lit)

and, clover

(O Trinity)

it is

a temptation

to list them all …[14]

Schuyler had an on-again, off-again attraction to Roman Catholicism throughout his life, and certainly one of the things he might have “meant / to do” at several times in his life was to join the Catholic Church (he did finally join the Episcopal Church in 1989). In college he regularly attended Catholic services (though he had been confirmed as a Methodist) and classmates assumed he was a Roman Catholic. His delusional episodes often included religious imagery and a self-identification with Christ.

Daisy was Schuyler’s mother’s middle name, and it is also a common nickname for Margaret, which was her first name, so in effect, her two given names mirror or restate each other. Margaret Daisy Connor Schuyler Ridenour — Schuyler gives her full names when he ends A Few Days with the news of her death — was a formidably intelligent and somewhat contradictory person. Obviously the poem is not “about” her either, yet there is her name, “accidentally” in the middle of Schuyler’s first published poem, as it also concludes the last book of new poems he published during his lifetime.

The common daisy’s golden center and raylike petals form an emblematic image of the sun, to which it responds anthropomorphically by opening itself to it. As such, it exemplifies Keats’s image of the Poet, when he enjoins: “let us open our leaves like a flower and be passive and receptive.”[15] A common and ingenuous flower, daisies can suggest childlike innocence or love. In the child’s game “She-loves-me, she-loves-me-not …” petals are pulled from a daisy as love is alternately given or withheld: an ambivalence that Schuyler may have sometimes felt from his twice-named mother. The association a reader might make between a daisy and the children’s word game very subtly suggests a correspondence between words (of a poem, like the one we are reading) and the petals of a flower, as it also recalls the endless circularity of “rose is a rose is a rose” and “Past is past.”

There are several summer-blooming North American wildflowers known as paintbrush or Indian paintbrush. Whichever was meant (Indian paintbrush with its red flower and straight stem most closely resembles a paint-laden artist’s brush) it was surely the appeal of its name that led Schuyler to put it in the poem. The popular name “paintbrush” personifies nature in a manner already Schuylerian by seeming to hand her the means to portray herself. The image of a paintbrush can denote in traditional iconography the discipline of painting, an art with which Schuyler was deeply involved on several levels throughout his life: as gallery employee, art critic, museum administrator, and through close relationships with many painters. It can also connote creative art in general, and of course it was primarily as a creative artist, a writer, that Schuyler “meant / to do” something meaningful.

If, as Eileen Myles puts it, “the tone of ‘Past is past’ is both Gertrude Stein and Mom,”[16] the tone of what is perhaps the poem’s other key phrase is rather Henry James. “If one / remembers what one meant / to do and never did, is / not to have thought to do / enough?” poses a question one can almost hear a character asking in one of Henry James’s many tales of artists and writers and their dilemmas and scruples, expressed here in formal and convoluted language suitably Jamesian. The problem or the premise is not quite that which James presents in “The Middle Years” through the character of the dying writer Dencombe, who declares, “The pearl is the unwritten — the pearl is the unalloyed, the rest, the lost!”; nor exactly that of the serenely unambitious painter Bilham in The Ambassadors, who “had an occupation, but it was only an occupation declined,” but it feels akin.[17] James, the veritable poet of principled resignation, was one of Schuyler’s favorite writers at this time, and his recent trip to Europe had included several specifically Jamesian pilgrimages, visiting places that James had written about or stayed in, and generally reenacting the role of the searching Jamesian American in Europe. After returning from Europe, he perhaps continued to see himself and his struggles to write in knotty Jamesian terms. If so, such associations could also be unconsciously echoed in the names of the three wildflowers mentioned in the poem. Clover Adams, the wife of the writer Henry Adams, was a close friend of Henry James, and is said to have been a model for certain aspects (not least her floral nickname) of the character Daisy Miller, one of James’s most famous Americans abroad. (As a boy, Schuyler might have seen Augustus Saint-Gaudens’s haunting monument to Clover Adams in Washington’s Rock Creek Cemetery during one of his outings to the adjacent Rock Creek Park with his grandmother Ella.) While “paintbrush” in this context again recalls Henry James’s preoccupation with the problems of art and artists.

In seeming to postulate the primacy of imagination over action, the question touches on an important aspect or problem of Schuyler’s own life and sensibility, he who for stretches of his life would passively let himself be cared for, or not, and take no decisive action, who once declared himself “more of a reader than a writer” (a statement that can be understood in the largest sense, as I attempted to show in my introduction to his Diary). In short, there were times when he may have been close to believing that thinking instead of doing was enough. That being so, the swerve that the poem takes in the fifth line, “Like that gathering of one of each …” functions as a kind of straw man. For by its choice of example, the poem pretty much forces us to agree that it really is just as well to imagine making a physical inventory of every species of wildflower in a field as actually to do such a thing. Within the terms set by the poem, the proposition of not doing something seems reasonable, even beautiful, as if to support, by extension, Schuyler’s own tendency to do nothing, or not enough, at times when it is not reasonable (or beautiful).

In seeming to postulate the primacy of imagination over action, the question touches on an important aspect or problem of Schuyler’s own life and sensibility, he who for stretches of his life would passively let himself be cared for, or not, and take no decisive action, who once declared himself “more of a reader than a writer” (a statement that can be understood in the largest sense, as I attempted to show in my introduction to his Diary). In short, there were times when he may have been close to believing that thinking instead of doing was enough. That being so, the swerve that the poem takes in the fifth line, “Like that gathering of one of each …” functions as a kind of straw man. For by its choice of example, the poem pretty much forces us to agree that it really is just as well to imagine making a physical inventory of every species of wildflower in a field as actually to do such a thing. Within the terms set by the poem, the proposition of not doing something seems reasonable, even beautiful, as if to support, by extension, Schuyler’s own tendency to do nothing, or not enough, at times when it is not reasonable (or beautiful).

Compared to many poets, James Schuyler was a late bloomer. In November 1951 he had just turned twenty-eight. He did not have a job and was being supported by his lover, Charles Heilemann (who himself had had ambitions to be a serious painter, but was making a living as a commercial illustrator and teacher). It had been at least twelve years since he had made the solemn decision to be a writer, lying in that East Aurora field, and he still had almost nothing to show for it except the three very short stories published in Accent. The stated purpose of his recent two-year sojourn in Europe with Bill Aalto had been to write a novel and stories, but no novel was written, and of the early stories that have survived none can definitely be dated to that period (although it is certainly possible that one or more of the Accent stories were written there).

“If one / remembers what one meant / to do …” If the poem is in part a personal stock-taking, it begins with resignation and the “Jamesian” suggestion that maybe to have meant to be, say, a writer was somehow a creative act in itself. Suggesting otherwise, he had the object-lesson of Bill Aalto (with whom the phrase “past is past” had already been associated)and other friends who never lived up to creative ambitions they originally set themselves. But now, he also had the positive inspiration of an exciting new friend, Frank O’Hara, whose work had shown him in practical, formal terms a way to go forward.

Though the poem’s surface narrative deftly changes the — unacknowledged — subject away from Schuyler’s early ambition to be a writer, to tentatively suggest that maybe it’s OK not to follow through on many ambitions, the poem itself, by its very existence, goes the other way. The solid fact of the poem triumphantly contradicts is own ambiguous message. The writing of “Salute” changes everything, even the past, even “Salute.” In the poet’s very act of resigning himself to not having done what he meant to do, he finally does it. The lovely, sad, possibly “unhealthy” dream that anything at all is possible, a dream which can only be kept alive by never actually settling on the thing to be done, is dissolved. In its place is the far more satisfying act of writing the poem, with all the unexpected discoveries and transformations that only the putting of words to paper can miraculously lead to.

Author’s note: “Salute” and other quotations from the poems of James Schuyler are used by permission of Farrar, Straus and Giroux and the James Schuyler Literary Trust. Copyright © the James Schuyler Literary Trust. Quotations from James Schuyler’s letters to Howard Moss are used by permission of the Henry W. and Albert A. Berg Collection of English and American Literature, the New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations. I would like to thank Douglas Crase, Raymond Foye, Jonathan Galassi, Eileen Myles, Charles North, and Tony Towle for reading earlier versions of this essay and offering valuable advice.

1. Schuyler, A.l.s. to Howard Moss, Nov. 27, [1951], 2 p. (2 leaves). The Henry W. and Albert A. Berg Collection of English and American Literature, the New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations.

2. Schuyler, Other Flowers (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2010).

3. Schuyler, from interviews with Peter Schjeldahl, January 3–4 and 10, 1977. Transcription in the collection of the author.

4. Schuyler, A.l.s. to Howard Moss, Nov. 27, [1951].

5. Schuyler, T.l.s. to Howard Moss, “Monday” [Nov. 1951?], 2 p. (1 leaf). Berg Collection.

6. Schuyler, T.l.s. to Howard Moss, Dec. 31, [1951], 2 p. (1 leaf). Berg Collection. This description anticipates by over a decade Ted Berrigan’s C magazine and similar Lower East Side stapled publications, which Schuyler would come to value much more highly than corresponding mainstream periodicals.

7. “Books: The Better Things,” Time, May 12, 1952.

8. Schuyler, Collected Poems (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1993), 44.

9. T. S. Eliot, Collected Poems 1909–1962 (London: Faber and Faber Limited, 1974), 189.

10. Schuyler, The Diary of James Schuyler, ed. Nathan Kernan (Santa Rosa: Black Sparrow Press, 1997), 261 (April 20, 1988).

11. Schuyler, What’s for Dinner? (Santa Barbara: Black Sparrow Press, 1978), 15.

12. Eileen Myles, The Importance of Being Iceland (Los Angeles: Semiotext(e), 2009), 204.

13. Schuyler, Collected Poems, 218.

15. John Keats, The Letters of John Keats, ed. Maurice Buxton Forman (London: Oxford University Press, 1931), 1:112 (February 19, 1818).

16. Myles, The Importance of Being Iceland, 204.

17. Henry James, The Short Stories of Henry James (New York: The Modern Library, 1945), 313; James, The Ambassadors (London: Penguin Books, 2003), 146.

Edited by David Kaufmann