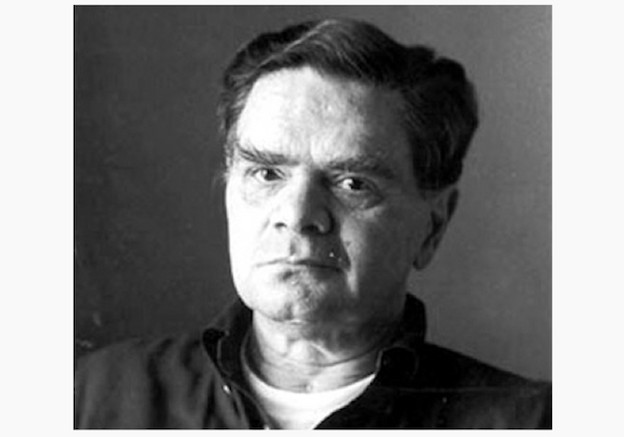

Days and nights with James Schuyler

I still remember David Shapiro’s and Ron Padgett’s Anthology of New York Poets, with its picture of bright red cherries, a butterfly, and a ball and jacks on the cover, promising childlike verve. I ran across it in some New Jersey public library at the age of oh, about twelve, a few years after the book came out in 1970. The Shapiro-Padgett anthology trumpeted freshness — most of all, for me then as now, in the poems of James Schuyler.

Schuyler never shared the game-playing inclinations of Kenneth Koch or (at times) John Ashbery; there is no verbal hopscotch in his poems. There is little or nothing in Schuyler that is arch, intricate, or eccentric in the aesthete’s way. Occasionally he is campy; but Schuyler, conscious of his own awkwardness, defangs the rank-pulling effect of the camp — and for that we are grateful. (No man as awkward as Schuyler was can be a convincing purveyor of camp.) In Schuyler you will find none of O’Hara’s coiled wit-bombs and signposted exultations, none of Ashbery’s secluded, secretive chills. You can imagine him immersed in Heine or Herrick or John Clare, but not Baudelaire (though Baudelaire is mentioned in The Morning of the Poem and looms there for a few pages, Schuyler dispels him effectively). Alone among the New York School poets he has a pure, moving relationship with the late long poems of Williams. Sentiment is a natural phenomenon in Schuyler’s poems, and welcomed as such, frankly or bluntly. Sometimes the sentiment is scarily obsessive, as when he repeats Tom Carey’s name like a chant in “O Sleepless Night” (a poem I will return to, since it is among my favorite Schuyler).

Like his friend and lover, the great painter (and remarkable art critic) Fairfield Porter, Schuyler is devoted to innocent clarity. Many an offhanded sentence participates in this clarity, as when in the course of the long titular poem at the end of A Few Days Schuyler notes:

I hate to miss

the country fall. I think with longing of my years in

Southampton, leaf-turning

trips to cool Vermont. Things should get better as you

grow older, but that

is not the way. The way is inscrutable and hard to handle.

Over its several dozen pages “A Few Days” mostly darts around its ostensible subject, the death of Schuyler’s mother (Schuyler finishes by avoiding her funeral): it skips understatedly from one mental station to another, “leaf-turning.” Schuyler’s characteristic method is browsing; he ruffles the pages in his head. Love, food, pills, dead friends, memories of drinking: it’s all there. And occasionally Schuyler comes upon a hard, plain place: “The way is inscrutable and hard to handle.” With what expression are these words pronounced? A sigh, a grimace, a blank oracular face? What’s remarkable is the sheer honesty of the line: there’s no way to dress it up.

Probably no poet has shown himself in so unpleasant a light as Schuyler does at times in The Morning of the Poem. As he says, he can be “Jim the Jerk” — not the fabulous colossal jerk played for laughs, but a real one: vindictive. Schuyler does not glory in his moral failings, and there is in his poems none of the Grand Guignol of Confessionalism. There is no gloating, no indulgence, and no special pleading on the grounds of the harrowing miseries he has endured (addiction, suicide attempts). There is, instead, the simple bravery of admitting who he is. Schuyler can be obstinate, unforgiving, hurt, malicious. It would be wrong to deny this sometimes unlikeable side of his work. Schuyler himself would have been the last person to deny it.

But there is also love, and love in Schuyler tends toward the crazy. “O Sleepless Night,” from A Few Days, begins with the poet’s memory of being awakened with a kiss by Fairfield Porter; it ends with Schuyler, insomniac and counting “creepy sheep,” drumbeat-yearning after the kiss of his young secretary, Tom Carey (“Tom Tom Tom, I want my Tom: / Tom Tom Tom, where’s my kiss?”). In between there is Schuyler’s rapturous argument with F. Scott Fitzgerald:

… three a.m.:

“the Dark Night of the Soul”

about which F. Scott Fitzgerald

was mistaken: he

thought it was some sort of sudden unendurable angst

or anguish or plunge into the pit of hell:

no:

it is the moment

when a mystic like St. John of the Cross

kneels outdoors

and

prays: his

very soul

rises in a beam or column or like morning mist

and intermingles

with the divine essence of the Godhead:

love, love, love,

pure and unalloyed, simon-pure, the real thing:

beyond, way far beyond

all human comprehension:

love, pure love, its essence:

gilded clouds, rainbows, no sky, no moon, no sun, no stars,

and yet

light

gentle and bright

light:

Angels, Archangels, Cherubim, Seraphim and Cupidons

choiring together

melodiously

in song that is not plainsong

to the music of plucked harps, wind harps, o-

carinas and the nose flute

and the oot of instruments: most beautiful of all,

the pianoforte

played by Sviatoslav Richter

and Marguerite Long (Vuillard).

Shit, piss and corruption:

did I or did I not

take my Placidyl, which is a sleeping pill …

The visionary serenity, which is indeed “simon-pure, the real thing,” first divagates into childlike silliness (“the nose flute / and the oot of instruments”), then descends to a profane interruption as Schuyler tries to remember whether he took his sleeping pill. “Shit, piss and corruption” comically matches “light / gentle and bright / light …” To the pure all things are pure, and in “O Sleepless Night” Schuyler convinces us of his purity: his cursing is a kid’s cursing, and his invocation of Lear (“Never, never, never, never” does he sleep under blankets, he says) is a transparent attempt to dodge the association of sleep with death. There is still mortality, the realm of corruption that heavenly angels, singing us to our rest along with the ethereally named Placidyl, make us forget. And as for the shit and the piss — Schuyler reminds us that, as Bernard of Clairvaux put it in his famous one-liner, we are born inter faeces et urinam. All this is transmuted into sweetness as, at the end of “O Sleepless Night,” flights of angels sing Schuyler’s beloved Tom to his rest: “Good night, sweet prince / And flights of angels sing thee to thy rest,” the poet murmurs. (Is Schuyler’s fantasy to be a Horatio: secure in his loyalty, glad to be of use?) Meanwhile, the sleepless poet has been taking “flights / of total recall,” remembering telephone numbers, zip codes, Leopardi’s verses. The last words of “O Sleepless Night,” after Horatio’s lines about dead Hamlet, are “Give me the Knife” — a quotation from Titus Andronicus. Titus, addled with grief, leaps about stabbing a dead fly, incensed because the insect is black and ill-favored like the villainous Aaron the Moor. It’s a ludicrous moment from Titus, Shakespeare’s gruesome, comic pastiche of Marlowe, and it offers Schuyler the dose of silliness he needs —better than any sleeping pill.

With his final Shakespearean phrases in quotation marks, Schuyler in “O Sleepless Night” evidently provides a miniparody of the ending of The Waste Land, and for good measure “Rhapsody on a Windy Night”: “sleep, prepare for life.’ // The last twist of the knife.” So he leavens his distress, and has his poke at Eliot’s high, portentous manner too. His nerves are bad tonight, and such a plight calls for a flippant moment, not a solemn Eliotic one.

Helen Vendler praised Schuyler as a tender and accurate pastoral poet, attuned to the enlivening details of landscape: a poet wistful, alone, and often enough strangely happy. She added, though, that his credo is “Let me in; let all of me in.” Schuyler’s insistence, matter of fact and all-important, on getting the whole man into the poem — warts and all, including the desperately nutty streak, the petty and obsessive ruminations, and the sour bursts of self-blame — has room too for the balloon of rapture, rising “beyond, way far beyond / all human comprehension.” He had his Paradiso as well as his hell; he knew as well as anyone how to be thankful for delight. And for that we are delighted, too — and thankful.

Edited by David Kaufmann