The visions and worlds of Hagiwara Sakutaro

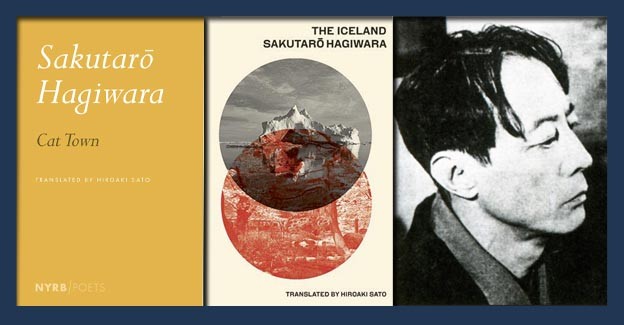

Cat Town

Cat Town

The Iceland

The Iceland

You may smash a fly but the fly’s “thing in itself” will not die. You’d simply have smashed the phenomenon called the fly. — Schopenhauer

So says the epigraph to Hagiwara Sakutaro’s “roman in the style of a prose poem,” Cat Town (1935) — in the eponymous volume which also includes his collections Howling at the Moon (1917) and Blue Cat (1923), as well as a selection of other poems. Cat Town itself is a confession of frayed nerves as the author wanders through the countryside and eventually discovers a town populated only by cats. In its final section he retells Zhuangzi’s butterfly dream, in which the difference between dream and reality is thought to be undecided, and ends by stating that somewhere in the universe that particular town of cats, the one he saw, certainly must exist. Like the Schopenhauer epigraph that begins his narrative, one is left asking if one’s “living perception can still recreate” in the imagination what may have been. The fly, like the town of cats, will always exist in its idea.

In his introduction to Cat Town, translator Hiroaki Sato notes that Hagiwara called himself “nearly blind” when he wrote, working off of “inspiration,” and that “the poetic theory he developed and expanded tended to narrow his scope.” This theory conceived of poetry as “any noticeable sentiment,” and that sentiment was expressed as “image”:

[T]he poet’s task was to express his subjective image as accurately as possible. Poetry was a ‘direct expression of music’ only when the poet succeeded in projecting his inner rhythm, namely, his vision. (xxxi–xxxii)

In his own introduction to Howling at the Moon, Hagiwara states that “rhythm cannot be explained,” and that “for someone to express his feelings completely is not something that can be done easily. In such a case words are useless. There are only music and poetry for that.” He also states that “[p]oetry is a language that goes beyond language.”

According to the translator, Hagiwara’s poem “Sickly Face at the Bottom of the Ground,” the first poem in Howling at the Moon, was completely new to Japanese circles at the time, introducing an indefinite subject through a relatively new, imported style — free verse. By disengaging from previous tropes, as well as adapting a style that appears to be a rejection of form, it seems to display both a highly particularized “inner vision” as well as a less determined language “beyond language.”

Sickly Face at the Bottom of the Ground

At the bottom of the ground a face emerging,

a lonely invalid’s face emerging

In the dark at the bottom of the ground,

soft vernal grass stalks beginning to flare,

rats’ nest beginning to flare,

and entangled with the nest,

innumerable hairs beginning to tremble,

time the winter solstice,

from the lonely sickly ground,

roots of thin blue bamboo beginning to grow,

beginning to grow,

and that, looking truly pathetic,

looking blurred,

looking truly, truly, pathetic

In the dark at the bottom of the ground,

a lonely invalid’s face emerging.

More complicated are his “war poems” that touch on or praise Japanese militarism and imperialism: “On the Day Nanking Fell,” a commissioned poem that the author was embarrassed over (and is only included in Sato’s introduction), “The Army,” and “The Naval Review Off Shinagawa,” in The Iceland. For the contemporary reader of political history, these poems leave perhaps more discomfort than poems like the above, despite their long-lasting influence on Japanese letters. One may ask whether these “political” poems fall short of, or actually fulfill, the prescriptions for poetry the author sets:

On the Day Nanking Fell

The year about to end,

the soldiers’ bayonets gleam white.

The army travel calendar past summer, fall,

Shanghai scaled last night 100, 1,000 kilometers away.

Our marching days have no rest,

men and horses vie to run ahead,

supplies continuing in mud-oozed roads.

Ah those fighting on this plain

vow never to return alive,

under helmets all sunburned.

Heaven cold, sun frozen

the year about to end,

Nanking here has fallen.

Raise our sun-bright flag,

Time for all to be relieved of anxieties,

our victory decided,

they should celebrate banzai.

They should shout banzai.

In tone the poem reads more like a dirge that borders on the satirical than a patriotic screed. Although he died before reports of the Rape of Nanjing would have reached him, had it been about any other event, or at least the celebration of free verse we see in his other “inspired” and seemingly ahistorical works, this poem would be easier to overlook. Today we often expect a certain “decency” out of poets who broach topics like military intervention, but it would seem that we need to suspend that expectation if reading a poem like this — if we want to get more from it than a sense of disgust.

So probably more interesting to ask, rather than where Hagiwara’s decency is, is how this poem ties together with his statements on “rhythm” and “vision” — his poetics, and if there is a broader philosophical inquiry taking place. As with the reimagining of the “cat town,” is there also an existence which exists outside of its phenomenon, like Schopenhauer’s fly? In other words, does it say something “beyond language,” something that it does not literally say?

Because of its compromised nature, it may be easier to make an argument for communicating “subjective image” more completely in “On the Day Nanking Fell” than in “Sickly Face at the Bottom of the Ground.” The tone, again, is hardly triumphant; the “banzai” at the end sounds weak and deflated. While no one wants to say something as simple as that a poem doesn't do what it says it will do (which in this case is to celebrate the Japanese victory in Nanjing), it appears that the sentiments in the poem express something other than what they purport to. One wonders what kind of message the poem is sending, and the obvious division between the ostensible subject matter and its delivery is what raises the question. One wonders about the meaning of it “beyond” what it says, but does not ask what it in fact does say. Nevertheless, this hardly answers the question of a precise correlation of subject and style.

Frustrated with free verse, Hagiwara made a “retreat” to writing (ironically enough) “Chinese-style poems” — Japanese poems written in imitation of Japanese translations of classical Chinese poetry. These poems, collected in his last manuscript The Iceland, by default loosely follow Tang-Song rules of prosody, incorporate Chinese syntax and terms, and formally seem over-dense and stiff when compared with his earlier poetry. But within the confines of a quasi-formal verse derivative of the Chinese masters, Hagiwara found that a “language for writing,” as opposed to the spoken vernacular he used previously, was better for expressing his “fierce emotions” that “scream” than the vernacular, which was better suited for a state of “lassitude.”

Calling The Iceland an “accurate written diary,” Hagiwara attempted to write poems that were meant to be read as a “visual language,” that the translator calls “terse” and “masculine,” in contrast to the “sinuous,” “feminine” vernacular Japanese. A “visual” language: the “Chinese-ness” is unspoken, but remains in the characters, and the poems are thus records of scopic collisions of the imagination, and not the “sinuous” persuasions of speech:

A Crow of Nihility

I was originally a crow of nihility

on that high roof of winter solstice I’ll open my mouth

and roar like a weathervane.

Whether the season has epistemology or not

what I do not have is everything.

The intrusion of technically philosophical language into an unspoken context can here be read against early poems, like “Sickly Face at the Bottom of the Ground,” in which the context is given no direct philosophical claims. Additionally, the “masculine,” “unspoken” quality of the poem is not, as in “On the Day Nanking Fell,” the semantic content or intent, but the lack of cohesion in the poem: the terse language does not persuade the reader. The “Chinese” language abuts the images it represents in their Japanese pronunciations, but instead of resolving itself through “sinewy,” mercurial speech, to this reader it has the opposite effect: the language alienates the reader further.

But this is only a “retreat” from the poetry of dialogue, and Hagiwara gives us a more uncompromising vision than before. It is the inability to present “everything,” the slick poem-as-narration-of-image that the author lacks, and it is only through the concrete untranslatability of an alien language that his feelings can be expressed. “Crow of “Nihility” is, strangely, a poem that combines the evocation of deepest feeling with the inability to say clearly what one is feeling exactly — not because Hagiwara is inarticulate, but because the truly resolute poem, to him, is itself fractured, and at odds with itself.

His poem “The Tiger,” in The Iceland, in my opinion gets closest to presenting the “language beyond language” and the reimagining of the thing that seems at the heart of Hagiwara’s project. Like the town populated by cats, we are given a literal image, but yet cannot imagine any correct context for which it exists. The “rhythm” of the poem is an embodiment of the contradictions of textual feeling — a “Chinese-style” poem with intermittent English vocabulary, and a vaguely industrial/commercial landscape pointing to the absurdities of modern life (“elevators,” in English). His Blakean tiger functions as an irreducible index: the tiger’s “afterimage” is a “total view of a void,” connoting again the impossibility of resolution, and the multiplication of possibilities — perhaps somewhere in “the universe.” Of course, it is impossible to prove one has been to a town full of cats, and it may not be true. However, if one perceives that town, or perceives a tiger on a roof of a department store, it may be a result of vision, rather than of a single obvious world.

Considering the uniqueness of these two volumes of Hagiwara’s, I’m disappointed that there has been (in America) so little discussion of either his poetics, or what may have been his politics — any discussion seems mostly limited to his style. To Hiroaki Sato’s credit, he has always addressed these two issues straightforwardly. At a recent celebration of the publication of Cat Town, he briefly addressed Hagiwara’s politics again — although none of the other participants did, and there were no questions from the audience regarding Hagiwara’s politics either. Perhaps “On the Day Nanking Fell” really is just a blip, or a mistake. Or perhaps it draws out more questions about the supposed limits of the imagination. In the spirit of Hagiwara, it may be our job to read poems against themselves, for what they actually say, and for their worlds of meaning.

The Tiger

It’s a tiger

wide and vague as a giant statue

you sleep in a cage in the uppermost floor of a department store

you are born no machine

you may tear apart and eat meat with your fang-teeth

but how can you know human reasoning?

Behold, under the orb sooty smoke flows

from the roofs of factory-zone town

sad whistles rise and spread.

It’s a tiger

It’s a tiger

It’s an afternoon

the ad-balloon* rises high

in twilight-close city sky

on this high-rise building sitting in the distance

you are as hungry as a flag.

When you scan vaguely

you make the worms crawling along the streets

your live food dark and depressing.

It’s a tiger

on the roof of prosperity in the midst of Tokyo City

where elevators* go up and down

wearing an amber striped fur

you suffer solitude like a wasteland.

It’s a tiger!

Ah it’s all your afterimage

a useless total view of a void.

— On the roof of Ginza Matsuzaka-ya

*terms in English in the original