Errant readings

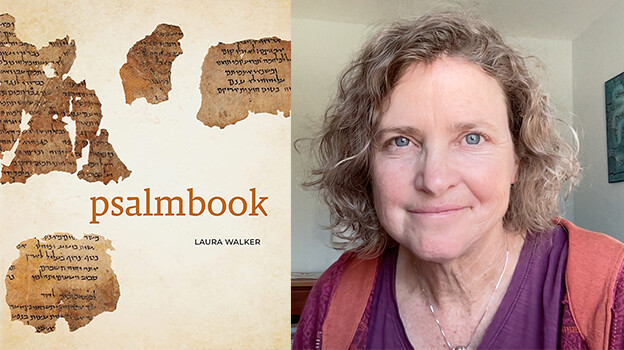

A review of psalmbook by Laura Walker

psalmbook

psalmbook

selah

In Laura Walker’s psalmbook, this word appears: first, large and lowercase, on the page where ordinarily you’d find a dedication, and then another three times in the book, including in the last poem.

According to Merriam Webster, the word is “a term of uncertain meaning found in the Hebrew text of the Psalms and Habakkuk carried over untranslated into some English versions.” Hypotheses abound: it could be a liturgical-musical mark, an instruction to “stop and listen,” a blessing meaning “forever,” an injunction to destroy bad people, or maybe an instruction to delete language that crept into a psalm and should be skipped. Some, including the authors of The Brown-Driver-Briggs Hebrew and English Lexicon, interpret it as “exalt.” Some, such as the folks at the evangelical Christian organization Soul Shepherding (and me, too, come to think of it), associate it with breath, as in taking a breath, a breather, a break, to pray.

Selah is the perfect opening, the perfect close, to a book that seeks meaning while simultaneously embracing radical uncertainty — a work that deliberately “gets it wrong” in order to create room for us to pause, listen, and breathe, to beseech, lament, and sing, alone and together, in all of our flawed, at times hurting and hurtful, humanity.

The poems in psalmbook respond to the King James Version (KJV) of the Old Testament book of Psalms (which is understood by contemporary scholars to have been composed by numerous authors over several centuries). In one sense, the poems call to mind translation: their titles are those of the psalms they engage. The multiple versions of some psalms also bring to mind translation, which can never be definitive.

But if this is a work of translation, it is so only in the loosest sense. The poems range in length from a full page to a single line (“psalm 85” reads in its entirety, “I remember you :”).[1] Stanzas are often short and seem to break off mid-thought, as if the lyric voice were suddenly overwhelmed, whether by doubt, confusion, or awe. While many of the poems unmistakably engage the content of the psalms they are named after, in other cases the connection is oblique in the extreme. The collection is presented in a nonnumerical order, and many psalms are missing entirely, further distancing the work from any sense of deference to the source. Walker responds as poet-seer — simultaneously inhabiting, reacting to, and renewing the biblical text — rather than as either scholar or religious devotee.

Yet despite these poems’ refusal of studiousness, they nevertheless function as their own form of close reading. Scrutinizing the choices made in the poems alongside the psalms that propelled them provides rich food for thought about the original psalms and their relation to our own time and takes us deep into reflection on the poet’s job.

On first encounter, the reader is immediately struck by the difference in diction between the two collections. Many, myself included, grew up under the spell of the KJV’s declamatory “thee”s and “thou”s. Psalms 5 begins:

Give ear to my words, O LORD, consider my meditation.

Hearken unto the voice of my cry, my King, and my God: for unto thee will I pray.

My voice shalt thou hear in the morning, O LORD; in the morning will I direct my prayer unto thee, and will look up.

Walker’s book is markedly and touchingly plainspoken — which, combined with a lack of capitalization and hints of an ordinary contemporary life, conveys both humility and accessibility. Walker’s “psalm 5” opens:

listen —

i will talk to you in the morning

by the washing machine (55)

The KJV psalms, which burst with urgency and emotion, mostly suggest a self beseeching and celebrating God, but at times they switch midstream to address the rest of us:

Deliver me not over unto the will of mine enemies: for false witnesses are risen up against me, and such as breathe out cruelty.

I had fainted, unless I had believed to see the goodness of the LORD in the land of the living.

Sometimes they shift personas as well, adopting the voice of the community or of God:

Some trust in chariots, and some in horses: but we will remember the name of the LORD our God.

I will instruct thee and teach thee in the way which thou shalt go: I will guide thee with mine eye.

Many of the poems in psalmbook unambiguously render the sense of a precarious “i” yearning for acceptance, deliverance, or even just contact with an elusive, and therefore powerful, other:

i stood outside your bedroom door,

could hear you,

something inside, could hear

the shifting of curtains (24)

But if the KJV psalms at times play fast and loose with pronouns, Walker does this infinitely more so. She leaps nimbly among identities, often within a single poem:

i know that you know

that i am not a horse and yet

i am a horse, a net, a fish in a net

and you find us

partial and confettied :

when the light hits the cedars

i hear them filter and break

and the sky i

they fell out of trees

i watch them return to their tents (33)

Is “you” God? The reader? A dimension of the speaker’s interior world? All of the above? “i” is not a horse and is a horse, a net, and a fish in net? And who is “us?” The aforementioned horse, net, fish? Humanity? Like the Old Testament psalms with their multiple perspectives and addressees and their enormous cast of characters — from “the enemy” to “the avenger”; from “ten thousands of people” to “the fowl of the air and the fish of the sea” — this book, too, includes a world of beings and speaks from various vantage points within that world, but the shifts happen more often. In doing so, the collection foregrounds the diversity and sense of community implicit in the psalms.

The inclusion of multiple poems in response to individual psalms provides additional clues as to Walker’s preoccupations. Compare the opening lines of two versions of “psalm 5” quoted above; in the first, the speaker confidently expects conversation; in the second, the speaker is hovering outside a shut door, seeking the slimmest signs of the remote other’s intentions. As different as these stances are, they both focus on the speaker’s shifting thoughts and feelings about relationality.

The confounding of pronouns, fragmentation of thought and image, and multiple responses evoke the space of daydreams and night dreams, where we (re)create and (re)configure roles and dynamics to make meaning of our lives, leaping between partially developed images and scenarios in the service of tracking barely perceived threads of thought and story:

a house floats upon the sea,

watery and unopened :

we fell a long way, salt to floors,

flags and years and out again :

open your mouth (30)

Yet such work is hardly cut off from the rest of the world. And the more acutely one attends to one’s environment, the more urgent issues find their way into what we frame as interior life. The challenge for the poet-seer of any epoch is to cultivate silence so that when they invite the noise in, they can manage to hold and shape it into an offering without complete overwhelm. In Walker’s case, shards of language placed within the space of the page might suggest the active work of the poet to juxtapose pieces of reality and thought in a mosaic that creates beauty and meaning from chaos. These shards may signify how close to the breaking point the poet may feel at times, how intensely she longs for deliverance from the suffering she is attempting to hold. They may suggest that in the work of spiritual seeking, the seeker at times enters a place — of doubt, confusion, or awe — that is beyond or beneath language. And the fragments can at the same time offer a generative refusal to pretend that either the organic flux of reality or the mess we’ve made of our world can be tidied up — generative because acknowledging the truth of how things are is what enables us to find a way forward.

The biblical psalms give plenty of prompts for forms of suffering to attend to. The God of the psalms is regularly petitioned to inflict brutal punishments upon the speaker’s many enemies and has his wont with the weather and the earth; the speaker yearns to enter God’s doorway as protection from the “tents of wickedness.” Walker’s errant readings expose the violence in the original text, producing poems that with Aikido-like dexterity evoke war, climate change, and houselessness while replacing rage with questions, observations, and compassion. So, in Psalms 144, the line:

Blessed be the LORD my strength, which teacheth my hands to war, and my fingers to fight:

morphs in Walker’s corresponding poem into:

my fingers break

when i am alone (29)

The same psalm’s lines:

Cast forth lightning, and scatter them: shoot out thine arrows, and destroy them.

Send thine hand from above; rid me, and deliver me out of great waters, from the hand of strange children;

become:

there is arrival below the storm :

water full of straightened children : (29)

And the psalm’s line:

that our sheep may bring forth thousands and ten thousands in our streets:

becomes:

sleep in their thousands crowding the streets (29)

To the extent that Walker does inhabit violence and divisiveness, she does so, it seems, to demonstrate that at times all and none of us can be the enemy — of each other and of ourselves:

a veined thing

rage

let us break their hands

and hobble ourselves toward water (34)

Reading Walker’s transformative engagements with the fire-and-brimstone psalms, we can’t help but reflect on how the Old Testament and other early, patriarchal texts helped shape the terms of the world we inhabit today, with its brutal binaries, repressive hierarchies, and environment crumbling under the weight of our abuse. We can’t help but think about all those in our time who turn to the Bible and other religious texts with a fundamentalist fervor that fuels terror and division — and then, with Walker’s help, to own our share in the perpetration of judgment and harm.

… And then, too, with Walker’s help, to sing praise to what or whomsoever we choose for getting to be here amidst the miracles of creation:

praise

sanctuary

praise

pewter

praise ice and trumpets

carp and salt

praise

internal organs and the rounding cymbals

high cymbals

far-sounding cymbals

praise (28)

Neither bowing to an almighty Father nor fully disavowing belief, this poem sings praise to the strange and specific paradise of life on our fragile planet. While few poems in the volume are solely dedicated, like this one, to celebration, we might on certain readings choose to view the entire book through this portal. The crafting of poetry is active participation in the creation that we all are — and even the poems that are cracking with pain are evidence of a poet plying her craft with dedication, love, and exquisite skill. Not unlike the anonymous authors of the lyrical and potent Old Testament psalms, she promises:

i will sing if you want me to, i will sing (29)

She does. We do. She will.

selah

[1] Laura Walker, psalmbook (Berkeley, CA: Apogee Press, 2022), 75.