Excavating intimacies

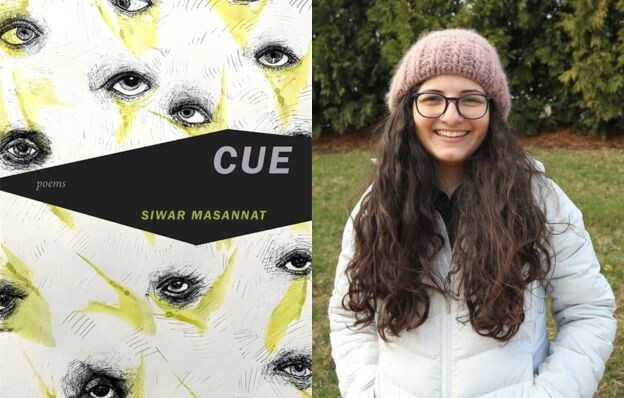

A review of Siwar Masannat’s ‘cue’

cue

Siwar Masannat

University of Georgia Press 2024, 82 pages, $19.95, ISBN 9780820365978

Siwar Masannat is a Jordanian writer, poet, educator, and editor currently based in Milwaukee.[1] cue, Masannat’s second book of poetry, emerges from her engagement with Akram Zaatari’s project Hashem El Madani: Studio Practices, part of the multi-year Madani Project. An archival and curatorial endeavor in collaboration with the Arab Image Foundation, the Madani Project brought El Madani’s compelling photographs of community members in Saida, Lebanon, to a global audience. Himself a photographer and filmmaker, Zaatari adopts an archival role in this project, carefully “compiling, structuring, and (re)contextualizing photographic material” from El Madani’s Studio Sherezade.[2] Featuring a diverse collage of same-sex couples, heteronormative family portraits, body builders, and an effeminate tailor, El Abed, the photographs offer an intimate glimpse into private worlds.[3] In the brief yet informative preface to cue, Masannat explains that “[e]xcavation as an artistic technique appears especially significant in Zaatari’s oeuvre, including his films,” and cue embarks on a similar journey of uncovering and revelation.[4]

Richly layered with images and verse, cue invites the reader to return again and again, an invitation I happily accepted several times over the course of a week. Although Masannat notes that portions of cue have been previously published as individual poems, the collection stylistically reads as one long poem (the eponymous “cue”) and one shorter poem, “a plan(e)t–” which closes the collection.[5] As I read and reread the slim volume, I repeatedly reveled in the delicate ambiguity of Masannat’s verse and El Madani’s starkly intimate photographs. It’s worth noting that the reproductions of the photographs in cue are an added delight, inviting further exploration beyond the page — I found myself plumbing the internet to discover more of Zaatari’s work and El Madani’s archive. Just as Zaatari once described working with El Madani’s archive as a process in which he “almost archaeologically” took stock of both photographs and workspace, reading cue feels like a gentle brushing away of sand, dust, and time that consistently reveals new treasures.[6] While the collection’s germinal connection to Zaatari and El Madani begs a consideration of the archive, the image, and historical memory, cue yields layers of inquiry and meaning. The public and private, the question of memory, multispecies kinship, and the capacity of language to transmit emotion across time and space all percolate amidst its pages.

Masannat at times directly quotes Tarek El-Ariss, Emily Dickinson, Joy Harjo, Etel Adnan, and Lorine Niedecker in cue, which, like photography, archival work, and Studio Practices, is similarly a work of exposure, transfer, and excavation. Poetically resisting the dualistic classifications of public and private, male and female, human and nonhuman, cue, like El Madani’s photographs, offers a glimpse into the networks of intimacies and relationships that exceed the classifications of gender, species, geography, and language. Formal layering of folk tales, erasure poems, photographs, Arabic, and English in Masannat’s delicate, resonant verse generates a rich, textured book of poetry. The textured paint streaks erasing Michel Foucault’s The Order of Things, which appear at intervals throughout the text, further work against the concept of classification, boundary, and separation. Textured and nuanced, cue’s layers invite a gentle excavation, through which one may discover the fraught intimacies and tenuous connections between seemingly disparate spheres.

Writing about cue without considering Zaatari’s work feels remiss; cue is one of several artistic and scholarly responses emerging in response to Studio Practices. Masannat devotes a paragraph of the preface to acknowledge past engagement with Zaatari’s oeuvre, noting Gayatri Gopinath, Chad Elias, and Tarek El-Ariss, who, like Zaatari and Masannat in turn, take “an approach of excavation and layering.”[7] In “Queer Visual Excavations: Akram Zaatari, Hashem El Madani, and the Reframing of History in Lebanon,” Gopinath describes Zaatari’s work as productive of an “alternative optic” that “renders apparent the unruly embodiments and desires that are usually obscured by dominant historical narratives.”[8] Another article, also by Gopinath, describes El Madani’s photos as “visions of gender nonconformity and homosocial intimacy that marked this ‘othered’ space of the region of southern Lebanon.”[9] For Gopinath, the photos “speak to a quotidian strategies of self-representation by which non-normative subjects envision a sense of place and emplacement,” alerting the viewer to the complexities of identity and belonging constellating in El Madani’s Saida.[10] Layering normative and non-normative subjects together in a visual record of the diversity and vibrancy of everyday life, El Madani’s archive provides a counternarrative to what Masannat describes as “the respectability politics of the moment.”[11] Through Zaatari’s artistic excavation, alternative ways of being emerge, and we in turn view Saida’s past in a different light.

A work of excavation is perhaps inevitably one of desire — the desire to uncover something, to gain intimacy, or to possess knowledge — and desire consequently proliferates throughout the pages of cue, constellating in the photographs and accumulating outwards in layers. First, there is the subject’s original desire to be photographed, the desire between the subjects in the photographs, and ostensibly the desire of the photographer, who may have cued the scene with specific choreographic instructions:

tarek el-ariss traces the gazes of those photographed to reveal the hidden hand

of el madani in arranging the scene. he points to the desire of the choreographer

to see another in a pose – to taste pleasure in the approach, a sincere incline here

and another’s pursed lips. could the choreographer be an excavator too of the

subject’s playful desires?[12]

One wonders if the poet and the reader similarly become excavators of this playful desire, as we imagine the context of the image and wonder at the interiority of the subject captured fleetingly on film.

Like poetry, photographs allow for the transmission of scenes, memories, and emotions from one time or place to another. In the case of El Madani’s studio portraits, the images offer a point of access to a private life that existed outside the more conservative social practices of the period in which he worked. Yet as present-day viewers of these images, our own desires, memories, and emotions torque the weight of the image and mediate our intimacy with El Madani’s subjects. Masannat’s reading of the first El Madani photograph[13] featured in the collection, in which two men pose for a wedding portrait, elucidates the photograph’s transmission of feeling:

whereas asmar here is the true melancholy center of the photograph–star of a

delicate, plastic flowering–najm’s soft lean into him as tender as i recollect

your hands: gentle, warm–generous on my knee.[14]

The desire and tenderness captured in the frame travel and transform, resonating with the poet speaker in another moment of love, longing, and tenderness. Beyond its ability to conjure emotions in the viewer and relate the moment of the image to the present day, the photograph offers a tenuous intimacy with the past, cultivated through shared emotion.

While the photographs are revelatory, they demand a level of speculation and extrapolation — a sort of imaginative excavation. This is perhaps most clear in Masannat’s poetic response to Ahmad El Abed, the “‘effeminate tailor’”[15] in El Madani’s photographs.[16] In over one page of verse, they wonder at what the photographs of El Abed leave unsaid:[17]

is that your lover / was he as honey did he / steal a kiss on your cheek as you sewed flowers / on his lapel, that lace trim kerchief spilling from his chest / pocket i must confess i am searching for that sugary playfulness[18]

This search is perhaps a form of desire in itself — the desire for intimacy and recognition.

The “natural” is another site of excavation in cue, which like the subjects in El Madani’s photographs, becomes at once familiar and partially unknown. Challenging the human/nature binary, Masannat swiftly reminds the reader that photography, although technologic in its ability to capture, store, and transmit particular moments through film and apparatus, is an inherently natural phenomenon. If photography appears as a human technology, it ultimately belongs to the sun:

he was asked once: your son is practicing photography. isn’t it a sin?

he said: when one stands near a pool of water and sees one’s reflection in it, this is photography. there is no harm in it.

this is not a sin. this is a transfer of an image.[19]

Plants and animals proliferate throughout cue to further reconsider the human/nature divide.Without romanticizing our nonhuman kin, Masannat elaborates on their networks and alliances, from which violence (“bleeding chicken chased by / rest of chickens pecking her eating from her flesh until she dies”[20]), multispecies care (“peahens might leave their eggs for chicken hens to incubate”[21]), love (“share food groom lick their kin / and friends”[22]) and potential (“human scientists are working hard to explain the / spontaneous biological capacity of some chickens to alter sex”[23]) emerge. A bird’s accidental flight into a window becomes a revelation of shared rhythms:

a bird hits my window, i turn

and my heart for a second stops,

breath delayed at nostril.

muscle and valve will yield

to a common beat once

i hear flapping, glimpse flight

again as glass settles to still.

to love is an entire age of such

rhythm. inventory of vulnerability,

relentless.[24]

Later, chickens and humans grow alike through their habits and comportment:

like people chickens climb and descend

ranks, consort, switch

and flip and flap and extend

flightless wings. like

people, they get

occasionally peckish.[25]

Through the quiet excavation of our shared loves, violence, and irritations, Masannat encourages us to perceive the natural world as something strange but intimate, a place in which we recognize ourselves reflected among our myriad relations.

Chickens are also significant to cue for their domestic nature; as Masannat reminds us, they “were first invented as farmable and companionable.”[26] Residing in yards and gardens, chickens are part of a private, domestic world of food, gardening, chores, and love, a world Masannat, like El Madani, gently brings to the surface through series of poetic descriptions that pulse with memories, small snapshots into moments past:

and me, my child tea, my uncle

his coffee

and we greet every

day so before most others[27]

However, the private in cue is not without its own layers — layers of desire and longing that emerge within homes or relationships, sometimes uncovered and sometimes held inside. Fingers link under tables surreptitiously, love for a woman’s chuckling laugh remains unexpressed, and women chart their way “between / gossip and memory” in a home of shared households, “one building of overlapping circles.”[28] Gently unveiling the complexities and nuances of private life, Masannat’s spare verse invites the reader to wonder about words left unsaid and desires unexpressed. Their delicate, poetic snapshots of homes, loves, and kitchen tables nurture a sense of intimacy and distance that El Madani’s photos similarly cultivate.

This delicate, tenuous yet tender intimacy reverberates throughout cue, like “an orchid’s spike: // its roots aerial,” grasping for contact and connection through air, across species, and through time.[29] Just as El Madani’s photographs ask us to pause and reconsider the lives and histories of subjects unknown to us, cue cues us to gently excavate our own lives and intimacies, reaching out with love and curiousity to wonder at what remains unsaid, “to reach for the orchid’s root, its gesture to spiral out.”[30] In our own readerly excavation of Masannat’s careful verse, we may find ourselves stretching towards old memories and strange intimacies that move, like images, words, or an orchid’s root — tenuously and unpredictably between bodies, a resonant desire always reaching out, revealing itself in flights of delicate beauty.

[1] Siwar Masannat, “About,” Siwar Masannat, accessed 29 July 2024, https://siwarmasannat.com/about/.

[2] Belinda Grace Gardner, “Akram Zaatari: Objects of Study,” Bidoun, no. 10, Spring 2007, https://www.bidoun.org/articles/akram-zaatari.

[3] Some glimpses into El Madani’s collection, as part of Akram Zaatari’s Hashem El Madani: Studio Practices, are available online. See the Sfeir-Semler Gallery website https://www.sfeir-semler.com/%09hashem-el-madani-studio-practices-2006 or the Tate Modern’s website https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/zaatari-objects-of-studythe-archive-of-studio-shehrazadehashem-el-madanistudio-practices-101040/4. Although the Arab Image Foundation does not display Zaatari’s collection of El Madani’s work online, they offer a beautiful collection of digitized albums for viewing, which offer an equally intimate insight into daily life in Lebanon, Palestine, Iraq, Syria, Egypt, and Morocco: https://arabimagefoundation.org/albums/.

[4] Siwar Masannat, cue. (Athens, Georgia: University of Georgia Press, 2024), vii.

[5] Masannat, cue, 85.

[6] Akram Zaatari, “Objects of study / The archive of Shehrazade / Hashem El Madani,” Sfeir-Semler Gallery, 29 July 2024, https://www.sfeir-semler.com/galleryartists/akram-zaatari/work?page=10.

[7] Masannat, cue, vii.

[8] Gayatri Gopinath, “Queer Visual Excavations: Akram Zaatari, Hashem El Madani, and the Reframing of History in Lebanon.” Journal of Middle East Women’s Studies 13, no. 2 (July 2017): 328, https://doi-org.proxy3.library.mcgill.ca/10.1215/15525864-3861400.

[9] Gayatri Gopinath, “Hashem El Madani: The Studio Portraits: Envisioning Otherwise,” Tribe Photo Magazine: Photography & Moving Image from the Arab World, no. 5 (2017), https://www.tribephotomagazine.com/issue-05/blog-post-title-one-wya5n.

[10] Gayatri Gopinath, “Hashem El Madani: The Studio Portraits: Envisioning Otherwise.”

[11] Masannat, cue, vii.

[12] Masannat, cue, 10.

[13] Hashem El Madani, Najm (left) and Asmar (right), 1950s, silver print, 29 x 19 cm, Studio Shehrazade, Lebanon, https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/zaatari-najm-left-and-asmar-right-studio-shehrazade-saida-lebanon-1950s-hashem-el-madani-p79496. Note that although this photograph was displayed as part of Akram Zaatari’s project Hashem El Madani: Studio Practices, I cite El Madani as the original photographer here and in all subsequent photographic citations.

[14] Masannat, cue, 5.

[15] Masannat, cue, 14.

[16] Hashem El Madani, Ahmad el Abed, a tailor, 1948-53, silver print, 289 x 191 mm, Madani’s parents’ home, the studio, Saida, Lebanon, https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/zaatari-ahmad-el-abed-a-tailor-madanis-parents-home-the-studio-saida-lebanon-1948-53-p79484.

[17] Hashem El Madani, Ahmad el Abed, and his friend Rajab Arna’out, 1948-53, silver print, 289 x 191 mm, Madani’s parents’ home, the studio, Saida, Lebanon, https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/zaatari-ahmad-el-abed-a-tailor-madanis-parents-home-the-studio-saida-lebanon-1948-53-p79484.

[18] Masannat, cue, 14. Note that in the printed edition, Masannat employs the “ / ” to differentiate between line breaks, and nests the verse around two photographs of El Abed.

[19] Masannat, cue, 4. Note that in the printed edition. “there is no harm in it” is on its own line. The formatting of this document did not allow for an exact replica.

[20] Masannat, cue, 35.

[21] Masannat, cue, 32.

[22] Masannat, cue, 35.

[23] Masannat, cue, 21.

[24] Masannat, cue, 8.

[25] Masannat, cue, 27.

[26] Masannat, cue, 21.

[27] Masannat, cue, 18.

[28] Masannat, cue 22.

[29] Masannat, cue, 59.

[30] Masannat, cue, 81.