Between the Devil and God

Li Zhimin’s 'Zhongalish'

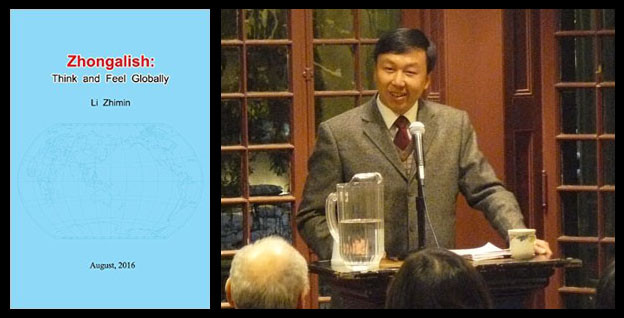

Zhongalish: Think and Feel Globally

Zhongalish: Think and Feel Globally

Best known in China for his translations of J. H. Prynne into Chinese, poet and scholar Li Zhimin is known in the US primarily as a fixture at Chinese American Association of Poetry and Poetics conferences and as an editor of the poetics journal Espians. In his English-language book of poems, Zhongalish: Think and Feel Globally, Li continues his cross-cultural work by exploring the lyric subject as a linguistic construct, as well as examining the mutual influence of Chinese and American “avant” poetry practices generally. Even the neologism “Zhongalish” is a combination of Zhongguo — the Mandarin term for China — and “English.”

Among the American academics who know Li’s work are a number of poets and scholars affiliated with Language writing who have made numerous trips to China and engaged with scholars there — this is immediately evident from blurbs by Marjorie Perloff and Charles Bernstein on the back cover of the book. In fact, Zhongalish can be read as the work of a poet in dialogue with Language methods at the same time that it investigates larger questions of mutual Chinese and US poetic influences.

What Li borrows from the Language writers is a playfulness with language that’s more disarming than confrontational or self-righteous — attitudes rightly or wrongly most often associated with the Language writers. Whether writing of having dinner with critic Marjorie Perloff (“Feel Words: One Way to Approach Language”) or listing his various friends named Charles (“Charles, my friend of lollypops”), Li is primarily concerned with China and the US as competing cultures literally speaking different languages.

For example, in the poem “Non-Presence,” which “is produced by the method of deletion,”[1] Li uses Language-style methods (the details of which Li leaves ambiguous) in order to write a conversational poem that takes a comparative approach to poetics. In it, Wordsworth and the Chinese philosopher Zhuangzi are anchored by the speaker’s departure from his mother tongue.

‘I will come back’

I tell my parents

A beautiful cloud is wandering

Lonely in the sky.

A leaf falls to its root.

Zhuangzi wakes up without knowing

Whether he is a butterfly

Dreaming to be a man

Or a man having dreamed to be a butterfly (43–44)

Compared to much Language writing, “Non-Presence” puts issues of the narrator’s identity, and relationships, front and center. A frequent strategy for Language writers in the ’70s and ’80s, developed from the modernist literary theories of Viktor Shklovsky and others, was formal experimentation in which linguistic and cultural critique was implicit. Li, however, lets his poems’ straightforward — and at times naïve — form carry semantic content, as though the poems were a conversation with themselves.

As such, a reading of “Non-Presence” could go like this: the speaker claims his intention to return to his parents, who are the recipients of his verbal expression. He also implicitly identifies as the isolated poet of Wordsworth’s famous poem, who, like a cloud, floats high above quotidian life.

Because of the inclusion in the second stanza of “a leaf falls to its root,” the Wordsworthian poet is forced into a thematic relationship with a leaf that falls to the ground, where the tree’s root is located, when it dies. Similar to the leaf, the poet will also return to its roots when he “dies” — when he fails to achieve the transcendence of the cloud.

But, like Zhuangzi, the poet is now unable to distinguish from whence he came. Did he go forth from his parents to independence, only to fall back to them? Or was his fall from transcendence a temporary failure, from which he will recover? Similarly, the poet, in departing from his parents, departs from his mother tongue to the language of the isolated Wordsworthian poet: English, the language of the speaker. Which is his “real” language? In this manner the text mirrors how Zhuangzi cannot distinguish between the waking and dreaming state.

Where the indeterminate or aleatory aspects of much Language Poetry are located in forms of “deletion,” or in devices like hypotactic sentences — in which the meaning of each discrete sentence is contingent upon surrounding sentences — the indecision of Li’s poem is perceptual. This sets him apart from the materialist poetics of much Language writing, for example in works like Ron Silliman’s Tjanting or Lyn Hejinian’s My Life, both of which use numerical devices to delimit what text is permissible according to their schema. In those works, the emphasis is on the internal structure of the work.

In contrast to the Language writers of the 1980s, who were fine-tuning theories of ideological critique and methodology, a generation of poets in China was shocking people with impassioned and unheard-of language that rejected the ideological discourse used to attack supposed enemies of the state. The anthemic poem by Chinese poet Bei Dao, “The Answer,” well known in its time, embodies this mode:

Let me tell you, world,

I — do — not — believe!

If a thousand challengers lie beneath your feet,

Count me as number thousand and one.

I don’t believe the sky is blue;

I don’t believe in thunder’s echoes;

I don’t believe that dreams are false;

I don’t believe that death has no revenge.[2]

As in “Non-Presence,” “The Answer” stands against certainty. Where “Non-Presence” reduces or “deletes” the subject as a source of knowledge and control, “The Answer” locates the subject as a negation of positive qualities. The way it’s written doesn’t express ideological critique through complex methodology — it simply uses the language of renunciation in order to demonstrate defiance.

In his “Epilogue” to Zhongalish Li inverts the renunciatory language of Bei Dao’s poem. Instead of disbelief in common facts, he chooses belief in a more complex reality than what’s commonly offered by either political or religious discourse.

I believe all books were written by human beings

I believe there is an angel and a devil in any human

I believe human beings see only what their eyes could reach

and know only what their age lets them know

I believe there is no book that is divine (78)

Newcomers to Li’s poetry (which will be most of us in English-language poetry circles) will be struck by how reasonable Li’s language is — he almost sounds like an Enlightenment writer, foreclosing against irrational statements like “death has revenge.” There is no heroic language, methodology, or notion of poetic rigor or purity. If anything, the tone is collegial.

That said, Li’s concept of “Zhongalish” connotes learned states of speaking, and as such he seems unconcerned with definitive, abstract statements about poetry. For Li, the speaking subject appears to take on cultural habits from whatever language they use, the result being an impure language and culture. Thus he can write that “When Ezra Pound wrote some “ungrammatical” English … he was writing Zhongalishly” (5). For Pound, if what Li says is correct, the loosening of English grammar was also the beginning of a non-American cultural identity.

But this also presents a problem. Li discusses learning a second language over and over throughout the book — it could pass as his main trope. Accompanying second language acquisition are of course linguistic and social foibles, as well as racist terminology that is disarmed by the fact that it’s yanked out of its social context. In such a case, Li tries to normalize language by culturally “translating” it — in which case cultures remain in place, even if they are rendered unexceptional.

Once we came across the word “Chink” at college

We did not know it and checked it up

in an English-Chinese dictionary

We got the meaning there

[…]

And a naughty boy told our English teacher:

we have something equal in Chinese for you too

it is Yangguizi / jaŋguizi / 洋鬼子

Our English teacher laughed and practiced his Chinese

woshi yige Yangguizi

We all burst into laughter (13–14)

As someone who taught English in China, I can only sympathize with the teacher here: faced with linguistic racism in English, it’s only appropriate to laugh it off when the Chinese near-equivalent is shown to be the translation of one culture’s concept into another’s, in which sender and receiver switch roles. Really, what else can you say but wo shi yige yangguizi (“I am a foreign devil”)?

This episode of course reads as one of a number of humorous and embarrassing moments in language study and pedagogy, but also suggests the simultaneous irreconcilability and universality of semantic concepts. As such, this may be where Pound is most relevant for Li, as well as for contemporary American readers: caught in between cultural concepts, Pound’s poetry both reveals his own cultural prejudices as well as thwarts them. Li, like Pound, is now neither a pure Chinese speaker nor a pure English speaker: “I am proud of being a Zhongalish … I live and die / A Zhongalish” (9). His lines are remarkable for correlating the notion of speaking a language with culture as well as nationality.

In Chinese, the term Zhongguo does not necessarily connote an ethnic group or dialectal language, but is more often a political designation. On the other hand, Zhongwen, a general term for the Chinese language, implies a tie to the nation by virtue of location in zhong, “the center.” Li’s Zhongalish-ness, or compromised Chinese-ness, appears to rest in the ability to slip out of speaking Chinese.

But perhaps a look at foundational concepts will help clarify this somewhat. In “Meeting Emily Dickinson,” Li writes of the God who dominated Emily Dickinson’s world, and of the difficulty he had overcoming his lack of belief in order to embrace the poet. In answer to that difficulty, in his “Epilogue” he dislocates the concept of “God” by translating it into a Chinese term, tian. Historically, tian sometimes connoted fate, sometimes the heavens, sometimes a panoply of deities, and sometimes just the sky — and the latter is how the term is most often used today. As “God,” tian sounds more like the Dao that Zhuangzi, Laozi, and other ancient thinkers speak of: apparent yet mysterious, full of potential yet empty.

I believe in God

I believe God would never speak to any human being

I believe human beings could never truly understand God

In fact, I prefer the term Tian to the name of God

[…]

Tian has the most beauty

Yet Tian never speaks

Tian has all the truth

Yet Tian never reveals it to anybody (79)

Here Li negotiates semantically between languages, but more importantly negotiates ontological meaning. Whereas “God” is the name for a concept, that name is subject to change and interpretation since “God would never speak to any human being” and tell its name. And since “human beings could never truly understand God,” there is no identity which warrants so precise a name in any case — if anything, a name that “has all the truth” but “never reveals it” could be said to be better described as tian, the historical concept: fate, heavens, gods, empty sky.

However, when describing this foundational reasoning — what is tantamount to a creation myth — both geography and the national constraints of language fall short of describing either personal belief in God/tian, or what happens in translation between languages. Furthermore, if one cannot be Christian without God, then, following Li’s thinking, one cannot be Chinese without tian. When Li does evoke tian, it is only a tenuous placeholder accommodating an ahistorical God — hence the hybrid identity Zhongalish. The Zhongalish is neither here nor there, and the origin of the Zhongalish is rendered indeterminate.

And so here is where it is important to note that Zhongalish: Think and Feel Globally is indeed a global and historical book of poetry. It’s about negotiating meaning as it is relayed from time to time and place to place. It’s only ironic that a poet like Li Zhimin is able to emerge as such a unique and strong voice by noting all of the compromises he must make in his language and his nationality — in short, his identity.

1. Li Zhimin, Zhongalish: Think and Feel Globally (Philadelphia: Chinese American Association of Poetry and Poetics, 2016), 44. [EPC Digital Edition: free pdf]

2. Bei Dao, The August Sleepwalker, trans. Bonnie McDougal (New York: New Directions, 2001), 33.