Uncurling

A review of ‘Fetal Position’

Fetal Position

Fetal Position

When I was a baby adult and even broker than I am now, I participated for pay in a study at a university that involved lying in a creaky old MRI machine, hooked up to two dozen electrodes that monitored my brain and systematically inflicted pain on my arms. My task was to look, via a tiny mirror, at a screen that displayed a blue square, then a red circle, then a blue circle, then a red square, or whatever, while the scientists applied a particular intensity of punishment as an accompaniment to each. I lay on my back contentedly and “rated” how much it hurt on a scale of one to ten. They never told me what was being studied. Soon, I got bored and started trying (via “unimpressed” ratings) to bait the scientists brattily into giving me harder and harder hits. In the end, I thought maybe I’d beaten them in a battle of wills, but in retrospect, I probably hadn’t. In between individual rounds of torture, you see, they beamed soothing audio and video of David Attenborough (talking about birds) into my electromagnetic womb. I turned into their creature. By the end, I thought circles and squares really do somehow signify, intrinsically, “ow.” I’m telling you all this because when I read Holly Melgard’s Poems for Baby trilogy (self-published, 2011), I suddenly remembered my MRI-machine experience for the first time in a decade. Frankly, whatever the study was, I can only assume Melgard was setting out to do something similar. Perhaps this should be investigated?

Seriously! Poems for Baby was a brilliantly sinister attempt to rewire semiotics — but for what occult purpose, as I say, one can only speculate. The trilogy pretends, you understand, to be a series of perfectly innocent and functional picture books. Only, each book bears the same line drawing of a particular shape on all its pages above a different unique word on each page, printed in a giant font. The voltage ramps up imperceptibly. Colors for Baby (the first book in the trilogy, which one orders off the print-to-order website Lulu.com) doesn’t contain any names of colors at all, which is why I asked for my money back, to no avail. The shape is a square: “window / snow / sweat.”[1] Next up, in volume two, Foods for Baby, the shape is a circle: “breast / melon / melon ball / dinner roll.”[2] Finally, in Shapes for Baby, the shape is not even really a shape: it’s a kind of backslash. Hardly any of the words are baby words anymore, at this stage. Almost none would appear in a conventional dictionary for two-year-olds. Come on: “descend / deplete / decrease / decline?”[3]

Reading the entirety of the trilogy out loud at an online event in January 2022 — which took less than four minutes — the poet held up the volumes for the audience one by one as she turned the pages. “Milk / glue / water / steam,” Melgard intoned, slowly exclaiming each item with the brightness of a preschool teacher.[4] Then came the circles: “cherry / tomato / cherry tomato.”[5] And finally, the sloped lines: “penis / crevice / crevasse.”[6] I cannot stress this enough: Melgard seemed to be giving a pedagogical presentation but was actually practicing regression hypnotism. Again and again, she turned her gaze back and forth, from page to camera. She turned us all into Baby.

Does Holly Melgard want to abolish adulthood? According to the hilarious video-commercial reel she put together with her friends, she’s been hoping to “automate” production of Poems for Baby — using children. “Let’s fill this void together,” she proposes cheerily in the video, applying a sticky note to the cover of Colors for Baby so that it reads Colors BY Baby instead. Having noticed that toddlers everywhere were treating her poetry collection (when it was present in their households) as coloring books, Melgard wisely capitalized on the phenomenon. In the ad, she enjoins us all to purchase the book (printed to order at Lulu.com) and read it aloud to a very young person. Then, we are instructed to provide pen and painting supplies and simply step back before photographing (and sending, in attachment, to colorsBYbaby@gmail.com) the results of the infant-in-question’s irrepressible compulsion to illustrate the black-and-white voids of the printed Poems.

The result, of course, is a crazy-making acceleration of language’s already everywhere-evident decline. Picture it: a box labeled “salt” containing a neon orange cow. Overleaf, a box labeled “clean” containing a horrible, turd-like fuchsia squiggle. Where will this end? The kids, enabled by Melgard, could tear down everything we think we know.

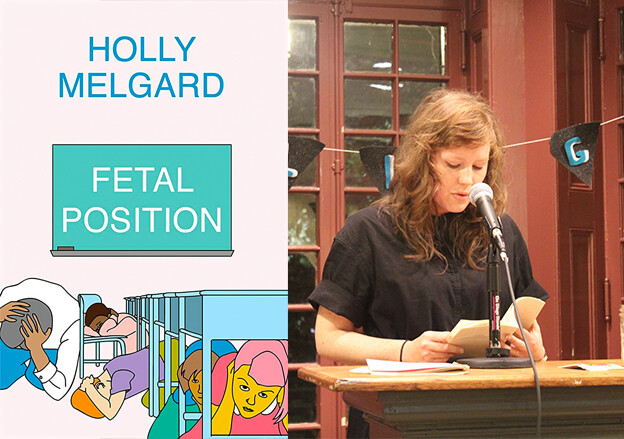

Imagine, then, my trepidation upon approaching Melgard’s new full-length book of poetry, Fetal Position, written exactly ten years later and ostensibly — but wait, I won’t be fooled a second time so easily — for adults. On initial inspection, things do seem promising: Fetal Position (2021) is published by the Segue Foundation (Roof Books) and distributed by Small Press Distribution, so there’s no print-to-order-online or child-labor element detectable. Furthermore, the third poem listed in the table of contents is labeled “Child Labor,” suggesting, perhaps, a newfound willingness on Melgard’s part to be serious about such human rights violations. Best of all, there are no brain-warping pictures in this one: I see no pictures at all, apart from the school classroom active shooter drill situation pictured in cartoon form on the cover. Otherwise unmolested by illustrations, all the words inside the book appear, at first glance, to fit normally into coherent semiotic chains referencing an established world most anglophone people would agree upon. In addition, most of the poems come with a reassuringly grown-up epigram by someone like Giorgio Agamben, Friedrich Nietzsche, or Silvia Federici. This time, I’m not going to be told mayonnaise is the same shape as ash. I’m going to be educated honestly (no doubt the cover is there to evoke the need for gun control to preserve the sacredness of our nation’s public schools). I breathe a sigh of relief.

I sit down with my partner and begin reading aloud to her from Fetal Position’s first poem, “Reproductive Labor”:

People keep asking me if I want kids, and I don’t know how to answer that question. I suspect I might want kids but I don’t know if I want kids, because I don’t know what wanting kids is supposed to feel like. I’m pretty sure I want to have had kids — you know, in retrospect — only because I don’t want to feel like I missed out on anything. But is that what wanting a child feels like?[7]

Hell yeah, this seems fun and relatable and interesting, we think, like an essay or an intelligent bit of stand-up or something. I keep going. “Does looking at a baby make your womb throb; your sperm squirm; your wallet pulse?” (11). Melgard asks, further down the same page. “I don’t know. You tell me.” More giggles. “At a certain point, will I get hangry for a child to fill up my midsection if I wait too long?” Ha! We have relaxed. Little do we know that the poem is about to stretch over ten pages and ask its question a hundred-odd different ways with the relentlessness of Socrates — or of a toddler — until we’re gibbering and disoriented. Already by the fifth page, in fact, my partner’s initially nervous laughter has lapsed into hysterical twitching.

“Does wanting a kid feel like the desire to serve another? […] it seems like there can be pleasure in that” (14). “Or is the feeling of wanting children more like the feeling of wanting to create a world in which others admire you, fear and respect you? […] Because I would be down for that — I never not want that, to be honest” (15). “I’m going to be pissed if no one cries when I die. Is wanting children similar to wanting to make people cry? That sounds kind of awful” (16). The litany rolls on. “Is it like, ‘you people all suck. I’m gonna go make my own people now.’ Like at a certain point, you just have to make your own people because all the ones you didn’t make are just too obnoxiously not your own” (18). Yes. Yes. The incantatory quality of the repetition becomes tortuous, yet it feels mesmeric, inescapable. None of the answers to the poem’s questions are “no.” “Is wanting kids a world-building thing or world ending thing?” (18). Yes. “What is the difference between wanting a kid and wishing the end of the world on someone at this point?” (19). Hard saying. And on and on. Then, the brakes suddenly screech: “I don’t feel strongly like I do or don’t want kids,” Melgard declares flatly — as though the past nine pages of racked ambivalence hadn’t just happened — “but I will never turn down the chance to enjoy a good miniature” (20). She’s pulled back now, all smiles, and she is chatting about nursery colors, miniatureness, dioramas. Maybe you’ve just let your breath back out when she whirls back around and delivers the coup de grâce. “Are children just toy people?” asks her final, deathly nonchalant line. “That could be fun” (21).

Melgard is as dexterous a defamiliarizer of heterosexual culture, especially patriarchal motherhood, as I’ve ever seen. If you thought “Reproductive Labor” was uncomfortable, you’ll need to be firmly seated before attempting the third poem, “Child Labor,” which self-describes as “Pornographic descriptions of what it feels like to be inside of a woman cut-up and re-ordered to form a composite narration of vaginal childbirth from the fetal point of view” (37). Here, the voice of His Majesty the Fetus — in the process of being birthed — fuses with the voice of a cisheterosexual masculine voice whose member the woman is sexually circluding. Both composite speakers are “balls deep in her,” “All of me was inside her,” “covered in her,” “I felt so big compared to her soft walls,” and more (40). Incestuously, as a result of Melgard’s exercise, parturition and copulation end up receiving the same subtitles, without loss of meaning: “‘She started begging me to go down’ ‘all the way’” (42); “‘But, when I went to enter her pussy just a little bit, she started screaming because it hurt too much’” (42); “‘Eventually, I stopped trying to not make her bleed and just went for it!’” (43). We are skating close, in this poem, to the sharply sex-dichotomous cultural-feminist view (sometimes cultivated by ’80s cissexist lesbian separatists) that maleness — even in fetal form — rips and tears women up, invades, consumes, and uses them. However, Melgard’s insistence on the mixture of noble and ignoble gestures, rapacity and comradeliness, in all people has been well established.

In the last two poems in Fetal Position, Melgard returns to the theme of parental appetite for “baby” but via the disconcerting route of cat jokes that get unexpectedly deep. “Catcall,” the final poem in the collection, consists of a mind-numbingly long and repetitive call to a presumed cat, a “little guy,” a “cutie,” a “huge cute little guy” (83–84) — a chant that slowly, inexorably, starts to evoke elements of rapacious egotism that coexist, possibly always, within maternal desire, alongside affection and respect.

Hey mister guy. Yeah you, I’m talking to you. You are going to be in my arms now because it is where you belong. Don’t you walk away from me. You need to stop being so far away from my body. Come on bud, give me your bod! There’s no point in fighting it ’cause I’m gonna have you now, ok? Oh, come on don’t give me that. Come on!

God damn this selfish guy. God damn him! Fuck his babybody for real.

Excuse me sir. Sir? Hey mister. Hey mister sir. Over here. I’m right here. I need your butt. Give me your butt. […] I’d like to bother your butt.

What the fuck. Why is he like that? I mean, look at that butt. I totally want to cup his butt right now. That’s what I want to do. Yeah, I want to do that to him now. (100–01)

This sadism-tinged disinhibition of the speaker vis-à-vis her “pretty big little cute guy” (85) is all the starker in light of the previous (penultimate) poem’s pseudoclinical remarks about a cat’s (the same cat’s?) “pleasure in torturing those who are smaller than he” (67). Melgard, too, takes this pleasure. Perhaps all moms do. I certainly recognized my own appetitive, worshipful, quasi-violent, erotic relation to my cat in “Catcall.”

“Lesser Person,” the first cat poem, discourses uncannily, wittily, at length, in traumatology jargon about the speaker’s “son” — a foster — whose childhood experiences of abuse and abandonment the speaker links directly to her own. (He was found “in a field, limping on a broken leg, half-starved and severely dehydrated” [67], whereas she was picked on in school “for being poor […] They threw rocks at me because I was out of step with the others. They could see I was abused. It was written all over me” [69].) The cat’s “ritual” kneading of a pillow, for example, is analyzed in terms of his search “for a nipple that he has lost — one that is not there and will never return.” Writes the mother: “He has no shame about doing it in front of me or an open window for any onlooker to see. He has no need to hide it because he doesn’t realize when he is doing it. For survivors of trauma, reliving the event is an extension of simply living” (75). Son and mother, nonhuman and human, nonlinguistic entity and poet, blur in and out of one another across a field of philosophy (Melgard uses her cat to discuss everything from Aimé Césaire to Echo and Narcissus). Interspersed in the deadpan narrator’s observations of the cat’s behaviors (OCD rituals and “suicide attempts” [78]) is an awful lot of what seems like projection: “He is so broken down, so helpless and vulnerable, that his personal sense of safety requires hypervigilance and constant maintenance to an obsessive degree at all times” (76).

The fetal position, in short, is simultaneously where a parent often finds herself and where she needs her baby to be. Much like Poems for Baby, I am forced, then, to conclude that Fetal Position flashes the reader the same shapes, over and over, in randomized patterns and color variations — so persistently that we end up disoriented, voluntarily seeking out third-degree burns at the hands of the electricity coursing through her stanzas. But perhaps this need not maim us further. Plausibly, if we want it to, this disintegration and reintegration of meaning mighthelp us uncurl. “Yes hurt people hurt people, but repetition also facilitates the passage of the new.” “Repetitions initiate ritual events, wherein the bounds of hierarchies suspend, even invert and the world itself becomes the artist’s pliable material.” “Repetition differentiates. It is a primary violence” (79). Ow.

1. Holly Melgard, Colors for Baby (self-pub., Troll Thread, 2011), n.p.

2. Holly Melgard, Foods for Baby (self-pub., Troll Thread, 2011), n.p.

3. Holly Melgard, Shapes for Baby (self-pub., Troll Thread, 2011), n.p.

4. Melgard, Colors for Baby, n.p.

5. Melgard, Foods for Baby, n.p.

6. Melgard, Shapes for Baby, n.p.

7. Holly Melgard, Fetal Position (New York: Roof Books, 2021), 11.