Stuart Ross exists. Details follow.

An interview with Stuart Ross

Note: It has been many years since he stood on Yonge Street in Toronto wearing a “Writer Going to Hell: Buy My Books” sign (he sold 7,000 of his books this way in the ’80s), but Stuart Ross (b. 1959) continues to be an active and influential presence in the Canadian small press.

Through his work as a poet, fiction writer, essayist, performer, editor, organizer, and publisher, Ross has been an advocate for small press writers and publishers since his late teens. Ross is a prolific writer. Several of Ross’s own books and chapbooks, including Dead Cars in Managua (poetry, 2008), Buying Cigarettes for the Dog (short stories, 2009), Snowball, Dragonfly, Jew (novel, 2012), and You Exist. Details Follow. (poetry, 2013), have received or been shortlisted for awards. His most recent book is Our Days in Vaudeville, a compendium of collaborative poems written by Ross and twenty-nine other writers. Ross lives in Cobourg, Ontario, a small town on the shore of Lake Ontario, east of Toronto.

In July 2014, we discussed surrealism, collaboration as a significant part of his practice, the relationship of his poetics to both Canadian and American traditions, popular culture, mentors, teaching, humor, the small press, improvisation, “nutso” imagery, and his current projects. — Gary Barwin

Gary Barwin: Let’s begin by addressing the surrealist elephant in the room. We’ll leave the sewing machine and the umbrella for another time. Discussions of your work often invoke notions of surrealism, and in fact you edited an important anthology of Canadian poetry that engages with surrealism: Surreal Estate: 13 Canadian Poets Under the Influence (Mercury Press).How do you see your work in relation to “realism,” language, the “real” world, and surrealism?

Stuart Ross: I don’t much concern myself with issues of what is real and what is surreal. I don’t set out to write surrealism, or to include surreal elements in my work. When I write, I simply don’t bother obeying laws of reality, and I have no problem if one of my characters, or some object, transforms into something else or flies, or sizzles, or otherwise does the “impossible.” My reading covers a real range: Patricia Highsmith is one of my favorite writers because I like the closet of terror and paranoia she thrusts me into, and she’s as real as it gets, but I also love Roland Topor’s Joko’s Anniversary and B. S. Johnson’s Christie Malry’s Own Double Entry and Roberto Bolaño’s Monsieur Pain. They’re real too, but they’re not real by being realistic. The “real” world: I don’t think there’s any such thing — or there’s nothing that’s not part of the real world. Language: it’s the thing I write in.

Barwin: But to follow up on your relation to the “real world”: I wonder about how you consider the relation of language to the construction of self, to the experience of being human (or the experience of flying and sizzling)? Much of your language, that “thing [you] write in,” plays with what seemingly bears some relation to a situation outside the language (if such a thing can exist). Your poems often play with the notion that language is a trickster that may appear to construct something that corresponds to the world, but also constructs a parallel world that, based on the experience and expectations of reading, may delight, deceive, beguile, or surprise.

The event takes place.

Sounds are heard.

You exist. Not yet.

(“The Event,” in You Exist. Details Follow.)

How do you imagine the process of reading, of moving through, a text of yours? How do you think about how a reader experiences your unfolding textworld?

Ross: I think more in terms of the discovery of self than the construction of self. That said, I don’t see my writing as a way to discover myself, but instead as a way to explore my interests, to amuse myself, to connect in some way to people outside of myself (however few those people will be), and hopefully provide some amusement for them, or get them to think in ways they find interesting. I’m not sure I understand what you’re saying regarding language as a trickster, but when I’m writing I do like that you can immediately contradict yourself, or skew expectations, or provide another perspective on reality (as in “You exist. Not yet.”).

I like the question about how the reader might experience my work; it’s something I don’t think much about. I mean, how would I know how an individual reader would read my poems or stories? I don’t know their lives, their experiences, what they’re bringing to the act of reading. But I hope that they might look at my poems, especially, the way they’d look at a painting by Bosch. That they’d keep noticing new and weird things. That it might make them laugh at times and unsettle them at other times. I imagine they read the first word, and then the second, and then they keep going, and every so often something strikes them, and maybe they back up a bit or skip down to the bottom of the page. They might attempt to inflict meaning where I don’t intend any, because some people are oriented that way. That’s great! I love reading student papers on my work, and I love reading really in-depth explorations of my writing by creative and thoughtful thinkers like Alex Porco and Lance La Rocque, rare as such explorations are in my case. Throw whatever you got at me! It’s just nice to know someone is considering your work in whatever way.

Barwin: Can you speak about the energy of certain words? Sizzle. Poodle. Potato. (I think you might be the poet laureate of the word thing.) And what about tonal shifts, juxtaposition, and personification?

When we met, the sky had taken a cigarette break, and the clouds, caught

off-guard, were flailing, panicked.

(“When We Met,” in You Exist. Details Follow.)

The ground had a hunch.

Furniture made no sense.

(“You Exist. Details Follow.” in You Exist. Details Follow.)

Honestly, citizen,

have you heard of time?

It’s a thing that matters,

like that other thing,

but less …

(“You Exist. Details Follow,” in You Exist. Details Follow.)

Ross: The word thing is something I love, and I try not to overuse it. On a side note, when I was working with David W. McFadden on his volume of selected poems a few years back, he made a lot of revisions to early poems. He often got rid of the word love and sometimes replaced it with the word thing. But while my interest is mostly in image-based poetry, and I use abstractions sparingly, there’s something big and beautiful about thing — as if you’re talking about something very specific but you actually don’t know what you’re talking about. We’re often bewildered by what is confronting us, and we wonder if what we are seeing is what we think we are seeing. Thing fits that situation nicely.

As for words with energy, like sizzle, potato, and poodle, or moon, canoe, and baboon, or gizmo, spelunk, and Parker Posey, they’re a lot of fun, but again, you’ve got to watch for oversaturation. You don’t want to show off. Poems aren’t about your own cleverness. But these effective, unusual, quirky-sounding words are crucial to my own poetry. They’re like characters in my poems.

Tonal shifts: it’d be boring if the tone of a poem didn’t change. Juxtaposition: again, used sparingly, it can be the heart of a poem, the poem’s energy. Personification: doors are people too, and hammers and broken clocks. One of my favorite novels when I was a teenager was Russell Hoban’s Kleinzeit. It was filled with pieces of furniture and sheets of paper that spoke. I think it’s Hoban’s masterpiece. I see no reason to limit inanimate objects. That said, I’m also interested in stories where the main characters are inanimate objects that don’t think or speak or have any personified qualities. I’ve written two of those, and I’m working on another.

Barwin: Robert Bly writes about poems “leaping” from the conscious to the unconscious. In your work, I imagine not only a leap around the brain but also a leap around the culture. Your poems, in their incorporation of “non(traditionally)poetic” words and tones, popular culture (Parker Posey), and the forgotten material of the contemporary world (e.g., an elastic band, the inside of a shoe, a half-eaten hamburger), as well as larger themes of loss, family history, and more general existential themes, also do a lot of leaping — or perhaps, in some cases, it could be considered “synthesizing.” Also, much of your work uses a deliberately simple tone and sentence structure, often self-consciously so, which is played against more profound issues.

Hi there, inventory of my life.

(“Inventory Sonnet,” in You Exist. Details Follow.)

How do you see the role of this juxtaposition or integration of registers, this creation of a characteristic multilevel style of tonal and image? And maybe this would be a good time to also ask about the role of humor in your work. I like what Victor Coleman said about that: “the message in the chuckle is a punch in the gut.”

… a better poet than me

would insert a really good sediment

metaphor right here. (Or, more poignantly,

here.)

(“Sediment,” in I Cut My Finger)

Ross: The simple tone, as you call it, is the tone I feel most comfortable with. My high-school English teacher once wrote on one of my stories something like “Why are all your characters such blockheads?” Or “so dense”? I can’t quite recall. It felt like an attack, because I identify with these characters. We people, we think we’re so smart, but we’re really not all that smart. So I like those who embrace simplicity. It’s a state that many of us yearn for. Simplicity is a good place to start from to learn profound things. I don’t understand your question, but I hope I have answered it here. I also don’t follow how Parker Posey and the “simple tone” lead to the issue of humor — ask away!

Barwin: Why humor? Sometimes the surprise or incongruous appearance of minor pop-culture figures is humorous. Parker Posey. Montgomery Clift. David Carradine. Or the way the character speaks — often “simple” or earnestly, using non-standard English syntax — is funny in itself while at the same time evoking pathos, empathy or self-recognition. I see these “simple” characters as Beckettian figures. One feels great empathy for their existential or emotional situation and great solidarity with their struggles to express themselves. And one feels a kind of dramatic irony in knowing that they haven’t quite been able to find the right words, but yet, paradoxically, their inability and the language that results is somehow much more telling.

Did I be happy correctly? Do the smile go on my face right? … Am

people in general liking me?

(from “Happy” in Hey, Crumbling Balcony!)

One also feels somewhat the way one feels with Chauncey Gardiner in Jerzy Kosinski’s Being There. The simple language, or the naive yet inventive way of expressing things (“The year is invented.” “The water is solid.”), carries the weight of profound insight, a kind of Zen-like wisdom and presence. This, to me, is also humorous or, at least, piquant and droll.

My father and I build a tent

by the water. The water is solid.

We wait. The year is invented.

He teaches me what it can do.

(“The Tent,” in You Exist. Details Follow.)

Do you see this existential humor in some of your work and in the speakers you create, often a kind of everyperson Busterkeatoning through the language?

Ross: Montgomery Clift is a major pop culture figure! Or a major artist, depending on how you look at it.

But to your question, I don’t see this stuff as humorous, though I know a lot of people do. I’ve become used to people laughing during my readings when I’m reading something I see as poignant. I don’t hold it against them. I’m glad they’re responding. I see beauty in the simplicity of these characters and the kind of language you’ve pinpointed. I feel relief using such language, because it liberates me from having to sound “poetic” like A. F. Moritz or Ken Babstock; for me, this kind of language is more my experience of life, so I embrace it. Again, it comes from a yearning for naïveté, innocence, childhood. Just about everyone in my family has died, so of course I yearn for my childhood. Maybe most people do, unless they had horrible, unspeakable childhoods.

I love your comparison to Chauncey Gardiner. Being There was huge for me when I was a teenager; I’ve never thought of it as an influence, but it must have been. It’s interesting that no other Kosinski character has that “innocence” that Chance had. His other characters are burdened with “knowing” and “intellect” and “conscience.” And then it all implodes in The Hermit of 69th Street, a widely hated book that Kosinski continued to revise even after publication, until he killed himself. That’s his most fascinating work after Being There, The Painted Bird, Steps, and The Devil Tree. The poet David UU had a copy on his “current reading” shelf when he took his own life in 1994.

As for Buster Keaton, he’s also someone whose work I have loved for many years. One of my favorite films of his is Alan Schneider’s Film, from the script by Samuel Beckett. But now when I think of Keaton, I see he had a similar “innocence” in so many of his works. And part of this innocence is self-doubt and self-consciousness. Who of us hasn’t thought, “Am people in general liking me?”

And I think of most of my “characters” or narrators as being everypersons. Everypersons facing existential crises or decisions they are unequipped to handle. Perhaps this is why these characters become fixated on the “thingness” of things. A frozen lake is solid water. A year is something whose invention you must await. Then someone has to teach you what you can do within this thing you’ve maybe never heard of before — this year.

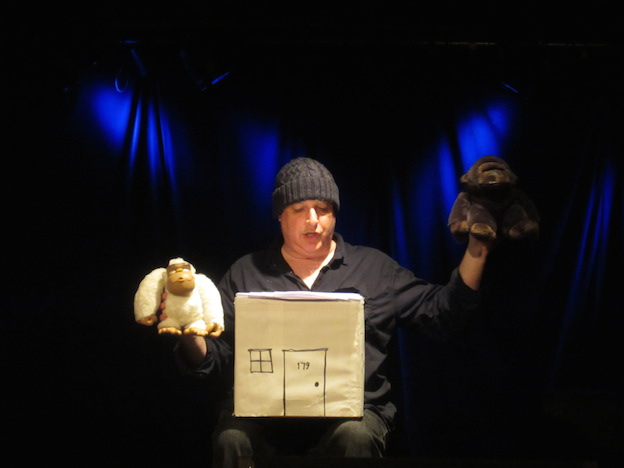

Stuart Ross performing as part of Donkey Lopez (photograph by Laurie Siblock).

Barwin: On the back of your book of reflections about writing and culture, Confessions of a Small Press Racketeer (Anvil Press, 2005), the reviewer George Murray is quoted as saying: “If Stuart Ross was living and working in the United States, and writing the exact same poetry he does now, he would be rich and famous. Well, famous, at least.”

If you do ever become rich, I’m expecting you to buy me a beer … made of solid gold … but do you agree with him about the difference between the US and Canada in terms of poetry, its reception, and the consideration of different styles? How do you conceive of being a writer in Canada?

Ross: George wrote that in his 2003 Globe & Mail review of Hey, Crumbling Balcony! Poems New & Selected. I’ve gotten a lot of mileage out of that line! I’m not sure if I would have been rich and famous if I’d been writing in the US back then, but there would have been a lot more sympathy for my writing. There’s been a shift over the past decade or so away from such strictly nationalistic reading, where poets here barely read the Americans. I’d been reading the Americans since I was a little kid, and as I got older, I was especially blown away by Ron Padgett, Campbell McGrath, James Tate, Bill Knott, Larry Fagin, and a lot more. I loved how crazy these poets’ works were: it was different from what was happening in Canada. Now there’s more cross-border reading — at least in a southerly direction, especially with a new generation of American poets who have some audience here: Lisa Jarnot, Matthew Zapruder, Dara Wier, Mary Ruefle, and others. There’s been a good influence on Canadian poetry. Though I do see the formalist movement increasing here, too. Time for a mud-wrestling match.

As to how I conceive of being a writer in Canada — it’s not something I think about much. I try to write, and find poetry I like to read (which is a very small fraction of the available pages), find a way of paying my bills. We’re lucky here in some ways — because of the existence of various municipal, provincial, and federal arts-granting bodies — but I think the academy has too much clout here. It seems to me in the US you can be taken more seriously for writing more nutso stuff. Or is the grass just greener there?

Barwin: The range of your writing — through your many, many books — has expanded from an interest in (to use your term) “nutso” imagery, structured within a “nutso” narrative to include some other modalities: explorations of more abstract structures (many of your more recent poems include more parataxis, some based on list structures) and some engaged more generally with an increasingly abstract consideration of language. However, at the same time, you have poems that more directly refer to human experiences (for example, grief or loss). Are you now a “deep nutso” or an “avant-nutso” poet? How do you think about the development of your work, from that sixteen-year-old suburban Toronto poet who published The Thing in Exile way back in 1976 to the mature small-town Cobourg poet?

Ross: On my way to look up “modalities” and “parataxis” in the dictionary, I decided to hail some parataxis and let them fight it out over who gets my fare. And I don’t know what you mean by an “increasingly abstract consideration of language.” You have a PhD. I’m just a word schlepper.

Also, do you think I’m a small-town Cobourg poet? I think of myself as a poet who happens to live in a small town. Just as I used to be a teenage poet who lived in suburban Toronto. I don’t believe my poetry was suburban then, or small-town now. A lot of my interests are the same along the whole trajectory from 1976 to 2014. It all comes out of my panic about figuring out how to live in this world, how to arrange events and images so I’m more comfortable. Questioning things — such as the very idea of “good poetry” — because I’m not drawn to formalist verse and I can’t put things in order like the writers of formalist verse do. Given this context, I would say all my poetry refers directly to human experiences, centos and list poems included. It is all emotionally autobiographical, and some more factually autobiographical. Just about every poem is a kind of self-portrait. We choose words and phrases and images and juxtapositions, and all of this says a bit about who we are.

Grief, however, has become increasingly present in my poetry. After the death of my mother in 1995, my brother Owen in 2000, and my father in 2001, the idea of facing the world parentless and practically familyless, of losing friends to death, like John Lavery, Robin Wood, Barbara Caruso, Crad Kilodney, Richard Truhlar, to name a few, and losing other friends to … well, I’m not entirely sure in some cases; the deeper understanding of just how absurd our existence on this wobbly sphere is. It all manufactures grief. But I’ve been strongly influenced by Nelson Ball and by David W. McFadden, and I do try to find joy, too, wherever I can.

As to “nutso,” it’s just nutso. Back in my twenties, I used the phrase “demento primitivo” to describe my poetry. Sometimes I use the word stupid to describe some of my poetry, sometimes goofy. But I still take it seriously.

While your back was turned just now, I looked up modalities and parataxis. They’re good words, and yes, parataxically speaking, I have moved in many of my poems in recent years toward shorter, simpler sentences. In fact, I’ve been writing poems over the past year or so that contain two full sentences in each line. It creates interesting effects and tensions. It contradicts the idea of the line as a breath. It creates two gasps instead.

Barwin: I don’t see you as a “suburban” or a “small-town” poet, but I do see how place and the culture of place appear in some of your writing. The zeitgeist and the spirit of place affect the work, if only because as “self-portraits” the poems often enact the process of thinking, and your context affects you, not to mention providing specific imagery. (I think of the work of David W. McFadden and Ron Padgett in this regard, too.) Does that make sense to you?

Ross: It makes a certain sense to me. But place is just one element, if you’re talking about one’s context. If I am a small-town poet, I am also a Jewish poet, a prematurely white-haired poet, a socialist poet, a youngest-child-of-three poet, a chess-playing poet, an orphaned poet, a nonacademic poet, a poet born in the last scrap of the 1950s on John Glenn’s and Nelson Mandela’s birthday, a poet who dislikes most poetry, and a poet doomed to obscurity. I wouldn’t want any one of these things alone to define me.

Barwin: I want to ask you about collaboration, which has been a significant part of your work. I think these collaborations relate to this idea of poems enacting the process of thinking, or, at least, enacting the process of creation and/or the occasion when they were written.

You’ve written collaborative novels (indeed, we wrote one together, The Mud Game, almost twenty years ago), as well as many collaborative poems. In fact, your latest book, Our Days in Vaudeville, is a collection of poems each written by you and one of twenty-nine different collaborators. What is your experience of collaboration (I mean, other than the fact that collaborating with me was the best experience of your life)? What is it like working with different writers? What does the process bring to the writing of both the collaborative work and to your own solo works? How is a book written with twenty-nine collaborators different? Does it affect how one reads it?

Ross: I’m glad to talk about collaboration, because I believe in it deeply, and I’ve collaborated in many different ways throughout my sorry career as an artist. My first collaborations were with Mark Laba, my oldest friend. We wrote stories together and worked on sound poetry together for about a decade and did a collaborative serialized novel called The Pig Sleeps (it was published in the early 1990s, but we’re currently revising it for an e-book reissue). I was intrigued early on by collaborative works: in my late teens I came across the novels Antlers in the Treetops by Ron Padgett and Tom Veitch, A Nest of Ninnies by John Ashbery and James Schuyler, and Lucky Daryl by Bill Knott and James Tate. (Knott was furious with me a year or two ago for mentioning that book, but I really love it). Later on I gravitated toward poetry collaborations by jwcurry and Mark Laba, and by Brian Dedora and bpNichol, among others.

Of course, I collaborated with you on several poems, a clutch of sound poems, and a short novel. And I’ve worked with a lot of musicians collaboratively — beginning in the early 1990s when a band called the Angry Shoppers lost their singer and guitarist and brought me in as a replacement, adapting my poems to their tunes and vice versa. (You can find clips of that ensemble here.) I have become increasingly fascinated by collaboration. Around 2008, I published, through my Proper Tales Press imprint, a book of Ron Padgett collaborating with Allen Ginsberg, Larry Fagin, Alice Notley, Ted Berrigan, and others: If I Were You. And then a few years later I decided to start compiling a book of my own modeled after that. I collaborated with a few dozen poets and eventually published a book with collaborations with twenty-nine of them, Our Days in Vaudeville. I was hoping it would be the first of many such volumes, but so far the book has been met with almost unanimous silence. Strange, because my books are generally widely reviewed.

On a basic level, I’m excited about collaboration because it allows me to take part in texts I could never create on my own. I can work with writers who fascinate me, often writers whose work is very different from mine. I like that each collaboration begins with negotiation, whether it’s just the idea of taking turns and deciding who goes first, or actually coming up with a form or a constraint to work within. I like the idea of the collaborators, after this initial negotiation, not discussing the collaboration while it’s in progress, because it enforces a more equitable creation of the work — you don’t get to influence what’s happening in the piece beyond your actual writing of the text.

As to what collaboration brings to my solo work, I have no idea. At least, I’m not conscious of it. But collaborating gives me new experiences and exposure to different ways of writing, and I’m sure it ultimately influences my solo work in some way.

There haven’t been many books of collaborative poetry, and those that are out there are rarely taken seriously. Look how little collaborative work appears in literary journals. I’m not sure how people read these books and how it is different from how they read books by single authors. I know that, for me, I became giddy reading Knott/Tate and Padgett/Veitch, for example, because suddenly anything was possible, even beyond the anything-is-possibleness of those individual writers. Some people talk about collaborative writing as being about “play,” but I think all writing is at least partly about “play.” Some see collaborative poems as carnival freaks, and I’m certainly not disputing that with the title and cover of my new book, but carnival freaks are worth taking seriously.

Barwin: You’ve been active since the late ’70s in the micro and small press world. You’ve been called an “activist,” a “guerrilla,” and a “racketeer” (e.g., Confessions of a Small Press Racketeer). You’ve sold your books on the streets of Toronto, organized (with Nicholas Power) the influential Meet the Presses book fair (which became, for a time, the Toronto Small Press Book Fair and has now become Meet the Presses Indie Literary Market). Through your Proper Tales Press, you’ve published a great diversity of writing — in chapbooks, books, leaflets, and other ephemera — of new writers (e.g., Nicholas Papaxanthos, Sarah Burgoyne), legendary figures (e.g., Bill Knott), mid-career writers (e.g., Alice Burdick), as well as your own work. You’ve also edited small press literary journals (e.g., Dwarf Puppets on Parade), created Mondo Hunkamooga, a journal about small press, and have run online poetry periodicals. In addition, you have your own imprint (“a stuart ross book”) at Mansfield Press, a small press out of Toronto, and you’ve been a literary editor for This Magazine.

So, a simple question: What has been the role of the small press (and by this, I include micropress) in your writing and in the writing world in general?

Ross: Before I get to your “simple question,” I just want to correct one thing. The monthly Meet the Presses event over 1985 didn’t “become” the Toronto Small Press Book Fair (in 1987). The MtP evenings at a local community center featured six to ten small-press publishers selling their wares, plus readings, talks, films. The Toronto Small Press Book Fair came about because the huge Toronto Book Fair collapsed, and Nick and I were approached to create something new to fill the gap. So we invented the Toronto Small Press Book Fair, the first of its kind in Canada. I was involved in organizing that event, which was a completely open, non-curated fair, for its first three years. When a rift formed in the Toronto small press community about twenty years later — when the then-organizers of the fair threatened me with a lawsuit after I constructively criticized, on my blog, the job they were doing — about a dozen small-press publishers and writers and former organizers of the fair came together to create an alternative event, under the umbrella of a collective called, again, Meet the Presses (both Nick and I were part of this group). We distinguished ourselves from the deteriorating Small Press Book Fair by making a smaller, strictly curated event called the Indie Literary Market. The idea was to gather the best of the area small presses into one room and create the highest-quality one-day bookstore we could imagine. The first couple of Indie Literary Markets took place while the Toronto Small Press Fair was still gasping its last, disease-ridden breaths. The Market still happens annually, and there are other Meet the Presses events as well.

Now, the role of small press in my writing: publishing, for me, quickly became a practice inseparable from my writing. Writing, publication, performance, and audience happened almost simultaneously as soon as I began publishing, at age nineteen or twenty. Also, I was influenced by the processes and products of other small presses and mags of the era: Crad Kilodney’s Charnel House, Opal Louis Nations’ Strange Faeces, Lesley McAllister’s Identity series, Kenward Elmslie’s Z Press, Dennis Cooper’s Little Caesar Press, and Jack Skelley’s Barney: The Stone-Age Magazine, and of course that insane era of Coach House Press when bpNichol, Victor Coleman, and David Young were there. I later discovered Larry Fagin’s Adventures in Poetry and Poco Loco, Ron Padgett’s White Dove, and many more. And then there were all the other amazing presses that burbled to life, including Beverley Daurio’s The Mercury Press, Daniel Jones’s Streetcar Editions, and on and on.

As to the role of the small press “in the writing world in general,” that’s a pretty huge question and has been dealt with a million times. The main nugget to take away is that small press is the breeding ground of invention. While a ton of bad shit gets published in the small press (as in the big), it’s where the most exciting things can happen, where the most exciting writers find homes. Sometimes these crazily inventive writers pop up in the big presses like Kathy Acker and Donald Barthelme and B. S. Johnson, but most of the activity, the sacrifice, and test-tubing goes on in the very fertile underground.

Barwin: We’ve spoken mostly about your poetry, but you are also a prolific fiction writer, and you’ve done work in sound poetry. Recent books include the short story collection Buying Cigarettes for the Dog (Freehand, 2009) and the novel Snowball, Dragonfly, Jew (ECW, 2011). And the improvisational sound trio you’re part of, Donkey Lopez, has just released a CD entitled Juan Lonely Night. How do you see the relationship between your fiction and your poetry? And how does your sound work — I guess it could be categorized as a kind of “sound poetry” — relate to your other writing? While we’re at it, perhaps you can talk about the place of performance and improvisation in your work, too.

Ross: The primary relationship between my poetry and fiction is that I wrote both of them. And there have been times when I have published the exact same piece as poetry and as fiction, so there is definitely a blur. And when I was having trouble finishing my novel, Larry Fagin suggested to me that I just think of it as a poem; that really helped me barrel through to the end.

I don’t feel my sound work relates much to my other writing, except in that I am its creator. The improvisational work I’m doing with Donkey Lopez (the other members are musicians Steven Lederman and Ray Dillard) is mostly unrelated to my writing, except that I often use elements of my writing in it — I riff off of lines from my poems, and once or twice I’ve used a poem in its entirety — but mainly I see my role in Donkey Lopez as one of three instrumentalists (I play voice).

The sound poetry I did with you and with Mark Laba, and occasionally with jwcurry, was more closely related to writing. But even there it’s blurry: last year in Ottawa John and I did an improvisational piece that was almost devoid of words.

As for improvisation in my work: all of my fiction and poetry is improvisational but exists primarily for the page. I do readings because it’s a good “workshopping” experience, I like doing them, and they help me grow an audience and sell books. I have occasionally done works meant to be performed, such as “The Ape Play,” a puppet show I’ve done a few versions of with ape toys as my actors. The sound poetry, obviously, exists for performance, as does the sound work I’m doing with Donkey Lopez.

Barwin: You are a mentor for many writers. You coach, advise, edit, and teach writing to both adults and kids. At the same time, you are a big supporter and promoter of experienced writers and have enthused about their work and their influence on your own writing. I’m interested in your thoughts about community and the role of the writer as colleague, mentor, and apprentice.

Ross: All those things are optional. They come to some writers more naturally than to others. They aren’t conditions of being a writer. Obviously, I like community. I have organized a ton of readings, workshops, talks, fairs, etc., and for the last six or seven years I have sent out a free weekly email listing of literary events in Toronto (to about 1,200 subscribers currently) called Patchy Squirrel Lit-Serv. But some writers are solitary. They don’t have colleagues.

I apprenticed the poet and anthologist John Robert Colombo for a year or two when I was a teenager. I helped him piece together his anthologies, and he critiqued my poetry in exchange. When I was a teenager I also learned from older writers like Victor Coleman and Sam F. Johnson and David Young and Robert Fones. So perhaps that’s why mentoring comes naturally to me. I began teaching workshops with elementary school students when I was in high school myself.

I am not one of those writers who goes on endlessly about themselves when they talk to other writers (except in interviews like this). Those blowhards are tedious, and they are many. I’m more interested in talking with other writers about their work. I think the deep interest in others is what makes me a good teacher, and what made me a good writer-in-residence at Queen’s University, and what makes me a good editor. But writers don’t have to be collegial, or mentor anyone, or apprentice anyone. I thrive on that stuff, so I do it.

Barwin: I know it’s hard to generalize, but what approach do you take in your workshops and individual mentoring — I mean, other than helping the students create jaw-rending heart-dropping works of impossible brilliance?

Ross: What I want to do in my workshops — and my mentoring — is to expand the possibilities for writers I’m working with: introduce them to new writers and works and ideas and writing strategies, shake them out of their habits and assumptions and complacencies. I want to introduce them to new experiences, help to expand their palettes, dare them to do something in their writing that they are resistant to or uncomfortable with. I like when they write something and say, “Holy shit, did I write that? It doesn’t sound like me. Can I put my name on that?” But I always encourage, and I am always positive. I admit, when I was writer in residence at Queen’s, I told a great young writer, Nick Papaxanthos, that something he’d written was “an insult to poetry.” I figured he could take it. And at the group reading at the end of my session there, he read that poem and introduced it as “Here’s a poem that Stuart called an insult to poetry.”

Barwin: And you eventually published a cool little chapbook of his, Teeth, Untucked (Proper Tales Press, 2011), so I guess both of you saw it as part of a more complex ongoing mentorship based on respect and not platitudes.

Finally, can you speak about your current and future projects? What kind of things are you dreaming up? Where might you imagine your writing going in the future — I mean, assuming there’s not a zombie poodle apocalypse?

Ross: I am currently working on ten different book projects (a story collection, two poetry books, a memoir, a book of essays, a poetry translation, a collaborative book-length poem, three novels). Some of these remain dormant for a few months at a time, or even a few years, but they will all be completed, unless I croak first. I’m trying not to add many more projects, because I’m fifty-five in a few days, and even if I publish one book a year, I’ll be sixty-five by the time I’ve caught up with these. It’s a race against time. And given that I edit about twenty books a year, and do teaching and one-on-one coaching, I don’t have much time for my own writing. Luckily, I’m fast and I think I’m good.

I am entering my literary decline (from not such a great height) reputation-wise, and I have neither the burden of fame nor agents nor audience expectation. There’s a freedom in that. Besides, I don’t want a complacent audience, however tiny that audience. With each book, or each writing project, I try to do something I’ve never done before, to push myself into a new discomfort zone. When I was in my twenties, I dreamed of writing a psychological suspense novel à la Patricia Highsmith. I know now that that will never happen, and that’s freeing, too.