Full-body poetics

An interview with Geof Huth by Gary Barwin

Editorial note: Geof Huth is perhaps best known for his innovations in the field of visual poetry, though he has produced considerable textual and aural work as well as critical and archival endeavours. Recent projects include 365 ltrs, a daily online writing experiment, and his regularly updated blog on visual poetics. Huth’s latest books are Aution Caution (Redfoxpress, 2011), NTST (if p then q, 2010), and Texistence: 300 Pwoermds (with mIEKAL aND, Createspace Independent Publishing Platform, 2008). This interview with Gary Barwin and the poet took place on October 1, 2011, in St. Catharines, Ontario, before Huth’s reading for Grey Borders, and was originally transcribed by Kate Herzlin. — Kenna O’Rourke

Gary Barwin: So the first thing we should talk about is your interest in — [Barwin laughs.]

Geof Huth: In?

Barwin: In mythic creatures. [Laughs.] In taking language, taking poetry off the page, into many different media, whether it’s vocal performance, whether it’s performing art kinds of performances, and movement. So full-body poetics, perhaps you can call it. So, let’s talk about that. Okay go ahead, talk, talk now!

Huth: It comes from a strange place, I think, and it comes from a number of places. But one of them is, and the strange one is, that it comes from the fact that I don’t think I’m a good editor. So I make something and there are lots of my poems that are out there that I think are reasonably good, that I wrote, I sat down and I wrote them, they were done in ten minutes, and that’s all the work that went into them, except to make sure they were neatened up, maybe change the punctuation. Sometimes, or frequently, I just can’t imagine how to change anything I make. Not always though — sometimes change is dramatic. So because of that, because I can’t change anything, the extemporaneous process of creation is the act of making poetry. And so the act of making poetry can also be the physical act of speaking it into the world, or creating it as you speak it into the world.

The way I look at it, everything is extemporaneous, all creation is extemporaneous, it’s based on everything that’s come before, and all of a sudden it gets made. Even editing is an extemporaneous act that takes place after a different extemporaneous act. And so I went into performance because that made sense. I went into doing things at one point in time because it made sense.

But the other reason is, that my interest lies in the physicality of language, so when I edit a poem I usually edit it for meter. So it’s not like I’m saying, geez, that’s the wrong word, or I don’t have the line break right, or something like that. I’m editing it for meter because I think that my ear went off a little bit and I’m trying to get it back. It’s not that my poems aren’t naturally rigidly metrical at all, but they are metrical, and so I think about the physicality of language and being able to perform a poem, even to perform it just by making it up when you’re standing in front of somebody, allows you to live within the language as it truly is, which is that it will be a vocal act that takes place inside an entire body. So the act of speaking and communicating is not just the act of using voice but of using your whole body. It has to do with your face, with where you look, with how you move your body, all of that.

Barwin: It’s poetry as practice, or as process, in the way a jazz improviser, or a traditional musician might construe it in terms of the improvisational element of it. The full-body thing I understand. So do you see it as a representative — the improvisational part — of a process of capturing a certain sort of moment in the life of language or the particular moment of language use as it is filtered through a particular individual?

Huth: Right. A lot of people recently have been saying that what I do has to do with jazz improvisation, and I think so. It’s meant to be a special act, and it’s why when I read poems I almost never read. And if I read a poem that’s written on the page, I usually only read that once ever in public. I don’t perform it another time. I could, because every performance could be a different articulation of the poem, a different manifestation of it. But I don’t because it’s going to be a unique act. When I end, as I usually do, a reading by singing something, usually in an invented language, it’s a completely unique act. Usually the tune hasn’t been used before, the words haven’t been used before, and the people who are there experience something that won’t ever be experienced that way ever again.

Barwin: So are you tailoring what you do, or being aware of that particular moment in the audience, that particular space you’re in — emotional, psychological, as well as physical space? So when you perform, it’s for that particular event in time-space?

Huth: Absolutely. As a matter of fact, when I’m waiting to go on, I’m always thinking about the space and I’m evaluating it and I’m figuring out what I’m going to do, or what I think I’m going to do, because those are two different things when I perform, because that space is going to restrict me in some way and is going to allow me some opportunity in some way. And so I’m thinking through it. Even though it ends up being an extemporaneous act, the outlines of it will be defined. I’ll know some physical things that I’m going to do.

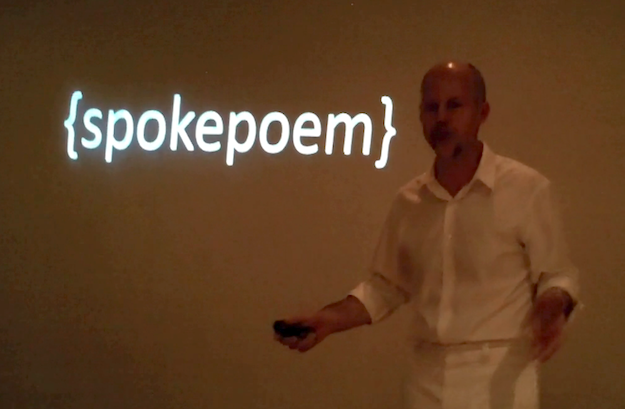

Reading in Chicago, August 26, 2011 (watch Huth's performance here).

So for my recent performance in Chicago, I knew I was going to run across the room and jump onto the window ledge. That was something that I decided I knew I could do because I’ve done that lots of times in my life, and that would meet the needs of the audience.

Before that reading, I was in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and I gave a reading which entailed my taking off almost all my clothes — I left on my underpants. But by being in that space and seeing where certain people were, I noted that in the front row — which was very tight, there was almost no space to work in — there were two people I knew, so I began the performance by taking two things I had with me, one belt that I gave to my friend Mark Lamoureux, and then I took these leaves and papers that I was going to use and I gave them to somebody else, because I could do it with those people, I knew they would accept these objects. And so the space, the people who were there, everything has to come to my consciousness and be used to make the decisions about the performance. Now some of these are very rough decisions, regardless. But even so, I think I sometimes do things that are maybe a little off-putting to people, so it’s not like it’s only choices.

Barwin: That’s what I was going to ask about. How do you account for the dread your audience feels about your performances? [Laughs.] How do you imagine your audience, because there’s surprise, there’s delight, there’s joy, there’s bewilderment, there’s paradigm changes. I mean, when I’ve seen your audiences, there’s a whole range. How do you conceive of their interpretive frame while they’re watching you perform?

Huth: I expect that most people will be a little surprised or shocked, even though I’m not necessarily doing anything shocking. But I was thinking, as we were driving halfway across North America to get here, and that’s just across New York State, that I gave a reading in Minneapolis once, and I ended with this song. Nobody expected it, and everybody was kind of bewildered, even these very avant-garde people that have been my friends for decades. And my friend Siobhan from graduate school came up and said, “Geoffrey, what was that thing you did at the end there? I couldn’t really understand what was going on!”

Barwin: It is called a song!

Huth: I know!

Barwin: It is a behavior that has been exhibited in humans for many tens of thousands of years!

Huth: But in the context of a poetry reading —

Barwin: Right.

Huth: — it made no sense to her, and since it had no recognizable words it made no sense to her. I expect that to happen.

Barwin: This is kind of a code-switching thing. That performance in Chicago … it’s not so strange to jump onto a window ledge, but it perhaps is in the context of a poetry performance. Likewise, reading text from a kid’s writings or reading text derived from the whole wide world of language, right? You’re reading or performing text, making the notations for, the impetus for, performances.

Huth: What are you talking about are these photopoems that I started a while ago, but now I’m pretty intent on them. Because I have a camera on my phone all the time, I can now take pictures of text as I’m going through the world. Sometimes the text is interesting, or I edit out certain bits of the text to make it more interesting so that I have something that I consider a poem. One of them was a photograph of a little child’s poem by a girl who performed the day after I had performed in Cambridge. She read her poem with a lot of verve. And it was very cute, and it showed some real understanding of language, but very simple. I cut that down, and I performed it as a different thing. Or these photopoems are just signs in urban nature that I record and make them mean something. The whole reason for this is to sort of create in the moment, to live in the moment. I create poetry all the time. For instance, I make poetry at work all the time. I go to the restroom, or I’m in my office early in the morning. And I will sing a song, and I will record it, and I’ll either record it on video or audio, and then I will consider that a poem, and sometimes they have words in English and sometimes they don’t. But the act of poetry is almost a constant act. It’s a part of my everyday and every-minute life.

Reading in Cambridge, Massachusetts, July 31, 2011 (watch Huth’s performance here).

Barwin: It seems subversive to be at work and to be creating poetry, and you’d be okay to go for a smoke break, or to call home or something — but to actually create a moment to create a poem seems subversive from the paradigm of what it means to be working, what daily life means, actually. I think it’s really fascinating. You talk about full-body poetics, but I actually see in some of your work this idea of weaving it into regular life. As you’re walking along, you’re recording, you’re performing, you’re documenting in some cases, [and] some of those things become artwork, some of those things just become documentation, and that’s another interesting blur, I think, in your work — what’s documentation and what’s art.

So a further — and perhaps most graphic — manifestation of this, is the 365-day project where you wrote a poem to somebody every single day. Part of that, to me, was pushing physical limitations, as in a Chris Burden performance artpiece. Where it was exhausting, psychologically maybe, in terms of imagination. Because you’re also posting them live online every day, so there was an audience that was sort of waiting for it, ostensibly.

Huth: Ostensibly?

Barwin: Well, I was waiting for it! But that was the notion, that you were subject to outside scrutiny on some level, because you couldn’t just say, “Well, I’m working on this project and I’m redefining it as I’m going.” You’d say, “Part of what I saw in the piece is the struggle with the premise of its own assumptions as a piece.” You’d say, “Well, I’m set up to do this, let’s see if I can do this.” And then there were some online struggles as to whether you were able … as various things in your life happened, or you were just tired.

As you said yourself, it was a very ambitious project, and some of the poems were very, very long. You could’ve written a haiku and just said, I checked that off, I did what I set out to do. But you were actually pushing the physical limitations. Physical and psychological. So I guess I want to ask more about that, about poetry as being part of a life and as being limited by the physical limitations of life.

Huth: “365 ltrs,” which was the project you’re talking about — it did develop over the year as the year continued. But the idea was every day, for 364 days, I sent a letter to another person, and a letter was always in the form of a poem, and it always went back and forth, male and female, male and female. Until the 365th day, in which I wrote a letter to the first person I wrote a letter to, which was Nancy, my wife. And then, since it was only 365 days, her poem had to be fifty pages long in fifty sections because it was her fiftieth birthday on that day. And I began at the day I turned fifty, which was 364 days before that, so there were all these sort of restrictions and sort of symbolic acts built into it besides everything else. And when I originally began it, I thought they were going to be like real letters. If you read them, they’re just like chatty, maybe New York School, poems where, you know, somebody’s just chatting about things, going on fairly languidly. And then the problem was that I had to do something else. I couldn’t just do the same thing. And so very quickly it became that I pretty much had to think of something different to do every day. So every day it had to be in some way different from every day that preceded it. I had to try to write a poem in a different way. I started creating visual poems. I created sound poems that I transcribed. I created all sorts of things, and I sent these out to people who didn’t necessarily expect them, who didn’t necessarily know what to do with them, and who wouldn’t necessarily be able to interpret them. ’Cause one of my issues is, it doesn’t matter if anybody understands a poem. That’s not the issue. The issue is, does the poem exist, and has somebody experienced it, and does it have any effect on them? And the effect doesn’t necessarily have to be positive — that might be a good thing — but it has to be a real effect. It has to be something to remember.

And so this project was my worst project for myself ever to do! It was by far the hardest. Because during the course of those 365 days, I was probably traveling for a hundred of them, and so I was traveling all the time. I traveled all over the place, and I was writing letters at the same time, so it was very tiring. All the time. And it was intended to be. It was intended to be an act of will and physical endurance as well as an act of art. When I get down to it, and I look at these poems — one of which I’m going to read today — I don’t think that they all work. I think I’ll have to edit them, and I’ll have to make them into something, and it comes from this other crazy idea that I have, which is that no poem can be abandoned. Every poem has to be brought back to life. If it’s a dead poem, you have to figure out a way to make it whole again.

To sort of extend what you’re talking about, the other way poetry comes into my life is that I do these little things I call “fidgetglyphs,” which other people would call “doodles.” But my doodles are focused on the representation and understanding of written language, that physical characteristic of language. It’s examining letterforms and visual puns and asemic writing, where they’re essentially things to look at but supposed to resemble writing in some way. I do these all the time: if somebody’s talking to me on the phone at work, I’m writing some of these, and I might do three or four during a conversation. When I’m in a meeting at work, I create these things as I take part in the conversation. They happen in the act of the rest of everything that I do, so that the poetry is inseparable.

Barwin: Inseparable from?

Huth: From myself and from my life. Just as full-body poetics is, the poem is your body, your body is the poem — it’s the only organism that creates the poem is yourself. That’s what it believes and demonstrates.

Barwin: It’s interesting to me — is there a border between life and poetry? So between a doodle and a fidgetglyph: it becomes a fidgetglyph because you say it’s a fidgetglyph. So, all actions undertaken by you, who if you’re considering yourself as a poet or your life as a poem, or life as a locus of poetic activity, becomes poetry. Or not.

Huth: Right. Theoretically, this is a problematic thing. I don’t really define “poetry” or “poem” very distinctly. What I would call it is serious engagement with language in some form. And language has to do with its physical sound, its visual presence, or its intellectual semantics, semiotic meaning. Anything that does that, in my mind, can be a poem. What makes it a poem is its heightened focus on language as opposed to the mere content of the language. Some putative poems that are just narrative really aren’t [poems] because they aren’t doing anything with language; they’re not engaging with language at a high enough level. I’d say that some novels I’d probably consider poems because of how they engage with the language. I can’t really look at Finnegan’s Wake and call it a work of mere prose. I think it’s a work of poetry, for instance.

So I define poetry broadly, and in some ways it’s what is it that a poet makes; this is really interestingly problematic. I was thinking the other day that I’ve had both visual artists and musicians, composers, question why some of the things I do aren’t visual art or music. Why am I saying they’re poems? Why do I sing a song and then say that the entire experience is a poem? That means that it has a melody of sorts, it has a vocal presentation of sorts. I’m not a great singer! It doesn’t have any words. So how in the world is it anything but music?

And the same thing with visual artists; I know this one, Kate Greenstreet, who was a painter originally, now still a painter but also a well known poet. She says, “Why do you call these things poems? This is just art,” by which she means visual art. And I say, “Because this is an examination of language. This is an examination of one part of language, of how it appears to us visually. And how it can have beauty through that visual appearance and meaning. And how it can have meaning even beyond the meaning that is supposed to be imbued within it.” You can have the letter “A,” and it’s supposed to have any number of sounds in English, probably about five sounds the letter “A” can have, that’s really what it should represent. But really, you can draw a letter “A” so that it means lots of different things. That’s how it’s engagement with language.

Barwin: And if you represent something that looks A-ish. It’s playing with how close it is to that.

Huth: Right. Which gets into puns and all sorts of other things.

Barwin: One thing this also points to is the social context of your work. [With] “365 ltrs,” you sent physical copies to people. Sometimes to people who were used to reading poetry, who were used to receiving poetry, and sometimes to people who were not. So changing the kind of audience who would expect that kind of engagement. Even writers aren’t used to getting a poem written to them, sent to them — that’s not typical. In terms of social engagement, one of the ways that your work [goes] out in the world is that you use the Internet a lot. I’m thinking about how you use communities and networks and mail art to open up your work to this kind of process, so it’s a daily thing, or very frequently, so it’s a stream of work. Rather than just a book that’s sort of outside time and space, ostensibly. Or from a very specific time. It’s this ongoing flow of work coming from you, and this sort of locus. I think that’s really interesting: there are communities that are built around this, your main blog as one source of work, but also your other various related blogs, and then the network of other bloggers who respond to you. How do you write in a social and community context?

Huth: Yeah, it’s the unedited life, and maybe a little too unedited. But what it is, is that the process of living is social interaction, to some degree. It’s out there as such in an almost constant stream for two reasons. One is that visual poets, of which I am one, tend to be highly productive in almost maniacal ways. But the other reason is that you live in a body, and until the body stops, you are a living being, and so you’re producing something. You’re producing thoughts. You’re producing dreams. You’re producing sounds. And so it’s replicated through all these different media. And people really haven’t ever before now talked to me about this, but what I think about when I’m posting to my blog — my major blog, which focuses on visual poetry usually, or when I’m posting something to Facebook, or to Tumblr, or Twitter, or something like that, any of these different venues — is that each one of these is just an instance of my being alive, evidence of myself in place. That’s where the mania sort of comes from. But the other thing is it’s just the way to bring poetry into everybody’s lives. I’m trying to both expand the definition of poetry and expand the audience for poetry so that people who don’t necessarily expect it or understand it are receiving something that I consider poetry every day.

On Facebook, lots of people I know are poets, but lots of them are archivists, lots of them are members of my family or just friends I’ve had who don’t read poetry and they’re seeing poetic content whether they want to or not. And maybe they engage with it, maybe they don’t, but it’s an opportunity to do so. It’s questionable whether or not this is really a good process. And lots of people argue, and vociferously, that the worst thing you can do is put out lots of stuff instead of put out only the very best stuff. Maybe I could argue that all I’m putting out is the very best stuff, but I probably won’t, given the numbers!

They think the bad will be washed away by the good, and maybe it will. But the problem is that different people engage with poetry or with any artwork in different ways. And some people are going to be taken by something and not taken by something else, so I provide many different formats of poetry, and even within the formats so many different styles. I think it gives people some ability to find something they like or can be maybe be in love with, even briefly.

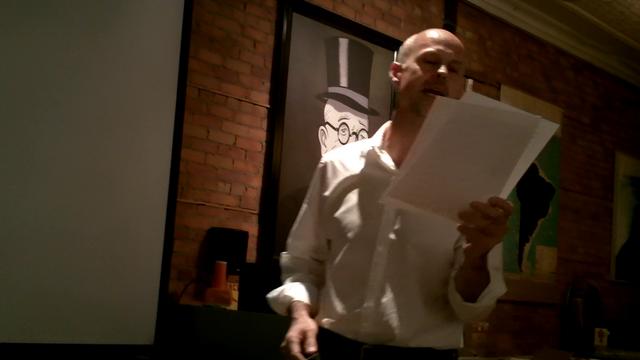

Reading in St. Catharines, October 1, 2011 (watch Huth's performance here).

Barwin: I think I would also relate this back to what we were talking about, about improvisation and flow. It’s not about arriving at the ideal form of a particular work so much as about ongoing process. Ongoing flow, so that that’s where some of the interest of the work is, rather than just saying, okay, I’m just going to wait ’til he comes up with that one really perfect poem!

Not that you don’t have lovely poems, that can be interpreted that way, but it’s about this other element that is really interesting about how it flows through life, how it is a multivalent output of work, it’s reengaging with distribution, with community, with creativity in a way, too, in terms of notions of inspiration or some sort of Platonic ideal of the poem. Your process argues against that. Is that what you’re saying?

Huth: Sure. For instance, one of my poems today is going to be an essay I wrote on my blog. It’s an essay; it’s in paragraphs. That’s the way I wrote it, but I experience it, I understand it as a poem. It’s actually also a review of a book and an unrelated movie at the same time, which people won’t know from today. And it has a sound poem that goes on during it, which gets to the fact that the body is a multisensory organ and a creator of things that can be perceived in many different ways. So I’m trying to get to some gesamtkunstwerk that brings everything into play, so that poetry is what it used to be, which was the sort of height of art. It was that pinnacle of art, but I’m trying to bring it to that by bringing everything into it that I can. I am always failing at this, but always trying to figure out a way to successfully bring smell into a poetic work. It’s not that I haven’t, it’s just that it’s a hard thing to do. We can’t reproduce it well, et cetera. I’m trying to get a way for people to experience essentially living through the poem because it will be touching you in so many different ways.

Barwin: I think smell is supported in Windows 8. No, sorry, that’s the new iTunes.

Huth: There are actually computer people who are working on how to capture, record, and then reproduce smells.

Barwin: See, I just eat while I type, and then I just never clean my keyboard.

Huth: But then there’s the issue of distinguishing between good smells and bad smells.

Barwin: Yes. So something else that interests me is about your work — and I think this relates to this idea of flow and using different media, and also poetry of a life: your professional work is as an archivist, but I also see that impulse to document not really artwork but just many elements of your life on your blog and in other places online, which has a large overlap with your artwork. Not only is it recording activities that you do, or documenting work, or fidgetglyphs that you maybe created during a meeting, but also you sometimes talk about the fidgetglyphs that you’ve documented, right?

You write things like, “Here’s the week of work that I’ve done.” Which isn’t artwork in itself, but it’s discussing it, it’s documenting what you do, it’s kind of archiving what you do. You’ve had things about your own health or your own operations, various things that are all there publicly. It blurs [the line] between what’s art, what’s personal journaling, scrapbook kind of stuff —

Huth: Yes!

Barwin: — and what is deliberately playing with the intersection between these things.

Huth: Right. I’ve always been a poet. I mean, almost always, for a very, very long time. Certainly since my teens, I’ve always been a poet. But I used to not be an archivist in very serious ways. Which means that I used to move all the time; I have moved almost fifty times over the course of my life. And I’m fifty-one, so I’ve moved a lot! When I moved, I would generally say, “Okay, what can I throw away?” and I would throw away tons of stuff. So for this huge first part of my life, I have destroyed virtually everything I wrote. I wrote stories when I was a teenager that were, I thought, hilarious — they probably are still funny now — but at some point I said, “Well that’s not what I want to do,” so I threw them away. I kept tons of diaries and commonplace books when I was a child. Then I threw them all away as I moved on or felt I had grown away from them, so that I was giving up everything. All the writing I did, I said was not good enough, and I dispensed with it. Which is pretty much the opposite of now.

So when I became an archivist — by which point I was a father, so I was a person who was well aware of the temporal frame, and the fact that life is fleeting — I started saying, “Geez, there’s all this stuff I’ve lost.” I still have some things. I have photographs, I have little bits here and there. For some reason, virtually everything I did in Portugal was saved, I think because my parents saved it, and put it in a hope chest. But, I said, “I’ve got to save things.” And so I started saving things, and collecting them, and keeping track of them, so that really the amount of documentation on me is insanely deep, and insanely rich.

Starting sometime in my twenties, I have almost every letter I wrote, I have tons of email, thousands and thousands of photographs, video, audio, all this stuff. So I’m documenting sometimes as an act of poetry, sometimes as an act of just documentation. And all that stuff about my heart surgery a few years ago was really meant to be poetic in a lot of ways. There were a lot of sort of lyrical moments to these little essays about my experience being cut open, and the whole idea about surviving and carrying on with living. It was incredibly important for me to document my wounds. I have this Jesus-like photograph of myself showing my body so you can see all my wounds like Christ on the cross, in forcing my daughter to take the picture when I’m wearing nothing but a pair of underpants — note that I always have a pair of underpants! Because my body was a piece of art. It had been cut open, and there were marks and writings —

Barwin: — notations —

Huth: — and symbols left upon my body. I had to think of them and present them in that way.

Barwin: You’re saying that life itself is written on by poems, or the body is written on by life, and that whole process is a poetic process, right? I was thinking, you know, you can never — as Heraclitus says — you can never step into the same river twice, but you can document every time you step into the river, right? [Huth laughs.] This is how I think of what you do.

Huth: That’s a good line. And again, it’s possible there is too much documentation. One of my projects for the end of the year is to gather together a lot of my electronic media and make sure that I get it to the archives that holds my papers, many of which aren’t on paper. It’s sort of a massive job, because, for instance, over the past year the number of poetic videos that I did is over two hundred. It’s a huge amount of data to manage, and I manage it reasonably well, which is that I note what it is, I keep track of it fairly systematically, et cetera, but still it’s too much.

Barwin: So how do you imagine this documentation? I mean, it’s of interest to people to document what a life is, what a poetic life is, or what your work has been. But how do you imagine what its function is? Having all this material.

Huth: In effect, to some degree, it should document the networks I live within. I live within networks of poets that tend to be a little bit off-center, poets who are visual poets, or sound poets. It documents mail artists. It documents, to some degree, archives. It documents those parts of the world that I interact with and these networks. And these are networks of real people. There are a lot more people than me inside these networks, and it documents them as well as me.

Some of it, though, is just showing my work, it’s the creation of my work, which can then be put beside other people’s work and compared. It allows people to study my work, if anybody ever will — I don’t know if that will ever happen. It allows them to know a lot about my life, so if somebody needs to know about my life they will be able to know about my life, because I don’t close anything. Everything I give to the archives at Albany is open: all my personal letters, all my writings, good or bad, everything. If there’s anything I don’t want them to make open, I don’t give it to them. That’s just the way I deal with them. That’s what archives should do. They’re there to tell us something about the past, because otherwise the only thing you have is human memory and human memory dies with the body. Archives is the preservation of the body and the preservation of the person after death. It’s the only afterlife.

Barwin: Interesting. As you said, the network, too, is really interesting. Often you find out about somebody else by the material that has been recorded, so [it] actually preserves more than one person alive in many cases, not just the person who’s recording it.

Huth: Right, right. As a matter of fact, the stuff of mine that’s at the University of Albany keeps hundreds and hundreds of people alive in all sorts of different ways. I mean, it’s got a huge amount of poetry that would be impossible to find in any other single place. It’s got lots of letters from people, primarily from when people actually wrote letters on paper. It’s got lots of mail art. It really documents these strange kinds of poetry that were going on at the end of the twentieth and beginning of the twenty-first century. We’ll see if it’s interesting sometime in the future — we don’t know now.

Barwin: The last thing I would like to talk about is that you have, more in the past, been involved in theorizing particularly about visual poetry and coming up with terms, trying to develop a vocabulary. Perhaps maybe it’s more theorizing about operational principles, creating a vocabulary so it can be discussed, so that it can be understood better by identifying certain features or taxonomies. So what do you feel that your purpose is, and how do you feel that we can move forward with that?

Huth: Well first I should say I’ve done less of that recently because I’ve spent most of the last year wearing myself out, and I really have not recovered. I used to send mail or postcards out every time I did an overnight. And so far this year I did it once, and it was a few weeks ago, and on almost every card I said something like, life is hard. [Barwin laughs.] And that was about it. That’s taken away from that part of my work a little bit.

But that’s the most important part of my work. That was the important part of the blog. You can’t focus on an individual to get the true value out of anything; you have to focus on something bigger. And so the bigger thing I was focused on was visual poetry. And I think I was successful in trying to bring attention to it, in trying to get people to understand it. Not only in trying to give them a vocabulary, but to give them a way of looking into it.

Barwin: What I didn’t mention is that you often write critical articles or reviews or examinations of other work, right? Using your terms but also giving providing an interpretation, or just a way in for people. Some kind of framework.

Huth: I think it’s important to build an audience for the work, because it is hard for some people to connect with it. But the other thing it’s important for is the artists themselves. Poets go all the time without anybody recognizing that they’ve done anything. They don’t recognize them, they don’t notice that anybody has really understood and really connected with their work. I’m trying to show when I’ve connected with someone’s work. I don’t do it all the time. I forget to do it constantly. I was going to write this great essay, by the way, about this book by this Canadian poet, and I was going to focus on how Gary Barwin is the master of the ending! That the ending of his poems is always a remarkable revelation, and something that I just could never do myself, and that it’s just an incredible skill. I was really going to work at that! But like most of the reviews I was going to do this year, I have yet to do it.

You need to do that, though, because people need to understand that they’re appreciated and that something they do is worthwhile for them to continue. Or at least most people do. Most of the time I say I don’t care, and most of the time I believe I don’t care, because I do things that people don’t like a lot of the time. But even though I’m always worried about the audience, I’m always trying to do something for the audience, like I’m trying not to be boring in the reading. But also, at a reading I do everything I can to essentially — except for to say, “Cut it out” — to keep people from applauding. I leave the room, I sit back down in the audience. I give them no idea whether the performance has ended or not. It’s all to say that I don’t necessarily need that, but I know that certainly most of us really do need that because you need to know that you’ve had some effect. A lot of us will keep going on because we’re crazy, but we’re going to feel a lot better if we know we have some effect.

Barwin: And it’s about interactions. So sending a letter to somebody, sometimes they write back. The fact that it’s an interactional communication in the sense of a message sent and some response coming back. The response doesn’t have to be applause. There’s a connection made, right?

Huth: Right. Absolutely it doesn’t have to be applause.

Barwin: So like a leap between axon and dendrite, if it actually makes that little Evel Knievel leap over that canyon, then the thought has connected, there’s been an effect, a reception. And so feedback is natural. I see that in that sense, it is about audience. You’re trying to give that feedback back to the people who are writing and publishing.

I guess we could end. I am the master of the ending, so I have to end it. We should end the way a criminal prosecution ends. So: Is there anything else you’d like to add to account for yourself? For this despicable act for which you stand accused?

Huth: The thing that I worry about, about all of this, is that the act of creating poetry in the way that I’ve described may be so centered on myself that it may be, in effect, an egomaniacal act in the end. I worry about that. I like to note the things that I worry about because it’s possible to interpret all the time that, Geez, you know, here’s somebody who’s full of himself, blah blah blah blah. Because of the way I’m constantly documenting my entire life, even if it’s only documenting the things around me. It’s not the things around other people, it’s obviously the things around me, because you can’t escape from yourself.

Barwin: I was going to ask: what would be the alternative to documenting?

Huth: You see, that’s the whole thing. You can’t get away from yourself. But there are people who document [who] are really forcibly documenting away from themselves. That means they’re going to places they’re not familiar with, they’re documenting people they don’t really understand. They’re sort of able to strip the self out of there. I really — and this is my only defense — believe that you can’t strip the self away. The self is there.

Barwin: Because all language creation plays through the life. Plays through the body.

Huth: Everybody. Everything does.

Barwin: I think it’s something masterful.

Huth: You’re always trapped in yourself. And then the whole problem, and I said this in some reading I did on a poet’s porch, and it’s the only performance of the reading, that each of us is the center of the world. There are six billion–plus centers of the world on this planet. That’s where everything emanates from, and that’s where everything gets collected into.

Barwin: What I’ve done, masterfully, to decentralize myself, is to run this little blog called dbqp. It’s amazing, because it’s totally not centered on me, and it seems like it does not reflect my concerns or my perspective. Anyway, thanks!

Huth: No problem!