'R's Nova: Where does the [unintelligible] come from?

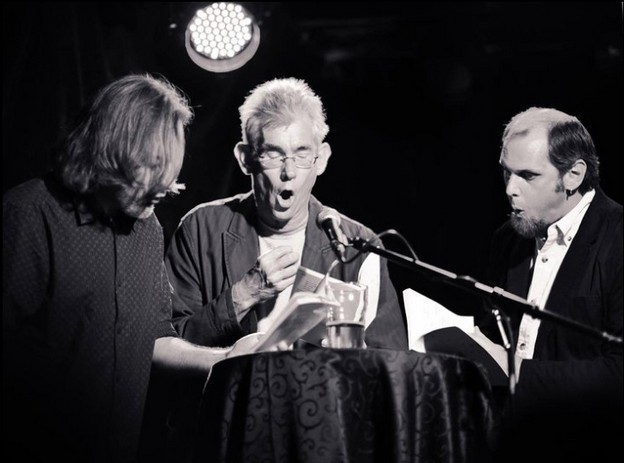

Jaap Blonk in conversation with Gary Barwin and Gregory Betts

Editorial note: This interview is part of a feature curated by a.rawlings, “Sound, Poetry”; it began with a request for material on sound poetry as it is currently being practiced in northern Europe. “Sound, Poetry,” however, accomplishes much more than reportage. Poets from Iceland, Belgium, Finland, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom converse with a broad array of Canadian interlocutors; some have even created new work together specifically for this feature. Here, a.rawlings explains the project:

A term like “sound poetry” may no longer adequately contextualize or clarify what it is intended to represent. It seems a useful moment in the history of this term to reflect on what it means, conjures, describes, encapsulates, and wishes to hold within its reach. It seems personally useful to reflect on the relationship between gender and sound poetry. It feels politically responsible to consider this term in relation to geography.

The wealth of text, audio, and video recordings assembled for this feature is astounding in its range and richness. Accordingly, the five interviews will be published individually in Jacket2 over the coming months. — Sarah Dowling

This interview is transcribed from a video of a discussion which occurred the day after Jaap Blonk performed his adaptation of Antonin Artaud’s seminal 1947 radio artwork “To Have Done with the Judgement of God.” The poster describes the piece: “Banned instantly by French radio this blackened and cathartic masterpiece retains the power to shock and remains an atavistic totem of human barbarity.” Blonk’s adaptation incorporated solo voice and live computer processing. The interview took place amid the visual poetry exhibition Bird Is the Word. Immediately behind Jaap is derek beaulieu’s Prose of the Trans-Canada visual poem.

24 May 2011

Niagara Artists Centre,

St. Catharines, Ontario

Gary Barwin: Jaap, I would say that your work explores on the one hand, the extreme, the grotesque, and a Theatre of Cruelty–influenced performance practice and on the other, an exploration of playfulness and humor, joy, and discovery.

I was thinking about this during Greg’s introduction last night of your Artaud performance when he was recalling when you first met and “jammed” with his one-year-old son Jasper. When Jasper first encountered you, there was a little bit of fear, a hesitation at the unknown, and some discomfort, which soon changed to a pleasure and joy about the exploration, the pure enjoyment of just communicating, of vocality itself. Perhaps this encounter with Jasper is a good way to begin a discussion about the aesthetics behind your work.

Jaap Blonk: Yes.

Barwin: OK, so let’s talk about it! So, it’s two things. One, I think, is that your exploration of language is psychological. And often at the extremes of human experience and energy.

Blonk: Sure.

Barwin: … but it’s also an exploration of human vocal behaviors and possibilities. Sometimes it’s about play, exploration, or about more musical concerns.

Blonk: Yeah, yeah, it can go many directions. There’s also the, maybe we’d call it the antithesis between the systematic way of composing, let’s say a Morse code based on a certain pattern of strict numeracy and a more intuitive means of performance. I learned that I can construct a piece with very dry rules and then in the performances it will come alive, and it will become even better as I respond to it.

Artaud has been very important to me at the outset, when I first began performing voice. Actually, this was in the early eighties — at that time I was just starting with the whole performance thing and I had been in a group of people doing poetry presentations with instruments — people reading poetry by (mostly well-known) poets, accompanied by musical instruments and I was the composer for this initiative. I was not allowed to recite poems — they thought I was not doing it well, at least not in a very convincing way. At some point, the group was planning a performance of Surrealist and Dada poems and there were a few leftover texts which nobody knew what to do with, but they wanted to include in the program. And these included some work by Artaud, and I thought, “Let me try it.” And so, that really felt very good for me to do that and especially the Artaud. This was not sound poetry but translations of some poems of his. We found it very interesting, the whole concept of style, and there’s a famous poetry quote: “Whatever I write I’m going to burn it on the next day, because it’s no longer true.” So these texts were building up an intensity, which helped me go, sort of, across the barrier of madness onstage. So I did that. There was an authenticity to it that I heard — it wasn’t embarrassing to me, it was just intense — so it helped me to go further, to not be afraid on stage, to not be anxious the whole time, to not want to keep total conscious control.

Barwin: Absolutely. So, you go to the limit of that, you explore what’s possible as a performance, on stage, what’s possible in terms of playing a performance through your body and through the resources that you can summon. This is the thing that I’m wondering about: Once you get to the point of crossing the line where everything is open — you’ve gone beyond standard language, beyond standard conventions of vocal performance, you have, as Schoenberg’s song says, “the air of another planet” open to you, and so the question is, then what happens, not only in terms of exploring extreme states but also exploring non-extreme states but with the new resources — new musical resources, new vocal and sound resources that you now can use? Because you’ve knocked down the walls. So, now what? What kind of civilization are you now going to build onstage?

Blonk: Yeah, there’s of course several different approaches to that, one of which is improvisation, which I did a lot, mainly with instrumentalists — different types of instruments — these bring different types of challenge: what kinds of sound to come up with to make sensible music with them. So that’s one thing — just intuition, and so I’ve done completely improvised solo performances, also. So sometimes it’s purely intuitive and automatic, but sometimes there’s a specific thing: I take a structure to use which kind of accumulates, something simple like counting syllables in sound — I use an extended notion of a syllable: syllables of the same sound that’s continuous without a specific break in it, so for instance [see video clip below]. So that brings me to a totally different area and I feel that the materials of the work are very restricted and then based on that I make the piece.

Barwin: It’s restricted but also varied, because the syllable, that notion, is so open to so many things. So many different kinds of performative weight, psychological weight, musical weight are possible, so it’s very flexible.

Blonk: And then, of course there’s also prepared pieces, which can be really hard to learn. There’s a piece of mine — the title is “Barred,” which really consists of — I learned all the symbols of the International Phonetic Alphabet and I used a system that could be written on a typewriter so there were, I think, about seventeen phonetic symbols that could be written using a letter with a bar, or stroke through it, so I used those, for example, in a system of permutations of certain things. So I’d written that, and I’d performed it three days after. It was really trouble — so, terribly hard to do it.

Barwin: A number of your performances of both your own work and other’s work push toward performative extremes so that they become a sort of performative challenge. The audience sees you, the performer, faced with the challenge of trying to realize this extremely difficult piece and so there’s an extra tension that is generated. Not only the excitement and delight of witnessing a virtuoso performer, but watching a virtuoso engage with material that is at the limits of his virtuosity.

Blonk: I’ve never been after virtuosity for virtuosity’s sake. The first time I realized it was when I was working learning Kurt Schwitters’s Ursonate (“Primordial Sonata”), and I’ve always been recording myself, listening to back it, judging my performance. I’d listen to myself and I found myself boring, there are very repetitive passages that go like [see video clip below] and I couldn’t do that one fast enough and I didn’t want to really do it fast to be a virtuoso but to keep them interesting, not boring. So then I made consonant exercises for myself, all different combinations of particular sounds in different orders and I wrote them down and practiced them with a metronome every day but so that the articulation was better

Barwin: Yeah, I can see children begrudgingly practicing from their book of Jaap Blonk sound poetry études in the conservatory, trying to move up to Grade Six in sound poetry, working on their required sound poetry graduation repertoire …

Blonk: Yeah, one time I was renting space where musicians were practicing — I’d have the space for two hours or so — and I’m sitting there with the metronome going. The next student entered with an instrument and was watching me like, “what’s this crazy guy doing?” [Laughter.] Of course, really, it’s the same as practicing scales and that kind of thing.

Barwin: I remember when I first came home from university, from music school, and I was learning how to circular breathe and I was told to practice with a straw and a glass of water, and so I spent all weekend in my parents’ backyard blowing bubbles in a glass of water and my parents were looking wondering what had happened to their child at university — why was he blowing bubbles all weekend? Of course, I assured them that this was an important part of my musical education …

Blonk: I was in this group in Holland where there was this famous reed player and he used to come early at rehearsals and practice high notes on the clarinet and he’d be sitting there practicing very high tones on the clarinet and I’d sit down in the chair beside him and practice uvular trills. He’d ask me, “What are you doing — are you crazy?”

Whereas we both were just working on those things in our vocabulary that we were focused on at that particular time.

Barwin: You’re crazy, yeah. [Laughter.] But just like the instrumentalist, you’ve got a certain repertoire of techniques that you evolve as a writer, as a speaker, and then you work on that with focused practice, just like any art form, any physical activity. You explore what you can do with it and how you can extend it. But perhaps the voice is more obviously both medium and carrier of content.

Gregory Betts: Absolutely. But I think of that guy who comes after you in the music room and his experience on the other side. It’d be fascinating. It’s hard to imagine him being bored by the kind of vocal exercises that you were doing. But I was thinking about last night too, when people were laughing at strange moments, at interesting moments in your performance, even though there was a darkness there. Does it surprise you when and where people laugh? That they laugh at all at things like this?

Blonk: No … no, it’s predictable for me that people laugh. But I never calculate moments that you should laugh, like a comedian. I don’t try and repeat it. But I’ve learned — especially at points in Artaud where there’s no humor at all — it depends on the performance.

Betts: Where does the humor come from? It’s a fascinating moment in a performance.

Blonk: Yes, that’s pretty mysterious.

Barwin: But in a piece there are some more predictable places that make people laugh. When the performer is in a strange position, when something suddenly changes. And sometimes people laugh when there’s an extreme kind of vocalization or an extreme facial expression. And I think people laugh sometimes because the work is so different in that it’s being played through the instrument of the body.

But there are certain of your works that are deliberately playful, deliberately humorous, not that you’re a stand-up comedian, but I’d say that they show that you’re aware of humor, that humor is one of your aesthetic interests.

Blonk: Uh, yeah, well, I think it helps a lot even to bring across other aspects of the work. If there’s humor in one part of the story, it can make another part more bearable.

Barwin: Last night toward the end of the Artaud piece, there was a part where you play two roles: Artaud and a very serious BBC documentary interviewer. “Are you mad?” the interviewer asks Artaud and Artaud responds by saying all this crazy stuff and then continues with some explanatory material. It’s a funny juxtaposition, a funny little scene between this very serious interviewer and Artaud.

Blonk: Yeah. Also, I think it’s important to be able to have access to all the sounds the whole time. It’s more important to me than being able to do virtuoso imitations or copy specific things. It’s important for me to do extreme sounds and then immediately go into a very calm explanatory action [see video clip below] as a demonstration, a transversal unvoiced frictative.

Barwin: Yeah. There’s is that kind of performative play but there’s also, I think, the possibility of opening up the performance to a whole range of vocal and emotional possibilities by imitating of tones as used in society — a dictator or radio announcer, for example — these are all sounds, codes, or “tones” that are available in the vocal repertoire. So it makes sense that these are part of your tools at least as part of these performances, and then you can use them for whatever aesthetic ends that you want.

Blonk: Yes.

Barwin: I’m still really interested how you see the distinction between abstract instrumental sound and vocal sound. For example, there’s musical juxtaposition: you can have a piece that’s, say, a pretty quiet chamber music and then all of a sudden it goes to a death metal, crazy-loud freak out, that’s one kind of thing. But if a performer — a vocalist — goes from a really quiet low-affect expression to a very heightened state, there’s also a psychological aspect, an affective aspect, which adds another level to the performance.

Blonk: Yeah, yeah, I see what you mean … Well, in every performance for me there’s an aspect that’s always there: this joy of making sound. And so, I have this piece, about the Prime Minister where I start to say “the Prime Minister finds such utterances extremely inappropriate” and I start taking out the vowels and it ends up like this [see video clip below] And people always ask me, “How do you manage at every performance to be that angry?” That’s what they think — that I’m angry! But for me, it’s the joy in making the sounds. Of course it’s being conveyed that the Prime Minister is very angry or something like that.

Barwin: I love that piece because it works on all those levels. It works on the political level of the Prime Minister and the use of political language, oppression, and censorship — the removal the letters, so there’s that element. There’s the watching-a-performance element of it where you can see a formal process unfolding. So that’s a completely structural formal interest of watching these dropped vowels and the sounds that result. There’s a level where you end up contorted and spluttering as you attempt to pronounce the results of the process. That’s the level where you see that the body is to sound poetry as the page is to textual poetry. There are all these different levels and elements to that particular piece, which does seem different than some of your pieces which are more abstractly musical. They don’t have the extra-music associations, but are more about delving directly into musical meaning or exploration than the Prime Minister piece where you’re talking about language, involving metalevels and all that.

Blonk: I have a series of phonetic etudes — that’s what I call them — the first explores the r and the different ways of pronouncing it. Of course the r is fascinating — it’s pronounced so differently in different languages [see video clip below] so that was the first. It’s a piece for solo voice.

I think for me it’s useful to think about r. But it’s also so much about poetry so much of our environment has to do with phonetics.

Barwin: Oh absolutely — some of your work explores vocal sounds and some of it explores language. So some words actually mean something, and some don’t mean anything but they’re in the structure of language. For example, much of the CD “Dworr Buun,” recorded by your group Braaxtaal, is in an invented language, so it’s about language, not just sound.

Blonk: I explain in this CD that the texts are written in Onderlands, a parallel language to the Dutch. It sounds like Dutch but even native speakers of that language cannot understand it. People who don’t speak Dutch can enjoy its sounds without worrying about meaning because there is no meaning, so they’re not losing anything. But at the same time, they’re exploring different ways of speech in Dutch. There’s a piece in the speech of very upper-class people at a garden party; the drinking song, which is very much in the dialect of where I was born, and there’s one evoking an experience of a preacher or reverend in a very strict Calvinist church.

I remember one moment where I was a kid sitting in the church and suddenly the power went out and it got dark and the old preacher was, I think, reminding the congregation that the earthly light has gone out but the eternal light keeps shining. He kept speaking for like fifteen minutes after.

Barwin: While you sat in the dark. That’s an amazing image.

Blonk: But of course there’s still a glow of hell. Eternal damnation.

Barwin: As is befitting to remind one such as yourself in need of such helpful moral instruction …

Betts: There’s something interesting, too, in the biographical aspect. It’s not the experience or the actual language itself, it’s not the language or the dialect of the tribe that you’re exploring but the “sounds” of your biographical experience.

Blonk: Some of them are that

Barwin: But in a way it’s the variety of how language is used and people experience of it, whether it’s really militaristic or radio language, pseudo-scientific or childlike or clown-like, or like in the Artaud, sounds of madness or of extreme states. So these seem to be important tools for you, the resources you bring to your work, to examine and explore aspects of knowledge, of experience, and the voice.

Blonk: Yeah, there are those such things which are immediate in existing languages, but for me it was an important step to start using the phonetic alphabet to make sound poems, to be able to mix sounds differently with very much more different colors and different textures.

Barwin: Yes, absolutely, that’s very striking to me as a unilingual person, just to be aware of the richness of possibilities of the r — there are so many r’s you can then bring into pieces and hear the possibilities, and then —

Blonk: — and then go beyond that. Because there are whole categories of sounds that are not represented in the International Phonetic Alphabet — important categories which at least I use to make sound. I think there’s no single language in the whole world where you need to use your hands to speak, because it’s not very practical.

Barwin: I wanted to mention something from your Splinks’s CD Consensus, since we were talking about the r. There is this really great point where you are rolling an r and it’s taken over by a marimba doing a tremolo, and I thought it was a really lovely image of an intersection of musical instruments and voice in a way that I hadn’t thought about: how a rolled r is a tremolo, a vocal tremolo, and its rhythm could be played by a marimba.

Blonk: Yeah and there’s another piece on that CD that’s called “Vowelogy” where I’m using the formants of vowels and they are performed by instruments and so you can really hear different vowels being played by violin and synthesizer and so on.

Barwin: Yeah, the intersection between voice and instrument and how they can inhabit the same soundworld. We talked about your work from the point of view of language art, but I’m interested in how you see yourself as a musician. Where you see the division between poetry, sound poetry, and music — if there’s a boundary? You sometimes perform in a musical context, sometimes in a literary context, and sometimes an entirely different context.

Blonk: Yeah for me it’s really a bit of a useless discussion of whether something is sound poetry or music. I should also say it’s often very complex. I’ve been a member for several years of a symposium that was started in Germany. And actually all of the discussion was about if things were poetry or music.

Barwin: Yeah, absolutely. There’s a large monster coming towards me that’s going to kill me. Let’s discuss how to define what it is rather than just escaping from it.

Blonk: Instead of actually talking about the piece, yeah?

Barwin: Exactly.

Betts: Sometimes these bureaucratic divisions between the genres are used as a way to exclude. Certainly in terms of funding.

Barwin: So, these divisions are not useful then, except, as you say, to bring a richness to the interpretation of how a work relates to a certain tradition. How a work takes a tradition and explores it, takes it in a different direction. You can appreciate what it is for itself, but also at the same time you can appreciate what it might be in its relationship to literature as a way of deepening the experience.

Blonk: Yeah, for me it’s very much all one thing … for instance, the titles I make up for mainly improvised music. The musicians don’t see that when we’re recording. I make up the titles after the fact … Sometimes they’re anagrams … I hope that listeners they will see something there … but most of the listeners are people who have no connection to sound poetry or the tradition of poetry in general and in school.

Barwin: In some of your work with musicians the nature of your engagement with language varies. At one moment you’re performing things that sound as if you’re interacting with text, then you’re interacting with musicians as if your voice were an abstract instrument, and then you return to something that engages with language — is it speech, or is it song, is it text, is it language? There’s an interesting play back and forth between what appears to relate to language and what is more abstract sound.

Blonk: Sometimes I, as it were, step outside what is happening and comment on what’s happening, or I’ll be trying to be a translator and translate what the musicians are doing into another language. Sometime I take that role and see what happens.

Barwin: You also use technology. In one of the sections of the Artaud piece which you performed last night, you used a PlayStation controller to control the computer sounds. And you also used processed vocal sounds. In other work, you perform what sounds like vocal imitations of machines. I’m interested in your approach to the technology, how you think about technology and how it related to the voice, to the body, and to gesture.

Blonk: I was already composing music before I started vocal performance. The aspect of composing, of making, has always been more important for me than being a vocal performer in the sense of performing pieces by other people. But most important to is to create my own material. At some point, I discovered that the potential of the voice was a great source of material. I had the voice but also the potential of the instruments of the people that I was working, but I also like using well, basically, effects and samples of the voice that can extend it even more in the sense of density, register, and several other aspects. So I started using them from a compositional point of view and also in improvising. I learned many of the possibilities from improvising.

At first it was just hardware — effect boxes and after that, software. At first it was just commercially available hardware and software but then I developed things in Max/MSP and things like that. At some point, in 2006, I took a year off of performing, a sabbatical, and I started learning programming languages and seeing what was possible. Really to learn to start from scratch. Also synthesizing sounds.

Betts: The sounds that we were listening to last night, that you were you were playing with a joystick, were those ones that you had composed?

Blonk: There were some long sounds that I did not control with the controller. But they were the result of the manipulation of voice sounds.

Barwin: So then many of the sounds which sound mechanical or synthesized actually have a basis in vocal sounds. And then using a gestural controller also makes a sound somewhat vocal because you’re not flipping switches you’re actually controlling through physical gesture — the movement of the PlayStation controller. Are there sensors which are tracking the movement in three dimensions?

Blonk: There are only two sensors which basically track only two variables. Forward and back and side to side. Of course, I can connect more than one parameter to each movement.

Barwin: That’s another way these computer sounds can enter the vocal realm: through the physicality of gesture. This is in addition to the fact that original sounds themselves are derived from vocal sounds.

Blonk: Yes, it’s important for spectators to have some link with why the sound changes. It’s not very interesting for the people to do like many laptop performances where there is nothing visible happening in the performance and we have no idea where the sounds come from. I always think about that: why should I listen to this in a concert? I’d rather have it on a CD, except for when they use multichannel systems, then it’s different and it can be interesting to go to the concert.

Barwin: So there should be some connection between the performance or the performer and the sound being produced in some way that’s meaningful to the audience. That makes a lot of sense.

And in the Artaud piece performed last night, there was a lot of talk about the body, about bodily functions — talking about shit, about organs, about the body — so it made sense to have organic sounds from the computer that seem to relate to the body. And it provided some really funny juxtapositions. Also, there were sounds that sounded like body sounds which then changed and sounded like something else. That was a really interesting play with sound and association, or sound and source. That was really great.

A question about tradition. I see quite a few people from the sound poetry and avant vocal tradition who do this experimental work but are also advocates and performers of much older work — by Artaud, Hugo Ball, Schwitters, and so on. You often see this work performed in the repertoire of the vocalists. Do you see this work as meaningful to you? As canonic? Are you arguing for it, trying to keep it alive and in the repertoire?

Blonk: Yeah, I think not so such any more, but when I started performing Ursonate, these pieces were very much neglected. It felt for me when I discovered the piece in 1979, it really felt for me like I’d discovered a masterpiece. I wanted to fight for this piece and perform it a lot. I’d do performances in punk clubs where I was opening for a band. And the audience would just want talk and have a beer or listen to the band and not have to listen to this stuff. So they were throwing beer at me — I had many such unpleasant experiences. But I always finished the piece.

Barwin: You’d notice the people throwing the beer at you, but you wouldn’t notice the people who were interested, though.

Blonk: There were people interested, yes.

Barwin: Less obvious, certainly than people throwing beer.

Blonk: Sure. There were probably people cheering, also.

Barwin: I like the idea of choosing a challenging performance situation. That’d be a challenge to perform there. It’s a very different situation but has a lot of commonality in a certain sense with that audience that might have originally heard it. It’s different that those people who walk into a punk club to play the Bach Solo Cello Suites.

Blonk: I’ve performed the Ursonate at the Amsterdam Concertgebouw, at the official series for subscribers. I had to perform in between two traditional sonatas for very middle-aged, typical classical music audience. They were taking out their handkerchiefs so they could laugh into them. [Laughter.]

Barwin: But it’s like I was saying about these performances in relation to traditional music or poetry, recontextualizing something, you learn something about the piece.

You hear a sound piece differently at a punk show than in a traditional concert hall. Each reveals an aspect of the piece in relationship to the tradition that it appears beside. I think it’s a good way to gain another understanding of the piece.

You also work with multimedia. You have videos of performances. Some are recordings of performances which are then modified. Some are abstract videos which are works in themselves.

Blonk: It’s a very recent thing for me. It’s only in the past year that I have been exploring this. I’m still developing them. I have some longer videos that if some opportunity shows up, I would like to show in an installation context. I have had some small exhibitions of my sound poetry scores and visual poetry usually in combination with a performance, so I can imagine at some point, an exhibition with projections of the score and so on.

Barwin: There’s a video posted on your website, Flababble: It’s very simple but really charming and fascinating. It’s a recording in very slow motion of you shaking your head from side to side while making a “cheek squeak” sound. I’m fascinated by how this simple and captivating thing explores what actually happens, a close examination of what happens to the face when you make a sound. And all that is changed is one parameter: time. It’s a really mesmerizing video.

Blonk: I was very surprised myself at seeing what’s really happening when you do that. It only moves this much if you do it really fast. [Shakes head and makes “cheek squeak” sound.] But at normal speed, it’s too fast to see what’s actually happening.

Barwin: It’s like those pictures of the horse by Muybridge, where you see all four feet actually leave the ground. There’s a real poetic beauty about seeing something taken out of its original time context. But going back to what I was saying before, I see a strange beauty in it, but also a playing with the grotesque and the extreme because you can see the face moving so radically, and you think, okay, is this ugly? Is this beautiful? What is this? And you have to consider what you think of what people do, what you think of the body and how we perceive things through the mediation of time.

Blonk: And there’s also, yeah so this is just a video shown in cheap slow motion. [Laughs.]

Barwin: Yeah. But there’s a whole range of Internet work that is deliberately lo-fi. It’s like the aesthetic of badly Xeroxed zines and things that are trying to have that look. There’s a charm to that look. And in a way, this is one idea, one approach. It’d be another kind of piece if it were done with extremely high production values. It’d have a different effect.

Finally, I like to ask you about scores and notation. And also about text-based work with computer generated texts. So I guess: scores and generated text.

Blonk: Yeah, I have several of these generated texts taking very well known poems in Dutch and German and making variations of them with a computer them using Markov chains.

And of course they were transformed into nonsense language, but there were still enough points of reference for people to recognize them. At some point, during a reading, more and more people recognize the source.

Barwin: It’s fascinating, the highly advanced pattern-recognition that we have, especially with regard to language.

Blonk: I’ve also made Markov variations of my own sound poems. I created a series of variations and then I used another series of mathematical procedures to generate more texts.

Barwin: It’s like what you were talking about earlier. How simple mathematical processes result in these rich experiences because they’re using language and using vocality. And a single regular and mechanical procedure becomes variegated and complex when multiple generations of the process are used. And then added to that, when these texts are performed, there’s another whole level of organic, performative richness.

Blonk: Yeah.

Barwin: Jaap, thanks very much for this discussion. It’s been fantastic.

Blonk: Thank you.

Barwin: Now I’m going into the practice room to practice my voiceless velar fricatives. I’ve an exam at the Royal Blonk Conversatory of Mouth Art, later this month …

Edited by a.rawlings