Textile practice and the no-audience imaginary

Last June I sat looking at this “sampler” by Elizabeth Parker in the textile archives of the Victoria and Albert Museum. I put “sampler” in quotes because I do not think this piece really is one and neither do the curators and archivists. What is this object? What might it say toward a textile poetics? Similarly, the stitched works of Arthur Bispo do Rosário are called “outsider art” yet they were exhibited at the 2013 Venice Biennale.

I do not want to comment on the high art/craft divide or museum and art world ethics/politics—though textiles are often in the middle of those debates. And I have written about Parker’s sampler before. But in this commentary, I want to consider the action of making these works and what can be learned from the probability that while these stunning objects were being made, they may have had no imagined audience.

Since my first commentary in this series, I have been entertaining the idea that a textile poetics forefronts the ritual aspect of making—performing the same gesture over and over is a key feature of a textile practice.

In this commentary, I want to say that a textile poetics can encourage us to jump across mediums, to invite collaboration and learning, and in so doing, has the potential to refresh our practices. This may be related to what Kaia Sand terms “inexpert investigation.” (In a future commentary I will write more about Sand’s work—my advanced poetry workshop this semester is themed “walking” and we’re about to engage Sand’s practice that marries research, the public, stitching, books, and politics. Stay tuned.)

For now, let me suggest that “inexpert investigation” is made materially manifest in the Parker sampler and Arthur Bispo do Rosário’s stitched works. Both exhibit the power of the mark that shows its own discovery, its own learning, its comfort with variation, that does not necessarily imagine a set of critical eyes who will situate the artifact in an art or literary critical discourse, or judge it by craft guild standards.

I could call myself a “trained poet and artist”—and because of this, I want to take seriously “sneaking up on myself,” being desirous outside the boundaries of known materials, practices, techniques. Perhaps a textile poetics takes limited materials, technologies, and skills as constraints and shows how we might shed self-consciousness, shed expertise in order to make works of brand new intensities.

Two weeks ago I suggested to my students that when we make a poem or artwork it is released from “the personal,” and after that release we experience its feedback, its teachings; the work’s energy is made possible through distance. “Inexpert investigation” creates this distance quickly: work depersonalized through an abandonment of “expertise,” a step out into new territory. “The word”— often sacred and so special, especially to younger poets who understandably come to poetry with a mix of fear and longing—becomes other-than-ours via art. And for me, stitching words infuses them with so much “otherness” that I think I can finally “see” words as vibrational entities of their own.

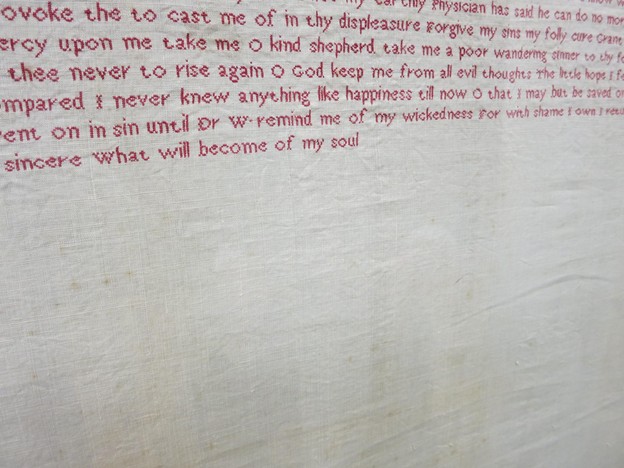

A close read of the Parker text/textile reveals two things: her cross-stitching was impeccable. She performs mastery in this stitched work—so it slips out of “sampler-as-practice-sheet” realm. The second revelation is that this work is a long, repetitive confession and an appeal to God for forgiveness. It is not clear who the audience would have been.

Parker was a domestic worker who found herself in abusive households. She wanted to commit suicide. She was delivered from her situation and so she didn’t—yet the last portion of the sampler is a relentless repetitive request for forgiveness for her wicked self-destructive thoughts. It ends with the phrase “what will become of my soul” and trails off leaving a third of this linen substrate empty. It is a massively beautiful and intense artifact.

The idea that this sampler’s “writing” is cathartic like “free-writing” or “automatic writing” is problematized by the extremely perfect technique. That she should treat such wild, rambling, self-disclosing thoughts with such care is the power of this piece. There are even doublings of words, and as she stitched, she surely would have noticed this as “mistake” and snipped away the “extra” word if she wanted to. That she didn’t tells me that her work is at the borderlands between what Deleuze and Guattari would call smooth and striated space. As I articulate in my last commentary about embroidery as occupying both of these spaces: Parker mixes wild language, disciplined stitch.

The notion that Parker’s was an unimagined audience brings me to the word “display” and Arthur Bispo do Rosário. He made tapestries and cloaks to hang on a wall, to hang across the shoulders.

What choices does a person have if they want to make text large and more overtly “public” if they do not have access to technology, printer’s tools, paints and canvases, paper, wall space to mark? One answer is in the way graffiti writers take wall space.

Another answer is embroidery. It is said that Bispo do Rosário used unraveled thread from hospital gowns to make his embroidered pieces. Fabric, material, thread is all around us. It is very easy to learn how to stitch.

Which brings me to a thought I have had for a while: there may be a relationship between early printing technologies and stitching—the slowness of forming each letter makes stitching akin to the up-close act of setting type. Can a textile poetics can marry these three things: writing, print-making, and stitching? Yes, if we think of stitching as related to the action of setting type, or printing’s possibility to make words large, to “posterize” language.

Embroidery allows for broadcast, extra-book language, worn or hung on a wall. But unlike other arts that require technology, whose techniques and materials require an association with “fine art” or the craft guild, embroidery is both ritualistic in action and accessible in terms of materials and skills. This is fertile ground, I think.

A textile poetics