'In poetry all things seem to touch so they are.'

In what will be my last “a textile poetics” post, I return to some familiar themes or where I started: tactility and weaving and language. This time, I proceed by way of a weaving and writing workshop I lead in Kuwait, an essay by Tyrone Williams on ecopoetics, a brief consideration of Susan Howe’s work, and a mention of a lecture on exile by Costica Bradatan. Also on my thought horizon: a project I am working on called “last book” which is a drawing sequence accompanied by a book of random, highly excerpted entries from twelve years of notebooks. This book will be “published” with no cover art, title, author, other marks of publication, and will be made — printed locally — in an edition of 99. A stack of white books, limited in number, yet unnumbered, and made without a distribution plan.

In “Outsider Ecopoetics: Notes on a Problem,” Tyrone Williams asks, in response to the problem of language and anthropocentricsm: “Is it possible to think otherwise, to imagine a future within a speculative horizon of ‘freedom,’ an ‘outside’ for that which has yet to be, and by definition, cannot be, thought?” Considering ecopoetics, he suggests, “our responsibility to a delimited future may also be an act of irresponsibility to an indeterminate future.” How to be responsible to indeterminacy—to the future? And what does this responsibility look like for poets, a poetics, for word workers, artists?

Toward an answer, Williams writes:

“If I provisionally retain the term ecopoetics for that which has, however tenuous, some relation to the book, another human creation, it is because a poetics per se demands the book or, more precisely, the structure of the book, which is also a structure of desire. For the book is not a tome of plentitude.”

Reading this, I reach, immediately, for Susan Howe’s books. Her “structures of desire,” her project of shaping a lyric from what is lacking—documenting those who find themselves in the stutter, as she has said: the poetics of the outsider poet, philosopher, the “wrong” gender, the eccentric intellectual whose productivities never meet equally productive academic and public receptions. Her re-coveries: beautiful partialities, themselves. From her introductory essay in Pierce-Arrow, where Howe tracks the relationship between the philosopher Charles S. Peirce’s practices and his partnership with his wife, Juliette, who told fortunes and said, about Peirce, “He loved logic”:

“In poetry all things seem to touch so they are.” Mysticism and logic. Language and the conveyance of touch. Home and away. Failure and success. Limits and the nether realms.

With this in mind, I go back to Williams who suggests that thinking about the book as limited lets us remember that the body is also delimited. And I think he may be saying that an experimental poetics also teaches us how to resist or extend the limits of the body. Resistance as productive, future-oriented. He concludes:

“. . . in the end a resistance against the biocentrism of the body as such, against the anthropocentrism of the book as such, might offer glimpses into an ecopoetics no longer at the apogee of its orbit about a center. Imagine, if we can, an ecopoetics untethered from the earth, a body no longer bounded by the concept of a globe or sphere. Imagine a body adrift from embodiment, a book, like love, unblurbed . . . like love, unblurbed . . . like love, unblurbed . . .”

On his way toward this rapturous conclusion, Williams notes, and I think this is important for this commentary on textiles and tactility:

“. . . visceral experiences—touching hearing, smelling, etc.—cannot be communicated to third parties without the midwifery or middleman of language. This means that even if a new subjectivity displaces the old subjectivity of the book, it cannot, today, make it itself known since our language is both the origin and destiny of the book.”

An exciting crack in my initial intention emerges.

When I began these commentaries, I was considering the end of my writing. Not in a negative, “quitting” kind of way—no, not at all. But in an “off in flight,” new media kind of way. For a couple years, as a poet, I had been basking in textiles: desirous of their colors, the tactility of them, their no-language possibilities, the “outsider artist” or craft knowledge available in their study. Sidling up to textiles, I was imagining my “last book.”

In fact, I may have been orchestrating a return. By way of Kuwait, a place I had never imagined I would visit.

Last week I traveled to Kuwait—to Gulf University of Science and Technology—where I had been invited by Alan Clinton and Ikram El Sherif to give a reading and workshop at their second annual foreign language learning conference. After a day of intense travel mishaps, a scolding at immigration, a lost piece of luggage containing all my workshop supplies that eventually did arrive but not until the middle of the night—after arriving in a place intertwined with my young adulthood and a long era of conflict—“The Invasion of Kuwait”—I learned that I may be in a state of always-returning to the book and body’s limits, which means I am also always-leaving toward their futures.

I read my poetry right after philosopher Costica Bradatan gave a lecture on exile and its beauties. He spoke about tango as the shape of the longing of sailors, coming into port and then leaving again. He spoke of Paul Celan. He spoke of the artifice and the beautiful limits of writing in an “other” language. I thought of estrangement and my beginnings in writing: in 1989 I went to Austria on a whim for a year and put English aside and tried on a new identity which returned me, intensely, to English.

I thought of my current situation: coming up on two years in the Middle East, miles from “home,” in a place that had been used, ideologically, to define my nation home—“them” versus “us” and “conflict” versus “safety”—and the intense disruption of September 11 to an aspect of that opposition, an opposition I already knew was false. Then that event was used to deepen the idea of difference, of violence perpetrated only by the other. Finally came economic violence at home: what would eventually spawn my (literal) flight away. What does my self-designed transport to this place bring to my person, my body, my book? If I am aware of never having seen my own home in opposition to the Middle East, how does the difference of this place register in me when I arrive and as I am staying? Is it like appositions drawing nearer and nearer? (Tyrone Williams’ essay touches on appositions versus oppositions.) Feeling like a person for whom “here” and “there” are both echoes, I read poems into this exile echo chamber of a lecture hall—Bradatan’s exile talk ringing around us all.

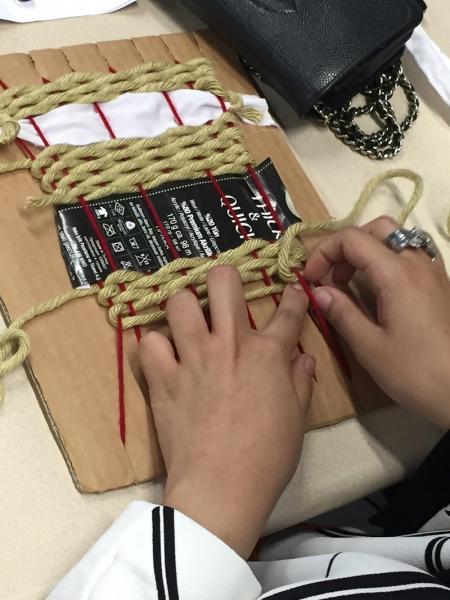

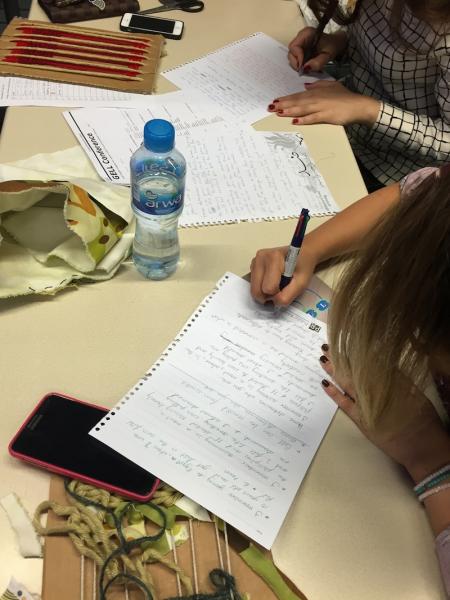

Then, after, I gave a workshop on weaving and writing. In a classroom, away from the lecture hall, things seemed to settle: we made small, page-sized weavings, and as we worked, time opened up and there was delight in the room. We spoke about choosing colors, textures, a double-weft weave, the way that resistance—the fibers going up and over, up and over, alternatively, and pushed down near to each other but not on top—makes cloth, a thing that can be released from the loom.

We segued to writing. The students shared these works and their writings were stellar: filled with sincerity and irony, juxtaposition and unity, longing and contentment, humor and sadness. How did these writings arrive? I thought about this and realized that my writing exercises designed to mimic weaving had very little to do with weaving. There was no overt “textile poetics” being enacted, though this had been my plan. What had mattered was that we engaged in making something in order to begin. Our hands were active. We were touching textures of string, making choices by feel and by desire often unattached to, exceeding the verbal.

Were we exceeding the book? Our bodies? And then, upon return to the page, did we loosen earth’s tethers a bit? I thought of the floor loom—of the Bedouin weaving tradition and the sadu weavings we saw on display in Kuwait. A woman sits on the ground and the loom extends out from her body. Her legs may stretch out on either side. The limits of the loom are clearly demarcated yet in that space she makes something new: a cloth. The loom’s width limits one dimension of the cloth’s future. For a while it is attached to the loom. Then the weaving is cut and tied off. Continuation and limit. Tether and loosen. String and slack. I think of Tyrone Williams’ idea of the sentence that trails off with a preposition, indicating “another space, another temporality” and I think these are the right textile words to leave this commentary space with . . .

A textile poetics