Touching words

Advocating for the downplayed, epistemologically outcast sense of touch in her essay “Textiles, Text and Techne,” collected in Hemmings’ The Textile Reader, Victoria Mitchell writes: “It is clear that textiles are not words and the differences between them benefit the conceptual apparatus of thought at the expense of its sensory equivalent. Thus when an activity is labelled as textiles it ceases to be a substance and becomes instead a ‘material of thought,’ and as such enters into the internal logic of a system which tends to privilege the autonomy of the mind.”

I would like to complexify Mitchell’s claim by extending two of her subjects: words and the senses.

Victoria Mitchell’s essay begins by recounting Charlotte’s Web and that clever spider weaving words into her web in order to warn her friend the pig. Mitchell articulates that of course the story is a fiction, and a spider’s ability to make webs “is understood in terms of the mechanics of the nervous system; it therefore falls short of the kind of language experience typically associated with the written word.” Mitchell explains that “text, textiles and techne are etymoloigcally linked” but claims that language and textile have been separated, and that “the privileging of words and the ocularcentrism of western culture can mask some of the sensibilities conveyed through textile practice, and that making sense through the tactility of textiles has implications for perception in a wider sense.” I agree.

But what happens if I “flip” Mitchell's thinking by beginning with another idea about words: that written words may also be “understood in terms of the mechanics of the nervous system” and that this other idea about words and practices of inscription can successfully get underneath ocularcentrism? What awareness opens up if we begin with langauge experiences that are considered atypical instead of typical? Would this help to rescue touch and textiles?

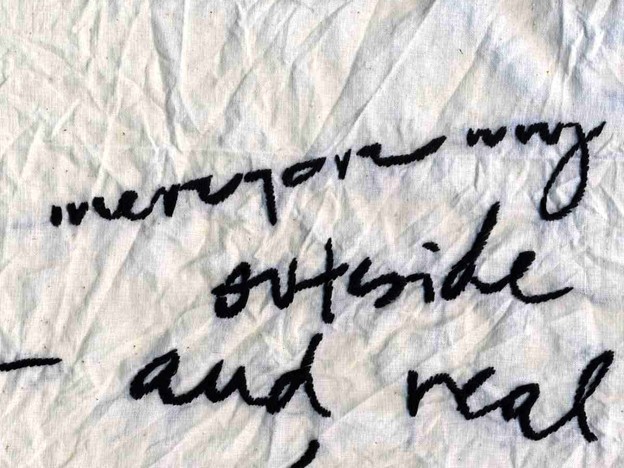

Leslie Scalapino’s poetics can help me execute this flip, I believe. In “Poetic Diaries,” an essay collected in How Phenomena Appear to Unfold, she makes this articulation: “Therefore my thought, and events which are outside me—and really are me—and the world, are the same. Very painful events may seem to have longer reverberations. Which cause their own reordering. This implies a syntax which in being read would require that the reader go through the process of its thought, have that thought again—and it’s therefore an act, one which has not occurred before. A thought of the writer isn’t giong to be duplicated.”

When I first encountered this essay in 2011, its ideas seemed so important yet difficult to me. To try and make sense of this, I wrote her words in my notebook, scanned those notebook pages, and stitched the statement. The image that begins this commentary is from that stitching project.

Scalapino returns text (in case it ever left) to a realm outside of representation, beyond “the autonomy of the mind.” With this poetics, we have the opportunity to insert a wedge into the over-valuation of the written word that might be rampant in certain contexts. Here I am thinking about the poetry workshop in university settings and that perhaps a training in treating the written word as material of touch sits well with what we know, deeply, to be true about writing—that it also resides somewhere beyond thinking and seeing. Re-familiarizing ourselves with this may return us to the business of argument with new attunement.

Last night I heard my colleague Andrew Starner, theater maker and theorist, read from his essay “Words from Another Place” and today I think that his dispatch from the world of performance studies—his notion of language and inscription dovetails with Scalapino and with “another” sense of language. From Starner’s abstract: “Recasting the successful theatrical monologue as a working-through by the actor of the ‘trauma’ of ventriloquism, this article suggests that while the words have indeed come from another place, when the actor has made them her own, she achieves (an) identity in this process. If the short essay that follows were intended as advice to the actor, it would be not to see the monologue as a way to go deeper ‘in’ to character, but instead as an occasion to become a medium for a real broadcast ‘out.’”

The currency assigned to going inward while writing is quite high. But I like this idea of “broadcasting out” in the very act of writing. A textile practice and textile research has helped me understand the way my writing practice is very much about touch: surfaces as prosthetic moving me out further into space, into world. I have begun to regard, with more seriousness, the repeated brushing of the side of my hand against the surface of my notebook. The continual motion across. I am more aware of the connection between sound, touch, and word that I associate with keyboard tapping. The touch of hitting the return key and the texture of whitespace enters the document. The physical sensation of making a dash in my notebook: a feeling of suspension, the sound of inhaling, as much as an occular manifestation called, in our writing system, “dash.”

Architect Juhani Pallasmaa’s The Eyes of the Skin argues, according to Victoria Mitchell, that touch is at the basis of all senses and understanding this would help us de-privilege sight and inscription. Skin, coincidentally, is also one of the subjects of Starner’s article, but it is not his ending point; he pushes through to conclude about language: “When we try to make it our own, language, we fail. And when language does come and begins to possess us, . . . we cease to be ourselves. This is perhaps the only gift theater can give: to recognize, embody even, the disconnect between language and identity.” With an apology to the specificity of Starner’s theater and performance evidence, I wonder what would happen if I took this notion of his and replaced “theater” with “textiles”? Do textile practices give something similar?

Rather than elevating touch, or fixing my sites on language itself, I am interested in W. J. T. Mitchell’s ideas in Picture Theory and his essay “There are No Visual Media” that while words are also images, the act of seeing is dependent upon spacial arrangements, haptics. He recounts the experience of a person who gains sight and then needing to learn how to navigate a sighted world; they must re-learn space, distance. W. J. T. Mitchell also accounts for social life and power and argues for critical spectatorship: true seeing also sees what is not pictured.

In other words, seeing does not mean that we understand and it never has. Reading and writing also.

So if reinserting a regard for textile practices into the term “textuality,” according to Victoria Mitchell, can restore respect to craft traditions, to the work of women, and to making practices from those regions other than West, I suggest that a certain poetics may also do this—and Victoria Mitchell’s word “textility” seems as though it could replace “a textile poetics” very well. That textility, if understood as activiating many senses and ways of knowing simultaneously, and understood as a word practice not in service of an autonomous, sighted mind, can also “articulate subtle physical sensations between substance and surface . . .” I am not the first to come to this conclusion; but these commentaries are based on praxis: how my way of working has been influenced by practices and the poetics that result.

In 2010 I began drawing objects with two awarenesses: the more I looked the more I realized I did not see, and the more I could see with the felt shape of something in mind (a pinecone's layers appeared to be much like the shape of my thumbnail, for example), the more easily I could render it in a realistic fashion. I then began to stich those images along with words from my notebook. I thought that perhaps I had branched out into the world of textile arts and visual arts.

Yet what I am finding is that those textile and imaging practices have returned me to writing in a new way: I am now more acutely sensing writing as a space of touch, physicality, materiality, repetition. I also regard the mark of the word as visual while visuality itself is shaky, not sure, and not at all equated with verity. Textility, for me, has come to mean this: the differences between textile and text do not necessarily have to “benefit the conceptual apparatus of thought” if we regard textile as thinking, text as touch, and seeing as limited and multifarious.

A textile poetics