Stitches in excess: Embroidery as model for social thought and art

As a writer who stitches, I am particularly interested in the models for social thought and art provided by a certain textile practice: embroidery. I think it can help us think through 1) the extra-citizen or supra-citizen and, 2) art itself.

First: the extra-citizen—one who contributes to the making of a place but who may not officially belong (for example, the guest worker in the UAE) or even if citizen, whose very being is frequently under question, attack, or who must exist in negotiation with violent official forces (for example, the young black man in USAmerica in relation with the police).

Instead of expressing a desire to be “part of the weave,” embroidery, as a model for subjectivity, presents the “other” as capable of elaboration, proliferating beyond official or presumed status, working upon the surface of the cloth, piercing it with its presence in order to make something else that is not utilitarian, perhaps asking: are the benefits of full citizenship—integration into the weave, or a melt into the melting pot—really the desired outcome?

Here I think of a family joke: for about ten years my father couldn’t find his naturalization papers. He couldn’t vote in two presidential elections, if my memory is right. We laughed as his new title which was circulated around the house: “a man without a country.” Of course his newly achieved middle-class status, full employment, his whiteness and ambiguous accent, and the fact that the papers had been granted and were only missing, allowed for the joke to come with a laugh, but I wonder if this family joke displays some evanescence that is part of this “extra-citizen” subjectivity.

I am also thinking about my book LABOR, whose characters’ mix of tenured, contract, and contingent status overtake or play upon the substrate or ground weave—the institution, the archive, the curriculum, the archeological site, history—and create an altogether new structure.

“New structure.” I just wrote that, but do I believe this is possible?

I want to think through another model outside the “woven into the fabric of society” model. Something that would feel more true to me. Subjectivities that are never solely utilitarian or unattached, blended fully our fully outcast, and who does not necessarily desire interwoven inclusion.

This brings me to a discussion of art itself—and I go here because I am an artist, not a social scientist, and I also have doubts about political and activist models abilities to conceptualize something new enough.

I want to push against the idea that art and poetry are decorative, cathartic, utilitarian, or superfluous. That we must adhere to the structures of aesthetic judgment that we may inherit. Or that we tame language into sentences, clean line breaks, placing it in striated space: high legibility.

In other words, art and poetry are not only for art and poetry themselves. They are in the service of the future. What does that mean? I am still working this out for myself. And here, thanks to Bhanu Kapil’s teachings in 2010, I turn to Elizabeth Grosz’s Chaos, Territory, Art, a philosophy that links art and evolution. Grosz claims, “Art is evolutionary, in the sense that it coincides with and harnesses evolutionary accomplishments into avenues of expression that no longer have anything to do with survival. Art hijacks survival impulses and transforms them through the vagaries and intensifications posed by sexuality, deranging them into a new order, a new practice” (11).

To make her argument, Grosz uses philosophy and inter-species study. She argues that art exists in abundance in the natural world: it is not the domain of humans only. She explores Gilles Deleuze’s ideas of “sensation”—that art is an intensification of sensation—and, crucially, it is art because it “can detach itself and gain autonomy from its creator and its perceiver . . .” (7). Here is where she links art to nature. “Art and nature, art in nature, share a common structure: that of excessive and useless production—production for its own sake, production for the sake of profusion and differentiation” (9).

So rather than conceptualizing art as the domain of artists only (professionalizing and delimiting a realm of activity and outcomes) and something that centers around the history of art and the discourse of aesthetics, Grosz places art at a near the core of being—human and other than human—and futurity.

This understanding of art does not mean that it lacks disciplining, rules, framing. The subject who makes art frames experience and materials to such a degree that they no longer “belong” to the maker herself. This is a mini-creation story again and again; it’s evolution.

I believe that this view has the potential to bring into focus the expressions of workers, the everyday person, the non-artist, the good storyteller at work—subjects who fine tune their practices in order to create that which erupts in excess, produces laughter, produces small or large shockwaves of beauty, of surprise, of newness. This view releases “the worker” from a Marxist materialist conception only. The volume Workers Expressions: Beyond Accommodation and Resistance, edited by John Calagione, Doris Francis, and Daniel Nugent, and is about this; Robin D. G. Kelley’s Race Rebels: Culture, Politics, and the Black Working Class also.

With this concept of art and subjectivity in mind, I want to now move into textile spaces and embroidery as models for this thinking, making.

In a section entitled “The Technological Model,” Deleuze and Guatarri’s essay “1440: The Smooth and the Striated” describes how striated space—the woven cloth of warp and weft, the markings of longitude and latitude, the codified space of law—and smooth space—nomad space, the vector, the wander, and unregulated acts and states—oppose and therefore co-create each other. This richness of interrelation means that they provide a good model, according to Deleuze and Guattari, for abstract thinking and social relations.

What follows is a review of the technologies they refer to:

Weaving: this is an action to make striated space, with the warp being the set threads of the loom, extending out from the weaver’s body, never exceeding the width of a loom, and the weft threads shuttling across. The continual intersection of warp and weft makes a striated surface that might continue in infinite length but will always be delimited by the width of the loom.

Versus felt, an “anti-fabric” (475), a fibrous surface, strong and resilient, used for housing, clothing, armor by the Moguls, felt is made by the agitation fibers. It has no warp and weft, no grain in this sense. It is made through the “entanglement of fibers” and “(w)hat becomes entangled are the microscales of the fibers. An aggregate of intrication of this kind,” according to Deleuze and Guattari, “is in no way homogeneous: it is nevertheless smooth, and contrasts point by point with the space of fabric . . .” (475). Felt does not fray, thus making it a great fiber surface to use again and again without fear of deterioration.

A quilt made by random piecing is called a “crazy quilt;” it is unbounded, additive, vectoring space. Deleuze and Guattari call this piecing smooth space. The crazy quilt as a nomad textile.

A knit garment, made from panels the width of one needle, is striated space: one needle acting as the set width, as warp, and the second stitch moves across to create a surface of a set width.

This is different than crochet, where there is always a center, but stitches can build and grow out infinitely, and even into hyperbolic space—the Insitute for Figuring coral reef projects come to mind. So crochet is smooth space—it vectors out—it spreads—it is nomad space.

And so Deleuze and Guattari explore the technologies of weaving, crochet, knitting, and felting, but embroidery remains largely unexplored. They admit that “embroidery’s variables and constants, fixed and mobile elements, may be of extraordinary complexity” (476) and they leave it at that.

Inventorying the following embroidery practices and characteristics reveal it to be, I believe, a very generative technological model of lived space.

1. First, the precursor to embroidery: the stitch that yields a seam. By hand, the stitches are long; if made by machine, they are tight. This stitch joins two pieces of fabric in a seam, which can be turned inside out and pressed open, so flatness, and a hidden stitch, is achieved. This is the necessary way to build three-dimensional structures of garments. Embroidery begins with the same gesture. But does not necessarily link two pieces of fabric toward garment, structure, quilt. Embroidery works with one substrate or ground weave.

2. Quilting. In the case of quilting, a stitch functions in two ways: one utilitarian, and the other decorative: it is a stitch that binds the “quilt sandwich” together. And it can do so in very fanciful ways: so function and decoration are combined. The quilt front and the quilt back are equally treated by this stitching gesture that combines the utilitarian seam with embroidery's embellishment.

3. Working blind, or up from underneath. When a person embroiders, they work, exactly half of the time, in the blind, with the needle coming up from the underneath. This continual approximation of space is a training in haptics, space according to feel and without visible guidelines to follow. Embroidery goes through a surface—and comes back in order to make its mark. The unseen is necessary to the mark.

4. The edge that embroidery will make is vibrational, imprecise. This has the effect of always showing the constructedness of embroidery’s image, mark.

5. Shading can be achieved with embroidery, but always in pixilated blocks: it may be thought of as a close-up cubism; it prefigures pointilism in painting and the pixel of the digital. The digital, by name, refers back to this hand-made mark-making system.

6. Impermanence. Unlike ink or paint, which have adhesives, embroidery does not adhere to surfaces. It can always be removed.

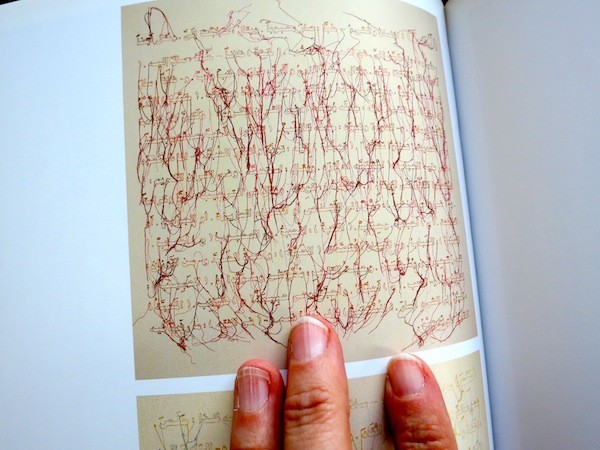

7. Embroidery is raised, sculptural. Example: the satin stitch is so named because of its creation of a satiny finish. This naming also recognizes an important aspect of embroidery thread: it plays with light and often reflects light back in ways that set it apart from the substrate. As a mark-making system, embroidery is capable of lifting up off the surface—with each stitch, it does—and with certain stitches—such as the French knot. The embroidery stitch can create quite other dimensions up and out and then they return. Here I am thinking of Ghada Amer’s work, pictured at the begining of this commentary. As with paint that drips, the threads exceed their representational use-value as mark, and like hair that continues to grow, unruly, they exceed the canvas. And so embroidery is joined to its host substrate quite firmly, but never quite permanently. It marks, alters, builds up and proliferates, but will not adhere. Like hair, like plant life, it sprouts out, insists on its presence, and may be shorn away.

The sculptural dimension of embroidery, achieved without adhesives, but through piercing and looping, is one of its most interesting features that brings us back to Deleuze and Guattari’s notion that what’s most interesting are the passages between the smooth and striated—the combinations:

I propose that embroidery occupies both smooth and striated space, or simultaneously creates both, moving between them. Released of the duty to hold any two pieces of fabric together, embroidery is a stitch that relates to its substrate in fanciful, non-utilitarian ways. It overlays smoothness onto striation. Yet it, too might generate striation: embroidery might generate word, image, narrative, and needs to adhere to the limitations of the ground weave, the substrate.

Therefore, if we see the world as one of hybrid identities, global flows, and heterotopias, embroidery provides a way to conceptualize persons whose value and identity is alternately defined and unreadable within the logics of economies and statehood; and, relatedly, embroidery is evidence for the persistence of art. The ethics of the embroidery model for subjectivity do not hinge on a progression to full citizenship, legal rights, privileges and protection: “equality,” in other words. While that might be any person’s goal, the extra-state subject whose movement is either toward citizenship or not is not ill-equipped to make beautiful elaborations on a ground weave that actually, knowingly or not, supports this.

In my last “a textile poetics” commentary, I wrote that I would like to re-write Sadie. She is the one who may or may not have tumbled down in an act of finishing: self destruction. In the text itself, I write that she is someone to revise. To re-see.

What if she rose up?

How to write the leap up off into another space—not simply the vector across. Smooth and striated space are both flat planes. What is the poetics of matter that releases, that floats off? Is this where mushrooms come in? Stationary creatures, but who release spores, whose proliferations are an end run around their stationary, affixed status? Is poetry the language that releases up into another realm? Afro-futurism comes to mind, as does Ilya Kabakov’s catapult installation which I draw from in LABOR. Can the leap from the floor keep on going up?

In Elizabeth Grosz’s discussion of architecture—the first art, she argues—she theorizes the floor: not as a bottom we are always pulled toward, but the space from which we push off and play with gravity. “The floor, ever acquiring smoothness, suppleness, and consistency, makes of the earth and of horizontality a resource for the unleashing of new and more sensations, for the exploration of the excesses of gravity and movement, the conditions for the emergence of both dance and athletics” (14).

I used to be a gymnast. But that’s another story.

Now when I stitch, embroidery hoop stretching fabric across, I think of a trampoline. A leap off with each stitch. To continue, though, the needle must come down and complete the loop. It is work between two spaces: flight and ground.

In the last paragraph of “The Smooth and the Striated,” Deleuze and Guattari propose something that I love, that has helped me live life since reading this work in 2010:

What interests us in operations of striation and smoothing are precisely the passages or combinations: how the forces at work within space continually striate it, and how in the course of its striation it develops other forces and emits new smooth spaces. Even the most striated city gives rise to smooth spaces: to live in the city as a nomad, or as a cave dweller. Movements, speed and slowness, are sometimes enough to reconstruct a smooth space. Of course, smooth spaces are not in themselves liberatory. But the struggle is changed or displaced in them, and life reconstitutes its stakes, confronts new obstacles, invents new paces, switches adversaries. Never believe that a smooth space will suffice to save us. (500)

A textile poetics