The sample book, a catalogue of influences

This grid in shades of red is from the recipe journal of the Merton Abbey dyers of England circa 1800. It is from Elena Phipps’ very useful Looking at Textiles: A Guide to Technical Terms. Textile sample books and dye recipe books are intensely beautiful objects, often stained and over-stuffed, and I believe they provide a way for me to comment on two things archeological, genealogical: the notebook, and influences.

The notebook is surely a tool for what M. C. Richards is talking about when she writes, “All the arts we practice are apprenticeship. The big art is our life.” I found this quote written on a blue card slipped into an old notebook of mine. I do not know which book of hers it came from; presumably it came from Centering, a book I have read and re-read even though I have never thrown pots on a wheel.

When I think about the notebook, Bhanu Kapil’s work as a writer and teacher comes to mind. Schizophrene begins with the act of discarding and reclaiming a notebook. And at Goddard College, I recall a class she taught where, to begin, she placed her notebook—stuffed with extra papers and with a decorated, built-up cover, as I remember it—in the center of the table. She assured us that this is where everything would begin and keep beginning, as writers. “Writing is re-writing,” she said, and we would always return to the experiment of uncovering. Writing as generating an archeology.

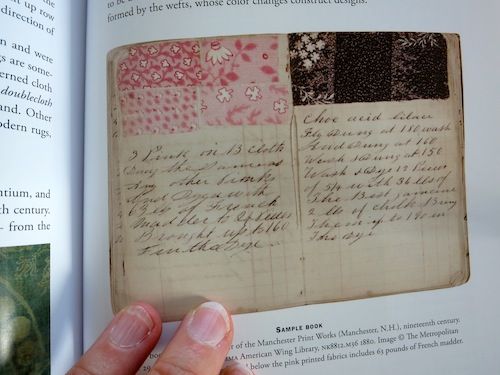

The sample book in the textile arts is a tool for memory. It is utilitarian: so that the experiment can be replicated. It becomes, to me, a beautiful object in its own right and in its objecthood, not the processes it documents which are likely shared, becomes singular and intense. It is an art book that did not set out to be an art book. It is incidental authorship. Here is another image from Looking at Textiles:

For my second commentary over this three-month span, I will create, below, a sample book page that attempts to catalogue influences and comrades in textile and text practices. This is not comprehensive. Rather, it reflects my random approach to research—a “magpie sholar” approach, as Anne Waldman calls it. Paragraph as sample-book page, an index forecasting a poetics:

I begin with Cecilia Vicuña, whose work I encountered in 2002, drew me in closer to being a poet and whose string, fabric, assemblage, text, and theory puts the line in three dimensional space. There is Rosa Alcalá and her book Undocumentaries (“...learn to be bored people--whether it's assembly work or the avant-garde.”) Victoria Mitchell’s essay “Textiles, text and techne” in The Textile Reader edited by Jessica Hemmings. Hemmings’ entire edited section on “touch.” Elizabeth Parker’s sampler. Jen Bervin and her stitched works. Kaia Sand and her stitched works. Maria Damon. Jen Hofer. Jennifer Tamayo and red thread. Ghada Amer, Joetta Maue, Jan Johnson. Elaine Showalter on piecing and writing. Rachel May on sewing and writing and the panel she convened at Naropa in October 2014, the proceedings of which are forthcoming in Naropa’s Something On Paper. Elena Berriolo’s sewn books. The silk sari weavers of Kanchipurum. The Textile Arts Center in Brooklyn and Oak Knit Studio. Johannah Rodger’s word drawings, writing as weft. Tali Weinberg and weaving, stitching, social thought and activism. Amitav Ghosh’s storyteller/weaver character. Zora Neale Hurston’s horizon as net. Small weavings the size of a page and Sheila Hicks. Indigo dyeing, gender, and Janet Hoskins’ research in Kodi. The crochet coral reef. The quilt works of Sarah Nishiura. The works of Susan Howe and Goran Sonnevi and the stutter as a textile gesture. Shopping malls, textures, architecture and Elizabeth Grosz. The tangle: mangroves, knots, and back to Vicuña’s work. Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak on the textile boycott. Sarat Maharaj on textiles and post-colonialism. Deleuze and Guattari’s smooth space and striated space, and what territory would embroidery occupy? Ikat weavings and vibration. Al Sadu weaving center in Kuwait City. Muslin as paper. Sacred books wrapped in cloth. Batik and mark-making via “resist” techniques. The veil and Anjun Alvi’s research. The gelim carpets of northern Iran. Bhanu Kapil’s “genre as quality of touch.” Gandhi and cloth. Paul Connerton and cloth and memorialization. All of my students in the last two years. Repairing my mother’s quilt.

With that ending, a poetics of textiles begins with my mother. In the year leading up to her death, I learned embroidery and I relearned to sew—something she had taught me. This female lineage is undeniable and emerges again and again in textile studies. But I did not enter textile’s domain in 2010 with craft intentions or with the desire, consciously, to connect with my mother. I had word exhaustion. I went looking for color and touch; I was tired of ink’s imprint on dry paper. Here is a page from a 2011 notebook, a kind of beginning, for me, of the notebook-as-textile-sample-book:

And from 2013, the first semester I taught a course on writing through the study of textiles, I found this, a statement that bends time—a seed for a textile poetics I am attempting to trace, to share:

“my mother already returned me to a textile”

February 5, 2015

A textile poetics