Questioning the gender of textiles

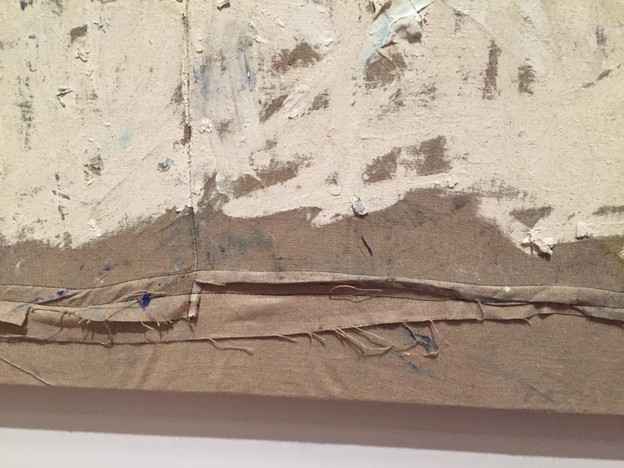

At the On Kawara show at the Guggenheim New York, at the New Museum downtown, in the MoMA’s contemporary galleries, and its “The Forever Now: Contemporary Painting in an Atemporal World” exhibit, I notice many instances of a poetics of making situated in textiles. This is exciting to notice, and it may have been there all along. It is my awareness that has changed. Pictured above, for example, is an obvious seam: a crucial sewn element in the work of contemporary painter Oscar Murillo, whose installation I will write more about in this commentary.

And yet I recoil when the didactic for Verena Dengler’s stunning installation of paintings, drawings, needlepoint, rug, and sculptural elements at the New Museum suggests “a feminist reappropriation of traditional handicrafts . . .” remembering that the amazing Claes Oldenberg show of soft sculptures a couple years back made no such “reappropriation” claim though sewing was absolutely essential to the work.

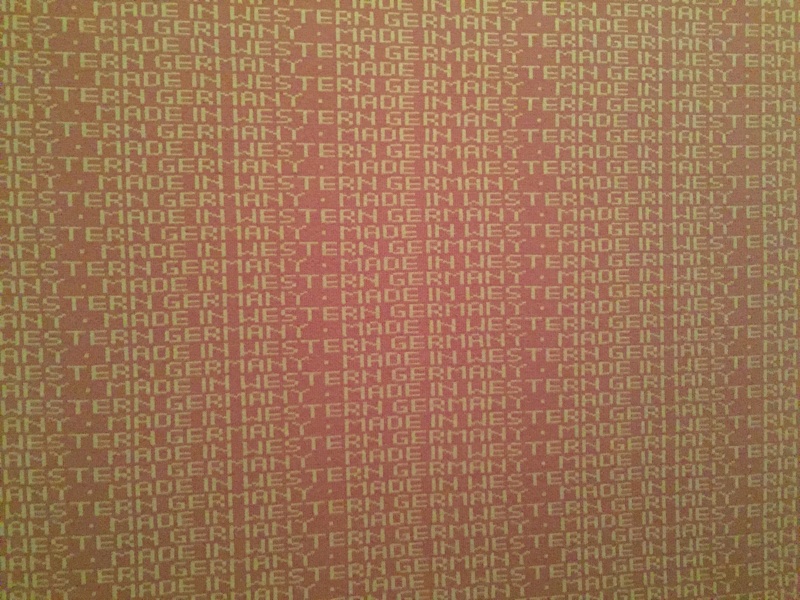

And if, according to the curators, Dengler’s pixelated images forefront the relationship between textiles and computing, then we could expect someone to comment that Cory Arcangel’s works are also a nod to textiles. My guess is that no one has. Because the gender of textile is over-determined, which means the textility of the work becomes visible primarily when a woman is working it.

Further along in my unguided gender-of-textiles tour, I stopped in front of Rosemarie Trockel’s “knit painting” at the MoMA, where the didactic states that the work is “a response to her perception of a male-dominated art world.”

Trockel is right about power, but I question whether gendering a work’s materials takes us into a particular blindness.

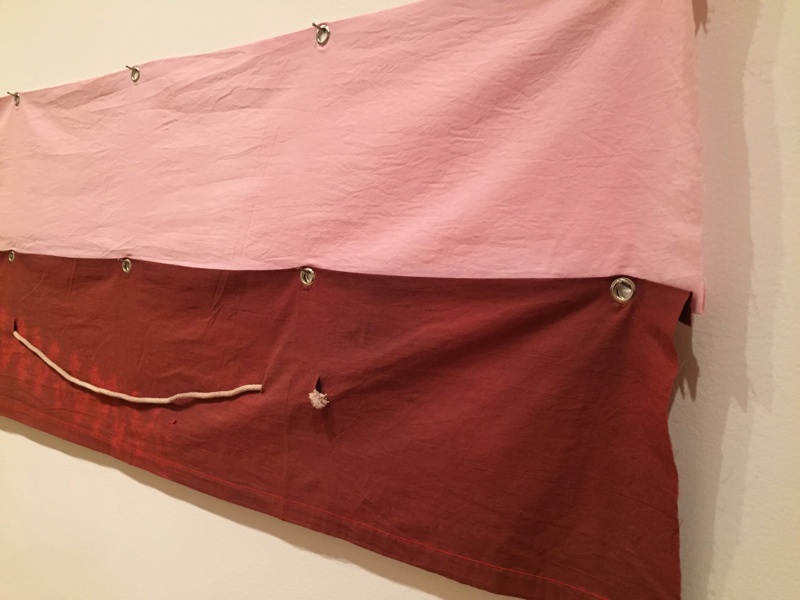

In a small room right before the exit of MoMA’s contemporary galleries, three of Richard Tuttle’s works are on display, and two of them are fabric works, with wall text articulating that his work “resist(s) easy categorization. He subjects commonplace materials such as paper, cloth, wood, and wire to a range of operations—dyeing, bending, nailing, draping, or folding” and I notice how many of those “operations” are particular to textile, yet the text does not claim that he is subverting any particularly male stereotype about materials and approaches available for his use.

If, when a male artist gestures in the textile direction, we are less able to see the textile connection, or we find it unnecessary to point out, then I think we are encountering a problem of reading “textile” through an over-gendered lens. Must the presence of textile always bring us back to a woman, a mother, a girl, a domestic practice? In visual art, is fore-fronting a textile practice always a gender commentary? I am wary of what may be an interpretive leap in this direction.

My hope: if we relinquish the urge to gender textiles, we may see textiles and a textile poetics in more works. And if we look at textile practices around the globe, we see more men involved in their making. Most interesting, for me, would be to see the textility in so many works made by women and men and those who are neither and both.

For example, I see the matrices of dates in On Kawara’s works as a weaving. The artist, living a life as textual weave, an endless succession of days, listing across and down, in rows and in columns. I am also thinking of Kawara’s “I Went” series: the red line on a map as a thread; the artist threads himself through a place.

Many iconic works at the MoMA highlight the seam and stitching; I noticed how the texture of warp and weft of canvas is thrown into relief by a slight wash of paint; I saw the drape and found fabric elements in nearly a third of the works from mid-century to present; I stood in front of glowing Rothko canvases, noticing the vibration of color blocking, and I remembered reading that abstract expressionists were highly influenced by an exhibit of quilts that was staged at mid century. I have searched to find that reference, and I can’t, so maybe I am remembering incorrectly. But the enthusiastic reception of the Gee’s Bend quilts often turned on this comparison: color blocking in quilting/abstraction in painting.

In the painting show on MoMA’s upper floor, I saw Oscar Murillo’s works as textile. His paintings are a deep nod to the pieced quilt. Swirls of oil stick create handwriting gestures across these pieced works, sometimes over the seams, perhaps signifying on the stitch that holds the quilt sandwich together, the stitch that can leap across the seam in fanciful ways. Murillo’s work features stretched canvases as well as un-stretched canvases on the floor, and the didactic instructs viewers to pick these un-stretched canvases up and inspect and arrange at will. And so the tactile enters the work—another attribute of textile.

But what is the implication of this discussion, if any, for poetry now?

In my next commentary, I will attempt to carry over some thoughts from this commentary toward gender, power, and poetry. For a long time I have not been satisfied fully embracing “écriture féminine” or letting it go. Can the idea of “textility,” coming in from many regions, many genders, open up the idea of gender and writing into a less determined, yet power and difference-aware place?

A textile poetics