'What would I want to do? Hide myself?'

Aaron Shurin's life testament to poetry

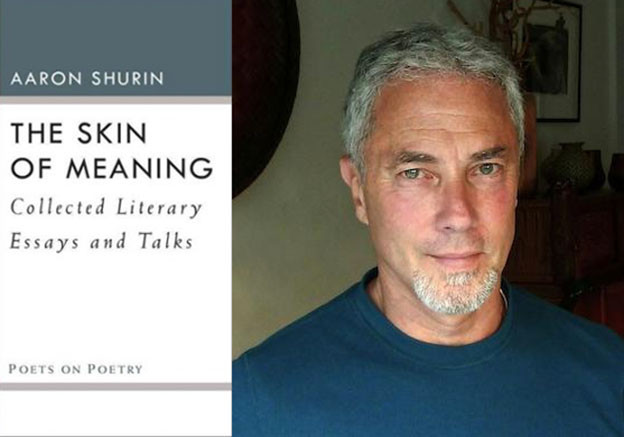

The Skin of Meaning: Collected Literary Essays and Talks

The Skin of Meaning: Collected Literary Essays and Talks

“The impulse is toward discovery of meaning, including the discovery of oneself,” Aaron Shurin explains when asked in an interview with Lily Iona MacKenzie about his comfort including personal details while writing his memoir collection King of Shadows. He continues, “So there is no act that shame will try to cover — and this is very much under the tutelage of [Robert] Duncan. There is no shame. There is just experience.”[1] Shurin’s statement captures a central aspect of his writing: an openness to expository voyages where there is no guide and there are no rules over content other than an elegant adherence to the rules of rhetoric. His prose style displays a level of decorum that the grammarians of yesteryear would praise. Writing provides Shurin the definitive lens through which to articulate concerns central to him as a lover of language, and he refuses to be less than absolutely forthright when utilizing its wares. He’s continually testifying to and probing the mysterious nature of this relationship so central to his life as a poet, a professor, and ever a student-at-study amidst its many wonders. The immaculately rendered pieces in his new collection, The Skin of Meaning: Collected Literary Essays and Talks, share the varied manifestations of his thought over the years while consumed by the thrall of his poetic predecessors.

Shurin wields a creative imagination that is consummately critical. That is, his criticism arrives steeped in an imaginative gloss deeply engaged with the subject at hand. Every piece of writing by Shurin begins and ends bounded within intimacy. Committed to a passionate presentation, his critical assessments arrive regularly embedded within emotional entanglement. With “a lust to possess and be possessed by language” (xi) his expository style fittingly recognizes no distinction between the intellect and the heart; the two are imperceptibly merged. Often he places himself at the center of the work, discovering his way forward while the writing moves along. As he remarks, “If I knew myself well I probably wouldn’t write, but I’m a sleeper. I’m drawn to writing poetry to keep me awake” (24). While this leads him to important discoveries, the presentation is never grossly confessional in nature. Self-aggrandizement is not Shurin’s game.

An out gay man since his youth, when it comes to gender and sexuality Shurin’s work is impressively forward-looking, unpacking and giving voice — in essays written decades ago — to issues that are only now reaching a wider audience. His writings seek out the opportunity to impact larger conversations happening (or not) at the wider cultural level. His goal is to impact future discourse concerning the individual and society as mediated via language. He does so while drawing from his own experience yet without becoming mired down in any autobiographical reflection. Even when confronting matters closest to his own life and writing practice, his observations provide an analytical perspective that lays out his argument in the clearest of possible terms:

At the merest level of reportage, gender signification has an overbearing and potentially warping power — as any homosexual writer knows who has had to brave, or cow to, social opprobrium against same-sex love. The switching of pronouns to fit social erotic convention is powerfully indicative of both an awareness of the tyranny of gender and the mutability of identity. (19)

And in a later essay, he further expounds upon his attraction to writing’s capacity for utilizing language to bring about societal change:

There’s a potential for social activism within the parameters of writing itself that interests me, interior to the text, interior to the sentence; one that attacks the authoritarianism of syntax and tense, of pronouns and subject identity — those sites of gender control, linear thinking, dominance hierarchies, and social ideology. (55)

Any text is first of all a body, an experience into which the reader passes by way of reading. And just as with any personal relationship, interaction with a text will leave one changed. Shurin takes a firm hold upon this exchange, acknowledging: “to awaken attention in the reader is to construct responsibility — the ability to respond, a primary requirement for social change” (56). This leads him in part towards appreciation of writing that’s richly complicated in form and execution: “A writing, then, of enmeshed simultaneities, which gives sufficient weight to its constituent presences so that they verge upon each other” (12). Shurin proves himself a thoroughly skillful interrogator of the textual in a manner that remains elementally ever physical. Nothing is presented as an abstraction removed from the lived experience that originally generated his impulse to write.

San Francisco has long been Shurin’s adopted hometown. His work often takes the form of a love letter to the city and its rampant radical literary and queer culture. AIDS, historically speaking, is regrettably its much unwelcome epidemic centerpiece. A large middle chunk of The Skin of Meaning is thus fittingly given over to selections from Shurin’s Unbound: A Book of AIDS. Not surprisingly, Shurin writes of friends lost during the tragic era in which he witnessed a generation disappear with the same mixture of engaged imagination, heart, and intellect as is found elsewhere here when he’s discussing the creative process or covering publications by his poetic peers. As a result, the Unbound essays do not in the least way stand apart from the rest of the book. Once again, it is his dedication to never turn away from any experience that shines through. He vividly recounts the effects of so many losses on the streets where he continues to live.

The ghosts who walk in my city (my ghostly city) are cast as vividly as any childhood stored in a dipped madeleine — with that fleeting precision memory affords, and the rubbed-out edges it requires. And they rise just as suddenly. But their appearances are oddly interdependent, communal. They haunt bodies rather than places. Born as adults in affectional mutuality — exchanged caresses and comradely struggles — my reappeared friends remain so framed, and show their faces by traversing planes of living faces: faces overlaying faces. Their anxious, drifting outlines cross and merge with passing strangers — strangers filled with similar resonating passions, and hungers large enough to invite in, whole, another’s presence. They flash and seize. (99)

When on the next page he bluntly states, “I am haunted,” there’s no questioning it; it’s a chilling testimonial.

Unlike many of his contemporaries Shurin has never bothered with courting any set scene or group of writers. Although over the years he’s drifted alongside some fellow travelers of New Narrative, participating somewhat in their reactionary mix of affiliation/critique towards the Language group, his writings are consistently his own stylistically and devoid of bitter attack or overt declaration of allegiance. He’s been healthily driven to write by his own inner needs. It’s only in his participation in both sides of the mentoring/teaching divide that Shurin’s closest ties with other poets are found. The intimacy of his approach to his work has been a natural benefit to him as teacher, much as it benefitted him when as student he himself experienced warm and close relationships with two early teachers.

As an undergraduate Shurin came under the close tutelage of Denise Levertov, although he later drifted away somewhat (but always felt close to her) when he met, befriended, and studied poetics under Robert Duncan as a graduate student at New College of California. In “The People’s P****: A Dialectical Tale” — his discussion of the fraught friendship between his two mentors as traced via their own correspondence — he declares himself their “lovechild” (156) and is adamant that “the poetics of their contention is dialectically in me. I’ve only ever counted such dual inheritance as one of extraordinary luck: their immediate graces mine to learn from, their tensions played out in the parameters of my work” (160). Shurin would no doubt appreciate a similar dynamic between his own work and that of his students.

Now a professor emeritus at the University of San Francisco, Shurin is responsible for shaping and directing what was once — to my personal recollection anyway — a one-year professional writing MA program into a robust two-and-a-half year MFA program. During his dozens of years teaching at USF he mentored many a struggling student. His typical approach, in part, is seen in his “Note to a Student.” “Dear Anne,” he opens with chatty warmth before drilling down in the second paragraph, “Basically, it’s become clear to me that you’re just too smart for your poetry” (50). He ends with the encouraging nod that she has “to follow” where the poem is headed because “if you can stay still, and calm your mind into a light stupidity, you can catch the poem passing like some streaming soul on its way to incarnation” (51). As a teacher Shurin appears nurturing yet steady in pointing out where students need be wary of possible deficits. Always warm, he guides his students along the path of the poetics he inherited from the pair of accomplished poet-mentors who inducted him into an ongoing tradition.

When studying poetics at New College Shurin was immersed — as everyone involved in the program was, whether student or faculty — in the practice of “a writing from reading poetics” (147) which was central to Duncan’s beliefs. This is in part an idealized vision of the manner in which one’s writing is driven by, and is the complement of, one’s reading. It is joined with the belief that there is one Great Work to which everyone contributes, borrowing and sampling, echoing variations of those who’ve come before and those yet to arrive. The Skin of Meaning represents in part Shurin’s devotion to this poetics tradition, his own contribution to a substantial section of this Great Work. There’s no doubt Duncan is at the table with fellow eternal poets and thinkers from history warmly smiling, pleased with the latest company.

1. Aaron Shurin,“Inhabiting Both Sides: Aaron Shurin’s Correspondences,” interview with Lily Iona MacKenzie, in The Skin of Meaning (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2016), 176.