'Liberation in time of emergency'

On the poetics of Duncan and O'Hara

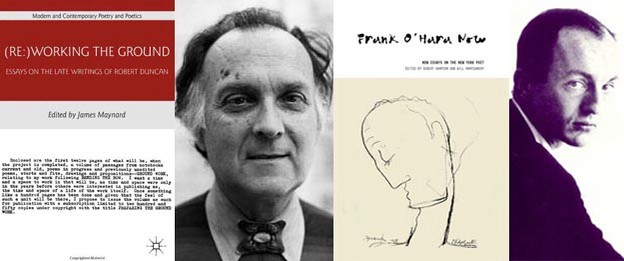

(Re:)Working the Ground: Essays on the Late Writings of Robert Duncan

(Re:)Working the Ground: Essays on the Late Writings of Robert Duncan

Frank O’Hara Now: New Essays on the New York Poet

Frank O’Hara Now: New Essays on the New York Poet

Most welcome and necessary are these two collections of new essays on the poetry of Robert Duncan and Frank O’Hara, respectively. Poets of literary imagination of the first rank, each has contributed divergent but complimentary perspectives to American poetry of the latter half of the twentieth century. Ezra Pound is daddy to them as much as Gertrude Stein is momma. Play, mirth, and wit with plenty of informal as well as formal reading and study inform the gridwork anchoring the poems and lives of these poets. They live according to the life of the poem that is in them, firmly refusing to have any sense of their art as separate from the rest of their daily affairs. In this, these two serve as models beyond compare.

Both poets share in common an open homosexuality, at odds with society of their time, that is central to their identity, along with a predilection for surrounding themselves with visual artists: O’Hara wrote art criticism, worked at MOMA, and modeled for painter friends, the likes of Larry Rivers and Grace Hartigan; Duncan settled into setting up a household with his life partner, artist Jess Collins in San Francisco, which lasted until Duncan’s passing in 1988 and during which time together they befriended several San Francisco artists from Wallace Berman’s Semina group to the filmmaker Stan Brahkage, who lived with them for a time in his youth. Each was politically committed in his own fashion, within the poetry world (the infamous feuds between Duncan/Jess and Jack Spicer, later his defense of Zukofsky against Barrett Watten; O’Hara’s social-poetic juxtaposition reading “Poem ‘Lana Turner has collapsed” while sharing the stage with Robert Lowell) as well as the public domain, taking firm stances against the oppressive gloom of the 1950s racial and sexual mores (Duncan’s groundbreaking essay “The Homosexual in Society,” O’Hara’s strident friendship with LeRoi Jones/Amiri Baraka).

Yet each poet remains distinguishable from the other, most notably by way of how personality manifests itself in the work, a matter of style and taste. O’Hara is very much the singular poet of Manhattan and all the protoplasmic buzz of activity that’s to be found there, while San Francisco with that ever-vibrant West Coast ethos is indelibly tied to Duncan’s poetic mythos. O’Hara’s poems are fast, full of witty remarks, quick moving, and in the world in which he is living. Current events are abundant, both personal and public. Duncan’s poems are shrouded in a projection of his own life’s reading, deeply otherworldly while ever pursuing profoundly mystical insight. Events occurring within the poems are timeless as he weaves references from ancient lore on up through the entire Western tradition of thought into a seamless blanketed cape of his own uniquely startling vision. The discussion of the poetry behind these charismatic figures will be long-lasting and not likely exhaustible any time soon.

While the great wealth of critical material readily available on O’Hara is continually expanding, rarely does the writing measure up to what’s on hand in this collection, superbly gathered by Robert Hampson and Will Montgomery. All the essays are exemplarily readable and nearly as entertaining reading as O’Hara’s work itself, making the book tremendously rewarding and quite the surprise. Hampson and Montgomery note that “the O’Hara that is quite so widely known and loved is often not quite the same O’Hara that we, in our separate ways, have loved” (3). They set out looking “to suggest that O’Hara is not as easily assimilable — or indeed as friendly — as he might appear” (4). There should be no doubt that they do indeed succeed in achieving this goal. As they point out, O’Hara’s “poems can be difficult and recalcitrant, their surface fluency concealing obdurate lacunae and hesitation. O’Hara’s cheerfulness is the cheerfulness of one who has encountered and embraced suffering. The ready wit conceals doubt and uncertainties” (4). And one essential component of their success in presenting a fresher, broader view of the poet is contained in their “desire to produce a response to O’Hara that had a transatlantic dimension” so when seeking contributions they drew in “established and emerging voices from both sides of the Atlantic,” resisting any easy slide into formulaic flack (5). It is not overstating the case to declare this collection an indispensable contribution to O’Hara studies.

For each subsequent generation of poets O’Hara’s work consistently proves an energizing force, fertile ground over and over again for sparking lively poems derived from reading his own, the best of which resist being wholly imitative. O’Hara is often cast as “Frank” in such work as if he’s readily around, a pal these poets might be meeting for a commiserating drink during a rough patch, personal and poetic. Reading these essays leaves the feeling that the writer approaches writing on O’Hara as if the essay-form might allow itself to be a poem. I’m not saying these essays are in any way hybrid or otherwise experimental in form, but the overall charge that is felt, the vibe as leaps in connections are made and the abundant quotes of O’Hara and others in relation to him pour forth, unleashes a steady thrill that long outlasts first reading.

David Herd’s “Stepping out with O’Hara” centers around the demonstration “that in O’Hara’s poetry he allows his thought to settle around the gesture of the step” (71). Much as mentioned above, his poems are occasions full of such charge that the reader feels as if they’re out for a stroll with the poet himself. As Herd says, “one quite readily finds oneself thinking about the way he places his feet” and “one thinks about it because he [O’Hara] thinks about it” (71). O’Hara’s projected presence is so near viscerally manifest within his poems. It is not surprising that when speaking of O’Hara’s “Poem [light clarity avocado salad in the morning]” Josh Robinson offers up a reading of “O’Hara’s Poetics of Breath” wagering that in an O’Hara poem “breath is presented as essential to cognition, which is itself something almost immediate, a bodily state of being” and “the speaker presents an intense degree of familiarity not with the absent addressee but rather with his own body: ‘and all thoughts disappear in a strange quiet excitement / I am sure of nothing but this, intensified by breathing’” (153). Adding to Herd’s comments on O’Hara’s “step,” Rod Mengham notes how “In O’Hara, the poet-as-walker and his reveries are equally mobile. In fact, the later poet maintains an equilibrium between the claims of the virtual and the real” (55).

O’Hara enjoyed having a body and celebrating its occupation of space. The preponderance of instances of his likeness being conveyed in artworks by friends and associates, and which he no doubt took much pleasure in, mirrors the prevalent physicality of presence within his writing. As Redell Olsen’s essay focusing on O’Hara and the painter Grace Hartigan reminds us, “O’Hara is similarly noted for his collaborative self-staging through both photography and art. The artists Jane Freilicher, Nell Blane, Larry Rivers, Grace Hartigan, Phillip Guston, Alez Katz, and Fairfield Porter all painted portraits of O’Hara” (188). Reading O’Hara’s poems the references to his body are inescapable, as are those to artist friends who convey its image in numerous works of art. There’s no commentary possible which refuses to acknowledge the actions of O’Hara’s busy social life amongst artists. As John Wilkinson comments, in “O’Hara’s Odes works of art are presented and become present as at once marmoreal and pulsing, exact, mobile, and sexual — and this is true of the Odes themselves” (104). He continues arguing that the Odes “work within a Romantic project, and a secular one: the confusion of unborn, living, dead and undead, and the unbinding of tenses” (105). Wilkinson sees the odes demonstrative of O’Hara’s poems as physical manifestations that exist in the instant: “The artwork lives and dies only in encounter” (105).

Undeniably it is in the encounter that O’Hara thrives. A humming electiveness that in Nick Selby’s consideration of memorial artworks to O’Hara by Jasper Johns and Joe Brainard shows itself in

the pressure of such a reimagining of the poet’s body that we have seen in relation to the work of Joe Brainard and Jasper Johns that is, I want to argue, absolutely critical to the power and affectivity of “In Memory of My Feelings.” By continually renegotiating its relationship to the poet’s actual body this is a poem that courts ambiguity, and juxtaposition, in order to discover the poetic possibilities of living as variously as possible. The closing lines of the poem resonate powerfully because of their ability to demonstrate feelingly how O’Hara’s sense of being in the poem is subject to his exploration of a complex set of relationships between performative positions available to him as poet. While sounding sincere, authentically troubled by the sense of lost feelings and the poetic occasion that calls for their memorializing, the poem’s closing moments also announce that its nostalgia for a lost self is a mere performance, a ruse in which intimacy and feeling-ness, even the body itself, are exposed as effects of the poet’s textual negotiations:

and I have lost what is and always and everywhere

present, the scene of my selves, the occasion of these ruses,

which I myself and singly must now kill

(243)

Daniel Kane’s extensive commentary on O’Hara’s collaboration with film artist Alfred Leslie on The Last Clean Shirt probes similar territory, as O’Hara mined lines from “In Memory of My Feelings” for the subtitles he provides for the film where “film becomes poetry — or film interacts with poetry. Or poetry extends film” (174). As Kane describes: “such moves invite the spectator/reader experiencing the no-longer-autonomous work of art to ‘pay attention,’ to participate in making meaning in response to a form that no longer adheres to conventional definitions of genre” (174). It is such challenging and subversive tendencies which draw in readers ensuring there will always be an audience for O’Hara’s work. He sticks you full throttle behind the moving set-changes of the poem, revealing and concealing as the surprises keep arriving. There’s nothing quite like it.

The fast-moving flexibility in the best of these essays responds in kind to this energy embodied by O’Hara’s poems; working through the poems with the same quickness of combining careful logic with fast action, risking absurdity, perhaps, but nonetheless making connections not matched — at least in energy — by previous critics. Will Montgomery’s tackling of the comparison and relationship of O’Hara’s verse to that of avant-garde composer Morton Feldman provides an example:

Although O’Hara rejects an all-encompassing “poetics,” I think it is possible to identify an important attraction to instability in his thinking in his praise of a quasi-metaphysical “unpredictability” in Feldman. Feldman sought to let “sounds exist in themselves — not as symbols, or memories which were memories of other music to begin with.” His aim in this early work to “unfix” the formal relationships between “rhythm, pitch, dynamics” is broadly comparable to O’Hara’s rejection of a “poetics” of “form, measure, sound, yardage, placement, and ear.” Feldman too scorns metre, seeking to recover a more complex and subjective experience of temporality: “I am not a clockmaker. I am interested in getting to time in its jungle — not in the zoo.” In this last statement, Feldman is close, I think, to the formal and conceptual negations of some of O’Hara’s poems — the nihilism of “Hatred,” for example, the darkness that fringes some of the Odes, or the dizzying temporal and referential leaps of “Second Avenue” or “Biotherm.” (201)

It is high time for such fabulous reading of terrific work. Frank O’Hara Now serves its purpose and then some. These essays bring acuity combined with a strong dose of good cheer. There’s a new standard set here, not only in future critical assessment of O’Hara, but that of his contemporaries as well.

After what feels as a slight lapse of critical attention from academics as well as publishers, Robert Duncan’s work is garnering further well-deserved notice. Publication of his seminal study The H.D. Book as the first of a promised multivolume Collected Writings by University of California Press finally saw the light of day in 2011. Lisa Jarnot’s long-overdue biography appeared from the same press in 2012. There’s also a “collected interviews” promised for publication by North Atlantic Books. This is the time for celebrating the worthy contributions Duncan’s work continues to offer. An ongoing cause that (Re:)Working the Ground is in part the product of, as editor James Maynard notes: “This book began as a series of papers presented at a three-day symposium entitled ‘(Re:)Working the Ground: A Conference on the Late Writings of Robert Duncan,’ which took place in the Poetry Collection at the University at Buffalo April 20–22, 2006. This event celebrated the single-volume republication by New Directions of Ground Work: Before the War/In the Dark” (10), Duncan’s final two collections of poems published together in a singular volume. Stephen Fredman reminds us how Duncan himself established the significance of the original 1983 publication of the first of these final volumes of his poems, writing in 1972 “I do not intend to issue another collection of my work since Bending the Bow until 1983 at which time fifteen years will have passed” (59).

Although subtitled “Essays on the Late Writings of Robert Duncan” and while the focus throughout is on the poetry found in Groundwork, the majority of contributions take advantage of the quite circular nature of Duncan’s poetic practice in order to revisit earlier writings while in the process addressing the later work. The result is that unfamiliar readers are not left behind in the larger discussion. These explorative essays into Duncan’s oeuvre serve to provoke initial readings of the poems and entice a fresh generation of scholars as well as poets into their own explorations of the wonders spun in Duncan’s arcana. This is especially the case since Groundwork is not so much a life’s summation of poetic work, as The H.D. Book is a midlife’s summation of reading, but rather a realization of the work’s own being. In these later poems, Duncan is as if afloat among texts whose language comes to life adrift around him as he samples as he may. These essays assist with gaining a firm foothold amidst the swirling wonder that is Duncan’s work.

This collection notably brings to print a previously unpublished preface which at one point was intended for the original publication of Before the War. Drafted in a notebook by Duncan and left off incomplete, for those readers dedicated to as complete an understanding as possible of the weave Duncan throws across his writing, this is the cat’s meow. Reminiscent of Duncan’s reading diary style he implements in The H.D. Book, as well as previous prefaces to his earlier volumes, even left incomplete, there’s plenty here offering fresh introspection into Duncan’s practice. In this preface, Duncan recognizes O’Hara’s work as an essential resource in time of need, holding it up as essential mythic poet lore in line with Whitman as well as “Old World gods” (a lineage in which Duncan views his own work aligned).

Whitman calls for an end of the Old World gods, the thralldom of ancient bonds to the codes of what the Lord abominates or the relentless Goddess demands, and Frank O’Hara, in this a true fellow to Whitman, in my own time called again for such a Liberation in Time of Emergency.

Also printed here is a short poem, “In Passage,” which was originally intended as a preface for In the Dark. The closing line demonstrates the subtle powers shaping the exchanges between Duncan’s reading and writing, where he situates a statement of prime intent he holds to in all his work: “what I divine I come into and change” (26).

Maynard’s telling of the source for Duncan’s inspiration for the title In the Dark gives example of Duncan’s tendency to “divine” and thereby have rights to “change,” making his own claim to use whatever material serves his purposes:

[D]espite its many suggestive associations with alchemy, Norman Austin’s book Archery at the Dark of the Moon (1975), James Hillman’s The Dream and the Underworld (1979), and its appearance in several different contexts throughout these same notebooks — the phrase “in the dark” officially announced itself to Duncan from one of his favorite pulp genres: science fiction. In this case, it was the opening chapter of Andre Norton’s novel Forerunner Foray (1973), with its description of the protagonist Ziantha’s membership in an intergalactic organization of psychically gifted thieves: “She was part of an organization that operated across the galaxy in a loose confederacy of shadows and underworlds. Governments might rise and fall, but the Guild remained, sometimes powerful enough to juggle the governments themselves, sometimes driven undercover to build in the dark.” Compare this passage to one of Duncan’s earlier descriptions of Ground Work: “Underground Work, the ‘new book’ might be called: not the ‘underground’ of the Revolution, but the underground of a life not in tune with the powers that rule above.” (8)

In full confirmation of this being Duncan’s source, Maynard relates in a footnote: “this exact quotation, dated March 25, [1982], appears in Notebook 66 with the note: ‘In the opening chapter of Andre Norton’s Forerunner Foray I think I have found the title of Ground Work II: ‘in the dark’” (13n29). For Duncan the separation of literature into distinction of genres, some considered more literary than others, bears little merit when it comes to what’s fuel for furthering his own writings. He pulls from all over as needed, and as come upon. At times, as seen above, readings of a later date might lead to alteration and expansion upon an earlier idea or thought in writing. Nothing for Duncan is textually static, but rather fluid, and thus in eternal transformation as the interactions of reading and writing continually feed off each other, propelling the comprehensively combined action of which Groundwork is accumulative example.

As Eric Keenaghan picks up on, “For Duncan, poetic composition is first and foremost an act of reading, which itself is the cornerstone of secular humanism” (111). A few pages further on Keenaghan continues:

Ultimately, we are readers. Our own reading praxes can be read in light of how Duncan himself would characterize that activity as an engaged participation in the process of life itself — rather than a removed position of Kantian judgment — and how he characterized reading as the means for bringing his own agency as a writer and a humanist into a productively aporetic crisis. It even produces a new kind of political engagement. (115)

Or as Robert J. Bertholf summarizes a passage from Duncan’s poem-series “The Regulators”: “The appeal is for the Muse to enter history and change the nature of our lives by altering what government regulates so that the message of the song will be present and available ‘where we wonder’” (38). Duncan expects others to continue the practice his own project takes up. At least in part, Duncan seeks to breed responsibility into his readers. There’s an urgency to respond in kind that’s welcomed and called for by the work. Duncan intends his poetry to participate ad infinitum as part of an ongoing conversation to engage with and alter the world’s imagination.

This is a conversation Devin Johnston expands on in his discussion of “Poems from the Margins of Thom Gunn’s ‘Moly’” (written during Duncan’s unanticipated immersion in an interactive reading of Thom Gunn’s “Moly,” during a long bus trip): “In terms of compositional practice, Duncan did not make firm distinctions between marginalia, inspiration, and translation: for him, all three constitute responsive or reactive dimensions of poetry. By habit and conviction, he thought that writing should arise spontaneously from reading, blurring the line between the two activities” (99). In his closing Johnston emphasizes: “for Duncan as for Gunn, poetry proposes no settled relations or certain origins but remains essentially reactive or responsive. It might include translation from one language to another or a mysterious transference of love from one person to another, according to the rhymes and resemblances that run throughout Duncan’s writing.” (107)

The looping nature of Duncan’s poems being given to reach out and draw from texts he’s reading in order to service the needs of his writing led to his referring to himself as “a derivative poet.” Stephen Collis argues this self-identification of Duncan’s is evidence of his worry over “poetry’s ‘real estate.’” Collis suggests we “see in Duncan’s use of the term a concern for the status of poetry as property. Indeed, I suggest that this was very much his increasing concern during the 1970s and his ‘slow down’ in production between 1968 and 1984. Duncan, in this reading, is revealed to be a critic of intellectual property and a defender of the poetic commons” (42). Collis distinguishes between “Duncan’s most extreme expressions of derivation and literary ‘commoning’ — his ‘emulations, imitations, reconstruals,’ et cetera of the metaphysical poets and Dante” and the “outright appropriation of found materials” claiming that “Duncan’s ‘duplications’ operate within a quasi-academic ‘citational economy,’ with the poet, in most instances, acknowledging his sources” (47). In his own work, both critical and creative, Collis pursues the use of just such means to reach active results of which Duncan would no doubt approve.

There’s a new wealth of interest in writing on Duncan by poet-scholars such as Collis, following in the wake of figures such as Nathaniel Mackey and Lisa Jarnot. This work continues to yield a bevy of potential readings for the future which prove Duncan’s weighty presence remains quite lively. Duncan’s hands, as it were, are alive in the vivid influence he plays in such writing, much as they are in his own. So it is that Peter O’Leary’s unpacking of the appropriation of angelology in “Duncan’s Celestial Hierarchy” rightly gives fair warning that “Duncan’s approach to these angelic powers is predatory — but the ‘gnostic’ invasion he imagines stains his later work not as a form of knowledge but as one of disease” (140); but as he points out, “the pleasure of these poems doesn’t come from solving them or answering them but from reading them” (133). Readers infected, as O’Leary argues, by Duncan’s “disease” suffer in delight. As Duncan writes in the poem intended but not included as preface of In the Dark, “in time you must terrify” (26). This directive is to: the poem, the poet, as well as the reader of the poem; all three after all are in some sense the same. Accepting Duncan’s terms on the level he literally did himself, i.e. life or death, no joke; it should come as no surprise if we do “terrify” ourselves on occasion. These are times without solace.

Duncan’s work demands of readers, as it should, as total an embrace as he himself gives. His willingness to release hold when writing, no clinging “to the self,” is reflected in Brian M. Reed’s study of correlations between Duncan’s work and that of Gertrude Stein. Duncan, “like Stein in the late 1920s, more narrowly inquires into the act of composition and corollary problems of identity and representation. He works from the premise that ‘ideas’ and ‘the self’ are not independent entities that an author can mirror in a poem. Instead, they come into being in the very process of ‘writing writing’” (173). Writing is never an activity Duncan takes lightly. He seeks a universal depth transcending present realities in his role of poet-as-assembler. Working on the poems in Groundwork his sense of purpose only intensified. As Clément Oudart quotes from a letter Duncan writes to his friend, Australian poet Chris Edwards:

With a note of urgency in his remark, Duncan pointed out that besides an essential ‘kindred strain … the art needs too the foundational — to address the ‘ground’ — and the declaration and carrying through of an architecture.’ Duncan’s constant grappling with the origin of creation (poiesis) — his perpetual attempt to find, found, and sound the ground(s) of his restless poetic practice — is embedded in his (at times abyssal) grounding in intertextuality. (151)

Readers should not to be turned off by Duncan’s intensive realignment of sources but rather recognize the openly inviting greeting in his wanton collaging of texts that is his intention. Dennis Tedlock relates hearing from Robert Bertholf how “when [Duncan] took a notebook with him somewhere, he often left it behind, which is why he was careful to write ‘Return to Robert Duncan’ and his street address on the first page of each notebook” (201–2). A trick to up the ante on the writing the notebook contains or a sign of willingness to have the writing be freed of ownership? I myself know poet friends who would be inclined to use such a trick to compel a soft edginess into their current manuscripts; intentionally introducing the threat that their handwritten drafts of poems might be found in the hands of indiscriminate strangers. A threat which while perhaps minor is nonetheless real all the same: even imaginary, such a threat might swell a manuscript with force that would otherwise be absent. While impossible to fully ascertain Duncan’s intention behind the practice it is clear he relished the freedom provided by so relinquishing his personal ownership of writing.

For Duncan, as with O’Hara, poems are fleeting and ethereal yet sustained as acts; grounded byways where the dedication of the poet’s life to the writing is clearly unveiled. The work holds an imbued hue which clings to the world long after the poet’s own physical presence has departed. The poems are too of this world to ever remain long gone from out it. The daily activity the poetry proves propels it into our lives easy as air and hard as stone. The poems represent the rarest of happenings, elevated beyond any transcendent feeling by the matter-of-fact occurrences of their making. In The Maximus Poems Charles Olson declares “I believe in religion, not magic or science / I believe in both man and society as religious.” Reading Duncan and O’Hara we approach an understanding of Olson’s terms not limited by parochial concerns of current political debate or filtered through academic acerbity. Caught up in the vast breach of our mundane separation from things; when it is things themselves we most long to have and hold. We’re thrown off guard, surprised that poetry might so deeply embrace gossip on one hand, as with O’Hara, yet also clamber after the counter-draw found in Duncan’s enchantments which reach roots of the imaginative core of our being. Yet it is with both our identities enjoin, reveling in the heady pleasure of bearing witness to lasting realities so gracing the page.