An antagonistic paraphernalium

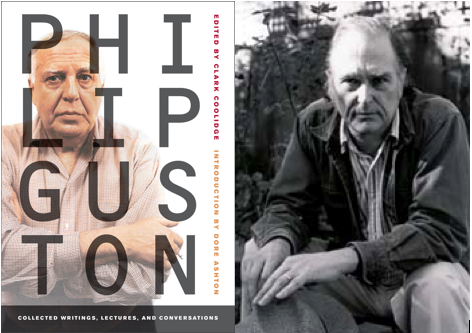

A review of 'Philip Guston: Collected Writings, Lectures, and Conversations'

Philip Guston: Collected Writings, Lectures, and Conversations

Philip Guston: Collected Writings, Lectures, and Conversations

An antagonistic paraphernalium? The answer this time is to only walk these boards. As if that line were true to all possible picture. And above it, you at the last landing, but sideways in a clear structure of junctures, some standing. I’d have first to light my head. Then the stairway. Put out a ring. Throw fingers. Alarm the enclosure of panthers left out. […] When time for a dawn I sat and watched the walls come back. He said, Look, they’re still up. Now we can leave them. Now that the backside has joined its reverse in this place. And then even an ocean, and you’ll see it’s orange. Ponder is your thought then, between the raised stumps. — Clark Coolidge

What I know I know I almost never use. — Ted Berrigan

What happens is what happens when you put the paint down. — Philip Guston

Philip Guston speaks much like he paints. Invariably, whatever is on his mind to be said will be said. A dogged will to verbally expand upon his thoughts as they are forming, drawing out his own interests against those of questioners he often views more as inquisitors drives his conversational style. As he describes the act of painting, “You’re not making a painting. That’s assumed. What are you doing? You’re searching. And finding. And leaving. And searching and finding and leaving” (Guston, 115). Editor Clark Coolidge states in his preface that “Guston was a talker” (ix). During occasions of such talks as are gathered here, Guston is frequently found “finding and leaving” the subject of the conversation at any given moment as he chooses, where and when it suits him. In the role of artist on public display, basking in his own enamored glow, Guston shines like too few. He is a happy egoist and the role suits him. As Dore Ashton describes in her introduction, Guston’s “amusing feints and dodges when confronted with obtuse questioners, his wondrous bursts of language when he felt inspired, his sometimes playful contrariness, his satisfaction in being a provocateur, and his consistent preoccupation with serious aesthetic questions throughout his working life as a painter” are all on heightened display, making for terrific reading which completely entertains while offering a glimpse of the painter as an educationally eye-opening entertainer as well (Guston, 1).

Enjoying the barrage of Guston’s wit and conversational sparring requires little prior familiarity with his work itself. The handful of reproductions — which are included, from the various manifestations of “style” Guston moves through — provide enough contextualization to keep the unfamiliar reader visually informed while at the same time hopefully encouraging the searching out of further primary evidence. Tellingly, that is what painting is for Guston: evidence. The leftover bits of an act committed, as in a crime scene. A painting is such proof of life, as Guston views it: “the canvas is a court where the artist is prosecutor, defendant, jury, and judge” (53). After Guston has moved on from working on a painting, he would have it, in addition to whatever else, possess an ongoing presence of energy exerted, “what is seen and called the picture is what remains — an evidence” (10).

Guston understands the painter to be the definitive subject of his or her own work: “There isn’t much I can say about the tendency to paint myself. I’ve always thought this characteristic to be natural in a painter” (9). This remark was first published in Art News accompanying his Self-Portrait, 1944 which does not in fact bear much of a resemblance to any photographs of Guston. As Guston moves on and his work changes, drifting away from figuration while continuing to evolve into abstract expression and beyond, so likewise do his statements regarding his art. By 1960, in an interview with David Sylvester, his antagonism over what to paint becomes the center of his concerns, “I think a painter has two choices: he paints the world or himself” (Guston, 25). This remains a visceral challenge for Guston, an ever-intensifying quandary, as it is his “hope sometime to get to the point where I’ll have the courage to paint my face. But it is very confusing because sometimes that is what I am doing, in a more total way” (26).

In the 1950s, while working within the parameters of a recognizable abstract expressionism, Guston allows that he feels some elements of figuration do hold sway in his painting. Finally in his later work it is possible for objects to clearly begin emerging.

Six or seven years ago I began painting single objects that were around me. I read, so I painted books, lots of books. I must have painted almost a hundred paintings of books. It’s such a simple object, you know, a book. An open book, a couple of books, one book on top of another book. It’s what’s around you. (276)

The intensity of Guston’s pursuit is total as he seeks to achieve the means to paint the images he feels compelled towards. Guston continually approaches the brink of the ineffable, or the “enigma” (Guston 186–90). To have located it in a painting provides a momentary reprieve of the malaise which enshrouds him and is what makes for a painting worth keeping in his eyes. Instead of showing any signs of weakening as he ages, he continues looking to achieve what he doesn’t fully understand, that state of a thing’s existence free of its creator: “The only morality in painting revolves around the moment when you are permitted to ‘see’ and the painting takes over” (29). The object itself holds its own ground, self-defining.

At points Guston’s dominant personal philosophy towards art appears rather existentialist and doomed to solipsism in outlook, yet he refuses allow himself to be so egomaniacal as to not be wary of his own tendencies towards seeing art as an all or nothing enterprise.

I don’t glory in my compulsiveness. A painter must be compulsive to paint. No one is forcing you to do it. An artist is driven to be free. I think it’s the devil’s work. You know damn well you’re dealing with “forces.” It’s hubris. We’re not supposed to meddle with the forces — God takes care of that. (307)

Guston’s friendships with other artists and writers are integral to his approach towards understanding art itself. As he says of his friendship with John Cage and the composer Morton Feldman, “in the fifties we were a kind of trio. I met Feldman through Cage” (77). Attesting how important it is to have that “one you can talk to” (78). The act of art may remain an individually arrived at moment but the exchange which only happens between such other trusted ones, even when at times it is adversarial, offers the opportunity for surprising revelation. Among the many highlights included in this gathering is an instance of roving banter between Guston and Feldman which contains many grounding moments as they square off.

MF: Do you feel the miracle comes from the language?

PG: In terms of painting, you mean, the medium, the idiom of painting?

MF: Yeah.

PG: Alone? No, there’s no such thing as painting or drawing. I mean, if you’re in a certain state of shrinkage inside, then nothing will happen, you can’t make a line. Like Pascal said, a trifle makes us happy, deliciously happy, and a trifle makes us want to commit suicide. It’s the same way in creation. I mean, an inch of a shift and there’s everything to draw. You know, everybody experiences that. So what is the medium? There is no medium.

MF: There is no medium. But …

PG: But you. You’re the medium. (83)

Familiar repartee of this sort not only benefits Guston’s ability to articulate his own concerns but also shows how much he enjoys himself in conversation.

Poets are endemic to discussions of Guston. His own references are often quite literary: “Once, when someone asked me who I studied with, I told them I studied with Dostoevesky, Kiekegaaard. I studied with Kafka. When you read a man you have contact with his mind. I’ve always liked to be in a company, as much as I could be, of writers, critical writers” (75). Among his numerous friends are poets such as Clark Coolidge and Bill Berkson, who each take a turn as interviewer in this collection, as well as seemingly dissimilar poets as William Corbett or Stanley Kunitz. Poet Alice Notley remembers meeting Guston and how “he was very present and big and attentive. I became very conscious of how much space I took up as a body, how I stood, what I was wearing” (Alice Notley, “A Poet’s Tribute,” The World no. 41 (November 1984): 4–6). Guston immediately became for Notley a physical as well as mental and imaginative force; she continues to describe him as “another of those people who made me feel full stature, not diminished not under probation for any reason. Someone who would permit me to be a poet” (4). It is as if an element latent from within her own imagination has arisen and manifested itself as a real thing in her world, a furthering of potentiality within herself which she has been expecting and welcomes. Guston lives art and his words reek of it.

Reading these talks, it becomes clear that Guston desires his paintings enact a potentiality of their own as objects, a “living” world which is in fact a near to impossible situation. His descriptions border on realms of fantasy as he describes the paint seemingly to move to the eye; defying Newtonian physics; at times sounding as though he’s drawing upon string theory:

The ones that worked and that I kept, and by worked I mean kept on exciting me, kept on vibrating, kept on moving, were the ones where it is not just line. When it becomes a double activity. That is, when the line defines a space and the space defines the line, there you’re somewhere. (202)

As Notley describes her own personal interaction with Guston’s work, “There’s your plot and there’s their plot and they both keep changing. You again look at that picture and its plot’s changed again” (6). The painting takes on recognizable qualities which alter through time triggering changing reactions from within the viewer similar to the sympathy towards a familiar friend or family member during periods of tribulation.

For Guston, the art studio has at least the potential to be a community of created things in a state of mutual support. As he says:

I remember being very strongly aware of forms acting on each other. Putting pressure on each other, shrinking each other, blowing each other up, or pushing each other. I mean, affecting each other, as if the forms were active participants in some kind of plastic drama that was going on. I think I was aware of and strove for that. In other words, if a form or shape or a color, pattern, seemed inert to me, wasn’t acting on another form, out it would go. I felt uncomfortable with it. It wasn’t paying its way. It wasn’t doing its job in the total organism. And they’re doing all sorts of things. They’re walking, they’re holding each other up, they’re supporting each other. All sorts of situations. And I felt them to be true to my feelings at that time, in that they reflected, in a metaphorical way, human emotions. (154)

Negatively or positively, emotions such as friendship underlie the artistic activity. In this way art is a part of the natural human desire to be recognized and accepted or rejected by another much like one’s own self. This recognition binds humanity together and allows for art to have a supportive role to play in our communal bonds. As in the following anecdote about one visit to Guston’s studio Feldman shares during his conversation with Guston:

I went into his studio and there’s a whole bunch of drawings, and one particular drawing had two lines. It’s not important where they were. And Philip said to me, “It’s all rhetoric.” And I said, “What do you mean?” He said, “You see that line? And you see that line a little bit on top of it? Well, that line on top of it is talking into the ear of that bottom line, telling him its troubles. [laughter] (89)

How lucky it is to share one’s fate with somebody else. To get as far as possible beyond the isolation each of us understands all too well. More than equal to the task, Guston’s words, alongside his work, remain uniquely human in that immortal manner in which the sun and moon continue rise and fall day after day.